1-Page Summary

Because the world is increasingly dependent on technology, being competent in technical subjects like math and science is beneficial for both your career and life in general.

Some people find math and science intimidating, and Barbara Oakley, the author of A Mind for Numbers, used to be one of those people. However, she overcame her technophobia, eventually earning a doctorate degree in engineering. Her purpose in writing this book is to help you learn math and science by showing you how you learn and how to build effective study habits.

In this guide, we’ll discuss the principles that Oakley presents, often examining their scientific basis or comparing them to the ideas of other experts. We’ll begin by discussing Oakley’s exposition of how your brain works, which lays a foundation for understanding how you learn. We’ll then discuss Oakley’s strategies for remembering information and developing good habits, both keys to long-term success in learning math and science. Finally, we’ll consider how to overcome the problem of procrastination, which is a special kind of habit, and one that Oakley warns can severely hinder your academic success if it is not dealt with.

Brain Basics: How You Learn

The Two Modes of Thinking

A key theme of A Mind for Numbers is that alternating between modes of thinking can help you learn new things and problem-solve effectively. Oakley explains that your brain naturally alternates between two modes of thinking: focused and diffuse.

According to Oakley, focused-mode thinking occurs when your attention is focused on something, and it allows you to process detailed information. However, she notes that it’s susceptible to the “Einstellung effect,” which occurs when you are unable to solve a problem because the solution is outside the scope of where you are looking for it.

Oakley asserts that diffuse-mode thinking occurs when you relax your focus or let your mind wander. She explains that it continues to subconsciously process information from previous focused-mode thinking, but in a different way: It can circumvent the Einstellung effect by allowing you to mentally step away from detailed problems and see the big picture, or generate creative solutions by making connections between diverse concepts.

Thus, Oakley explains that solving any difficult problem requires an exchange of information between your brain’s focused-mode and diffuse-mode functions. She recommends that you start by deliberately focusing on the problem and then deliberately divert your attention, allowing your brain to switch to diffuse mode. Repeat as needed, alternating between modes until you solve the problem.

Comparing Perspectives on the Two Modes of Thinking

Other writers have used a variety of terms for what Oakley calls “focused-mode thinking” and “diffuse-mode thinking.”

Edward de Bono coined the terms “Lateral Thinking” and “Vertical Thinking” for what Oakley calls diffuse mode and focused mode, respectively. He emphasizes that lateral thinking (diffuse mode) generates new ideas or solutions, while vertical thinking (focused mode) down-selects between possibilities. Thus, in de Bono’s view, you should switch to diffuse mode to generate new ideas, and switch to focused mode to select and implement a solution.

Malcolm Gladwell contrasted “conscious thinking” with “unconscious thinking.” These modes of thinking can be loosely mapped to Oakley’s focused and diffuse mode thinking, respectively. Gladwell presents conscious thinking as a tool for rational decision making and unconscious thinking as a tool for intuitive decision making. He emphasizes that unconscious thinking operates quickly and that trained intuition can be highly accurate. Thus, he advocates using unconscious thinking to solve certain types of problems directly, although he doesn’t directly address the kind of academic problems that Oakley focuses on.

Daniel Kahneman wrote about “System 1” and “System 2” thinking, defining them similarly to Gladwell’s “unconscious” and “conscious” thinking modes, respectively. However, he highlighted the many types of bias that can cause intuition to be wrong to emphasize the importance of System 2 to catch System 1’s errors. As such, he seemed to assume you operate in “System 1” by default, and emphasized the need to invoke “System 2” to analyze the output of “System 1” rationally whenever the consequences of an error are significant. This theme resonates with Oakley’s observation that once you identify a possible solution with diffuse mode, you still have to switch back to focused mode to work out the details and make sure the solution actually works.

How to Switch Between Modes of Thinking

Oakley lists a number of ways you can give your diffuse mode time to operate on problems you are trying to solve:

- Go for a walk or do something athletic.

(Shortform note: This method can be doubly effective, as health psychologist Kelly McGonigal reports that during physical exercise, your muscles secrete chemicals called myokines that stimulate your brain, increasing cognitive performance and alleviating depression.)

- Take care of routine tasks, such as housework or laundry.

(Shortform note: This helps make efficient use of your time while studying, but as an added benefit, a recent study concluded housework is a feasible means for workers with sedentary jobs and limited time to get the health benefits of physical activity.)

- Get some rest. Oakley asserts that your brain cannot function normally without enough sleep.

(Shortform note: Other authors echo this assertion. Matthew Walker reports that sleep improves long-term memory of important facts while eliminating trivial information, and warns that lack of sleep impairs your ability to focus.)

The Two Types of Memory

To learn anything, you have to store it in your memory. Oakley explains that your brain has two types of memory:

- Working memory is your brain’s workspace: It holds the information that your mind is actively processing. Your working memory has limited capacity. Oakley asserts that, on average, it can only hold about four units or “chunks” of information at a time, although this varies from person to person.

(Shortform note: Not all sources agree as to exactly how many “chunks'' of information an average person’s working memory can hold. The number four comes from Cowan’s research, which was published in 2001, and largely supplanted an estimate of seven based on Miller’s work in 1956. In 2003, Gobet and Clarkson published a study revising the estimate to between two and three. In any case, your working memory can only hold a few units of information.)

- Long-term memory is your brain’s library. It stores information for future reference. According to Oakley, it can store billions of pieces of information, although information that you don’t access repeatedly may get buried under other information and become difficult to retrieve.

Diffuse Mode Memory

Oakley doesn’t fully discuss how long-term memory might relate to the two modes of thinking. Focused mode can retrieve information from long-term memory and load it into working memory where it makes use of it. Does diffuse mode operate directly on data in your long-term memory? Or does diffuse mode have its own unconscious version of working memory that absorbs information from your focused-mode working memory so diffuse mode can operate on it later?

Given Oakley’s assertion that diffuse mode eventually runs out of information to process, the second explanation seems to fit better. Furthermore, Gilchrist and Cowan have identified that there are both conscious and unconscious aspects of working memory.

Chunking: Your Brain’s File Management System

According to Oakley, as you take in information, your brain tries to assemble it such that it makes sense. This process of assembling the information into coherent concepts is called “chunking,” and the concepts it assembles are called “chunks.”

Oakley explains that, as you study, your working memory quickly fills up with information. But once your brain processes this information into a coherent chunk, it takes up only one slot in your working memory instead of all four available slots. She asserts that the more deeply chunked something is in your mind, the more intuitive it becomes.

As an example of the chunking process, think about learning to drive a stick-shift. Many small tasks go into shifting gears: You have to move the shifter to the right position, let out the clutch while keeping the engine RPMs in the right range, and so on. However, once your brain has condensed all this information into a single chunk, you can shift gears intuitively, without thinking individually about all the little tasks that go into it.

(Shortform note: Oakley describes chunking as a mental process that occurs naturally as part of the learning process. However, others have explored applications of artificial chunking. For example, in his book, Moonwalking with Einstein, Joshua Foer describes chunking as a mnemonic device: You can remember longer strings of numbers by breaking them up into groups of digits. This could be called “arbitrary chunking,” since you arbitrarily impose the grouping and artificially create a unifying meaning for each chunk of numbers.)

Remember What You Learn

Oakley explains that the more connections the chunk has, the more memorable it is, and the more often you access it, the stronger the connections become. More connections and stronger connections both make a chunk more accessible. Thus, there are two factors that determine how well a concept will stick in your memory: how memorable it is, and how often you recall it. Let’s explore strategies for making information memorable and recalling information.

Make Information More Memorable

Factors That Affect Memorability

According to Oakley, something will generally be more memorable if it possesses one or more of the following factors:

- You write it out long-hand (Writing Factor).

- You say it out loud (Speech Factor).

- It has more connections, literal or metaphorical, to other concepts (Association Factor).

- It involves moving your body (Movement Factor).

- It makes you laugh (Humor Factor).

- It tells a story or connects concepts through cause and effect (Story Factor).

- It invokes multiple senses (Sensory Factor).

- It connects visual and spatial data to form visuospatial map chunks (Spatial Factor).

Additional Memorability Factors from Joshua Foer

In Moonwalking with Einstein, Joshua Foer also identifies factors that make information more memorable. He corroborates Oakley on the sensory, humor, and spatial factors, emphasizing the importance of the spatial factor. Additionally, he includes four factors that Oakley doesn’t consider:

The information stands out as novel or unique (Novelty Factor).

You can relate the information to your own experiences (Personal Factor).

It’s concrete rather than abstract (Concreteness Factor).

It displays patterns or structure, like rhyme or repetition (Structure Factor).

Techniques for Making Information More Memorable

But what if you need to remember something that, by itself, isn’t all that memorable? As Oakley explains, you could come up with an acronym or a sentence composed of words that symbolize the ideas you need to remember. Oakley notes that if you say it out loud or set it to music and sing it, you can also take advantage of the speech and song factors.

Another technique that Oakley discusses consists of developing a “visual metaphor,” or mental image that represents what you need to remember. She also discusses the “memory palace,” which is a powerful extension of visual metaphors to take advantage of the spatial factor and potentially the story factor. As Oakley explains, you first think of a place that you know well, such as your home or college campus. Then you imagine yourself moving through the place, interacting with objects. Each object is a visual metaphor for something you need to remember.

For example, suppose you need to memorize the hierarchy of taxonomy for biology class: Kingdom>Phylum>Class>Order>Family>Genus>Species. In your mind’s eye, you are walking across campus when you suddenly bump into the King of England, who happens to be visiting your college that day (Kingdom). Next, you stop at the cafeteria, where you order a Philly steak-and-cheese sandwich (phylum). Then you go to class (class).

After class, you head back to your dorm room, but you have to take a detour because a drill sergeant is parading his troops on the campus lawn and shouting a lot of orders (order). When you arrive at your dorm room, you discover your family has come to visit (family). After your family leaves, you notice that your laundry basket is full of jeans, so you head over to the campus laundry room to wash your jeans (genus). However, in the laundry room, you discover that your jeans are covered with tiny yellow specks (species) that won’t wash off.

Foer’s Techniques for Making Information More Memorable

Unlike Oakley, Foer doesn’t discuss singing or speaking out loud as a way of making information more memorable. Perhaps this is because when you’re taking an exam and need to remember something, you’re generally not allowed to break out in song or get up and dance around the classroom.

However, Foer does discuss the use of visual metaphors and the memory palace. He explains that the term “memory palace” is a modern name, while earlier sources refer to it as the “method of loci.” In these early descriptions, each imaginary location where you place a visual metaphor was called a locus (and loci is the plural of locus).

In Foer’s description, the memory palace is the master technique to which all other methods are subservient. You populate your memory palace with visual metaphors, and in some cases, you may use symbolic sentences to generate visual metaphors for abstract concepts or develop more memorable images.

For example, if you are building a memory palace for your biology class and you want to consolidate the hierarchy of taxonomy into a single image, you could symbolize it with the sentence, “King Phillip cleaned orange fungus off Jenny’s spectacles,” where King = Kingdom, Phillip = Phylum, cleaned = class, orange = order, Jenny = genus, spectacles = species. You then place the mental image of this scene at one location in your memory palace.

Review Information to Keep it Accessible

Now, let’s discuss strategies for recalling information. Oakley cautions that even a memorable fact may soon become unretrievable if it is not reviewed. She presents some strategies you can use to make your review sessions more effective:

- Test yourself with intentional recall. If you just finished a reading assignment, Oakley recommends closing the book and trying to recall the essence of what you just read. She asserts that this is the most effective way to embed the content in your memory.

(Shortform note: William James documented that active repetition (or intentional recall) is more effective for learning than methods of passive repetition, such as rereading the material, over a hundred years ago. Numerous studies since then have confirmed this effect.)

- Oakley suggests practicing “spaced repetition,” where you repeatedly revisit material at designated intervals. She recommends revisiting any new information within one day, so you don’t forget it completely.

(Shortform note: Psychological studies have determined that students who practice intermediate spacing between study sessions tend to perform better than those who do all their studying at once, and also better than those who break it up into smaller sessions and study too frequently. Other experts assert that the optimal time for a recall session is when the information in your mind gets fuzzy—it’s no longer fresh, but it’s not gone yet either.)

Take Control of Your Habits to Make the Most of Study Time

Understand the Habit Chunk

According to Oakley, your study habits (good or bad) will have a strong impact on your ability to learn math and science. She explains that habits develop via the same chunking process that condenses information in your brain and facilitates storage in your memory. A habit chunk consists of four pieces of information:

- The Cue: Oakley identifies this as the stimulus that your brain responds to by performing the habitual action. She notes that cues can be linked to people, places, time, feelings, or events.

- The Routine: This is the action or sequence of actions that you perform when the habit is triggered by the cue.

- The Reward: Oakley asserts that you have to derive some kind of benefit from executing the routine for a habit to develop. Your brain executes the routine in response to the cue because it expects the reward. She also points out that only immediate consequences of the routine are stored as part of the habit chunk. This is why bad habits are possible: The reward is immediate but transient and the long-term consequences are negative, but the long-term consequences are not processed as part of the habit chunk, and thus do not automatically cancel out the reward.

- The Belief: According to Oakley, your habits are grounded in your perception of reality and of your own identity.

For example, suppose you make a habit of reading your text messages immediately:

- The cue is the ringtone your phone plays when you get a text.

- The routine might consist of retrieving your phone from your pocket and accessing the text-messaging app.

- The reward is the pleasure that you derive from reading text messages.

- The underlying belief could vary: Maybe you believe responding promptly to communications is an important part of being respectful toward others, or maybe you identify as a social person and believe in staying connected with others through text.

Comparing Habit Models

Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit, and James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, offer descriptions of the make-up of a habit that are similar to Oakley’s model (although both omit the “belief” element of Oakley’s model). However, BJ Fogg, author of Tiny Habits, provides an alternative model.

According to Fogg’s behavioral model, you perform an action or behavior when a prompt alerts you to the opportunity to do so, and the combination of your ability to complete that action and motivation to do so is above a certain threshold. Fogg’s model applies both to habits and to non-habitual actions.

Fogg conceives habits as self-perpetuating. The more often you do something, the better you get at doing it, so your ability to do it increases. Further, the habit reward provides motivation to keep doing it. This combination of increasing ability and increasing motivation makes a behavior more likely to exceed the threshold the next time you receive the prompt—thus making you more likely to engage in the habit again.

Strategies for Changing Habits

As Oakley explains, you can modify your habits by making changes to any part of the habit chunk:

1) Oakley suggests that you can prevent bad habits from triggering by isolating yourself from their cues. For instance, if hearing a certain song while driving triggers you to habitually speed, remove this song from your driving playlist.

(Shortform note: Clear corroborates this suggestion of Oakley’s. He proposes four “laws” of forming new habits, each with an inverse form for breaking bad habits. His first law is to make cues obvious, and inversely, to prevent bad habits from triggering by making their cues invisible.)

2) Overwrite the habit routine by changing how you react to the cue. Oakley notes that this strategy requires a deliberate plan and an exertion of willpower, but that it plays a key role in optimizing your study habits.

(Shortform note: Fogg identifies this same strategy of changing the behavior associated with a certain prompt. However, instead of highlighting the need for willpower, he advises designing the replacement behavior to take as little willpower as possible. To do this, he advises you to make the replacement behavior easier and more desirable (higher ability and motivation) than the old one.)

3) According to Oakley, sometimes you can modify the habit by manipulating the reward. If you understand what reward is tied to a certain habit, you may be able to change the reward to either reinforce or dismantle the habit. For instance, creating rewards for sticking to good habits can keep you on the right track.

(Shortform note: In Fogg’s model, rewards primarily influence motivation. He cautions you to avoid basing habit changes too much on motivation, because motivation is often complex and can be fickle. Nevertheless, he presents celebrating small victories as a key strategy for reinforcing changes that you are trying to make to your habits.)

4) Address underlying beliefs fueling the habit. Oakley asserts that to change a habit, you must believe that you can change and that the change will be an improvement.

(Shortform note: Clear observes that it is particularly easy to pick up habits from people you are close to or look up to because these people influence your beliefs. This implies that you can sometimes prompt a change in your habits by changing the company you keep and thus changing your beliefs.)

Overcome Procrastination

Understand the Procrastination Chunk

Oakley asserts that habitual procrastination is often your most significant barrier to learning math and science. She explains that procrastination is a special kind of habit, but it has the same basic components as any habit chunk:

- The Cue: According to Oakley, the procrastination cue comes in two parts. The first part is the unpleasant feeling that you get from anticipating an activity that makes you uncomfortable. The second part is the “distraction,” which is any stimulus that you can shift your focus to in order to escape the pain of anticipation.

- The Routine: Oakley explains that the procrastination chunk in your brain generally doesn’t have just one routine, but rather several sub-routines. The type of distraction that completes the cue determines which sub-routine gets triggered. For example, if the distraction is a new email from an online retailer, maybe the sub-routine consists of following the link in the email and mindlessly browsing the retailer’s website.

- The Reward: According to Oakley, the reward that allows a procrastination habit to develop is temporary relief from the pain of anticipation.

- The Belief: Oakley reiterates that one of the keys to changing any habit is believing that you can change. If you’ve been procrastinating habitually for a long time, it might be tempting to believe procrastination is an innate part of who you are, but understanding the makeup of the procrastination habit can help you change this belief.

Oakley and Eyal: Procrastination vs Distraction

Some authors discuss a process similar to Oakley’s “procrastination” using different terms. For instance, Nir Eyal uses the term “distraction” to define any behavior that draws you away from the tasks that you need to focus on to accomplish your goals. He asserts that we are all fundamentally motivated to free ourselves from discomfort, and we get distracted because distractions offer temporary relief from mental discomfort.

Furthermore, he states that distractions start with “triggers” and distinguishes between internal and external triggers. He equates internal triggers to the sense of discomfort or dissatisfaction that prompts you to look for an escape. External triggers, then, are environmental stimuli that interrupt your concentration and/or offer an opportunity for escape.

Thus, “distraction” as used by Eyal seems to be functionally synonymous with “procrastination” as used by Oakley, and Eyal’s description of the root cause of distraction is compatible with Oakley’s description of the procrastination habit model. As such, we can compare Oakley’s strategies for avoiding procrastination to Eyal’s for additional perspective. We’ll discuss both Oakley’s and Eyal’s strategies in the next section.

Strategies for Overcoming Procrastination

In addition to her general strategies for changing habits, Oakley provides strategies specifically for combating procrastination:

1) Plan your time. According to Oakley, just having a plan for how to spend your time can reduce the temptation to procrastinate, and tracking your time can help you identify specific procrastination habits. To this end, she recommends keeping a daily to-do list in a journal planner or on a conspicuous whiteboard.

(Shortform note: Eyal also identifies building the right schedule as one of the key strategies for overcoming distraction. However, he asserts that just making a to-do list of daily tasks is not enough, because it’s too easy to move uncompleted tasks to tomorrow’s list if you slip into distraction. Instead, he prescribes “timeboxing,” where you split up your entire day into blocks (or boxes) of time, all of which are allocated to specific activities. This way, if you find yourself doing anything other than what you planned to be doing at that time of the day or night, you can identify exactly when you were distracted. Eyal recommends scheduling one 20-minute box each week to reflect on the times you got distracted and consider how you could adjust your schedule to avoid such distractions in the future.)

2) Eliminate distractions. Oakley points out that avoiding distractions can prevent your procrastination sub-routines from triggering.

(Shortform note: Eyal likewise identifies “eliminating triggers'' as one of the keys to conquering distraction. He presents a list of triggers to manage, including in-person interruptions, incoming email, text, or social media media, and desktop clutter. By letting people know when you are and are not available, disabling notifications for most incoming communications, establishing set time-boxes for responding to communications, and keeping an organized desktop, Eyal says you can greatly reduce distractions.)

3) Ignore distractions. Oakley acknowledges that this requires an exertion of willpower, much like overwriting a habit routine, but she says this is a key strategy for overcoming procrastination habits. She notes that you can use meditation techniques to let distractions pass.

(Shortform note: Author Bhante Gunaratana describes “mindfulness” meditation as a state of mental awareness in which you listen to your thoughts without getting caught up in them. You just observe what’s going on in your mind, without expecting, reacting, pondering, analyzing, or passing judgment on any of it. Medical studies affirm that this meditation technique tends to reduce susceptibility to distraction. Presumably, every time you observe a distraction without responding to it, the association between the distraction and its procrastination sub-routine grows weaker.)

Shortform Introduction

Because the world is increasingly dependent on technology, being competent in technical subjects like math and science is beneficial both for your career and life in general.

You may not realize it, but your brain has an extraordinary capacity for complex calculations: Tasks like stepping over a garden hose as you walk across your lawn require tremendously complex computations, and yet they seem easy because your brain does them intuitively. Barbara Oakley wrote A Mind for Numbers to help you learn math and science well enough that they, too, become intuitive. In this book, Oakley presents principles about how your brain works and builds strategies for learning and studying upon these principles.

About the Author

Barbara Oakley is a professor of engineering at Oakland University who also teaches a MOOC (massive open online course) called “Learning How to Learn: Powerful Mental Tools to Help You Master Tough Subjects” through Coursera. To date, this class has reached over two million students.

Oakley grew up thinking she was technically inept. From childhood through her career in the US Army, she struggled with technical subjects. However, recognizing the benefits of technical competence, she determined to overcome her technophobia and eventually earned a doctorate in systems engineering.

Since 2007, Oakley has authored or co-authored numerous books and articles on the relationship between neuroscience, social behavior, and learning, including Learn Like a Pro, Mindshift, and Uncommon Sense Teaching.

Connect With the Author

The Book’s Publication

A Mind for Numbers was Oakley’s seventh book, published in July 2014 under the TarcherPerigee imprint of the Penguin Random House Network. However, it was her first book on the subject of study skills, which would become the subject of her most popular books. Significantly, it was published the month before Oakley’s online class, “Learning How to Learn,” debuted: The content of the course and the book closely parallel one another, and thus reinforce each other if taken together. That said, the book can also stand by itself.

In 2014, A Mind for Numbers ranked 14th on the New York Times’ list of best-selling science books. Based on Amazon’s best-seller rankings, it’s Oakley’s most popular book to date.

The Book’s Context

Intellectual Context

A Mind for Numbers is primarily a synthesis of established neuroscience and study techniques. It brings relevant information together and makes it actionable for students, rather than disclosing original research or new discoveries. Nevertheless, Oakley also provides original insight into the subjects that she synthesizes.

In this guide, we will briefly explore the origins of many of the concepts Oakley presents, and compare the way she develops them to the way others have used them, if applicable. For example, we’ll discuss how Oakley’s “focused-mode” and “diffuse-mode” thinking correlate to the concepts of “vertical” and “lateral” thinking proposed by Edward de Bono half a century earlier.

The Book’s Strengths and Weaknesses

Critical Reception

Most book reviewers praised A Mind for Numbers for its applicability, saying either that it helped them in their studies or that they wished they had read it when they were in school. It holds an average rating of four stars or more on platforms such as Amazon and Goodreads.

However, the book was not without its critics. Both positive and critical reviewers pointed out that A Mind for Numbers is about learning techniques that can be applied to any field of study, rather than just math and science. This led positive reviewers to praise the book for its wide applicability, while critical reviewers expressed disappointment that it did not delve into math and science more deeply.

Commentary on the Book’s Approach

Oakley’s overall approach in the book is as follows:

- First, she presents principles of neuroscience.

- Then, she builds strategies for effective studying based on these principles.

- Next, she illustrates and substantiates these strategies with examples and testimonials.

- Finally, she challenges the reader to apply these strategies with exercise questions.

Within each chapter, the principles and strategies are often interspersed with anecdotes and testimonials. This led some critical reviewers to accuse the book of being sloppy in its organization and full of tangential information that doesn’t contribute significantly to the book’s main principles or purpose.

However, it’s possible that Oakley intentionally buffered the book’s weightier content with lighter anecdotes. One of the book’s main points is the importance of alternating between focused and diffuse thinking when learning new things or solving difficult problems. Focused thinking involves focusing intently on something to understand it in detail, while diffuse thinking corresponds to a more relaxed mental state. The handoff between the two modes plays an important role in the learning process. In this light, Oakley’s organization allows the reader to alternate naturally between focused and diffuse thinking while reading the book, and thereby learn the material better.

Commentary on the Book’s Organization

One theme that Oakley stresses in A Mind for Numbers is the importance of revisiting a concept repeatedly to engrain it in your memory. Consistent with this principle, she repeatedly revisits topics throughout the book. For example, she introduces her discussion of habitual procrastination (and how to avoid it) in Chapter 5, reiterates and expands upon it in Chapter 6, moves on to other topics in Chapters 7 and 8, and then returns to the subject of procrastination again in Chapter 9.

This cyclical approach to the organization of the book has its pros and cons. On the one hand, if you read the book from front to back, the repetition ensures that you will remember the key concepts better than if you were only exposed to them once. On the other hand, the cyclical repetition can make it more difficult to find something again if you wish to refer back to it. The progression of logic might also be easier to follow if the book were more linear, and the repetition makes the book less concise.

Our Approach in This Guide

We’ve organized our discussion of the book’s material into thematic sections to aid the flow of logic and make topics easier to find. Here’s a mapping of the parts of this guide to the chapters of the book:

- Part 1 → Chapters 2, 3, 12

- Part 2 → Chapters 3, 4, 7, 14

- Part 3 → Chapters 10, 11

- Part 4 → Chapters 4, 6

- Part 5 → Chapters 5, 6

- Part 6 → Chapters 5, 6, 8, 9

- Part 7 → Chapter 17

- Part 8 → Chapters 13, 14, 15, 16, 18

To understand the study strategies that Oakley recommends, we first need to discuss how we learn and how we remember what we learn. In the first two parts, we’ll also examine how Oakley’s principles compare to Edward De Bono’s, Malcolm Gladwell’s, and Daniel Kahneman’s.

After laying this foundation, Parts 3 and 4 will discuss Oakley’s two general strategies for remembering information: making it memorable, and repeating it. We’ll also compare and contrast Oakley’s strategies to those of other learning and memory experts, such as Joshua Foer and Scott Young.

Part 5 focuses on habits, because your study habits arguably play the most significant role in your long-term success at learning math and science. We’ll compare Oakley’s model of how habits work to the models described by James Clear, Charles Duhigg, and BJ Fogg. Part 6 focuses on a special kind of habit, procrastination, which can severely hinder your academic success if you don’t deal with it.

To ensure that you can demonstrate what you’ve learned in an exam setting, it’s important to know how to manage test-taking anxiety, which is the theme of Part 7. Finally, in Part 8, we’ll discuss some of Oakley’s additional tips for achieving your full potential, such as how to get the most out of study groups and how to maximize your creativity.

To focus on the central principles of these themes while keeping this guide as concise as possible, we have largely omitted discussion of the anecdotes and testimonials that appeared in A Mind for Numbers.

Part 1: Understand How You Think

A key theme of A Mind for Numbers is that alternating between modes of thinking can help you learn new things and problem-solve effectively. To understand how to do this and why it works, you first need to understand a few things about how your brain works. In this section, we’ll first discuss your brain’s two modes of thinking. Then we’ll comment on switching between them to solve problems.

The Two Basic Modes of Thinking

Oakley explains that your brain naturally alternates between two modes of thinking: focused and diffuse.

As an analogy for these two modes of thinking, imagine a camera with a variable lens. If you zoom in on the subject, details are clearly visible, but the surroundings are cut off: This is like focused-mode thinking. If you zoom out, the big picture comes into view, but details are obscured: This is like diffuse-mode thinking.

Oakley notes that in nature, animals must alternate between detail-oriented tasks, such as eating berries off a bush (focused mode), and general awareness, such as scanning their environment for predators (diffuse mode). She suggests that this could explain the origin of the two modes.

(Shortform note: This may be an original insight on Oakley’s part. The concept of these two thinking modes was probably first recognized by Edward de Bono, but it appears he studied the modes without delving into their evolutionary origins. Other researchers have suggested that the different functions of the left and right brain hemispheres provide an evolutionary advantage for balancing general awareness with specific tasks. However, Oakley might be the first to connect this concept to the origin of the two thinking modes.)

Based on Oakley’s exposition, let’s compare the two modes in terms of when they are triggered, how they operate in your brain, why you would use them, and the limitations of each that make it necessary to use both.

Focused Mode

When: According to Oakley, focused mode thinking occurs when you focus your attention on something.

How: Focused-mode thinking is associated more with the left hemisphere of the brain than the right (although both are involved), with elevated activity in the prefrontal cortex (the part of your brain just under your forehead). Oakley explains that in focused mode, your thoughts progress rapidly along short pathways between concepts that are closely connected in your mind. The more these pathways are used, the more developed they become, and the more quickly and easily your thoughts traverse them.

Why: Focused-mode thinking allows you to take in detailed information or solve simple problems immediately by applying the steps of a solution method that you are familiar with.

Limitations: Oakley notes that focused-mode thinking is susceptible to the “Einstellung effect,” which occurs when you are unable to solve a problem because the solution is outside the range of ideas where you are looking for it.

(Shortform note: “Einstellung'' is a German word that Abraham Luchins used to describe this effect in 1942. The German word does not have an exact English synonym. In this context, it could be translated as “setting” (you get set in your ways) or “stopping” (you get stuck or stop making progress).)

For example, imagine that upon returning to your dorm room one day, you find that your roommate has bolted your car keys to a large, heavy object, and welded the nut onto the bolt. How do you get your keys back? Unless you are already familiar with this puzzle or prank from shop class, you will probably only be able to come up with brute-force solutions by focused-mode thinking: You think you’ll need a bolt cutter to retrieve your keys.

However, there is an easier solution: The bolt that your friend used is already cut in the middle, inside the nut. All you have to do is unscrew the bottom half of the bolt from the top half. However, the Einstellung effect may prevent you from recognizing this upfront.

Diffuse Mode

When: According to Oakley, diffuse-mode thinking happens whenever focused mode-thinking is not happening, such as when you relax or just let your mind wander.

How: Diffuse-mode thinking is associated more with the right hemisphere of the brain than the left (although both are involved), and with a resting state, where activity is not significantly elevated in any particular area of the brain. Oakley explains that during diffuse mode thinking, your thoughts traverse longer neural pathways between more diverse concepts.

(Shortform note: Researchers such as Raichle have identified a “default mode network”(DMN) in the brain that activates whenever it goes into a resting state. This DMN is where diffuse-mode operates. The DMN runs throughout the major structures of the brain and is not localized to any one part.)

Why: Diffuse mode thinking continues to subconsciously process information from previous focused-mode thinking but in a different way. It can generate creative ideas and creative solutions to difficult problems, circumventing the Einstellung effect by allowing you to mentally step away from detailed problems and see the big picture.

Oakley points out that this is particularly useful in math and science because creativity and problem-solving are closely related: You can often approach a problem in a variety of ways, but a certain approach may offer advantages for a certain problem. Thinking up alternative solutions can help you find the best method of solving the problem.

Limitation: Oakley also notes that once you devise a creative solution with diffuse mode, you still have to switch to focused mode to carry out the solution, because diffuse-mode thinking doesn’t process information in enough detail for full implementation. Furthermore, to keep the diffuse mode working on a given problem, you have to keep the problem in your mind by periodically revisiting it with focused-mode thinking.

Perspectives on the Two Modes of Thinking

Other writers have used a variety of terms for what Oakley calls “focused-mode thinking” and “diffuse-mode thinking.”

Edward de Bono

Edward de Bono coined the terms “Lateral Thinking” and “Vertical Thinking” for what Oakley calls diffuse mode and focused mode, respectively. According to de Bono, lateral thinking is a mechanism for generating new possibilities, while vertical thinking is a mechanism for analyzing possibilities and selecting between them. Thus, Oakley’s emphasis on using diffuse mode to generate creative solutions is consistent with de Bono’s presentation, as is her description of the analytical nature of focused mode. However, there is a subtle difference in how they distinguish between the two modes: To Oakley, the distinction is the difference between focusing on something and letting your mind wander. To de Bono, it’s the difference between creatively generating new possibilities and analytically eliminating possibilities.

Malcolm Gladwell

Malcolm Gladwell contrasted “conscious thinking” with “unconscious thinking” in Blink. Gladwell presents “conscious thinking” as a tool for rational decision-making. He points out that it follows a logical path: We can retrace our thought process if we need to explain our reasoning. He also points out that it is easily disrupted in stressful situations. These characteristics tend to imply that it requires focused attention. Thus, Gladwell’s “conscious thinking” closely resembles Oakley’s focused mode.

Gladwell presents a different application for unconscious thinking than Oakley does for diffuse mode: While Oakley recommends using diffuse mode to generate a solution to a technical problem by taking a break from focusing on the problem, Gladwell recommends using unconscious thinking to make assessments and decisions quickly. He presents it as a tool for intuitive decision-making. He also emphasizes that unconscious thinking operates quickly, automatically sorts through sensory information to pick out what’s relevant in the big picture, and follows a “mysterious” path in the sense that we can’t consciously retrace it.

The common threads that tie Oakley’s diffuse mode to Gladwell’s unconscious thinking are that they both involve stepping back from the details to see the big picture and they both operate unconsciously.

Daniel Kahneman

Daniel Kahneman wrote about “System 1” and “System 2” thinking in Thinking, Fast and Slow. He defined “System 1” essentially the same as Gladwell defined “unconscious thinking.” He then defined “System 2” as a conscious, rational, analytical mode of thinking that operates on the intuitive insights and suggestions generated by System 1. According to Kahneman, System 2 can either accept these insights, reject them, or further analyze them. He also states that System 2 has limited capacity, and any task that requires mental energy uses up some of this capacity. Thus, Kahneman’s System 1 is similar to Oakley’s diffuse mode, and Kahneman’s System 2 is similar to Oakley’s focused mode.

Kahneman’s description and application of thinking systems is more like Gladwell’s, but from almost the opposite perspective: Gladwell acknowledges that biases can introduce errors in unconscious thinking, but he points out that unconscious thinking can also be remarkably accurate. As such, he teaches you how to take advantage of it. Kahneman acknowledges System 1 as a natural and necessary mental function, but he focuses on the many types of biases that can cause System 1 to be wrong. As such, he teaches you to recognize System 1’s vulnerabilities and use System 2 to compensate for them.

Although the types of bias that Kahneman describes are less applicable to technical problems, this theme resonates with Oakley’s observation that once you identify a possible solution with diffuse mode, you still have to switch back to focused mode to work out the details and make sure the solution actually works.

Alternate Between Thinking Modes to Solve Difficult Problems

According to Oakley, solving any difficult problem requires an exchange of information between your brain’s focused-mode and diffuse-mode functions. Sometimes multiple cycles are required. So start by deliberately focusing on the problem and then deliberately divert your attention, allowing your brain to switch to diffuse mode. Repeat as needed, alternating between modes until you solve the problem.

Perspectives on Alternating Between Modes of Thinking

Other authors echo Oakley’s imperative to alternate between modes of thinking, but each seems to offer a different rationale for it:

To Oakley, it’s a matter of detail. Your diffuse mode can see the big picture and generate creative solutions to the problem at hand, but only your focused mode can flesh it out with enough detail to make it work.

To De Bono, it’s a matter of selection. Use lateral thinking (diffuse mode) to generate possible solutions, then use vertical thinking (focused mode) to analytically select the best one.

To Kahneman, it’s a matter of consequences and mental resources. System 1 (diffuse mode) operates automatically, but is prone to bias errors. System 2 (focused mode) consumes your limited mental energy, but can correct these errors. Thus, you operate in diffuse mode by default and switch to focused mode to analyze your diffuse mode’s suggestions, investing more mental resources in your analysis when the consequences of the decision are more significant.

Gladwell might argue that, at least in some cases, you don’t need to switch back to conscious thinking (focused mode) to solve a problem if you’ve adequately conditioned your brain’s unconscious (diffuse) mode for that type of problem. A case study supporting this assertion is that of Hyram Rickover, an engineer with remarkable intuition.

In The Rickover Effect, Theodore Rockwell describes Rickover’s involvement in the design of the cooling system for the first nuclear-powered submarine. Engineers initially performed a detailed analysis to determine the size of the cooling system, but when Rickover saw the result, he insisted it was too small. Based on his intuition, he ordered them to quadruple the capacity of the cooling system. When the submarine was finished, the cooling system proved adequate but not excessive: In this case, Rickover’s engineering intuition was more accurate than the detailed thermodynamic analysis.

That said, A Mind for Numbers focuses on learning subjects like engineering, not applying that subject knowledge later. Rickover’s intuition had been conditioned by many years of experience, which you typically don’t have when you enroll in your first thermodynamics class. And professors usually expect you to show your work, so writing down an answer based on intuition may not get you many points on an exam, even if your answer is close enough for practical purposes. Thus, Oakley and Gladwell would probably agree that, as a student, working out solutions in focused mode is a safer bet. Plus, it provides a good starting point for calibrating your intuition on those kinds of problems.

When to Switch From Focused to Diffuse Mode

Oakley recommends that you continue to focus on the problem as long as you are making progress, whether in solving it or just in understanding it. When you cease to make progress or become frustrated, switch to diffuse mode.

Oakley points out that sometimes people around you can sense nuances of your behavior and measure your level of frustration more accurately than you can. For example, maybe your spouse notices that you are typing more forcefully as you try to finish a report and invites you to take a break. Or maybe your study partner sees the tension rising in your facial expression and suggests a run to the cafeteria for a snack before tackling the rest of your physics homework. Listen to them.

(Shortform note: Turning this around, sometimes, you can help your study partners by suggesting a break when you see them becoming frustrated. In Emotional Intelligence 2.0, Bradberry and Greaves present tactics for reading people’s emotions. In particular, they note that raised shoulders or fidgety hand movements can be signs of distress or frustration.)

Is there ever a time when you should switch to diffuse-mode thinking before you stop making progress or start to become frustrated? Oakley would probably say yes: Although she doesn’t bring it up in the context of alternating between thinking modes, elsewhere in the book, she does highlight the importance of avoiding burnout by scheduling time for rest and relaxation. She points out that you can accomplish more by working at a sustainable pace and giving your diffuse mode time to operate than by spending too much time in focused mode and then suffering reduced productivity because you’re mentally exhausted.

When to Alternate Between Modes of Thinking

Oakley notes that the interval over which you alternate modes also affects your problem-solving. On the one hand, since diffuse-mode problem solving only operates on information leftover from focused-mode thinking, it can run out of information if you go too long between focused-mode sessions. Oakley recommends that, as a rule of thumb, you should refocus on the problem at least once a day.

Rapid Transitions to Diffuse Mode

To take full advantage of diffuse mode, you need to divert your attention from the problem until it no longer lingers in your conscious mind. How long does this take? Oakley says it typically takes several hours. This seems reasonable for many situations, but it seems like there could be exceptions. For example, suppose you have been studying physics in your dorm room for some time when suddenly you hear a gunshot outside. The subject of physics vanishes instantly from your mind.

Does a sudden shift in mental focus like this result in more time-efficient alternation between focused and diffuse thinking modes? Or does it purge the information from your conscious mind too fast for your diffuse mode to absorb it, making the diffuse-mode processing ineffective? Oakley does not address this question, and it is unclear to what extent this possibility has been investigated by the scientific community.

Either way, your diffuse mode would finish processing the data sooner, whether because it received less information or got a head start on processing it. According to Oakley, once your diffuse mode has finished processing, it’s time to switch back to focused mode. Thus, we infer that you should refocus on the problem sooner after a sudden transition to diffuse mode than after a gradual one.

How to Switch Between Modes of Thinking

Oakley doesn’t provide instructions for switching your brain to focused-mode thinking. She doesn’t need to, because, as she points out, focused mode activates automatically when you focus on something.

Deliberately switching to diffuse mode is a bit less intuitive, but Oakley presents several practical methods for diverting your focus so that your diffuse mode can operate. Here are a few methods from her list:

Go for a walk or do something athletic. Oakley states that physical activity is particularly effective for stimulating diffuse-mode thinking, and also promotes the generation of new neurons and neural pathways in your brain.

The Body-Brain Connection

The connection between physical exercise and mental health is a common theme among many self-help authors. While Oakley applies this principle to academics, Brenden Burchard applies it to professional productivity in High Performance Habits. Improving your health is one of the six habits Burchard identifies that contribute to improving your performance. He asserts that regular exercise, combined with a healthy diet and adequate sleep, will give you greater mental energy and mental clarity.

Meanwhile, Robin Sharma applies this principle to man’s quest for happiness, balance, and fulfillment in The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari. On the grounds that improving your mind will improve your body and improving your body will improve your mind, Sharma develops his “Ritual of Physicality” as one of his “Ten Rituals for Radiant Living.” This ritual consists of exercising for at least five hours per week, plus practicing deep-breathing exercises for a few minutes a few times each day.

Kelly McGonigal expands upon how exercise benefits mental health, happiness, and even relationships in The Joy of Movement. She observes that during physical exercise, your muscles produce chemicals called myokines, which circulate through your bloodstream. These myokines stimulate various parts of your body, including your brain. They increase your cognitive performance, as well as alleviating both physical pain and emotional depression.

Take care of routine tasks. Do housework or yard work, take a bath or do laundry, feed your pets, or work on other chores that don’t require intensive focus. Oakley notes that this approach is especially useful because we all have limited time: It allows you to apply diffuse mode thinking to complex problems and simultaneously make progress on other tasks that you need to complete.

(Shortform note: There are other benefits of this tactic as well. A recent study by Smith, Ng, and Popkin concluded that housework is a feasible means for workers with sedentary jobs and limited time to get the health benefits of physical activity. And psychologists such as Vivian Wolsk assert that these chores can also serve a therapeutic purpose by relieving stress and providing a sense of accomplishment.)

Rest and reflect. Reflection includes prayer, meditation, listening to music, and so on. As to rest, Oakley suggests that if you’re pressed for time, just close your eyes for a moment to avert your attention and avoid the Einstellung effect. She bases this suggestion on research by Nakano et al that suggests just blinking may involve a momentary break in focus that allows your brain to reevaluate your situation.

If you’re not pressed for time, get some sleep. According to Oakley, diffuse-mode thinking continues to operate while you sleep, so it’s a great way to give your diffuse mode time to operate. Sleep also plays an essential role in your brain’s ability to function: Oakley explains that when you’re awake, metabolic processes in your brain generate toxins that are expelled from the cells. When you sleep, your brain cells contract, increasing the space between cells. This allows the toxins to be washed out of the brain by cerebrospinal fluid and ultimately eliminated from the body.

Thus, Oakley cautions that if you don’t get enough sleep, the toxins in your brain can build up to the point where your brain can’t make all of the neural connections necessary for you to think normally. Consequently, one hour of studying with a well-rested brain will allow you to learn more than three hours of studying with a tired brain.

The Importance of Sleep

The importance of sleep for neurological health is echoed by numerous other authors.

In Moonwalking with Einstein, Joshua Foer points out that sleep is important for consolidating information in your brain. He cites studies performed on rats, where the rats’ neurons fired identical patterns during a maze exercise and when sleeping after the maze exercise.

Matthew Walker echoes this observation in Why We Sleep, asserting that sleep improves long-term memory of important facts, eliminates trivial information that would otherwise clutter up your memory, and enhances your motor-task proficiency. He also warns that lack of sleep impairs your ability to focus and to control your emotions, and increases your risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

In Essentialism, Greg McKeown stresses that getting enough sleep makes you more productive because it allows you to perform at your highest level. He asserts that sleep enhances your creativity and problem-solving abilities.

Exercise: Alternate Between Focused and Diffuse Thinking

Alternating between focused-mode and diffuse-mode thinking is important for stimulating creativity and problem-solving. In this exercise, you’ll optimize your schedule to promote alternating between modes of thinking and reflect on symptoms of the Einstellung effect that can alert you it’s time to switch to diffuse mode.

Of the things on your to-do list this week, which ones will require intensive focus? (For example, doing your taxes.)

Which tasks on your to-do list do not require intensive focus? (For example, doing the laundry).

How can you optimize your schedule to alternate between focused-mode and diffuse-mode thinking this week?

Exercise: Circumvent the Einstellung Effect

You can overcome the Einstellung effect (that is, the inability to solve a problem or to recognize a better solution because the solution lies outside the scope of the ideas you are focusing on) by switching to diffuse-mode thinking. In this exercise, you’ll analyze a recent experience with Einstellung and formulate a plan to overcome it.

Recall the last time you were stumped by a problem (at least temporarily). What were your symptoms of the Einstellung effect? At about the time you stopped making progress, how did you feel? If there were other people around you at the time, did they advise you to take a break or comment about how you looked/acted at the time?

Next time you experience these symptoms, what will you do to switch to diffuse-mode thinking? (Consider strategies like rest and reflection, routine tasks, or athletic activity.)

Part 2: Understanding Memory and Information Chunking

Continuing our discussion of your brain’s capabilities, in this section, we’ll focus on memory and the learning process. According to Oakley, you use both your working memory and your long-term memory to learn math and science, so we’ll start by discussing the distinction between them.

Then, we’ll discuss “chunking.” According to Oakley, chunking is the process in which your memories get consolidated into “chunks” of related information in your brain. From Oakley’s writing, we infer that chunking helps lay the foundation for understanding how your memory works because your working and long-term memory depend on your brain’s ability to organize information into chunks. We’ll build practical study habits on this foundation in later parts.

Working Memory Is Your Brain’s Workspace

As Oakley points out, working memory holds the information that your mind is actively processing. You use it to solve problems in math and science when you focus on the problem and think about the principles you would use to solve it. You also use it when you take in new information and try to make sense of it.

While Oakley doesn’t address this explicitly, there seems to be a strong connection between working memory and focused-mode thinking, since working memory holds information that you are focusing on. She does mention that people who have larger working memories tend to be more naturally disposed to focused-mode thinking, which reinforces this idea.

Your working memory has a limited capacity. On average, it can only hold about four “chunks'' of information at a time, although this varies from person to person.

(Shortform note: Not all sources agree as to exactly how many “chunks'' of information an average person’s working memory can hold. The number four comes from Cowan’s research, which was published in 2001, and largely supplanted an estimate of seven based on Miller’s work in 1956. Another study by Gilchrist and Cowan determined working memory capacity varies from about two to about six units of information, depending on the person. In 2003, Gobet and Clarkson published a study revising the estimate to between two and three. The important takeaway is that your working memory can only hold a few units of information.)

Oakley asserts that if your working memory cannot hold all the information it needs to solve a problem, mental “choking” occurs, preventing you from solving the problem. The “chunking” process (which we will discuss later in Part 2) helps to reduce your risk of choking by condensing information, leaving room for your brain to load all the concepts you need at once.

Oakley also points out that your working memory requires continual input of energy to retain information. She explains that chemical reactions in your brain continually clear your working memory to prevent it from filling up with trivial information, and they eventually erase anything your mind isn’t using.

She does not discuss whether these reactions play any role in alternating between focused and diffuse modes of thinking. However, if focused mode operates on the information in your working memory, and switching to diffuse mode is complete when the thought disappears from your working memory, then the speed of these reactions arguably determines how fast you can switch from focused mode to diffuse mode.

Perspectives on Choking

In cognitive psychology, most research on “choking” has focused on “choking under pressure,” where your working memory cannot hold enough information because one or more of your working memory slots are filled up with anxiety.

New research suggests that only people with higher-than-average working memory capacity are subject to choking under pressure. It is as if these people have an extra working memory bank that gets filled up or cannot be accessed under stress, while regular working memory remains accessible, both for them and for people who don’t have the extra memory bank.

Can your brain still choke if you’re not under pressure? In principle, yes. Based on Oakley’s description of choking, some problems might simply require enough information to solve that you can’t comprehend the whole solution until your brain has had a chance to condense some of the information into more compact chunks.

In practice, studies of information overload have proved inconclusive: It seems that your brain is naturally capable of sorting through large amounts of information to pick out what is relevant for solving a problem, provided you have time to do so.

Long-Term Memory Is Your Brain’s Library

Oakley explains that long-term memory stores information for future reference. To learn math and science, you have to take the new concepts that you’ve received into working memory and save them to your long-term memory so you can recall them when you need them (such as on an exam). We’ll talk more about how you transfer new information from working to long-term memory in the next two parts, but for now, let’s go over your long-term memory’s capabilities.

Oakley explains that, unlike your working memory, your long-term memory can store billions of chunks of information. Furthermore, the information does not dissipate as it does in working memory. However, chunks that you don’t access repeatedly may get buried under other chunks and become difficult to retrieve.

Diffuse Mode Memory

In light of this contrast with working memory, how does long-term memory relate to the two modes of thinking? Oakley doesn’t discuss this. Focused mode can retrieve information from long-term memory and load it into working memory where it makes use of it. Does diffuse mode operate directly on data in your long-term memory? Or does diffuse mode have its own unconscious version of working memory that absorbs information from your focused-mode working memory so diffuse mode can operate on it later?

Given Oakley’s assertion that diffuse mode eventually runs out of information to process, the second explanation seems to fit better. Furthermore, Gilchrist and Cowan have identified that there are both conscious and unconscious aspects of working memory.

Knowledge Collapse

Oakley explains that long-term memory is susceptible to a phenomenon called “knowledge collapse.” This happens when your brain has to reorganize the chunks in your long-term memory to restructure your understanding of something. As you learn a subject, you’ll reach certain points where some restructuring is necessary for your understanding to continue to grow. While the restructuring is going on, you may feel as though everything you knew about the subject has suddenly evaporated, but once it is complete, your understanding will be stronger than ever.

As an analogy for knowledge collapse, picture a warehouse where boxes are stacked on top of each other in orderly piles. Then the warehouse manager decides to install shelving. The boxes have to be taken down and moved out of the way to install the shelves, and so the inside of the warehouse looks like complete chaos during the installation. Yet once the shelves are installed and the boxes are stacked on the shelves, they are more orderly and more accessible than ever.

Elsewhere in the book, Oakley affirms that persistence is more important than innate intelligence when it comes to learning a difficult subject. If carried to its logical conclusion, the concept of knowledge collapse reinforces this: Since knowledge collapse is a natural part of the learning process, it’s normal to struggle with new material and periodically feel like you don’t understand it. Persevere through periods of knowledge collapse.

The Origins of Knowledge Collapse Theory

Oakley may have coined the phrase “knowledge collapse,” as it does not appear in other available literature about this phenomenon. However, she didn’t originate the theory of knowledge levels temporarily declining at certain points of the learning process. She cites the work of Fischer and Bidell, who discuss in detail the different phases of learning.

Fischer and Bidell observed that when you learn a skill, your progress follows a pattern that depends on your initial level of proficiency. If you’re completely new to the subject, chances are your knowledge of it will require such frequent restructuring that your progress seems chaotic: As soon as you think you are starting to understand it, you learn something new that shatters your current understanding of the concept. For example, suppose you are suddenly transported to a foreign country where nobody speaks English and you don’t know the local language. At first, you’ll just be guessing blindly to figure out what words mean as you try to communicate with people.

Fischer and Bidell report that as you reach an intermediate skill level, your progress follows a “scalloped pattern” where growth is repeatedly followed by sudden decline and then rapid regrowth. This is the phase of learning where their study best fits Oakley’s description of knowledge collapse.

Finally, according to Fischer and Bidell, once you become an expert in something, your progress hits a plateau, where your proficiency is high and remains relatively constant over time. At this point, you no longer experience knowledge collapse in the sense that Oakley describes it, although Fisher and Bidell still observed occasional tiny dips in the plateau of proficiency. Turning back to our language example, let’s say you now speak the language fluently. One of these knowledge dips might be hearing a word that you don’t know and having to look it up in the dictionary.

Chunking Is Your Brain’s File Management System

Oakley explains that everything you know is stored in your memory as “chunks” of information. The chunking process condenses information so that it will fit in your working memory, and gives it structure so that it can be organized in your long-term memory. Let’s look at what a chunk is, and then we will discuss how your brain builds chunks.

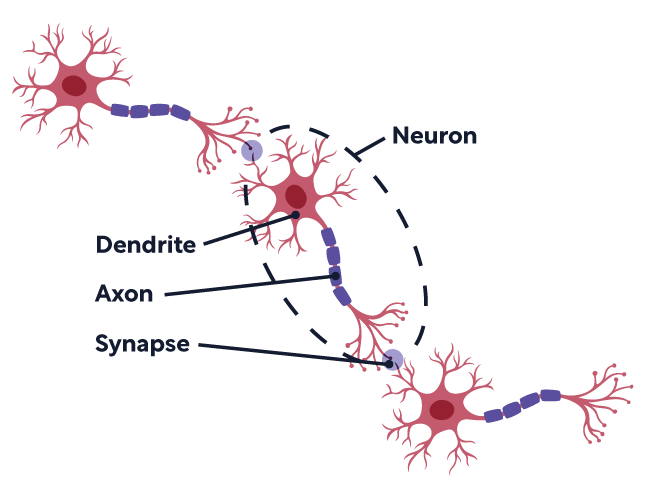

According to Oakley, a “chunk” physiologically consists of a group of neurons connected by synapses that fire in sync with each other. Learning is the process of forming these neural connections.

(Shortform note: Oakley references a study by Guida et al in which scientists used neuroimaging to study both novices and experts learning or performing certain tasks. They observed distinct patterns in brain activity that were different for the novices versus the experts: In the case of novices, researchers correlated these patterns to chunks forming in working memory; in the case of experts, they correlated these patterns to chunks being retrieved from long-term memory. By mapping the synchronized activity of the neurons that made up these chunks, this study appears to provide the basis for Oakley’s physiological description of a “chunk.”)

Conceptually, a “chunk” consists of a group of ideas or bits of information that are bound together in your mind through meaning. As you take in information, your brain tries to assemble it such that it makes sense: If the new information relates to something you already know, your brain makes the connection. If not, it still looks for unifying themes that make the facts easier to keep track of. Oakley asserts that the more deeply chunked something is in your mind, the more intuitive it becomes, and the less space it takes up in your memory.

As an example of the chunking process, think about learning to drive a car with a manual transmission: To shift gears, you have to push in the clutch, move the stick to the right position, and keep the engine RPMs in the right range while you let the clutch back out. You also have to control the steering wheel, operate the brake, keep track of your speed, and so forth. However, once you learn to drive a stick-shift, you don’t think specifically about all these little tasks. You just think, “I need to drive to the grocery store,” and pretty soon you’re cruising down the road in third gear, without any conscious recollection of how you shifted from first gear into second or second into third. This is because your brain has condensed all the little tasks into a single chunk of information that you can use intuitively.

The Discovery of Chunking

The discovery of chunking is generally attributed to George Miller, who studied working memory capacity in the 1950s. Miller observed that people could only distinguish between sensory inputs to a finite degree of precision. Specifically, most people could only distinguish between about seven levels of a given stimulus, such as tones of sound or shades of color.

Miller initially tried to describe his results in terms of digital information theory. When a computer measures a sensor input, it uses a series of electronic comparators wired to a digital memory bank. This generates a binary number in the memory bank that corresponds to the value of the measurement. The larger the memory bank, the more comparators we can wire to it and the more precise the measurement can be.

The size of a digital memory bank is expressed in “bits,” where a “bit” is a memory slot that can hold either a one or a zero. When Miller applied this analogy to humans’ working memory, he calculated that our brain’s sensory memory bank needed to hold about 2.8 bits of information to distinguish between seven levels of sensory input (since the limit of precision is equal to two raised to the power of the number of bits, and 22.8=7).

Miller also observed that people could only keep about seven items in mind at once, such as a string of seven numbers, letters, or words. This provided another measure of working memory capacity that gave the same result. However, in this case, Miller could not say that working memory had a capacity of “2.8 bits,” because letters and words take more bits than this to encode in binary.

Moreover, a string of seven words is made up of more than seven letters, and contains more information than a string of seven letters. Thus, if measured in terms of binary bits, the capacity of working memory seemed to vary, depending on what kind of information it held.

Miller coined the term “chunks” to describe the units of information in working memory, since “bits” didn’t provide a consistent measure: Based on Miller’s observations, your working memory could hold about seven chunks, but an almost unlimited number of bits.

To explain this, Miller theorized that your brain could organize information into increasingly complex chunks over time. As you learn something, your working memory quickly fills up with information, but once you process this information into a coherent chunk, it takes up only one slot in your working memory instead of all of them. Then, you can take in more new information and append it to the same chunk. In this respect, Oakley reiterates Miller’s description of how chunking makes room for more information in your working memory.

Artificial Chunking

Oakley and Miller both describe chunking as a mental process that occurs naturally as part of the learning process. However, others have explored applications of artificial chunking, both for humans and for computers.

In his book, Moonwalking with Einstein, Joshua Foer describes chunking as a mnemonic device: You can remember longer strings of numbers by breaking them up into groups of digits. This could be called “arbitrary chunking,” since you arbitrarily impose the grouping and artificially create a unifying meaning for each chunk of numbers.

Meanwhile, computer scientists Laird, Rosenbloom, and Newell took the concept of chunking and applied it to the problem of developing machine learning and artificial intelligence. They started with a problem-solving algorithm that was able to process specified goals and generate sub-goals that it could solve. They then programmed the computer to save “chunks” consisting of subgoals that it solved, packaged with their solutions. The computer could refer back to these chunks when solving new problems that had similar goals or subgoals, instead of generating the same solutions all over again.

Without chunking, the problem solver took 1731 processor operations to solve a certain benchmark problem. With their chunking algorithm, the computer was able to solve the same problem with only 485 operations on the first run, and only 7 operations when they ran the same problem again. Thus, it looks like artificial chunking has the potential to dramatically improve computers’ problem-solving capabilities, especially for repetitive problem solving.

Simplify Concepts to Expedite Chunking

Oakley explains that the more you distill a concept down to its essence, or figure out what it means at an intuitive level, the more tightly that meaning binds the chunk together in your mind. To help this process along, Oakley recommends trying to simplify concepts that you’re learning enough that you could explain them to someone who has little background in the subject. Because it helps with the chunking process, this exercise often enhances your own understanding. She notes that many teachers of her acquaintance say they didn’t really understand their subjects until they began preparing to teach them, and consequently simplified the subjects for the benefit of their students.

(Shortform note: In Ultralearning, Scott Young describes a similar technique for learning a new concept by pretending to explain it to someone else, which he attributes to physicist Richard Feynman. According to Young, the “Feynman Technique'' consists of writing out an explanation of the concept you are trying to understand as if you are explaining it to someone else. If, at any point, you don’t feel you can explain it clearly, you review your sources to clarify your understanding, and then finish writing your explanation.)

The Link Between Teaching and Recall

Four years after Oakley wrote A Mind for Numbers, a study determined that the effectiveness of teaching as a learning tool is closely related to the practice of intentional recall. Researchers concluded that the element of recall involved in teaching may be what makes teaching so effective for learning.

Given the results of this study, perhaps the act of teaching improves your understanding of something by making it more accessible in your memory, rather than by simplifying it.

Build Chunks From the Bottom Up

According to Oakley, chunking is a “bottom-up” learning process because it starts with the details and progresses towards the big picture: First you take in the information. Then you connect the information by understanding the underlying concept. Finally, you establish the context of the chunk, so your memory can file it where it will be most relevant. As Oakley points out, the more you understand why something works, the more easily you can understand how it works. Understanding whether or not the chunk is applicable in a variety of different situations also establishes multiple neural pathways to it, making it accessible when you need it.

As an illustration of the bottom-up chunking process, consider our example of learning to drive a stick-shift. The different gear positions and the method of letting out the clutch so you don’t stall the engine are pieces of information. As you develop these skills and learn to coordinate them, they become united in a chunk embodying the concept of shifting gears. As you gain experience, you develop a better understanding of when to shift into what gear (the context of the chunk). For example, you might normally go 55 mph in fifth gear, but use fourth gear at this speed if you’re driving uphill or pulling a trailer.