1-Page Summary

Many enterprises come and go, but visionary companies endure for generations. These companies are the gold standard in their respective industries, remaining prosperous throughout many decades and at the hands of many different leaders. Beyond attaining financial success, they’ve also become household names—it’s hard to imagine a world without them or their products, from Band-Aids to Post-it Notes to Mickey Mouse.

But what is the key to these companies’ longevity and tremendous success? Bestselling author Jim Collins and Stanford professor Jerry I. Porras embarked on a six-year research project to answer this question and give practical advice for those who want to build a company that lasts.

After an exhaustive survey, the authors came up with a list of visionary companies with long life spans and unparalleled success. The authors then identified a comparison company for each visionary company—one that was founded at around the same time, that had the same founding products and markets, and that were also highly successful, but not to the degree that the visionary companies were. The 18 visionary companies (and their comparison companies in parentheses) are:

- 3M (Norton) - consumer products

- American Express (Wells Fargo) - financial and travel services

- Boeing (McDonnell Douglas) - aviation

- Citicorp (Chase Manhattan) - banking

- Ford (GM) - automotive

- General Electric (Westinghouse) - conglomerate (power, energy, aviation, health care)

- Hewlett-Packard (Texas Instruments) - technology

- IBM (Burroughs) - technology

- Johnson & Johnson (Bristol-Myers Squibb) - pharmaceuticals, medical devices, consumer health care

- Marriott (Howard Johnson) - hospitality

- Merck (Pfizer) - chemicals, pharmaceuticals

- Motorola (Zenith) - telecommunications

- Nordstrom (Melville) - retail

- Philip Morris (RJR Nabisco) - tobacco

- Procter & Gamble (Colgate) - consumer goods

- Sony (Kenwood) - conglomerate (electronics, gaming consoles, media)

- Walmart (Ames) - retail and wholesale

- Walt Disney (Columbia) - entertainment

Once the research team had their list, they closely examined the companies’ history and evolution, conducted a comparative analysis to find principles and patterns of success, and came up with key concepts that may be useful to those building companies in the present day. These concepts debunked twelve myths about what it takes to build a visionary company.

Myth 1: A Great Company Starts From a Great Idea

Business schools espouse that you need a great idea backed by a solid marketing plan before starting a company, but visionary companies show that this simply isn’t true. Out of the 18 visionary companies, only three had a specific product or service in mind when they began: Johnson & Johnson, General Electric, and Ford. All the others tried one thing after another, stumbling before finding their footing and eventually becoming a great success.

- For example, Hewlett-Packard (HP) began in 1937 without a product. Bill Hewlett and David Packard used their engineering backgrounds to create various contraptions, from bowling lanes to telescopes to urinals, many of which didn’t produce great results. They didn’t let their failures dissuade them—they kept creating and experimenting until they acquired profitable war contracts in the 1940s.

A great idea shouldn’t be the be-all and end-all of a company. Every product, no matter how innovative, will eventually become obsolete. If you pin organizational success to that one great idea, then you won’t have what it takes to find lasting success.

This means that when building a visionary company, the product isn’t the point—the company is. You can only build an enduring company if you never give up, even if your products keep failing. Instead of focusing all your attention on designing a great product, shift your focus to designing a great organization.

Myth 2: Behind Every Visionary Company Is a Larger-Than-Life Leader

A high-profile leader who fits the mold of the superstar CEO isn’t necessary to build a visionary company—but good leadership is. A company won’t last long with one mediocre head after another.

Though their personalities vary from larger-than-life and charismatic to quiet and unassuming, visionary leaders are driven by a common purpose: They recognize that their job is to build something that will endure even after they’re gone. They know that, just as one great idea and one great product can become obsolete, so too can a great leader. Rather than being driven by making one product successful or building their own personal brand, they focus on building an organization that lasts.

What These Two Myths Tell Us

These first two debunked myths—that one great idea and a charismatic leader are required to build a great company—reveal a distinguishing characteristic of visionary companies: They are clock builders, not time tellers:

- Time tellers have the amazing ability to tell the exact time by looking up at the sky.

- Clock builders make a clock that can tell everyone the time, even after they’re gone.

Once you shift your focus from time telling to clock building, you’ll be better able to understand that putting systems in place that create repeated, enduring success is one of the key concepts behind building a company that lasts.

Myth 3: You Can’t Have It All

Visionary companies don’t allow themselves to be ruled by or—the view that you must choose between seemingly contradictory choices A or B (for example, change or stability, low cost or high quality, investment in the long-term or success in the short-term). Instead, they debunk the myth that you can’t have it all by believing in and—they figure out a way to have both A and B. It’s like the Chinese yin-yang symbol, where black and white don’t blend into gray but come together in perfect harmony.

Myth 4: Visionary Companies Are Profit-Driven

Visionary companies put the power of the and into practice when it comes to profit. They are both pragmatic (bringing in profit) and idealistic (driven by something more than profit), and they do this by remaining true to their core philosophy.

For visionary companies, profitability is an objective, but not the primary objective—that is, without profit, visionary companies can’t exist, but it’s not why they exist. This paradox of pursuing both profit and broader aims is made possible by the company’s core philosophy: a set of guiding principles that remain steadfast through generations of changing leadership and processes. They’re an integral part of building a clock.

It’s not always an easy road, and visionary companies don’t have a perfect record of adhering to their values. But compared to their competitors, they have put in much more effort to articulate and adhere to their core philosophies, through good times and bad.

Myth 5: There Is Only One “Right” Way to Do Things

Core philosophies aren’t universal. While some visionary companies share common guiding principles (for example, customer service or product innovation), there isn’t one set of principles that’s common across all visionary companies. What matters isn’t what a core philosophy says; what matters is how strongly and consistently the organization adheres to it.

A core philosophy is made up of two elements:

- Core values: a set of guiding principles that you stick to no matter what

- Purpose: your reason for being, beyond mere profit

A core philosophy should be a reflection of what you believe in, not something you think you should believe in. When trying to put the ideology into words, first identify your core values in a clear and concise way, then limit them to those that you know you’ll stick to, no matter what happens. Then articulate your purpose by asking, “Besides profit, what drives the company?” From there, you can come up with an enduring core philosophy that can guide you for decades.

Myth 6: Change Is Constant

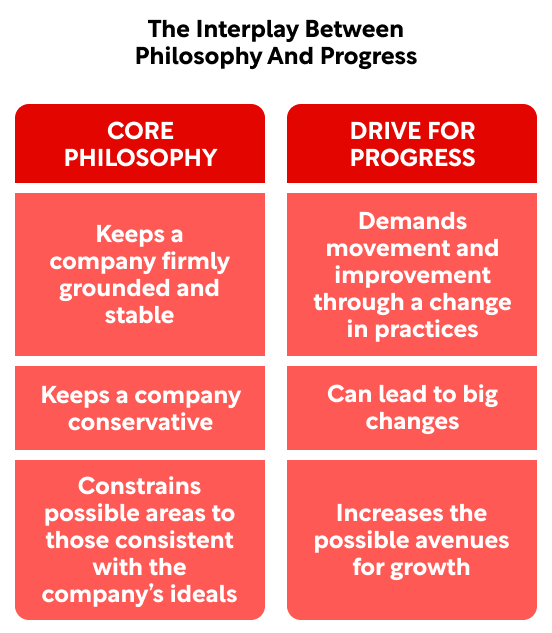

The research debunks the myth that visionary companies are constantly changing at a high-speed pace. While they do have an incredible drive for progress, they don’t evolve at the expense of their core ideals. This is the very essence of a visionary company: They employ the power of the and to preserve the core and stimulate progress.

Visionary companies are crucially able to distinguish between a core philosophy—timeless, unchanging principles—and non-core practices—manifestations of this core philosophy that change constantly to keep up with an ever-evolving world.

- For example, Boeing’s core philosophy is, “Being on the leading edge of aviation,” while their non-core practice is making jumbo jets. If they stop making jumbo jets and start making flying cars, they would be changing a non-core practice while still adhering to their core ideology.

When you mistake a non-core practice that can be changed for a core ideal that can’t be changed, you remain stagnant and will eventually fall behind as the world passes you by. It’s thus important to maintain the yin of preserving the core alongside the yang of stimulating progress. A visionary company uses a core philosophy to define the boundaries between what they can and can’t do, then use a drive for progress to fly within those lines.

Myth 7: Visionary Companies Are Ultra-Conservative

The research revealed that one of the ways visionary companies stimulate progress is not conservative: They set daring, seemingly impossible goals, or what Collins and Porras coined Big Hairy Audacious Goals (BHAGs, pronounced bee-hags). These BHAGs typically take 10 to 30 years to achieve and only have a 50 to 70 percent probability of success—but visionary companies see them as eminently doable.

There are different types of BHAGs: Ambition BHAGs can be quantitative (“become a $1 billion company by X”) or qualitative targets; challenger BHAGs focus on beating the competition; icon BHAGs seek to emulate established players; and refresher BHAGs are big changes that are great for old or big organizations that need a shot in the arm.

When coming up with your BHAG:

- Be precise about the language that you use so that it’s easy to understand and unambiguous.

- Reflect on your goal’s audacity and ensure that it pushes you out of your comfort zone.

- Check your goal’s alignment with your core philosophy.

Increase your chances of achieving your BHAG by fully committing to it, being driven by something greater than profit, and building it into the organization so that it transcends any disruption such as a change in leadership. Lastly, it’s essential that you keep setting more BHAGs even as you cross others off your list so that you don’t become complacent.

Myth 8: Anyone Can Fit Right Into a Visionary Company

For many people, working at a visionary company is the dream. But, as the research reveals, not everyone can work at these dream companies; some people just don’t fit in. This is because visionary companies want to preserve their core philosophy and thus make sure that everyone in the company is compatible with their ideals.

Visionary companies are so single-minded when it comes to preserving their core that they’re almost cult-like. In their quest to ensure that everyone in the company is on the same page, they’ve demonstrated the following cult-like practices and characteristics:

- Alignment: Visionary companies have a tough screening process and systems—rewards for actions that adhere to the core philosophy and penalties for non-adherence—to ensure that new hires fit seamlessly into the organization.

- Indoctrination: Visionary companies thoroughly immerse new employees in the core philosophy. They have orientation seminars and even full-blown “universities” to teach the company’s history, values, and traditions.

- Exclusivity: Visionary companies want their employees to feel like they are part of a special, elite group. They encourage their workers to socialize among themselves and not with outsiders. For example, IBM took “employee socialization” to a new level: The company managed country clubs where IBMers could mix and mingle exclusively with other IBMers.

These cult-like practices may seem like an almost unhealthy desire to control their people. But having these practices in place not only maintains the core but also enables companies to entrust their employees with operational autonomy. When they see that employees embody what the company is all about, visionary companies give them the wings to fly.

Myth 9: Visionary Companies Carefully Plan Everything

The authors debunk the myth that visionary companies’ success is wholly a result of deliberate planning. While visionary companies are strategic planners, some of them reached new heights through something akin to Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory: Species evolved over time through a process of “variation,” changing to adapt to their environment, and then “selection,” wherein only the strongest variants survive.

While visionary companies do a fair amount of strategic planning, such as setting BHAGs, they also make use of their own process of variation and selection, keeping the best results of their experiments and making the most of opportunities that come their way.

If you want to stimulate evolutionary progress, you have to make room for unplanned variation and allow your people to experiment and get creative. You have to act quickly and seize opportunities that come your way. Accept that mistakes are all part of the process—evolution isn’t perfect; failed experiments are an inherent part of it, just as weak mutations don’t survive as a species evolves.

- For example, Johnson & Johnson had successful experiments like Band-Aids, but also had many failed experiments, such as kola stimulants, ibuprofen pain relievers, and colored casts that stained hospital linens.

Myth 10: Hiring CEOs From Outside Can Revitalize a Company

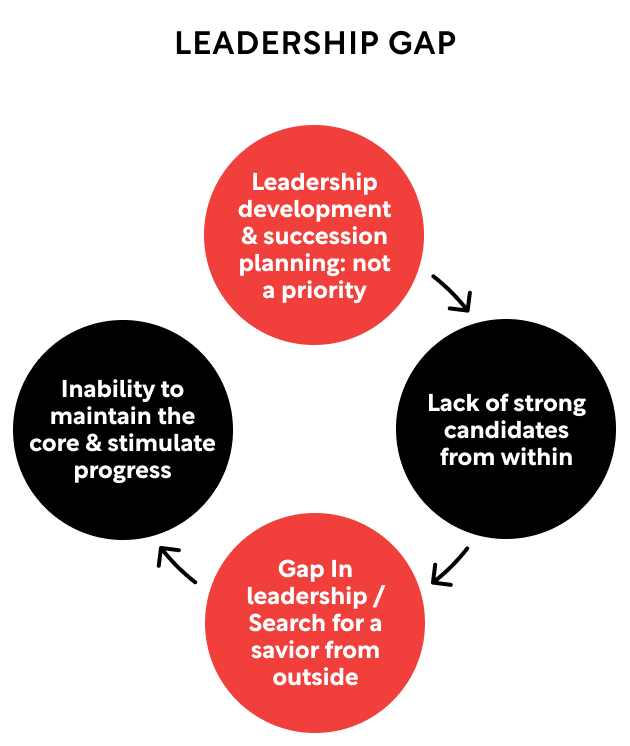

Sometimes, flagging companies look to an outsider to be their savior. But visionary companies hardly ever look outside; in fact, within the era of study, they only hired 3.5 percent of their 113 chief executives from outside, versus comparison companies’ 22.1 percent out of 140. That’s because visionary companies ensure that they have a leadership continuity loop:

- They develop leaders and come up with a succession plan. Visionary companies have formal management development programs to identify and train top managerial talent in the organization. Leaders also put a lot of thought into succession, sometimes planning years in advance.

- They have a list of strong internal candidates. Visionary companies have a culture of developing and training leaders through intensive management training programs. As a result, the companies often have a number of capable candidates who are ready to take on a leadership role when needed.

- They ensure continuous excellent leadership from within. Those who find themselves in leadership roles at visionary companies then keep the cycle going by planning for their successor.

These three elements form a never-ending loop that allows the company to maintain the core while stimulating progress. When any of these elements is missing, a company ends up with a leadership gap. Without good people leading the way, a company may find itself stuck, unsure of how to move forward. They may then scramble for a replacement from outside, hoping this savior will give the company some much-needed stimulation. However, an outsider who isn’t aligned with the company’s core philosophy may steer the company in a direction that may be damaging to the company.

If you’re a CEO or a member of top management, you should identify, train, and promote top managerial talent. Formulate a long-range succession plan so that passing the torch from one generation to the next will be seamless. If you’re a manager, think about developing leaders and coming up with a succession plan for your department or group. If you’re an entrepreneur, think long-term—start thinking about how your business can endure from generation to generation, long after you’re gone.

Myth 11: Visionary Companies Are Relentless Versus the Competition

Visionary companies aren’t obsessed with doing better than their competitors; instead, they’re primarily focused on beating themselves. At no point do visionary companies ever think that they’ve reached the finish line—continuous improvement is a part of who they are, and so they always demand more of themselves.

Visionary companies implement policies with teeth to ensure that they keep performing better than they did the year before. In particular, they do two things:

- Seed discomfort. Visionary companies want their people to feel discontented with their accomplishments because it pushes them to strive for more. To create motivational discontent, visionary companies use various tactics. Some examples of these tactics are internal competitions between brands, forced innovation by getting rid of profitable product lines, and pooled rankings among employees.

- Think long-term. Visionary companies think 50 years into the future and make long-term investments in several areas: new property, plants, and equipment; research and development; new management methods, industry practices, and technology; and human capital. They never sacrifice long-term goals for the sake of short-term profit.

The quest for self-improvement is never-ending, because success is never final. Even when a company is at the top, there’s no guarantee that they’ll stay there.

Myth 12: Vision Statements Are an Integral Part of Success

Having a vision statement can be useful, but it’s only the first step. Contrary to the myth, a vision statement doesn’t guarantee greatness; the real work is in bringing the vision to life. Visionary companies try to bring the vision to life by incorporating their core philosophy into everything they do and, most importantly, making sure their methods are aligned with each other.

Alignment means that everything a company does and every element reinforce each other. When a company doesn’t have alignment, constantly opposing forces significantly hinder their progress.

Seeking alignment is a tricky, never-ending process, but these actions help:

- Take a big-picture approach. Visionary companies use a comprehensive, carefully thought-out, and consistent system to achieve the yin and yang of maintaining the core and stimulating progress. You can’t take a single element—a core ideology, BHAGs, evolution, a cult-like culture, management development—and create a masterpiece. It takes all of these things working together.

- Pay attention to details. While a big picture is nice to look at, the small details are vital. Employees have a greater drive to achieve the vision when they see it consistently in the small, day-to-day signals and cues.

- Put together mechanisms that reinforce each other. Visionary companies don’t introduce anything arbitrarily; each element works in concert with others. Visionary companies put together mechanisms that reinforce each other to deliver a clear, consistent message.

- Be guided by your core. Visionary companies don’t let trends dictate their actions; rather than asking if a practice is “good” or “bad,” they ask if it’s something that’s aligned with their core.

- Eliminate misalignments. While your core philosophy should remain sacred, everything else can evolve. When a company lets their non-core practices evolve, it’s easy to allow practices and policies that push the company away from its core philosophy or slow down progress. Stay vigilant and correct these misalignments.

- Come up with new methods. Some visionary companies use more BHAGs, others use more mechanisms of discontent. You can use a combination of ideas from this book to see what works for your company, but you don’t have to stop there. You can invent new ways of maintaining the core and stimulating progress—as long as they’re true to your core philosophy.

Taking all the key concepts together, the four key concepts behind building a visionary company are:

- Focus on clock building, not time telling.

- Tap into the “power of the and.”

- Embrace the yin and yang of maintaining the core and stimulating progress.

- Keep everything aligned.

Four concepts sound simple enough. Simple doesn’t mean easy, but with this framework, you can start applying these concepts, no matter who you are. Apply them to your organization, your fledgling business, or your team. Amplify your efforts by helping others around you understand the concepts and take them to heart. And always remember that enduring greatness, though challenging, is within your reach.

Shortform Introduction

In Built to Last, bestselling author Jim Collins and Stanford professor Jerry I. Porras embarked on a six-year research project to 1) identify the characteristics that distinguished the very best companies, and 2) use these insights to create a framework for those who want to build visionary companies of their own. To this end, the authors identified and analyzed 18 visionary companies that performed exceptionally well over a long period of time.

The book became an instant classic. However, it’s important to note that it was published in 1994. Since then, some of the visionary companies have faltered.

- For example, Motorola has seen its market share dwindle with newer or revitalized companies like Samsung and Apple pulling ahead. Ford is once again behind General Motors in terms of market share. Nordstrom has closed many of its stores.

It’s possible that many of the companies were greatly affected by the advent of the internet and other huge shifts in technology over the last 25 years. It’s also possible that the companies have become less successful because they veered away from the concepts presented in this book. We at Shortform won’t discuss whether the changes in the visionary companies’ status undermine the authors’ research findings. We do believe that the authors’ findings are still an insightful look at the keys behind companies’ enduring success, even if it was during a previous era.

Chapter 1: What Makes a Company “Visionary”?

Many enterprises come and go, but visionary companies endure for generations. These companies are the gold standard in their respective industries because they’ve prospered for decades and at the hands of many different leaders. They’ve become household names, ingraining themselves into our collective psyche—it’s hard to imagine a world without their products, from Band-Aids to Post-it Notes to Mickey Mouse.

But what is the key to these companies’ longevity and tremendous success? Bestselling author Jim Collins and Stanford professor Jerry I. Porras embarked on a six-year research project to answer this question and give practical advice for those who want to build a company that lasts.

Narrowing Down the List of Companies

The authors’ primary objectives for the research project were 1) to identify the characteristics that distinguished the very best companies, and 2) to use these insights to create a framework for those who want to build visionary companies of their own.

The authors came up with their list by surveying CEOs across numerous enterprises of various sizes, industries, and geographic locations, asking them to identify the companies they considered to be visionary. From there, the researchers narrowed the list down to the 20 most-frequently mentioned companies, then eliminated those founded after 1950. (Their reasoning: Companies founded before 1950 have proven that their success wasn’t a fluke due to one leader or one great idea.)

The researchers then identified a “comparison company” for each of the visionary companies—that is, a company that was founded at around the same time, had the same founding products and markets, and was also highly successful, but not as successful as its comparative visionary company.

The final 18 visionary companies are listed below. Their comparison companies are in parentheses.

- 3M (Norton) - consumer products

- American Express (Wells Fargo) - financial and travel services

- Boeing (McDonnell Douglas) - aviation

- Citicorp (Chase Manhattan) - banking

- Ford (GM) - automotive

- General Electric (Westinghouse) - conglomerate (power, energy, aviation, health care)

- Hewlett-Packard (Texas Instruments) - technology

- IBM (Burroughs) - technology

- Johnson & Johnson (Bristol-Myers Squibb) - pharmaceuticals, medical devices, consumer health care

- Marriott (Howard Johnson) - hospitality

- Merck (Pfizer) - chemicals, pharmaceuticals

- Motorola (Zenith) - telecommunications

- Nordstrom (Melville) - retail

- Philip Morris (RJR Nabisco) - tobacco

- Procter & Gamble (Colgate) - consumer goods

- Sony (Kenwood) - conglomerate (electronics, gaming consoles, media)

- Walmart (Ames) - retail and wholesale

- Walt Disney (Columbia) - entertainment

They closely examined each company’s history and evolution, conducted a comparative analysis, identified key concepts that led to the visionary companies’ success over their competition, and created a framework for those who want to build visionary companies. They then further refined their framework by asking 30 organizations to test it in real-world situations and give feedback.

Visionary Company Myths We’ll Debunk

Their research findings debunked 12 myths about visionary companies. We’ll discuss each in detail in the following chapters:

- Myth 1: A great company starts from a great idea. Surprisingly, some visionary companies started without anything specific in mind. Some had a number of misfires in the beginning and took some time to hit their stride.

- Myth 2: Behind every visionary company is a larger-than-life, visionary leader. The research revealed that leaders come in all shapes and forms—not all of them have the charisma and big personality you might expect from a CEO of a high-flying corporation. What they do have in common is that they’re more invested in building the company than in building their own brand.

- Myth 3: You can’t have it all. Visionary companies don’t believe that they have to make a choice between two seemingly paradoxical goals. Instead of being ruled by or (for example, stability or progress), they believe in and (stability and progress).

- Myth 4: Visionary companies are profit-driven. The research revealed that visionary companies aren’t singularly focused on profit. They focus on profit and their values and purpose equally.

- Myth 5: There is only one way to do things and one set of values to follow. The research found that core values aren’t one-size-fits-all for visionary companies—each had its own priorities and way of doing things.

- Myth 6: Change is constant. The research found that while visionary companies do relentlessly pursue progress, they also rigorously adhere to their ideals and values.

- Myth 7: Visionary companies are ultra-conservative. The research found that, far from playing it safe all the time, visionary companies aren’t afraid to make big moves (what the authors call “Big Hairy Audacious Goals”).

- Myth 8: Anyone can fit right into a visionary company. While many people dream of working for these companies, not everyone is a good fit. Visionary companies are almost cult-like when it comes to what they stand for, and some people just can’t get on board.

- Myth 9: Visionary companies carefully plan everything. On the contrary, they leave plenty of room to adapt. They sometimes even rely on opportunism or accidents.

- Myth 10: Hiring CEOs from outside can revitalize a company. Visionary companies love their own. They rely largely on talent and new ideas from within the organization.

- Myth 11: Visionary companies are relentless when it comes to competition. Visionary companies see themselves as their biggest competition. They believe that there is always room for improvement.

- Myth 12: Vision statements are an integral part of success. A statement doesn’t do the work for a visionary company. It can serve as a useful guide, but it’s just a small part of the process of building something that lasts.

Chapter 2: A Change in Focus

In this chapter, we’ll examine two myths of visionary companies. First, we’ll discuss and debunk the myth that a company requires one great idea to get started. Then, we’ll look at why visionary companies don’t need a high-profile, charismatic leader to achieve enduring greatness.

A Big Idea Isn’t Everything

Business schools espouse that you need a great idea backed by a solid marketing plan before starting a company. But visionary companies show that this simply isn’t true.

Out of the 18 visionary companies, only three had a specific product or service in mind when they began: Johnson & Johnson, General Electric, and Ford. All the others tried one thing after another, getting both hits and misses and refining their offerings along the way. Many limped and stumbled before finding their footing and eventually becoming a great success.

- For example, Hewlett-Packard (HP) began in 1937 without a product. Bill Hewlett and David Packard used their engineering backgrounds to create various contraptions, from bowling lanes to telescopes to urinals, many of which didn’t produce great results. They didn’t let their failures dissuade them—kept creating and experimenting until they acquired profitable war contracts in the 1940s.

The Product Isn’t the Point

A great idea shouldn’t be the be-all and end-all of a company, and is actually detrimental in three ways:

- If it fails, you might get discouraged and abandon the company altogether.

- If it succeeds, you might become too attached to it, ignoring other avenues for growth.

- Any product, no matter how innovative, will eventually become obsolete. If you pin organizational success to that one great idea, then you won’t have what it takes to find lasting success.

When building a visionary company, the product isn’t the point—the company is. You can only build an enduring company if you never give up, even if your products keep failing. Instead of focusing all your attention on designing a great product, shift your focus to designing a great organization.

- For example, General Electric (GE) used Edison’s direct current system, which proved inferior to their competitor Westinghouse’s alternating current system. But one product didn’t dictate GE’s fate. They established the General Electric Research Lab, which created many more products that helped propel GE to greatness.

A Superstar CEO Isn’t Everything

Companies don’t become visionary through one product—nor through one charismatic leader. While a high-profile leader who fits the mold of the superstar CEO isn’t necessary, good leadership is. After all, it’s highly unlikely for a company to last long with one mediocre head after another.

What Makes a Good Visionary Leader?

Though their personalities vary from larger-than-life and charismatic to quiet and unassuming, visionary leaders are driven by a common purpose: They recognize that their job is to build something that will endure even after they’re gone. They know that, just as one great idea and one great product can become obsolete, so too can a great leader. Rather than being driven by making one product successful or building their own personal brand, they focus on building an organization that lasts.

- For example, William McKnight didn’t fit the usual image of a superstar CEO. By all accounts, he was modest, quiet, and thoughtful. He was more interested in leaving behind an enduring company than in being mentioned in history books. He was at the helm of 3M for over five decades as general manager, chief executive, and then chairman. Not a lot of people know his name, but people the world over know 3M, even long after McKnight’s time.

(Shortform note: Read our summary of The 5 Levels of Leadership to learn how to become a strong leader that builds a legacy instead of a brand.)

A Paradigm Shift: From Time Telling to Clock Building

The fact that visionary companies don’t rely on one great idea or one superstar CEO represents one of their distinguishing characteristics: Rather than focusing on “time telling,” they focus on “clock building.”

- Time telling: You rely on one person’s unique ability to tell the exact time by looking at the sky. Once that person is gone, everyone else will be lost. Letting one great idea or leader carry a whole company is time telling.

- Clock building: You make a “clock,” or system, that can tell everyone the time, even after you’re gone. Creating an innovative company and strengthening your leadership culture so that the company will continue to thrive is clock building.

For example, Walmart’s Sam Walton had the stereotypical superstar CEO charisma, but also had an essential characteristic of a visionary leader: He was an architect. He empowered people to run their departments, gave incentives to encourage creativity and productivity, and democratized the sharing of ideas. He also groomed his successor to ensure that Walmart stayed true to what it stood for.

Once you shift your focus from time telling to clock building, you’ll be better able to understand the concepts in the succeeding chapters.

Exercise: Become a Clock Builder

Clock building seems like a daunting task, so start small by determining how processes you’re already involved in can continue to work without you.

List all of your responsibilities in your organization. Of these responsibilities, which ones would create a bottleneck in your organization’s workflow if you were to get promoted or go on leave?

Choose one of these responsibilities. Describe how being absent or otherwise unable to fulfill this responsibility can affect the overall organizational workflow.

What are two or three steps you can take today to ensure that your absence won’t cause a disruption in your organization?

Chapter 3: Driven by More Than Profit

In this chapter, we’ll debunk three intertwined myths: first, that visionary companies can’t have it all and need to make a choice between two seemingly paradoxical goals; second, that they’re purely profit-driven; and third, that they all do things the same way and follow one set of values.

Or Versus And

One of the central concepts of visionary companies debunks the myth that they must choose between paradoxical goals: They don’t put limits on themselves by being ruled by or—that is, the view that you must choose between seemingly contradictory choices A or B.

- For example, the idea that a company can have change or stability, go for low cost or high quality, or invest in the long-term or do well in the short-term.

Instead, they believe in the power of and—that is, they figure out a way to have both A and B. It’s like the Chinese yin-yang symbol, where black and white don’t blend into gray but come together in perfect harmony.

The Importance of a Core Philosophy

Not being ruled by or and believing in the power of and means that companies are able to be profitable and stick to their ideals. This debunks another myth, one commonly taught in business schools: that a company’s goal is to maximize profits and keep shareholders happy.

For visionary companies, profitability is just one of the objectives, but not the primary objective. Without profit, visionary companies can’t exist, but it’s not why they exist. This paradox of pursuing both profit and broader aims is made possible by a core philosophy: a company’s guiding principles that have rarely changed through generations of changing leadership and that are an integral part of building a clock.

Why Core Philosophies Are So Important to Visionary Companies

While some may dismiss core philosophies as nothing more than words, there are two reasons they’re held in significant esteem in visionary companies:

- According to social psychology, people are more likely to follow through with something when they declare it in public, so for visionary companies to have a core philosophy already sets the stage for them to act in alignment with the philosophy.

- When visionary companies have a concrete core philosophy, they can make sure everyone in the organization is aligned with it. (In the following chapters, we’ll cover how companies ensure this.)

Example: Johnson & Johnson’s Tylenol Crisis Recovery

Johnson & Johnson’s core ideology is evident in their company credo, which states the hierarchy of five responsibilities: First, to the people who use their products; second, to their employees; third, to their management; fourth, to the communities in which they live; and lastly, to their stockholders.

J&J’s adherence to their credo was exemplified in the Tylenol crisis of 1982. Seven people in Chicago died as a result of Tylenol bottles that had been tampered with. J&J responded by thinking of their consumers first: They recalled all the Tylenol capsules from the entire country, which cost them $100 million. They also launched a massive communication effort to keep the public informed. Despite losing $100 million, they profited in the long run, earning the public’s trust and becoming one of the 18 visionary companies.

In contrast, when comparison company Bristol-Myers had a similar problem with Excedrin tablets in Denver, they only recalled tablets from Colorado and didn’t communicate the issue to the public. They were entirely focused on their bottom line—and yet they haven’t profited nearly as much as J&J.

(Shortform note: Read our guide to Predictably Irrational to learn more about why J&J’s response to the Tylenol crisis increased brand trust.)

The Components of a Core Philosophy

Establishing a core philosophy is one of the fundamental steps for building a visionary company. If you’re not a CEO, you can articulate it for your own department or division, guided by your company’s core philosophy, if it already has one. If you’re an entrepreneur in the middle of getting your business off the ground, try not to put off this exercise for too long—the sooner you can figure it out, the better.

Your core philosophy is made up of your core values (a set of guiding principles that you stick to no matter what) plus your purpose (your reason for being, beyond mere profit). To better spell out your core philosophy, start from a place of authenticity. While your values and your purpose may be similar to those of other companies, they should be a reflection of what you truly believe in..

Identify Your Core Values

When formulating your core philosophy, ask people to nominate five to seven individuals from your organization who they think are credible, competent individuals who are exemplars of the values of the organization. Then, gather the nominated individuals to discuss and identify the core values, making sure that they:

- Make it clear and concise. Figure out what’s important to you, then state it in a simple and straightforward manner. For example, Wal-Mart emphasizes putting the customer ahead of everything else, and HP emphasizes respect and concern for the individual.

- Limit the number. Visionary companies have between three and six core values. If you find that you have more than six, strip them down to the ones that are fundamental to your company and that will stand the test of time. Determine which ones you want to stick to, for better or for worse. You can cross out the ones you can change or get rid of if circumstances change—it doesn’t mean they’re not important. It only means they aren’t core values.

Identify Your Purpose

Then move on to the company’s purpose, which the authors believe is the more important component to guiding and inspiring an organization. The research found that some visionary companies are more explicit when it comes to stating their purpose, while others are more informal. Identify yours by:

1. Asking, “Why are we here?” What drives you beyond profitability? Get to your fundamental purpose by starting off with a descriptive statement (“We provide X services”) and then asking, “Why is this important?” five times. This repetition helps shrink a large, vague idea down to your fundamental purpose.

- For example, a cement company’s descriptive statement might be, “We manufacture cement.” That mundane descriptive statement can turn into something as inspiring as, “We make people’s lives better by helping build high-quality man-made structures.”

2. Going beyond keeping shareholders happy. Increasing shareholder wealth is the go-to purpose for organizations that haven’t yet determined their true core purpose. It’s a weak purpose that isn’t enough to get people excited. To go beyond mere profit, answer: If the company didn’t have to worry about making money, what would motivate you to keep working anyway?

3. Ensuring that it’s something the company can keep pursuing, not just something to check off a list. A purpose isn’t a goal that you can attain but the driving force behind what you do. You can change your goals and move into other business areas while being guided by the same purpose.

- For example, Marriott’s purpose is to make people feel at home. This began when they opened their first A&W root beer stand, where they gave people a place to quench their thirst during hot summers, and guided them as they expanded to other ventures like hotels.

Different Companies, Different Philosophies

Don’t be alarmed if your core philosophy looks nothing like those of visionary companies. In fact, Collins and Porras’s research also debunks the myth that all visionary companies are guided by the same core philosophy. While some companies share common themes—J&J and Wal-Mart are customer-centric, Ford and Disney are product-centric—there is no single theme that’s common across all visionary companies. What matters isn’t what a core ideology says; what matters is how strongly and consistently the organization adheres to it.

- For example, Philip Morris adamantly, even defiantly, stuck to their ideology consisting of hard work, continued self-improvement, and freedom—people have the right and the choice to smoke. While advocating smoking may not be palatable to outsiders, those within Philip Morris lived and breathed the culture. Employees brought home boxes of cigarettes along with their paychecks.

It’s not always an easy road—it’s a challenge to try to be both pragmatic and idealistic. And visionary companies don’t have a perfect record of adhering to their values, as a handful of them have had some ethical slip-ups at some point. But compared to their competitors, they have put much more effort into articulating and adhering to their core philosophies, through good times and bad.

Exercise: Determine Your Core Philosophy

Knowing your core values and your purpose is fundamental to building a visionary company because it gives you a philosophy that will guide all your decisions. If you’re a CEO, you can form your group of five to seven people to articulate your core. If you’re a non-CEO, you can do this for your group, department, or division. If you’re an entrepreneur, you can verbalize it now and use it to guide you as you grow your business.

List down your core values—what’s most important to you, what brings you fulfillment. You can write as many as you can think of, no need to limit yourself at this point. (For example, reliability, consistency, efficiency, and so on.)

Which of these values would make a solid foundation for an organization, even 100 years into the future? Explain your reasoning.

Which core values should someone have in order to fit in with your organization? Explain your reasoning.

Determine your purpose: Start with a descriptive statement of your business, then ask “Why is this important?” five times. Write out your five responses and the final purpose they reveal.

Chapter 4: How Visionary Companies Stay Grounded While Moving Forward

This chapter debunks the myth that visionary companies are constantly changing. While they do have an incredible drive for progress and innovation—they don’t evolve at the expense of their core ideals. And this is the very essence of a visionary company: They use the power of and to maintain the core and stimulate progress.

The Difference Between Core Philosophy and Non-Core Practices

While a core philosophy is fundamental, visionary companies don’t thrive by their ideals alone. If you don’t pair your guiding principles with action and innovation, you’ll be left behind in a world that’s constantly on the move. The key to moving forward is to stick to your core ideals while changing only non-core practices.

A core philosophy is an unwavering set of guiding principles, while a non-core practice is a new product line, a new organization structure, or even a new office layout—anything that can change and evolve as long as it aligns with the core philosophy.

- For example, Boeing’s core ideology is “Being on the leading edge of aviation,” while their non-core practice is making jumbo jets. If they stop making jumbo jets and start making flying cars, they would be changing a non-core practice while still adhering to their core ideology.

Stimulate Progress

When you mistake a non-core practice that can (and should) be changed for a core ideal that can’t be changed, you remain stagnant and will eventually fall behind as the world passes you by. It’s thus important to maintain the yin of maintaining the core alongside the yang of stimulating progress. A visionary company uses a core ideology to define the boundaries between what they can and can’t do, then use a drive for progress to fly within those lines.

Companies have a relentless drive for progress that isn’t influenced by external factors, like what their competition is doing or what industry pundits think they should be doing. Instead, they serve as their own biggest critics, constantly evaluating their non-core practices to see what can be improved.

- For example, 3M doesn’t wait to see what competitors are doing before taking action. Through experimentation and innovation to meet needs that consumers didn’t even think they had, they came up with ingenious products like Scotch tape and Post-it Notes.

The Key Takeaway

The concept of maintaining the core while stimulating progress is the foundation of the next chapters, which discuss practical, actionable steps toward attaining visionary status:

- Commit to challenging, even risky, goals or what the authors call Big Hairy Audacious Goals (stimulates progress)

- Foster a cult-like workplace culture that’s suited only to those who are aligned with the core ideology (maintains the core)

- Keep experimenting (stimulates progress)

- Promote from within (maintains the core)

- Never settle for “good enough” and keep striving to do better (stimulates progress)

Chapter 5: Commit to Big Hairy Audacious Goals

In this chapter, we’ll discuss and debunk the myth that successful companies are conservative and prefer not to make bold moves.

The research revealed that far from being overly cautious, visionary companies in fact set risky, progress-stimulating goals—what Collins and Porras have coined Big Hairy Audacious Goals (or BHAGs, pronounced bee-hags). BHAGs are goals that take you out of your comfort zone and require a strong commitment to see them through. They typically take 10 to 30 years to achieve and only have a 50- to 70-percent probability of success, but you should be able to look at them and believe that you can achieve them.

If you’re an entrepreneur, then you’re no stranger to BHAGs, as getting a business off the ground is already a BHAG in itself. If you work for a company, you can pursue BHAGs at any level, whether it’s within your team or within the entire corporation.

- For example, if you’re a new hire in the accounting department of a big corporation, your BHAG might be to become the vice president of finance within 15 years.

Visionary companies use four different types of BHAGs:

- Ambition: This can be a quantitative or qualitative target that you want to reach. For example, a fledgling fast-food restaurant might have a BHAG of selling 100 million burgers within 10 years.

- Challenger: This focuses on beating the competition, a specific strong player in the industry. For example, a yoga wear company’s BHAG might be to unseat Lululemon as the most recognizable brand in the industry.

- Icon: This focuses on emulating a successful company, which may or may not be in the same industry. It’s particularly great for new businesses. For example, a new manufacturing company’s BHAG might be to become as globally recognizable as 3M.

- Refresher: This might be a shift in the product offerings or a revamp of a company’s image. It’s especially effective for old or big organizations. For example, a company known for cheap, low-quality cosmetics might set a BHAG to become a respected player in the skincare industry.

Characteristics of a BHAG

A BHAG isn’t a vague and verbose mission statement that no one can remember—it’s clear, compelling, challenging, and risky, while also reinforcing the core ideology. There are three steps to coming up with your BHAG.

1) Clarify the Language Around Your Goal

It should be a precise goal that’s easy to understand, not a meaningless statement that needs explanation. “Land a man on the moon” is a much more direct and exciting goal to shoot for than, “Improve the space program.” It paints a compelling picture of the finish line, inspires people, and ignites team spirit. It creates momentum and galvanizes people into action.

(Shortform note: Read our guide to Switch to learn more about the changemaking power of painting a vivid picture of your destination.)

2) Reflect on Your Goal’s Audacity

If it’s easy to achieve, then it’s not big, hairy, and audacious. A BHAG should push your company out of its comfort zone, because that’s where growth and progress happens. You’ll need a great deal—even an unreasonable amount—of confidence that you can do something that outsiders may deem absurd or impossible.

3) Check Your Goal’s Alignment With Your Core Philosophy

Just as visionary companies don’t live on core philosophy alone, neither do they rely solely on BHAGs for long-term success. They pursue only those BHAGs that reinforce their ideals. While core philosophy serves as a solid, stable platform from which to launch their BHAGs, the BHAGs serve as a non-core practice that brings the ideology to life. Again, they use the power of and to both maintain the core and stimulate progress.

- Example: Boeing stayed true to their core philosophy of being pioneers and innovators in aviation, even as they set new BHAGs and built one ambitious plane after another.

An excellent example of a BHAG is U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s goal in 1961 to put a man on the moon within the decade. The pronouncement was clear and ambiguous, expressing a direct and exciting goal. It was seemingly outrageous, with a 50-50 chance of success. And it aligned with JFK’s mission to get America moving speedily forward again after a lethargic decade.

How to Ensure Your BHAG’s Success

Achieving a BHAG is extremely challenging and takes extraordinary drive and commitment. There are four ways to increase your chances of accomplishing your BHAG.

1. Fully commit to it. It’s not enough to have a BHAG; you also need to be willing to do whatever it takes to achieve it.

- For example, in 1965, Boeing put everything on the line to develop the 747 jumbo jet—Chairman William Allen expressed that he was willing to use all of the company’s resources to do so. This BHAG was nearly the company’s downfall at first—Boeing had to lay off 86,000 people over three years due to slow sales, but they didn’t give up. The 747 eventually became the flagship jumbo jet of the airline industry.

(Shortform note: In Great by Choice, Collins introduces the concept of “leading above the Death Line,” which means avoiding big risks that can kill a company. This seems to run counter to BHAGs. He addresses this and emphasizes the importance of and: Companies should pursue BHAGs and stay above the Death Line. Read our full summary of Great by Choice.)

2. Look beyond the money. As we’ve discussed, visionary companies are driven by something greater than profit. They are driven by a compelling urge to keep pushing the bounds of impossibility while remaining firmly grounded in their core ideology.

- Example: In the past, wholesalers would purchase large quantities of goods from Procter & Gamble (P&G) every few months, which meant P&G had to constantly hire and fire workers to meet the intermittent demand. The company put an end to the practice by committing to a BHAG: They would bypass wholesalers and go straight to retailers, enabling the company to employ workers year-round. P&G had to open hundreds of warehouses and build a massive salesforce but P&G president Richard Deupree saw the steady employment of thousands of workers as worth the risk. It was aligned with the company’s core ideologies of respect and concern for the individual, continuous self-improvement, and honesty and fairness. They achieved their BHAG within four years.

3. Make it institutional. A BHAG should be built into the organization and should be exciting enough to maintain momentum, transcending any disruptions such as a change in leadership.

- For example, Citicorp started out as a small regional bank called City Bank in the 1890s. Then-president James Stillman set the BHAG “to become a great national bank,” and leader after leader picked up from where their predecessor left off, until Citicorp accomplished their BHAG.

4. Keep setting more BHAGs. Visionary companies aren’t complacent; they know that the work isn’t done just because they’ve reached a goal. Instead, they have other BHAGs lined up and employ other ways to stimulate progress (as we’ll discuss in following chapters). Without another BHAG to pursue, they end up becoming stagnant.

- For example, Ford had only a 15 percent market share but worked hard to take the number one spot from GM. Having reached their BHAG, Ford became complacent, which gave GM a chance to reclaim the top spot.

Exercise: Define Your BHAG

A BHAG inspires people, creates momentum, and stimulates progress. If you don’t have a BHAG, now is the time to set one.

Paint a clear picture of where you want to be 10 years from now. Think in terms of operations (number of stores, revenues, etc.), products or services, and even awards you want to win. List them below.

How can you condense these aspirations into a clear, concise goal? (For example, “Make a sale every two minutes.”)

What do you want this goal to motivate people to do? How do you think your goal statement is exciting enough to accomplish this?

How does your BHAG align with your core philosophy?

Chapters 6-7: Cultivate the Right Culture

In this chapter, we’ll debunk two myths: first, that anyone can fit right in at a visionary company, and second, that visionary companies carefully plan out every move.

The Cult-Like Characteristics of Visionary Companies

People see visionary companies as dream workplaces and consider their biggest hurdle to be getting in the door. And while you likely have to go through stringent screening processes to land a spot in a visionary company, you might encounter an even bigger hurdle as you try to fit in. Contrary to the myth, a visionary company isn’t the best place to work for everyone; some people just don’t fit in. It’s either you’re in or you’re out—there’s no in between. This is because visionary companies want to preserve their core philosophy and thus make sure that everyone in the company is compatible with their ideals.

- For example, at Disney, everyone has to embrace wholesomeness, adhering to a strict grooming code and sanitized language—Walt Disney was said to fire anyone who uttered a swear word in the presence of others. Such rules may seem extreme, but they helped preserve the company’s core philosophies after Walt’s death.

The workplace culture of a visionary company can best be described as “cult-like.” The word “cult” may have negative connotations, especially when it refers to a cult of personality, or the radical devotion to an individual. But in visionary companies, workers don’t channel their devotion towards a rock-star leader; instead they channel it towards the company and what it stands for.

While Collins and Porras stress that visionary companies aren’t cults, they did find that the companies consistently demonstrated three cult-like practices and characteristics to make sure that everyone is on the same page.

1) Alignment

Visionary companies have a tough screening process to ensure that new hires fit seamlessly into the organization. They reward behaviors that are compatible with the company’s core are rewarded, while those that aren’t compatible with the core are penalized.

- For example, Nordstrom rewards those who are aligned with the core philosophy of outstanding customer service. Exceptional “Nordies” are entitled to big store discounts, while those who are unpleasant towards customers get sent home for the day.

Visionary companies also implement profit-sharing schemes that increase employees’ psychological commitment to the company.

- For example, P&G gave employees stock options to increase their psychological buy-in. Employees then see their hard work and success as intertwined with the company’s success.

2) Indoctrination

Visionary companies immerse new employees in their core ideology. They require newbies to attend orientation seminars that highlight the company’s history, values, and traditions. They hire young employees, molding them into future leaders of the organization. They expose employees to stellar examples of those who embody the company ideology. Some companies even have their own songs or cheers to bolster employees’ corporate fervor.

- For example, at IBM, newbies learn about the corporate philosophy at the Management Development Center and sing hymns out of the Songs of the IBM songbook. At Disney, every new employee takes part in an orientation seminar called “Disney Traditions'' at Disney University.

3) Exclusivity

Visionary companies want their employees to feel like they are part of a special, elite group. They encourage their workers to socialize among themselves and not with outsiders. They use insider-only language and fiercely guard company secrets and information.

- For example, Disney uses a unique language, referring to employees as “cast members,” customers as “guests,” a work shift as a “performance,” and so on. These terms further the distinction between insiders and outsiders and make employees feel like they’re part of something special.

Anyone who doesn’t align with the corporate philosophy or company culture will either choose or be asked to leave. This doesn’t mean that there is a lack of diversity in visionary companies. Color, gender, size, shape—these things don’t matter, as long as you’re compatible with the core.

How Cultish Culture Supports Progress

All these efforts to ensure that employees are a good fit might seem too restrictive and controlling. In a sense they are—visionary companies have these measures in place to uphold their fervently held philosophies.

However, with cult-ish practices in place, they are not only able to preserve the core, but are also able to entrust their employees with operational autonomy. Rather than turning employees into unthinking robots, visionary companies empower them to think for themselves, innovate, and make bold moves—all while strongly adhering to the core philosophy. When they see that employees embody what the company is all about, visionary companies give them the wings to fly.

- For example, Nordstrom’s employee handbook tells employees the core philosophy (“to provide outstanding customer service”) and gives them plenty of leeway to act as they see fit by giving only one rule: “Use your judgment in all situations.”

Darwinism in Visionary Companies

With operational autonomy, employees feel free to explore, experiment, and innovate—within bounds—which sprouts new, sometimes surprising, branches of business for visionary companies. This, along with visionary companies’ willingness to make the most of unexpected opportunities, debunks the myth that visionary companies’ success is wholly a result of deliberate planning.

Visionary companies don’t follow a plan that’s set in stone. They transform over time in much the same way that species change. The authors liken the process to Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory, where species evolve over time through a process of “variation,” changing to adapt to their environment, and then “selection,” wherein only the strongest variants survive.

While visionary companies do a fair amount of strategic planning, such as setting BHAGs, they also make use of their own process of variation and selection, keeping the best results of their experiments and making the most of opportunities that come their way.

- For example, in 1937, Marriott found that their restaurant near Hoover Airport had many customers en route to the airport, buying meals and snacks to eat on their flights. J. Willard Marriott immediately set up a meeting with Eastern Air and arranged to deliver packed lunches for their flights. Within a few months, Marriott was catering 22 flights per day on American Airlines, eventually catering to over a hundred airports. Marriott’s experiment as a result of one odd variation opened up an unexpected branch of business for the company.

How to Stimulate Evolutionary Progress

The research suggests that comparison companies tend to tamp down revolutionary progress, while visionary companies actively create an environment of evolutionary progress through the following six methods:

1) Make Room for Unplanned Variation

The research found that 12 out of 18 visionary companies gave their employees more freedom and autonomy—allowing them to experiment with new products, for example—versus the comparison cases. When people have the room to let their creativity run wild, they can come up with the most unexpected variations.

- For example, the first 3M laboratory was small and practically bare, but it provided enough space for employees to experiment. Here, they invented Three-M-Ite, the company’s first profitable product.

2) Act Quickly

They don’t get stuck doing long drawn-out feasibility studies or having endless meetings to decide on the next step. As long as an idea is consistent with the core ideology, visionary companies move full speed ahead. Visionary companies are fast on their feet—when they see an opportunity, they seize it. When they hear of a customer problem, they quickly try to find a solution.

- For example, a 3M employee heard a customer complaining about how adhesive tapes didn’t do a good job of separating the colors to achieve two-tone auto paint jobs. The employee proceeded to invent 3M masking tape. This marked the beginning of 3M’s evolution from being just a sandpaper company.

3) Take Baby Steps

One experiment after another, one step after another, can lead to a game-changer. It can be challenging and risky to make a major shift in the business, so take small steps in the direction you want to go. If management is iffy about backing a big project, they might be more open if you ask for permission to do an experiment to prove its feasibility.

- For example, American Express started out as a freight company that introduced a money order service to meet a growing demand. Then, after company president J. C. Fargo encountered problems encashing letters of credit on his travels, American Express created traveler’s checks. And then, at their Paris office in 1895, an employee surreptitiously opened windows to sell tickets to steamships, addressing a need of American travelers—expanding American Express’s business into travel.

4) Accept That Mistakes Are Part of the Process

Stimulating evolutionary progress is a continuous process of trial and error. Evolution isn’t a perfect process; failed experiments (and there can be many) that don’t result in new business are an inherent part of it, just as some mutations don’t survive as a species evolves.

- For example, Johnson & Johnson had successful experiments like Band-Aids, but also had many experiments that didn’t work: Kola stimulants, ibuprofen pain relievers, and colored casts that stained hospital linens are just some of their failed ventures.

5) Build a Clock

Visionary companies don’t just say that their employees can experiment; they reinforce the idea by establishing mechanisms to encourage experimentation, product development, internal entrepreneurship, and idea dissemination. These mechanisms come in the form of targets, awards, grants, and open communication channels.

- For example, 3M has the “30 percent rule,” expecting divisions to generate 30 percent of annual sales from new products released within the last four years. The company also gives out the Genesis Grants, which are funds earmarked for developing prototypes and market tests. And they have forums where people can share the latest products and exchange ideas.

6) Maintain the Core

Species have a fixed genetic code. They mutate to adapt to their environments, not to become another species altogether. The same is true for visionary companies: Their core philosophy serves as the genetic code, guiding them, holding them together, and imbuing them with a purpose and spirit as they morph and evolve. While experimentation allows for variation, a core philosophy leads to selection—visionary companies choose only the things that work and that fit in with their core ideology.

- For example, in keeping with their core philosophy of innovation and problem-solving, 3M only selects ideas that are new, useful, and reliable—solutions to real problems that people have, not just novelty items that meet no real need.

Exercise: Create an Environment for Progress

Visionary companies have systems and methods to stimulate evolutionary progress. Find opportunities to foster experimentation and innovation within your company.

Visionary companies took incremental steps to pivot their business, sometimes starting with little experiments. Describe a project that your management seems to be wary of. (For example, the management of a chain of coffee stands might be hesitant to introduce snacks as part of their product line.)

What small experiments can you do to prove its feasibility? (For example, you can convince them to sell snacks at just one coffee stand for a month.)

What are two or three reasons that employees within your company might be hesitant to innovate or share new ideas?

What practices or policies can you put in place to encourage employees to experiment and explore new ideas?

Chapter 8: Promote From Within

Visionary companies debunk the myth that hiring from outside can revitalize a company. Instead, they promote homegrown, philosophy-supporting leadership in order to preserve their core philosophy.

While both visionary companies and their comparisons have had great leaders at various points in their long histories, comparison companies more often brought in outsiders to fill chief executive roles in the hopes of stimulating progress. The research revealed that visionary companies hired only 3.5 percent of their 113 chief executives from outside versus the comparison companies’ 22.1 percent out of 140.

The Leadership Continuity Loop

To ensure continuity, visionary companies have a leadership loop, which has three essential elements.

1. They develop leaders and come up with a succession plan. Visionary companies have formal management development programs to help them identify and train top managerial talent in the organization. Leaders also put a lot of thought into the best person to succeed them, sometimes planning years in advance.

- Example: Motorola founder Paul Galvin began preparing his son Bob for a transfer of power while Bob was still in high school. For 16 years, Bob worked his way up from store clerk to president. When his father died, Bob almost immediately started with his own succession plan, even though he didn’t leave until 25 years later.

2. They have a list of strong internal candidates. Visionary companies have a culture of developing and training leaders through intensive management training programs. As a result, the companies often have a number of capable candidates who are ready to take on a leadership role when needed.

- For example, General Electric CEO Reginald Jones started looking for a replacement seven years prior to his departure. He cut the list of internal candidates down from 96, to 12, to six. He then put the remaining candidates through challenges, interviews, and evaluations before choosing Jack Welch. Welch may be GE’s most famous CEO, but he was just one among a list of excellent candidates, many of whom went on to become CEOs at other companies.

3. They ensure continuous excellent leadership from within. Those who find themselves in leadership roles at visionary companies then keep the leadership loop going by planning for their successor.

- For example, before Richard Deupree became CEO at P&G, he trained under two people who had also served as CEO before him. Deupree then groomed the next four people to hold the CEO position after him.

These three elements form a never-ending loop that allows the company to have leadership that’s consistently aligned with the core philosophy—even as the company goes through transitions.

What Happens Without a Leadership Loop

When any of these elements is missing, a company ends up with a leadership gap.

Without good people leading the way, a company may find itself stuck, unsure of how to move forward. They may then scramble for a replacement from outside, hoping this savior will give the company some much-needed stimulation. However, bringing in an outsider who is not aligned with the company’s core philosophy typically doesn’t produce good results. The outsider, lacking a true understanding of the company’s core values and purpose, may steer the company in a damaging direction.

- For example, Colgate neglected to come up with a succession plan, so the company merged with Palmolive-Peet and let Palmolive’s Charles Pearce take over. Pearce was obsessed with expansion and ignored Colgate’s core philosophy of dealing fairly with retailers, driving a hard bargain and making enemies of the retailers. During Pearce’s tenure, Colgate’s average profits dropped by more than half.

How to Start a Cycle of Excellent Leadership

Instead of relying on outsiders, it’s important to think about creating your leadership continuity loop—no matter your level or the size of your company.

If you’re a CEO or a member of top management, you should identify, train, and promote top managerial talent who are grounded in the core philosophy and who aren’t afraid of making bold changes to move the company forward. Formulate a long-range succession plan so that passing the torch from one generation to the next will be smooth and seamless. If you have an immediate need for a new leader and have no choice but to look outside your organization, make sure that your chosen leader is compatible with the company’s core philosophy.

- For example, if your company is dedicated to creating high-quality electronics, you shouldn’t bring in a leader who’s willing to churn out subpar products for higher margins.

If you’re a manager, you can think about developing leaders and coming up with a succession plan for your department or group. Think of candidates who can replace you if you suddenly had to leave, and consider the type of training they’ll need to be able to fill your shoes. If you’re an entrepreneur, think long-term—start thinking about how your business can endure from generation to generation, long after you’re gone.

(Shortform note: Read our guide to The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership for tips on putting together a succession plan.)

Exercise: Create a Leadership Continuity Loop

One of the keys to building a visionary company is to have a leadership continuity loop. Make sure your company (or department) has capable people ready to take your place.

Imagine that you and your next-rank member of management suddenly left the company. Who would you trust to take your place? List two or three candidates and why you think they’d be a good choice.

Evaluate each candidate on your list. What kind of skills do they need to develop in order to be ready for the role?

What kind of training exercises can you set for your candidates to hone the skills necessary for the position?

Chapter 9: Never Settle for Good Enough

This chapter debunks the myth that visionary companies are obsessed with beating their competitors.

Visionary companies recognize that simply aiming to beat their competitors puts a cap on their goals—once they beat the competition, they can drift into contentment. But visionary companies recognize that contentment is one step away from complacency, which may then lead to decline. So, visionary companies are always on a quest for continuous improvement.

The research found that in 16 out of 18 cases, visionary companies were more intent on self-improvement than their comparisons. In particular, they did two things: They seeded discomfort by employing various mechanisms of discontent and they made more long-term investments.

Seed Discomfort

Visionary companies want their people to feel discontented with their accomplishments because it pushes them to strive for more. To create motivational discontent, visionary companies use various tactics.

Tactic 1: Internal Competition

Instead of looking outside for motivation, visionary companies look inside and have employees engage in healthy competitions. Whether it’s brands trying to outdo each other in sales or R&D groups in a race to come up with the best new product, internal competition can fuel excitement, creativity, and innovation, and can ultimately be good for the bottom line.

- For example, in 1931, P&G had the best products in the market with no real competition in sight, so they decided to pit their brands against each other. This proved so effective at lighting a fire under their people that other companies—including their comparison company Colgate—started mimicking the practice many years later.

Tactic 2: Employee Rankings

Some companies employ the internal competition tactic on a smaller scale, ranking individual performance. This serves to push employees to perform at their best—no one wants to find themselves at the bottom of the pack.

- For example, HP managers had to come up with a pooled ranking for all their people, so they would gather and have impassioned arguments until they came up with a ranked list.

Tactic 3: Forced Innovation

Some companies believe that necessity is the mother of invention, and so they create necessity by phasing out profitable products. This then pushes employees to come up with replacements to make up for the loss in sales.

- For example, Motorola forced itself to “innovate or die” by discontinuing older products that made up a big bulk of their sales.

Tactic 4: Think Like the Competition

Visionary companies put themselves in the shoes of their competitors to probe for strengths and weaknesses from a different perspective. The companies then use their insights to come up with plans to leverage strengths and safeguard themselves against weaknesses.

- For example, Boeing managers were tasked with seeing the company through the “eyes of the enemy.” They had to evaluate Boeing’s weaknesses and strengths and come up with a way to beat Boeing. They then had to determine how Boeing could respond to this threat.

Tactic 5: Year-On-Year Ledgers

Visionary companies track their year-on-year performance. This ensures that they stay on the path of continuous improvement and enables them to immediately catch and remedy any downward trend.

- For example, Wal-Mart had “Beat Yesterday” ledger books that tracked sales figures and compared them to the previous years’ figures right down to the day. Year on year, they compared the first Monday, first Tuesday, and so on.

Think Long-Term

Aside from creating discontent with the status quo, visionary companies also make it a priority to build for the long-term—and for visionary companies, “long term” means several decades. The research revealed that, compared to the comparison companies, visionary companies made more long-term investments in several areas: new property, plants, and equipment; research and development; early adoption of new management methods, industry practices, and technology; and human capital.

- For example, P&G, Disney, and IBM made big investments in their workforce, establishing “universities,” training centers, and development programs. This investment in human capital ensures that visionary companies continue to attract and retain great talent.

With an eye on the future, visionary companies refuse to sacrifice long-term goals for short-term profit. To them, making a quick buck is pointless if it won’t be good for the company in the long run.

- For example, Texas Instruments (TI) started producing cheap consumer products and dropped their prices to increase their market share, but this only eroded the company’s reputation as a maker of excellent products. In contrast, HP never stopped investing in human capital, hiring the brightest scientists and engineers, even when the company was struggling to stay afloat. This proved to be a worthy investment as the brilliant team came up with profitable products over the next two decades.

The quest for self-improvement is never-ending, because success is never final. Even when a company is at the top, there is no guarantee that they’ll stay there.