1-Page Summary

In Biased, social psychologist Dr. Jennifer Eberhardt compiles findings from her decades of research on the social and neurological roots of implicit bias. When you hear the word “bias,” you may think of conscious prejudice—but the most potent biases are actually subconscious. These implicit biases are normal neurological responses to the culture you grow up in.

In the United States, everyone holds some degree of (often subconscious) antiblack bias, even in black communities. This racial bias doesn’t just influence how you make decisions—it determines what you notice in your environment and what becomes invisible. And in high-stakes situations like police encounters, the consequences of racial bias can be devastating.

In this guide, we’ll learn how bias forms in the brain, how racial bias in particular influences police interactions and impacts every level of the criminal justice system, and how some people use science as a tool to promote racial bias. With this foundation, we’ll then look at how bias impacts every area of our daily lives. Finally, we’ll discuss how implicit bias can transform into explicit racism, as it did during the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

The Other-Race Effect Is a Form of Categorization

Before we get into the ways bias impacts various parts of daily life, let’s look at why bias exists in the first place: in other words, the brain functions that create it.

Have you ever heard someone say, “They all look alike” about people of another race? That comment doesn’t actually reflect a conscious prejudice—it’s the natural result of human biology. Scientists call this the “other-race effect”: the experience of being able to easily recognize faces of your own race but struggling to identify faces of other races.

The other-race effect is a form of categorization, which is a normal, subconscious brain function that helps us divide all the information we encounter into smaller categories that we can understand. Categorization is not a bad thing by default, but it can easily be hijacked into making harmful generalizations based on race (like, “all black men are dangerous”). Those generalizations are the root of bias.

(Shortform note: One way to avoid this mental reflex is to look for more individuating information about the person. In Superforecasting, authors Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner argue that any new piece of information we get about a person, no matter how irrelevant it seems, makes it harder for us to categorize that person. This is called the “dilution effect.”)

Bias in Science and Pseudoscience

Racial bias is a centuries-old phenomenon that began as a way to justify slave trading—over time, that bias solidified as leading scientists invented baseless theories that black people were not fully human and therefore fundamentally inferior to white people. This process is called scientific racism, and it’s still used to justify antiblack bias to this day. In particular, the association between black people and apes is still alive and well. Sometimes that association is explicit—like in the widespread “ape” and “monkey” comments online after the election of Barack Obama—but it more frequently happens implicitly. In fact, researchers found that the implicit association between black faces and apes is even stronger than the association between black people and crime. That means that even people who consciously confront their own biases can carry that unconscious ape association and thus see black people as subhuman.

Ape Jokes Have Deadly Consequences

Equating black people to apes is dangerous. In 2009, researchers studied the impact of the black-ape association on threats to assassinate Barack Obama. The researchers determined that the black-ape association—particularly in the form of a controversial political cartoon—directly contributed to the unprecedented number of threats on President Obama’s life. These threats were part of the reason the Department of Homeland Security authorized Secret Service protection for then-Senator Obama beginning in 2007, a full 18 months before he was first elected president.

Bias in Housing and Neighborhoods

Bias isn’t just a large-scale social phenomenon. It also impacts very personal decisions—like where to live. Antiblack racial bias led to formal housing segregation laws, and although those laws no longer exist, they laid the groundwork for the de facto housing segregation we see today.

The History of Segregated Housing

In the early 20th century in America, black people migrated northward en masse to escape persecution and look for economic opportunities. To keep black people out of their white neighborhoods, private housing developers began instituting official covenants that forbade white homeowners from renting or selling their homes to black people. These covenants were so widespread that by the time the Supreme Court banned them in 1948, black residents were banned from 80% of the neighborhoods in big cities like Los Angeles. (Shortform note: Whole books have been written on the subject of racist housing policies. For example, The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein examines segregated housing in the United States from a legal and historical standpoint.)

For over 30 years, racial covenants ensured that black homeowners and renters were crowded into tiny neighborhoods, completely segregated from their white neighbors. Those covenants are the origin of the segregated neighborhoods and ethnic ghettos that still exist today. Government policies didn’t help—they were even more discriminatory. For example, during the Great Depression recovery effort, government-built housing projects were racially segregated; later, after World War II, federal laws prohibited black veterans from using their GI Bill housing benefits to buy homes in white neighborhoods. (Shortform note: In The New Jim Crow, author Michelle Alexander describes how white elites enacted these laws as a way to keep black people at the bottom of the social hierarchy while ensuring they didn’t band together with poor white people to challenge the social order.)

Modern Segregation

Racial discrimination in housing is now technically illegal, but nearly 70 years of officially-sanctioned segregation has left its mark on American cities. Today, African Americans are more likely to live in segregated neighborhoods than people of any other race—regardless of their economic status. Furthermore, segregation is largely maintained by white people’s racial biases. Studies show that most white people wouldn’t move to a neighborhood that is even 30% black, citing fears of high crime rates and low property values.

“Space Racism” and Attitudes Toward Black Spaces

These biased attitudes toward black spaces reflect the idea of “space racism” that Ibram X. Kendi describes in How to Be an Antiracist. “Space racism” describes the combination of attitudes and policies that contribute to inequality between spaces that are primarily inhabited by people of one race. For example, the funding gap between majority-white and majority-black schools is an example of space racism because it reflects the racist attitude of people in power that white children deserve more resources than black children.

Bias in Schools

Racial bias also impacts the American education system. Even when black and white students attend the same schools, their educational experiences aren’t equal. White students take it for granted that they’re valued as individuals at school; black students don’t have the same guarantee. Even at a young age, they’re well aware of the stereotypes their teachers might believe, and many black students learn to defend against possible racist treatment by never fully letting their guard down in the classroom. That makes learning difficult because learning is a vulnerable act—it requires letting people in and being honest about what you don’t know or don’t understand.

Unfortunately, black students have good reason to be wary of bias in their schools. Research shows that black students are much more likely to be suspended than students of any other race. (Shortform note: The racial disparities in school discipline are linked to the racial disparities in the criminal justice system. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, school suspensions contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline because students who are suspended or expelled are more likely to get into trouble with the law.)

Reducing Bias in Schools

Thankfully, there are ways to reduce bias in the classroom. Effective strategies include empathy training for teachers, building trust between teachers and students, teaching accurate history of race relations and prejudice, and framing feedback as an expression of faith in a student’s ability to do better (which reassures students of color that criticism of their work isn’t an expression of bias).

However, many educators approach the problem of bias ineffectively by claiming they “don’t see color” as a way to avoid acknowledging race at all. But racial colorblindness isn’t possible—as humans, our brains naturally rely on color to help us distinguish items in our environment, so it isn’t really possible to “not see” it. Beyond that, colorblindness can actually increase racial disparities, because ignoring skin color naturally means ignoring the racial discrimination people face because of it. To reduce bias, educators need to acknowledge the specific struggles their black students face.

The Many Dangers of Racial Colorblindness

Eberhardt examines the “colorblind” approach to racial bias in the context of education, but colorblindness is a common problem in all types of conversations about race. For example, in How to Be an Antiracist, Ibram X. Kendi argues that ignoring race won’t eradicate racism because racist ideas stem from racist policies, not the other way around. Therefore, to fight racism, we have to start by attacking racist policies—and it’s impossible to identify racist policies if we can’t see race.

Similarly, in The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander argues that colorblindness is dangerous because it keeps us from seeing just how deeply entrenched racism is in public institutions like the criminal justice system. As a result, it’s easy to make the mistake of over-emphasizing personal responsibility and ultimately blame individuals for what is really a systemic problem.

Bias in the Workforce

Racial bias in the workforce is another massive, widespread problem. In fact, the unemployment rate for young black people is twice as high as it is for young white people.

The main driver of this disparity is racial bias in the hiring process. In one study, researchers sent out thousands of resumes in response to real job applications and discovered that applicants with stereotypically black-sounding names were half as likely to be contacted about the job than applicants with white-sounding names. Another study found that, regardless of gender or education level, white people get 36% more callbacks for jobs than black people.

(Shortform note: The racially biased criminal justice system is also a major driver of black unemployment. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander describes how people with criminal records have a harder time getting hired. In Chapters 4-5 of this guide, we’ll see how black Americans are more likely to be arrested and face harsher sentences than white Americans, which means black job seekers are more likely to have a criminal record.)

Bias Training

Many businesses looking to reduce workplace bias are following the example Starbucks set in 2018 after police arrested two black men in a Philadelphia Starbucks for the simple crime of asking to use the restroom before purchasing anything.

Starbucks’s corporate response to this incident is a model for addressing racial bias in the workplace on a large scale. Instead of just addressing the incident itself, Starbucks committed to confronting racial bias head-on by holding a four-hour implicit bias training for all 175,000 Starbucks employees. This training required closing down 8,000 Starbucks locations for the day, costing the company roughly $12 million.

“From Privilege to Progress”

The Starbucks incident also sparked change in another way. Melissa DePino (the white woman who filmed and tweeted the whole encounter) and Michelle Saahene (a Black woman who was the first to speak up during the incident) connected over their shared horror and frustration at the injustice they witnessed that day in Starbucks. Together, they launched "From Privilege to Progress," an organization devoted to bringing white and Black people together to fight systemic and interpersonal racism. Through speaking engagements and online activism, they empower people to push past awkwardness and have hard, necessary conversations about racism.

Bias in Cases of Police Brutality

Although bias forms as part of a natural process, it can be a dangerous and even fatal component of police encounters. To examine the ways racial bias impacts police brutality, Eberhardt breaks down the 2016 murder of Terence Crutcher (an unarmed black man from Oklahoma) by police officer Betty Shelby. Here are a few key ways that bias escalated that deadly encounter.

Deciding to Pull Over

Officer Betty Shelby and her partner were en route to a domestic violence scene when they first saw Terence Crutcher’s car stalled in the road. Why did Shelby abandon an actively violent situation and decide to pull over? Because racial bias can dictate where people focus their attention.

Scientists study this effect using subliminal priming (flashing words or images on a screen so quickly that participants don’t consciously realize it happened). When researchers primed police officers with either crime-related or neutral words before showing them photos of white and black faces, the officers who were primed to think about crime looked longer at the black face than the white face, but officers in the control group looked at the two faces equally. That might explain why Officer Shelby was drawn to the sight of a random black man while she was responding to an active crime scene.

(Shortform note: The link between racial bias and selective attention is well-established in science; however, Terence Crutcher’s death may not be the best example of this principle in action. Crutcher’s SUV wasn’t pulled over to the side of the road—it was stalled in the middle of the street, blocking traffic, which created a dangerous traffic situation. Under those circumstances, it makes sense for an officer’s attention to be diverted to the scene.)

Seeing Surrender as a Threat

Officer Shelby shot Terence Crutcher while he was walking away from her with his hands in the air, indicating surrender. But Shelby later testified that she fired the gun because she genuinely feared for her life. Why? Because racial bias primes people to see black people’s movements as more threatening by default. Research on the New York Police Department’s controversial “stop, question, and frisk” program (where officers had the liberty to stop anyone on the street if they deemed that person suspicious) showed that black people were more likely than white people to be frisked and to have physical force used on them, but they were less likely to have a weapon. It’s likely that Officer Shelby interpreted Terence’s movements as more suspicious than she would if he had been white.

(Shortform note: Some reviewers of Biased criticized Eberhardt for not mentioning that Crutcher's autopsy revealed he was high on PCP at the time of the shooting, which may have contributed to his erratic movements. According to her lawyer, Officer Shelby had completed drug recognition training and was aware that Crutcher was likely under the influence of the drug.)

Pulling the Trigger

The most crucial impact of racial bias is on behavior, especially for law enforcement officers, whose actions can have deadly consequences. Racial bias makes officers more prone to use violence against a black suspect than a white one. In a computer simulation study featuring pictures of people of different races holding either a gun or an innocuous object, police officers hit “shoot” faster for black people with guns than white people with guns. This explains why Officer Shelby was so quick to pull the trigger when she assumed Terrance had a gun, an action that had deadly consequences.

(Shortform note: Eberhardt doesn’t touch on the fact that Officer Shelby’s partner shot Crutcher with his Taser just seconds before Shelby fired the fatal shot. This begs the question: Why was Shelby’s first instinct to grab her gun rather than her Taser? Implicit bias may have led her to choose the deadlier weapon, but police training also plays a role: Experts say most officers get extensive firearms training but only “a few hours'' of Taser training. Officers are taught to think of their firearm as their “best friend.”)

Bias in the Criminal Justice System

Bias creates racial disparities at every level of the criminal justice system, from police stops to bail to death sentences.

Discretionary Stops

Police officers’ officially-sanctioned biases are on display when they make decisions about who to pull over for equipment-related violations (like expired tags or a broken tail light). It’s often up to the officers’ discretion to decide if a minor equipment issue is worth the time and resources it takes to stop someone. That freedom often becomes an excuse to act on unchecked biases: An analysis of 18.5 million traffic stops over six years found that black drivers are more than twice as likely to be pulled over for equipment-related issues than white drivers.

(Shortform note: Surprisingly, this type of discrimination isn’t illegal. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander describes how, according to the Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, it’s legal to use perceived race in the decision to pull someone over so long as race isn’t the only factor.)

The Cash Bail System

In the United States’ cash bail system, bail is money used as collateral to ensure that, if they’re released, the person in jail will return for their official trial and subsequent court dates. (If they don’t return, they’ll lose that money for good.) If the person can post bail, they’re free to go home until the trial; if not, they’re stuck in jail—sometimes for months. The court decides the bail amount for each person based on things like job stability and criminal record, which puts anyone who isn’t rich and white at a disadvantage. Young black men face the most discrimination in bail charges—on average, they’re charged 35% more bail than white arrestees.

The effects of pre-trial detention can be devastating, even for people who ultimately aren’t convicted of a crime. When people are locked up for months awaiting trial, they’re unable to work, pay rent, or take care of their children—and can lose their jobs, homes, and custody rights as a result. (Shortform note: Opponents of bail reform argue that, without collateral, people won’t show up for their court dates and so won’t face justice. However, states that have implemented bail reforms didn’t see significant changes in court appearances—most of the time, people still showed up, even without having money on the line.)

Unequal Sentencing

If a case does go to trial, the outcome is heavily influenced by racial bias. This is especially true in the states where the death penalty is still legal. When a murder victim is white, the murderer is significantly more likely to receive a death sentence than if the victim is black. That disparity both reflects and reinforces the biased belief that white lives are precious and deserve justice, but black lives are expendable.

Racial Bias Influences Jury Selection

One reason juries may be so prone to anti-black racial bias is that they are often overwhelmingly white. A 2010 study of eight southern states found evidence of widespread racial discrimination in jury selection, especially in cases where the defendant is eligible for the death penalty if they are found guilty. In some places (like Houston County, Alabama), this discrimination is so extreme that prosecutors dismissed over 80% of qualified black jurors in cases involving the death penalty.

From Implicit Bias to Explicit Racism

Until now, we’ve focused on the role of implicit biases that people often aren’t even aware they have. However, in the right circumstances, those implicit biases can bubble up to conscious awareness and become explicit racism. This was the case in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017, when hundreds of white nationalists and neo-Nazis descended on the campus of the University of Virginia (UVA) before a “Unite the Right” rally. That march and its aftermath marked a fundamental change in the national conversation about race.

On the morning of the rally, following a night of widespread violence and white terrorism, hundreds of heavily armed far-right protesters clashed with several thousand counterprotesters. The tension between the groups quickly escalated from shouting to all-out brawling. That violence turned deadly when a self-professed neo-Nazi plowed his car into a crowd of counterprotesters, injuring dozens and killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer.

The Resurgence of Explicit Racial Bias

The Charlottesville march was the largest public gathering of white supremacists in decades, but the hatred that fueled it had been simmering beneath the surface for generations. Experts think that the sudden resurgence in white nationalism and explicit racial bias has happened because suddenly, white people are “outnumbered.” The population is diversifying more and more, and white people (particularly white men) are no longer the unquestioned rulers of society. No longer being the dominant social group makes many white people feel threatened, so they embrace white supremacist ideas more openly as a coping mechanism.

“Unite the Right” Was a Prelude to the 2021 Capitol Attack

The Unite the Right rally marked a cultural shift in part because it was the largest public gathering of white supremacists in decades. Four years later, on January 6th, 2021, pro-Trump extremists stormed the United States Capitol building in an attempt to stop Congress from certifying Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election. Some commentators argue that the president’s failure to condemn white supremacy in Charlottesville emboldened the far right groups who ultimately participated in storming the capitol (indeed, many of the same protestors attended both events).

Shortform Introduction

Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do is a practical guide to the science of implicit bias, or the automatic assumptions we make about other people without even realizing it. These biases are the result of natural cognitive processes—we sort people into categories as a mental shortcut to make the world easier to understand. In the United States, antiblack bias is such an ingrained part of the culture that everyone encodes it to some degree, and that implicit bias impacts where we live, work, and study; how we interact with the criminal justice system; and where we focus our attention.

About the Author

Dr. Jennifer Eberhardt is a social psychologist, a professor, and a recipient of the 2014 MacArthur “genius” grant. She earned her Ph.D. at Harvard and taught at Yale before joining the faculty at Stanford in 1998. At Stanford, she co-founded SPARQ (Social Psychological Answers to Real-World Questions), a “do tank” (rather than a “think tank”) dedicated to turning academic research on racial bias into actionable solutions for real-world change. She also regularly works directly with police departments to train officers on how to recognize their own implicit biases and avoid the potentially deadly consequences of acting on those biases.

Eberhardt is considered the reigning expert on the science of racial bias. She’s been interviewed in TIME Magazine, on NPR, and on The Daily Show With Trevor Noah. Her work has been featured in The New York Times and the BBC. In 2020, she gave a TED talk about her research on bias and how companies and police departments can reduce bias.

Connect with Dr. Eberhardt:

The Book’s Publication and Context

Publisher: Viking Penguin

Biased is Dr. Eberhardt’s first book. It is the culmination of decades of academic research on how biases develop and why implicit biases are so hard to combat. In the book, she explores the role of racial bias in major facets of daily life, including policing and the criminal justice system, science, housing, schools, universities, and workplaces.

Historical and Intellectual Context

The book was published in March of 2019, right on the precipice of a renewed wave of protests against police brutality in response to the high-profile police killings of Elijah McClain (August 2019), Breonna Taylor (March 2020), and George Floyd (May 2020). It joined the national conversation about race and racism alongside books like So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo and How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi. Although those books are more well-known and spent months on bestseller lists, Biased was the first to take a more scientific approach to talking about racism.

The Book’s Strengths and Weaknesses

Critical Reception

Biased was well-received by both critics and readers. Forbes praised the book’s blend of science and storytelling, as did other writers of books on racial bias. The book was even endorsed by Vice President Kamala Harris, who read it while serving as a senator. Harris said, “We could not ask for a better guide to understand this reality [of bias] than Jennifer Eberhardt.”

Negative reviews of Biased center on its limitations. Some inferred from the book’s title that the book would explore bias against all minorities, when it focuses almost exclusively on Black Americans. Other reviewers felt the book is a “beginner’s guide” to the study of bias and may be too basic for those well-read on psychological biases.

Finally, one New York Times reviewer argued that Eberhardt fails to consider alternative hypotheses to explain her findings, such as social deference theory (which suggests that police can and should expect a certain degree of respect from civilians because police officers rank higher in the implicit social hierarchy). Through the lens of social deference theory, police mistreatment of black Americans isn’t the result of racial bias—it’s the result of police officers demanding deference from people they think are beneath them on the social hierarchy. However, black people may be so tired of being harassed by police that they refuse to defer, in which case the officers will use increasingly violent ways to demand respect.

Commentary on the Book’s Approach

Biased begins with a basic overview of how bias works in the brain, then explores how implicit bias impacts different domains of daily life, beginning with police brutality and criminal justice before moving on to topics like housing and education. As an academic researcher, Eberhardt primarily focuses on the association between antiblack bias and crime, so she’s organized the book to focus on her area of expertise first before showing how those same types of racial biases can impact other areas of life. This organization supports her main argument that the most prevalent stereotype about black people in America is the association between black people and crime—and that this particular stereotype is the main root of antiblack bias.

However, Eberhardt made a deliberate choice to address this topic not just as a scientist but through three relevant, intersecting identities: a social scientist, a black woman, and a mother of young black men. Balancing those perspectives makes the book accessible for all types of readers—there’s enough science to be authoritative, and enough humanity to keep you engaged with empathy instead of clinical detachment.

Our Approach in This Guide

While Eberhardt’s organization makes sense given her expertise, we’ve focused instead on the wider context of bias first—what it is, where it comes from, and how it’s become such a prevalent problem. We’ll start by discussing how bias works in the brain; then, we’ll add historical context by looking at the history of racial bias in science. With that background, we’ll examine how racial bias impacts housing, education, and the workforce to get a sense of how bias subtly impacts so many areas of daily life. That holistic understanding of how implicit racial bias works in general will make it easier to see the bigger picture by the time we discuss police brutality and criminal justice. It’s tempting to jump right into those hot-button topics, but they’re just the tip of the racial bias iceberg, so it’s important to fully understand the basics of bias in order to put those topics into perspective.

Finally, we’ll end with a discussion of the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. This chapter marks a tonal shift from the rest of the book and shows how implicit racial bias can bubble up into explicit racism. We’ve retained the book’s chapter numbers to help you refer back to the book.

Throughout the book, Eberhardt weaves in her own experiences of bias as a black woman and the mother of black sons. While these personal stories make the book engaging for the reader, this guide focuses more on the major principles of bias and the science behind them. Eberhardt’s goal was to present her research on implicit bias and describe how it connects to her journey as a researcher and a black woman, and her personal stories are a key part of achieving that goal. In contrast, our goal is to highlight the main ideas of the book and put them in context, so we’ve omitted those stories for the sake of concision.

Chapters 1-2: Bias Changes What You See

When you hear the word “bias,” you may think of a conscious form of prejudice. But Eberhardt argues that the most potent biases are actually unconscious, operating without any conscious input or even awareness.

These implicit biases are normal neurological responses to the culture you grow up in—they affect everyone. But, specific cultures create biases against different groups of people. In the United States, everyone encounters and encodes antiblack bias to some degree, even in black communities. This bias doesn’t just influence how you make decisions—it determines what you notice in your environment and what becomes invisible.

In this chapter, we’ll learn how bias develops through the other-race effect and categorization; then, we’ll discuss how that bias gets transmitted to others through parenting and the media. Understanding how bias spreads will help to clarify why racial bias impacts so many areas of daily life.

The Other-Race Effect

Have you ever heard someone say, “They all look alike” about people of another race? Those types of comments can be deeply offensive. (Shortform example: In 2018, Hillary Clinton came under fire for saying, “I know, they all look alike” after a reporter mixed up Senator Cory Booker and former attorney general Eric Holder, both of whom are black men.)

However, that sentiment doesn’t typically reflect a conscious prejudice—more often, it’s the natural result of human biology. Scientists like Eberhardt call this biological process the “other-race effect”: It’s the experience of being able to easily recognize faces of your own race but struggling to identify faces of other races.

Eberhardt says that the other-race effect is one of the neurological processes underlying bias because it makes us see people of our own race as individuals worth recognizing and people of other races as just representatives of a group, not individual people.

The effect is universal: If you’ve spent time around groups of people outside your own race, you may have experienced it yourself. It develops because your brain can’t absorb every detail of the sensory environment around you all at once, so it learns to prioritize whatever it sees most often and focus its attention there.

How the Other-Race Effect Develops in Infancy

As early as 1975, scientists had confirmed that infants are naturally drawn to faces more than other stimuli. One study even found that newborns less than one hour old prefer images of typical faces over images of scrambled facial features. However, this overall preference for faces tends to decline by the age of three months, which is around the same age that scientists first see evidence of the other-race effect. This suggests that babies begin life with a generalized preference for human faces, which then gets "tuned" by their environment into a preference for faces of a certain race. By the age of nine months, most infants can only recognize faces of their own race.

There are some exceptions to this rule—for example, one study found that Chinese and Vietnamese children who were adopted into white families between the ages of two and 26 months old were equally good at recognizing Asian and Caucasian faces later on. However, another study found that Korean children adopted into white families after the age of three are much better at recognizing Caucasian faces than Asian ones. Scientists think this might mean that being exposed to faces of at least two different races of people during the first two years of life might make it easier to recognize multiple races later on.

Racial Experience Changes the Brain

Eberhardt argues that the fact that your ability to recognize others’ faces depends on your experience with people of other races reveals something important about human brain development—cultural conceptions of race are so powerful, they can change how your brain functions. This is an example of neuroplasticity, which is your brain’s ability to change its structure and function in response to experience.

(Shortform note: Until the mid-twentieth century, scientists thought that neuroplasticity was impossible in adults because the brain was already fully developed; now, scientific research shows that adult brains can still change and grow new connections between neurons. How well your brain maintains the ability to adapt is partly determined by genetics, but your lifestyle is important, too: Research shows that people who exercise regularly, practice mindfulness, and keep learning new things have an easier time forming new neural connections.)

Scientists can track these changes in the brain using brain scans. However, until recently, there was no scientific evidence that facial recognition abilities (the brain process at the core of the other-race effect) could also change in response to experience with people of different races. Eberhardt and a team of neuroscientists set out to study this question using brain scans of the fusiform face area (FFA), where facial recognition happens in the brain.

In a 2001 study, Eberhardt and her team studied changes in the FFA when participants looked at pictures of people from their own race or other races. They tracked these changes using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a technology that allows researchers to track blood flow to different parts of a person’s brain while that person does a specific task. (Shortform note: Increased blood flow means the brain is routing more oxygen to that area because it’s working harder than usual (just like you breathe heavier when you sprint than when you lie down). Scientists call that increased blood flow “activation.”)

For both black and white participants, the team found that the FFA activated more when people looked at faces of people the same race as themselves. In other words, when you see a person of your own race, your brain automatically works harder to encode their specific features so that you can recognize them later. If you grew up surrounded by white faces, your brain prioritizes recognizing white faces; if you grew up surrounded by black faces, your brain prioritizes recognizing black faces. The conclusion: Parts of the brain actually change how they function depending on a person’s experience with race.

Positive Interracial Experiences Reduce the Other-Race Effect

Eberhardt’s team was the first to find evidence that a person’s experience with people of other races can change how their brain functions. Since then, other scientists have found similar results, even in other areas of the brain. In 2020, a group of researchers studied activation in a broader group of brain structures related to facial recognition in white participants while they looked at images of black and white faces. They found that the more positive interpersonal experiences a white person had with black people, the more the facial recognition areas of their brain lit up when they looked at black faces. In other words, having positive, high-quality contact with people of another race mitigates the other-race effect, making it easier to recognize individual faces of people of that race.

Categorization

According to Eberhardt, categorization is another factor at the root of racial bias. In the context of racial bias, categorization is the process of seeing people of other races as representatives of a homogenous category, rather than as individuals, and automatically making assumptions about people based on your experience with that category. For example, if someone grows up in a culture that associates black people with crime, they’re likely to assume that every individual black person they encounter is a criminal.

How Categories Form

Eberhardt emphasizes that categorization is an automatic neurological process, not a conscious choice. It’s the brain’s way of sorting chaos into order. Mental categories are a collection of all your beliefs, experiences, feelings, knowledge, and preferences relating to a particular thing. For example, when you think of the category “sports,” your mind automatically calls up images of people playing sports as well as all the information stored in your memory about different sports, their various rules, famous athletes, and so on.

The feelings and memories you associate with the “sports” category are here, too. Maybe you’re an avid basketball player, so thinking about basketball brings up happy memories and a feeling of confidence. On the other hand, if you were bullied in school for not being athletic, thinking about any sport might bring up painful memories. Either way, the moment you see something sports-related, your brain cues up all the thoughts and feelings you have about the entire category, starting with the strongest associations (so if you met your spouse at a college football game, that will come to mind much faster than the name of a famous baseball player).

This same process applies to groups of people. According to Eberhardt, whether we’re aware of it or not, we all internalize stereotypes and cultural beliefs about groups of people, and that information gets stored in the corresponding category. When you see an individual member of that group, your brain automatically pulls up the entire category—even parts you don’t consciously agree with or don’t even realize are there. That’s why, regardless of your conscious beliefs, seeing a single black person can bring to mind ingrained messages like “that person is dangerous” or “that person is good at basketball.”

(Shortform note: One way to avoid this mental reflex is to look for more individuating information about the person. In Superforecasting, authors Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner argue that any new piece of information we get about a person, no matter how irrelevant it seems, makes it harder for us to categorize that person. This is called the “dilution effect.”)

Stereotypes

Our natural impulse to group people into categories sometimes leads us to rely on reductive stereotypes. Stereotypes are automatic, culturally-instilled beliefs about a group of people that we assume apply to all members of that group, even when that’s not true (for example, the idea that all black men are violent is a stereotype).

Eberhardt asserts that, just like categorization, stereotyping is an automatic neurological process that serves a functional purpose. There is simply too much information in the world for our brains to process each individual thing separately. But when stereotypes are applied to people, they become a dangerous source of bias.

Relying on stereotypes to inform our understanding of other people leads to confirmation bias, where people seek out information that confirms what they already believe and ignore anything that challenges those beliefs. (Shortform note: To avoid confirmation bias, author Nassim Nicholas Taleb recommends a technique called “negative empiricism” in his book The Black Swan. Negative empiricism is the process of seeking out information that disproves your original belief. In the context of racism, if someone believed black people were more likely to commit crimes, they might look for evidence that black people are actually less likely to commit crimes than people of other races.)

For example, when researchers showed people photos of a black person’s face moving gradually from an angry expression to a friendly one, people who were more racially prejudiced against black people labeled the face “angry” for more frames than less prejudiced people. In other words, they interpreted the neutral expressions between angry and friendly as still “angry.” Their prejudice colored their perception in a way that confirmed their existing beliefs. Seeing what you want to see instead of what’s really there is the heart of bias.

Stop Your Stereotypes by Slowing Down

Relying on stereotypes may be a natural cognitive process, but unchecked stereotypes can cause real harm to people of color. One way to minimize your risk of accidentally causing harm is to slow down. Eberhardt touches on this idea in Chapter 10, and other writers have also discussed the connection between speed and bias. For example, in Blink, Malcolm Gladwell argues that when we make decisions too quickly, we don’t have time to take in all the relevant information, so our brains automatically fill in the gaps with stereotypes and assumptions. However, when you take a moment to stop and think before acting, you have more time to process the specific situation without relying on stereotypes.

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman explains why slowing down might help us avoid stereotypes in Thinking, Fast and Slow. Kahneman argues that human thinking operates in two different systems: System 1 is automatic, unconscious processing, while System 2 is conscious, effortful thought. System 1 thoughts can be completely involuntary and happen almost instantaneously, which is why System 1 is the home of bias and stereotypes. By slowing down and reminding yourself to apply conscious thought to a situation that invokes bias, you force your brain to switch from System 1 thinking to System 2 thinking, which makes it much easier to avoid relying on stereotypes.

Categorization in the Brain

As we’ve noted, like the other-race effect, categorization is a normal, mostly subconscious brain function that helps us process the enormous amount of information we encounter in everyday life. Within this process, we automatically prioritize information we use most often and rely on simplistic categories for everything else. Categorization is not a bad thing by default, but it can easily be hijacked into making generalizations based on race and stereotypes (like, “all black men are dangerous”).

According to Eberhardt, the other-race effect plays a role in determining the exact generalizations people make: People are automatically predisposed to focus on faces they’ve sorted into the “like me” category—even if they’re wrong about that categorization—and block out or ignore everything else.

Research on the impact of categorization shows just how powerful those in-group and out-group designations are. In one study, researchers showed participants computer-generated faces. The facial features were specifically designed to be racially ambiguous, but each face was shown twice: once with a hairstyle typically worn by Latinos, and once with a typically African American hairstyle. When they saw the same faces later on, Latino participants were significantly better at recognizing faces with the Latino hairstyle than the African American hairstyle—even though it was the exact same face.

Once the participants in this study categorized the face as a member of their own race based on the hairstyle, they automatically focused more on memorizing their features because human brains are primed to focus on in-group faces. Essentially, your brain sees faces of your own race as individuals—not just members of a reductive category—so it automatically focuses on encoding the unique features of those faces.

Resist Categorizing by Changing Your Focus and Experiences

Other authors also warn about the dangers of making assumptions based on categorization instead of looking at people as individuals. In Factfulness, author Hans Rosling refers to categorizing as “the generalization instinct.” He argues that we can overcome the generalization instinct by focusing on differences within groups of people and similarities across groups of people. For example, if your mental category for black men includes “good at sports,” you might challenge that by focusing on the countless black men who aren’t athletic, or by focusing on the number of professional athletes from other races. That way, you’ll remind yourself that not all black men are athletic, and not all athletic people are black men.

In Blink, Malcolm Gladwell also offers advice for resisting categorizing by spending more time with people from other races and cultures. This works because we unconsciously prioritize information that we use in daily life—so if you’re exclusively surrounded by white people, you’re more likely to slot everyone else into reductive categories instead of seeing them as individuals. However, if you spend more time with people of other races or seek out books and movies that highlight other groups’ experiences, you’ll unconsciously begin to prioritize information about those other groups rather than falling back on categories.

How Bias Spreads to Others

Now that we know how racial bias develops in individual people, let’s examine how it spreads to others. It’s important to understand how bias spreads in order to understand why racial bias is so pervasive throughout modern culture. Specifically, in the United States, antiblack bias isn’t confined to one specific region or type of person—it spreads through parenting and popular media into every corner of the country.

Biased Parents Raise Biased Kids

According to Eberhardt, parents are one of the strongest sources of the generational spread of antiblack bias. Young children form their understanding of the world by watching the adults in their lives. When those adults show racial bias—even through subtle cues like body language—kids pick up on the message: This person of another race is treated badly, so they must be bad. The more often they hear that message, the deeper they encode it and adopt it as their own belief.

The Implicit Association Test

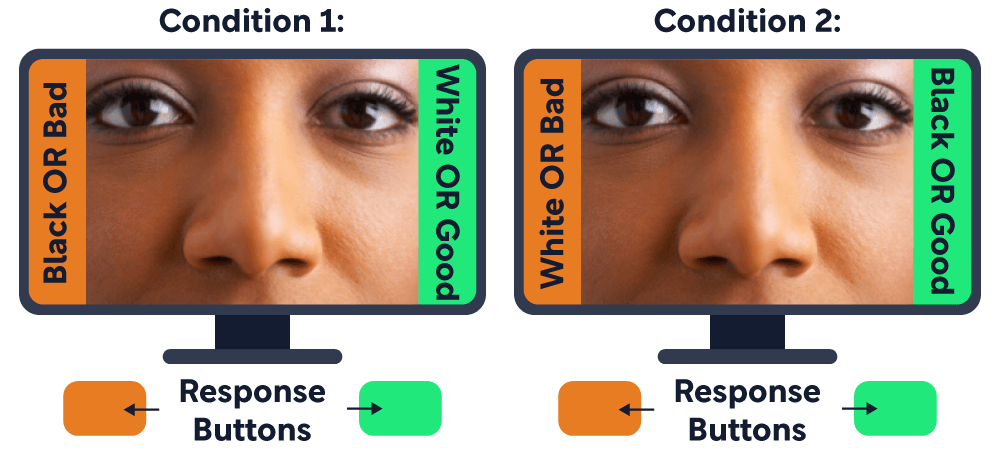

To test the impact of parents’ bias on their children, researchers use the implicit association test (IAT), which is the gold standard for testing the strength of implicit biases. The beauty of the IAT is that it doesn’t rely on self-reporting (which is often inaccurate because most people don’t want to admit to being racially biased). Instead, the IAT tests the power of biases operating below conscious awareness by measuring how quickly people associate black and white faces with good and bad words. (Shortform note: If you’re curious about your own implicit biases, you can take the IAT yourself through Harvard’s “Project Implicit.”)

To administer the test, researchers show participants a series of black and white faces on a computer screen interspersed with good words (like “joy”) and bad words (like “evil”). There are two conditions, both of which use only two buttons. In the first condition, participants push one button if they see a black face or a bad word, and the other button for a white face or a good word; in the second condition, participants push one button for a black face or good word, the other for a white face or bad word.

The idea behind the IAT is that culturally-ingrained bias makes it easier for the brain to associate black faces with bad words (and white faces with good words) than to associate black faces with good words (and white faces with bad words). In the first condition, the task is easy, so response times tend to be quick. But the brain has to work a little bit harder to associate black faces with good words, so the time it takes to push the right button is a little bit longer—the stronger the bias, the harder the brain has to work to associate “black” with “good,” and the longer it takes to respond. The IAT estimates the strength of a person’s implicit biases by measuring the difference between response times for the two conditions. When it comes to parenting, the results of the IAT confirm that heavily biased parents tend to raise heavily biased kids.

Parents’ Influence on Kids’ Racial Bias Fades Over Time

For young children, having a parent with strong implicit bias makes them less sympathetic when they see a black child being teased versus a white child. Interestingly, older children are typically very sympathetic to teasing victims of any race, regardless of how biased their parents may be. That might be because kids begin to form their own views of the world, separate from their parents, as they grow up and interact with more people.)

Bias in the Media

Bias also spreads through all forms of media. Growing awareness of media inequality in the early 21st century led to a major rise in the representation of black characters in leading roles in film and television. Eberhardt cautions that media representation is powerful, but seeing black surgeons and superheroes on screen is not enough to eliminate antiblack bias—in fact, it can even reinforce it. This effect is subtle and often subconscious, but still very real.

To test this effect, researchers took clips from shows that have strong, positive portrayals of black characters (including CSI and Grey’s Anatomy) and muted the sound. Then they compiled a series of clips of various white characters talking to the same unseen character (sometimes black, sometimes white), who was either offscreen or edited out. They showed these clips to study participants who had never seen that particular show and asked them to rate how much the white characters, as a whole, liked and respected the unseen character, based only on the white characters’ nonverbal cues.

The results of this study were significant: The offscreen characters that participants rated as less liked and well-treated by the other characters were significantly more likely to be black. In other words, white characters treated other white characters more positively than they treated black characters, and that difference was big enough that viewers picked up on it even without dialogue.

The perceivable bias in well-meaning TV shows isn’t just unfortunate—it’s dangerous. After viewing the clips, participants took an implicit association test. The more negatively they perceived the show’s white characters’ behavior toward the offscreen black characters, the more antiblack bias they showed on the IAT—even when they didn’t know the poorly-treated unseen characters were black. These results show that creating more positive roles for black characters isn’t enough to actively combat antiblack bias in the media.

Could Inclusion Riders Solve Popular Media’s Bias Problem?

An increase in positively-portrayed black characters on TV is a good first step, but the overall media landscape is still far from equal. A study of the 100 highest-grossing films of each year from 2007-2015 found that black characters made up 12% of speaking roles. While this might seem promising because black people make up roughly 13% of the American population, it’s not the full picture because a few movies with majority-black casts skewed the results. In fact, in 2015, only 10 of the top 100 films were cast in a way that reflects the actual population (meaning they featured black people in roughly 13% of the film’s speaking roles). Even worse, a full 17% of films featured zero black characters in speaking roles.

How can we solve this problem? Inclusion riders are one possibility. Inclusion riders (also called equity riders) are contractual clauses stipulating that the cast and crew of a film must include people from underrepresented groups in the industry, like women, people of color, and people with disabilities. If big-name actors and filmmakers add inclusion riders into their contracts, they can leverage their fame to open doors for talented people and ultimately create a more realistically diverse film industry.

Exercise: Reflect on Your Experiences With Bias

Racial bias impacts people of every race. Take a moment to reflect on your experience with bias and your motivation for engaging with this subject.

When you think of racial bias, what images and associations come to mind? (For example, you may think of a moment in your own life, historical examples of bias, racially segregated neighborhoods, or more recent police shootings.)

When do you remember first becoming aware of racial bias? How old were you, and what experience opened your eyes to the fact that racial bias exists?

Racially biased ideas can lurk in everyone’s mind, regardless of race or conscious beliefs, because we all grow up in a heavily biased culture. When have you noticed biased thoughts or first impressions in yourself? How did you feel when you noticed that implicit bias in yourself?

Finally, what do you most hope to get out of this guide? (For example, maybe you want to better understand how bias works in the brain, or maybe you’re looking for practical tips to reduce the impact of bias in your workplace.)

Chapter 6: Bias in Science and Pseudoscience

Unfortunately, racial bias isn’t a new trend. Racial bias is a centuries-old phenomenon that began as a way to justify slave trading. Over time, that bias solidified as leading scientists invented baseless theories that black people were not fully human and therefore fundamentally inferior to white people. This process is called scientific racism, and it’s one of the biggest reasons that racial bias has persisted for so long.

The History of Scientific Racism

Scientific racism is the false theory that different racial groups have fundamentally different physical and mental traits. According to Eberhardt, supporters of this theory believe those traits are universal, immutable, and objective, meaning that white supremacy and black inferiority are facts of nature rather than social constructs. Throughout history, scientists and academics have used scientific racism to justify their own racial bias as well as the entrenched racial inequality in their societies. (Shortform note: Some scholars, like Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Antiracist, use the term “biological racism” to describe these same ideas.)

As we’ll see below, scientific racism began with scientists inventing “natural” racial hierarchies, then evolved over time into a debate on the biblical origins of race, and finally adapted to fit the new understanding of human evolution and natural selection.

Phase 1: Human Hierarchies

In the 19th century, several prominent scientists published supposed hierarchies of humanity based on differences in physical and mental traits. Respected doctors and scientists wrote what they considered to be purely objective scientific texts asserting that black people were an entirely different species and therefore naturally inferior to white people.

Eberhardt argues that the original goal of these texts was to defend Europe and America’s economic interests in the slave trade against moral or religious objections. Scientists of the time provided the perfect cover: Black people were fundamentally, biologically inferior to white people and servile by nature, so slavery was simply part of the natural order of things. That “scientific” justification absolved white slaveholders of any guilt over kidnapping and enslaving fellow human beings. Over time, justifying bias and prejudice against black people became a fundamental part of mainstream science.

(Shortform note: While there’s no excuse for prejudice, author Jordan Peterson argues in 12 Rules for Life that the urge to establish social hierarchies is an evolutionary instinct that humans share with other animals, such as lobsters.)

Many of the scientists providing these false justifications for slavery focused on the size and shape of human skulls to prove their points. The most infamous of these scientists was American physician Samuel George Morton, who believed that the size of a person’s skull was a direct indicator of their intellectual ability. He collected thousands of human skulls from around the world, categorized them by race, and measured their capacity by filling them with lead pellets. Morton concluded from those studies that white Europeans were the most intelligent (and therefore most evolved) humans, and that Africans and Native Americans were separate, inferior species.

(Shortform note: Many of the skulls Morton collected belonged to people who had been enslaved. After his death, Morton’s collection ended up at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. In 2020, in response to the national wave of antiracist activism, the museum removed the skulls from public display and formed a committee focused on repatriating the skulls of enslaved people.)

Morton’s ideas about skull capacity and human intelligence became the foundation of the field of physical anthropology, which uses physical anatomy to study human behavior and culture. As we’ll see, physical anthropology would go on to become a hotbed of scientific racism.

Phase 2: Polygenesis

In the highly religious culture of 19th century America, the idea that black people and white people were entirely different species presented a challenge: Christianity only recognizes one creation story, not two, so all humans should theoretically be the same species. Eberhardt tells us that religious writers were divided on this question: Some supported the theory of monogenesis (a single creation story), others supported polygenesis (multiple creation stories). Supporters of monogenesis believed that all of humankind originated from Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden; supporters of polygenesis believed that there were separate creation events for each race, but only the creation of white people was important enough to be included in the Bible.

In 1854, writers Josiah Nott and George Gliddon merged polygenesis and the pseudoscience of human hierarchy into a single idea: White people originated from Adam and Eve, but people of all other races were created separately, more akin to animals than to the first humans. This led them to conclude that slavery was the natural order of the universe.

Justifying Slavery With the “Curse of Ham”

In How to Be an Antiracist, Ibram X. Kendi describes another common religious justification for racism during this period: The “Curse of Ham,” based on the biblical story of Noah (of ark-building fame) cursing the descendants of his son, Ham, to serve as slaves to one of his other sons, Shem. Although there’s no mention in the story of Ham having dark skin, proponents of slavery claimed that all Africans were descended from Ham’s line and therefore destined to be enslaved.

Justifying Polygenesis With Science

Like other scientific racists of the time, Nott and Gliddon focused on comparing human skulls to make their point. At the time, most scientists believed that brain size was linked to intelligence—to them, a larger skull meant a larger brain, which meant higher intelligence. Therefore, to prove white people’s superiority, these scientists set out to prove that white people had larger average skull sizes than black people. However, in reality, Eberhardt tells us that there is no difference in average skull size between people of different races.

(Shortform note: Modern scientists have found a correlation between skull measurements and geographic origin. However, that doesn’t mean that science supports using skull measurements to identify different races, because race and geographic origin are not the same thing. Geographic origin is the continent where your ancestors came from; race is the social category you fall into based on traits like skin color or language.)

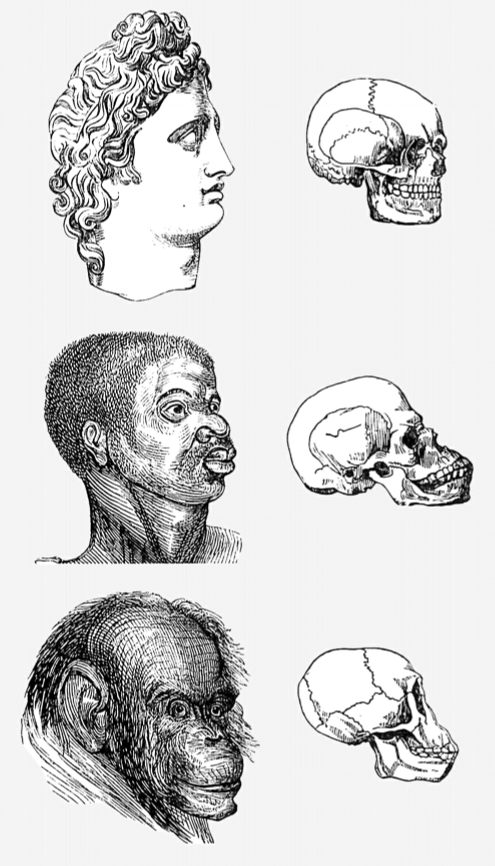

Without actual physical evidence, scientists had to rely on grossly exaggerated sketches of human skulls to show the biological differences they claimed to have discovered. These sketches became the template for the racist caricatures we still see today.

For example, the image below (from Nott and Gliddon’s 1854 book Types of Mankind) claims to show the skulls of a white person, a black person, and a chimpanzee. Eberhardt believes that the authors’ goal was to make it abundantly clear to even non-scientist readers that black people were biologically closer to apes than human beings. In the illustration, the black person’s skull is contorted beyond recognition—it’s arguably even less human-shaped than the chimpanzee skull—and the black face beside it is an early example of racist caricature. On the other hand, the drawing of the white person’s head is exaggerated to the other extreme: It’s based on a statue of the Greek god Apollo, which many consider to be the pinnacle of physical attractiveness.

Types of Mankind and Harvard’s Complicated History of Racial Bias

The original citation for Types of Mankind includes “additional contributions” from other authors, including Louis Agassiz, a Swiss-American scientist and Harvard lecturer who was well-known at the time as the founder of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. As a Harvard biologist, Agassiz lent a sense of academic credibility to the book, as the primary authors were not biologists—Nott was a surgeon and Gliddon was an Egyptologist. By attaching his name and his academic clout to the book, Agassiz helped make Types of Mankind an instant best-seller.

While at Harvard, Agassiz also commissioned a series of daguerreotypes of enslaved men and women, shown without clothing, that became some of the earliest surviving images of enslaved people in America. In 2019, the university came under fire when Tamara Lanier—a direct descendant of two of the people featured in the daguerreotypes—sued the university for profiting off the images of her ancestors, who wouldn’t have been able to legally consent to having their picture taken. Although she lost the case, Lanier’s lawsuit exposed the lingering influence of Agassiz’s racism at Harvard, prompting internal changes. Until 2019, the website for the Museum of Comparative Zoology lauded their founder as a “renowned teacher of natural history”; now, the site features a large “Black Lives Matter” banner across the main page and an official statement denouncing Agassiz’s ideas.

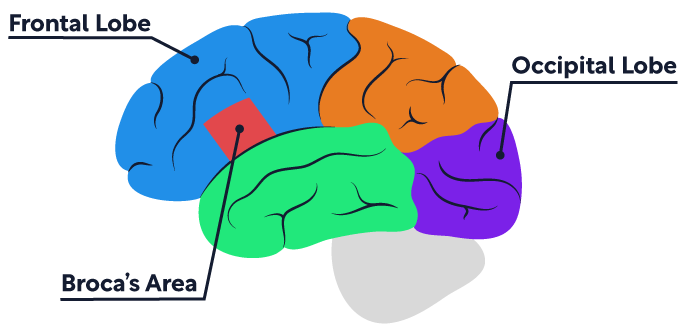

Around the time Nott and Gliddon were creating these racist sketches, French scientist Paul Broca discovered that brain function is localized, meaning certain physical areas of the brain are responsible for certain functions (like speech, emotions, sensory perception, and so on). Today, Broca is best known for discovering the brain region responsible for producing coherent speech—that region is still called “Broca’s area” in his honor—but few people know the racist motivations for his discoveries.

Broca was a firm believer in polygenism and the basic tenets of physical anthropology. However, according to Eberhardt, Broca’s understanding of brain localization added another layer of complexity to these concepts by examining the shape of the skull. He understood that basic functions like sensory processing happened closer to the base of the brain (the occipital lobe) while more complex functions like logical reasoning happened in the upper front of the brain (the frontal lobe).

This knowledge shaped Broca’s theory that differences in skull shape predicted differences in intelligence: Someone whose skull was larger in front must have a larger frontal lobe (and be more intelligent) than someone whose skull was larger in the back (and therefore had less capacity for rational thought). Like other European scientists at the time, Broca believed that all black people had more forward-jutting skulls than white people, with a larger capacity at the base than the front; consequently, they must also have overdeveloped occipital lobes and underdeveloped frontal lobes. Broca offered up this theory as a way to explain what he saw as the natural, inborn intellectual and social inferiority of black people as a whole.

(Shortform note: Broca’s discoveries were based on the pseudoscience of phrenology, or the idea that localized brain functions created unique shapes and features in a person’s skull. Phrenology proponents believed that tiny bumps and craters in different parts of someone’s skull were clues to their intelligence, personality, and moral character. Today, scientists know that brain functions are localized, but not in the highly pinpointed way that phrenologists believed, and those brain areas don’t impact the shape of the skull based on how well they function.)

Phase 3: Evolution and IQ

Shortly after Nott and Gliddon published Types of Mankind and Broca discovered his eponymous brain region, Charles Darwin rocked the scientific community with his theory of evolutionary biology in On the Origin of Species. Darwin argued that all humans were part of a single species that originated in Africa; but as we spread out over the world, different groups of people evolved differently to suit their unique physical environment.

According to Eberhardt, the new theory of evolution effectively ended debates on polygenism, but it could not wipe out scientific racism. Instead, scientists found new theories to justify racial bias: If humans are capable of physical evolution, then white people must be the most evolved humans. In that worldview, any non-white person represented a more primitive stage of evolution.

By the early 20th century, most scientists accepted Darwin’s ideas, and false theories about skull size and intelligence began to fade. In their place came a new tool for scientifically “proving” white intellectual superiority: the intelligence quotient (IQ) test. The IQ test is not a neutral, objective measure of intelligence. It was specifically designed to quantify the overall intelligence of different racial groups, provide “objective” evidence of white superiority, and use that evidence to justify and reinforce racial bias in existing institutions.

The Link Between IQ Tests, Scientific Racism, and Eugenics

The modern IQ test was first developed by French psychologist Alfred Binet in 1905. During World War I, the U.S. Army administered the test to millions of recruits, which paved the way for the widespread use of IQ tests. At that time, scoring well on the test required extensive knowledge of upper-class American pop culture, which meant that recent immigrants and working-class people (many of whom were people of color) were at an automatic disadvantage—unsurprisingly, rich whites scored far higher on IQ tests than any other group. The growing eugenics movement in the United States used these score differences as proof of a fundamental difference in intelligence between racial groups.

In the years following World War I, eugenicists were increasingly using IQ tests to identify candidates for forced sterilization and institutionalization. In 1927, the Supreme Court upheld states’ rights to sterilize “feebleminded” people (as identified by IQ tests) without their consent in the Buck v. Bell ruling; in the following 10 years, 28,000 Americans were forcibly sterilized. During the Nuremberg trials after World War II, Nazis specifically cited Buck v. Bell as inspiration for their own eugenics programs.

The Lasting Impact of Scientific Racism

Unfortunately, scientific racism is not just a historical phenomenon. Old ideas about black inferiority are so deeply ingrained in Western culture that they persist to this day. In particular, the association between black people and apes is still alive and well, whether we’re consciously aware of it or not.

Modern Confusion About “Biological Race”

Most modern scientists have abandoned the idea of “biological race” (that is, the idea that racial groups are biologically and genetically distinct from one another), but these ideas are still prevalent in the general population. In fact, nearly 53% of Americans believe that “biology determines your racial identity.” However, biological anthropologist Alan Goodman argues that there’s often more genetic variation between any two people of the same race than between different racial groups.

Goodman also tackles the common misunderstanding that sickle cell anemia is proof of biological race because it’s most common in people of African descent. While that is true, the reality is more complicated: The gene variant that causes sickle cell anemia is common in West Africa (as well as India, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East), but practically nonexistent in the rest of the African continent. That means that not all black people are susceptible to sickle cell anemia, and not everyone who carries the genes for the disease falls under the racial category of “black.” In other words, race isn’t the determining factor—geography is.

The Ape Association

Sometimes, the association between black people and apes is conscious and explicit. For example, Eberhardt describes how, in 2016, leaked text messages between San Francisco police officers showed similar dehumanizing language comparing black people to wild animals. And after the election of Barack Obama, online media exploded with racist animal comparisons targeting not just the president but his entire family—including his young daughters.

(Shortform note: It’s difficult to quantify just how common this form of racism really is because it often plays out on a much less public stage. For example, the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University publishes a selection of private letters it receives every year, including a 2012 letter arguing that black people are "closer to apes than to humans" and a 2017 letter accusing the museum of enabling “monkey children” to become rapists and murderers.)

However, this particular form of bias isn’t always so blatant; the implicit association between black people and apes lurks quietly in our collective subconscious. Eberhardt covers a few studies of subliminal priming uncovering racism:

- People subliminally exposed to line drawings of apes focused longer on black faces than white faces in implicit association tests.

- In the famous “invisible gorilla” test of selective attention, participants primed with stereotypically black names (like Jamal and Shaniqua) notice the gorilla 70% of the time, compared to just 45% of participants primed with white names (like Brad and Katie).

- In another study, participants who were primed with ape-related words (like “gorilla”) and viewed a video of police officers beating a suspect were more likely to say the violence was justified when they were told the suspect was black. When they were told the suspect was white, the priming didn’t have an effect.

These studies point to an implicit association between black people and animals. This is dehumanizing, and it makes people more likely to condone violence against black people since they implicitly see them as subhuman. The fact that this operates at a subconscious level is concerning—even people who work hard to avoid conscious racial bias can actively contribute to increased violence against black people.

Can Priming Studies Accurately Measure Implicit Bias?

The use of priming techniques in social psychology studies has come under fire in recent years. Critics claim that the results of priming studies often can't be replicated, which is concerning because replication is a crucial part of determining whether researchers have stumbled on a real phenomenon. If their results can’t be replicated by other researchers in other places, they’re more likely to be a statistical fluke.

To complicate things further, there are many different types of priming, some of which are easier to scientifically validate than others. Many of the studies on implicit racial bias rely on subliminal priming, where participants are exposed to stimuli (like faces or words) so quickly that they’re not consciously aware of it. A 2018 analysis found that the experimental design of subliminal priming studies makes all the difference—in other words, studies that were properly designed found much more reliable results than studies that used less scientifically-robust methods. The same analysis also highlighted the importance of using EEGs to directly monitor participants’ neurological responses to priming.

Other studies of implicit bias rely on supraliminal priming, where participants are consciously aware of what they’re seeing (such as news reports). Scientists haven’t tried to replicate these particular studies yet, so it’s hard to say whether the results are reproducible.

Implicit Racial Bias in Modern Science

Like many modern scientists, Biased author Jennifer Eberhardt frequently presents the results of her studies at academic conferences. When she first presented her findings on the black-ape association, she expected her colleagues to be skeptical and shocked. Instead, they accepted her research easily—the fact that most people have an implicit mental link between black people and apes made sense to them.

However, these same scientists questioned Eberhardt’s conclusion that the black-ape association is a form of racial bias; instead, they argued that her results were probably just a case of color matching. Their logic was that black people and apes are both dark in color, so it makes sense that seeing one would make people more likely to notice the other (in reality, most of Eberhardt’s studies used line drawings or words, not color images, so the color matching theory falls flat).

There’s a disconnect between theory and experience here: Eberhardt’s white colleagues see racial bias as an abstract concept because they lack the context of lived experience. Without that perspective, they don’t realize that rationalizing the black-ape association is a form of racial bias in itself. They’re essentially saying, “It makes sense to equate black people with animals because they really are more like animals than white people are,” even if they’re not consciously thinking that.

Ape Jokes Have Deadly Consequences

The idea that the black-ape association is logical, harmless, and not about race is dangerous. In 2009, researchers studied the impact of the black-ape association on threats to assassinate Barack Obama. The researchers determined that the black-ape association—particularly in the form of a controversial political cartoon—directly contributed to the unprecedented number of threats on President Obama’s life. These threats were part of the reason the Department of Homeland Security authorized Secret Service protection for then-Senator Obama beginning in 2007, a full 18 months before he was first elected president. The researchers found that many of the “ape” and “monkey” comments levied against the Obama family were written off as jokes. However, in the context of hundreds of years of people using the ape association to justify discrimination and violence against black people, those “jokes” become genuinely dangerous.

Exercise: Compare the Impact of Images and Words

Early images from racist scientific texts are the precursors to modern racist caricatures. Compare the impact of those images to biased speech and writing.

This chapter included an image from the book Types of Mankind that compares sketches of a white person’s skull, a black person’s skull, and a chimpanzee skull. What did you first notice about the image? What stuck out to you?

What thoughts or emotions did that image bring up for you? Why do you think you reacted that way?

You may have seen more recent images that are similarly biased (for example, in magazines, on Facebook, or in journalistic cartoons depicting figures like Barack Obama or Serena Williams). What ideas about race do you think the artists were trying to convey? Who is the target audience?

In cases like this, do you think an image really is “worth a thousand words”? Do racist images have a different impact than biased speech or writing? Why or why not?

Exercise: Think About the Black-Ape Association

The implicit association between black people and apes hasn’t faded with time. Think about why this particular form of bias is so persistent.

Why do you personally think the black-ape association has persisted for so long? Explain your reasoning.

Do you think that animal association will ever fade for black people the way it did for Irish American immigrants? If so, what needs to change in order for that to happen? If not, why not?

Chapter 7: Bias in Housing and Neighborhoods

So far in this guide, we’ve learned how bias works in the brain and the history of racial bias in science. Now, we’ll see how bias impacts very personal decisions—like where to live. Today, segregation and racial bias in housing is a major problem, especially in large cities. This problem stems from a long history of racist policies that severely limited where black people could buy or rent property. Although most of those policies no longer exist, they created a pattern of de facto segregation that persists to this day.

(Shortform note: Whole books have been written on the subject of racist housing policies. For example, The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein examines segregated housing in the United States from a legal and historical standpoint.)

In this chapter, we’ll explore the history of racist residential policies, the link between housing discrimination and ideas about cleanliness and disease, and the way those ideas play out on modern platforms like Nextdoor and Airbnb.

The History of Segregated Housing