1-Page Summary

Chasing Lincoln’s Killer is an account drawn from archival materials of John Wilkes Booth’s assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865 and the 12-day pursuit of Booth and his co-conspirators through Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia.

In the spring of 1865, Abraham Lincoln was beginning his second term as president, and Washington, D.C. was starting to breathe more easily as the four-year Civil War wound down.

However, many rebels and Confederate sympathizers refused to give up the so-called lost cause of slavery and states’ rights, holding out hope of eventually winning. Washington and the surrounding countryside harbored numerous spies and supporters of the Confederacy looking for ways to undermine the Union.

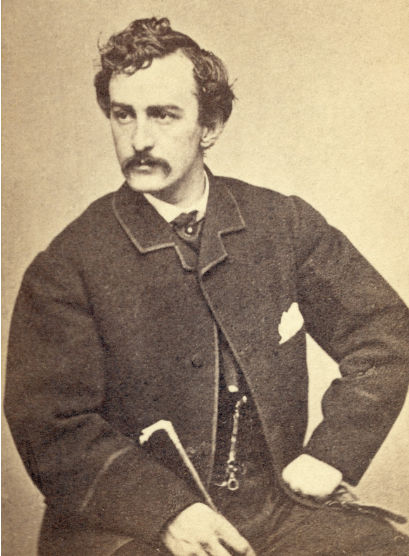

One vehement anti-Unionist was a popular 26-year-old actor, John Wilkes Booth. He was a racist and Lincoln-hater acquainted with Confederate agents and sympathizers from Canada and New York City to Virginia. In the spring of 1865, after General Robert E. Lee’s disappointing surrender, Booth became increasingly dismayed with Lincoln—and a belief took root that killing Lincoln would rally Confederate sympathizers and veterans to renew the fight and defeat the Union.

Planning the Assassination

Booth’s opportunity to kill Lincoln came on April 14 when he learned that the President and Mary Todd Lincoln would be attending the performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre that evening. Having acted in other performances, Booth was familiar with the theater’s layout and knew he could shoot Lincoln in his balcony box and get away quickly.

However, Booth knew he’d need help because, in addition to killing Lincoln, he wanted to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. So at around 8 p.m. (curtain time for the play), Booth met with a group of co-conspirators at a hotel near the theater and assigned them roles.

Booth’s co-conspirators and their roles were:

1) David Herold, a tracker and outdoorsman, would guide conspirator Lewis Powell to Secretary of State Seward’s home in D.C. and wait while Powell killed Seward (Powell didn’t know his way around the city). Then Herold was to accompany Powell out of the city to meet up with Booth south of Washington, in Maryland, after Booth killed Lincoln.

2) Lewis Powell, a former Confederate soldier, would assassinate Seward, who was recuperating in bed at his home from a serious carriage accident.

3) George Atzerodt would kill Vice President Andrew Johnson in his room at the Kirkwood House hotel in Washington. Atzerodt had doubts about the assignment and didn’t sign on until Booth threatened him.

After the meeting, Booth checked on the progress of the play at about 9 p.m., then went to a nearby stable and got his horse, which he asked an unwitting theater employee to hold for him at the theater’s back door.

The Assassination Plot Unfolds

Booth returned to the theater at 10 p.m. and climbed the stairs to the balcony. In the vestibule leading to the president’s box, he pulled out a single-shot pistol and knife. He waited until there was just one actor on stage, who he knew would deliver a big applause line generating a reaction that would muffle his shot. He opened the door to the president’s box at 10:31 p.m., entered, and fired as he heard the applause line, striking Lincoln in the head. A guest in the box lunged at Booth, but Booth stabbed him and escaped by climbing over the balcony, dropping to the stage (breaking his leg), and racing through the wings and out the back door to his horse.

Meanwhile, when Powell tried to kill Secretary of State Seward at his home, he encountered fierce opposition from Seward’s family and staff. After stabbing Seward and others, he fled the house, only to find that Herold had abandoned him when the fighting broke out. Lost in the city, Powell slept in a tree for two nights, then eventually found his way to Confederate sympathizer Mary Surratt’s boarding house, which he’d visited with Booth before.

For his part, Atzerodt abandoned his assignment to kill Vice President Johnson, spent the night in his hotel room, then fled to a cousin’s house in Maryland.

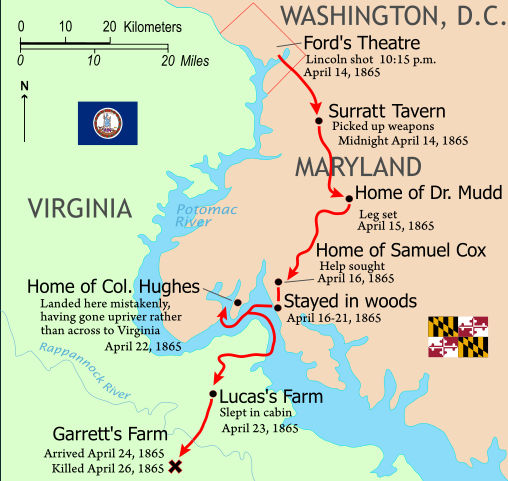

Booth and Herold both got out of the city unimpeded and met up in Maryland. Their plan was to continue fleeing south to Virginia, a Confederate state, where they hoped to find support and acclaim. Early on, they stopped at the Maryland farm of Confederate sympathizer Dr. Samuel Mudd, who splinted Booth’s leg.

12 Days on the Run

As Lincoln died and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton launched an investigation and manhunt for the killers, Booth and Herold’s flight from Washington continued as follows:

- April 15-19: Booth and Herold rested at Mudd’s farm, then left that evening to connect with an ex-Confederate officer who would help them get across the Potomac River to Virginia. To avoid troops searching for Booth, they hid in the woods until nightfall on April 20, rather than staying at the officer’s farm.

- April 20-21: That night, a Confederate sympathizer led them to the river and a fishing boat. He showed them how to steer a course in the darkness to the other side. Booth and Herold got turned around in the darkness and rowed in the wrong direction. Early on April 21, they landed back in Maryland, farther north than they had been before. They stayed that night with a friend of Herold’s.

- April 22-23: Late on the night of April 22, Booth and Herold got back on the Potomac and crossed to Virginia, and in the early morning hours, they met another Confederate agent who took them to a doctor recommended by Mudd to check Booth’s leg. However, the doctor suspected their identities and refused to help them. They stayed at a nearby cabin after threatening the African-American man who lived there. The next morning, they paid him for use of a wagon and team and drove to Port Conway on the Rappahannock River, planning to get a ride across the river to Port Royal and catch a train heading south.

- April 24-26: At the Rappahannock, Booth and Herold encountered three Confederate soldiers, who agreed to help them get across the river and assist them on the other side. After landing, the men came upon a farm owned by Richard Garrett and asked to stay the night, claiming that Booth was a wounded Confederate soldier. Garrett allowed Booth to stay at the farm, while Herold and their three Confederate companions rode into the town of Bowling Green for lodging. The Garretts soon became suspicious of Booth and Herold and refused their request to stay another night. When the fugitives promised to sleep in the barn and leave the next day, the Garretts agreed—but they bolted the barn doors from the outside after Booth and Herold went to sleep.

Meanwhile, Powell and Atzerodt were both caught and arrested. Powell was arrested when he showed up at the Washington boarding house of Confederate sympathizer Mary Surratt (and Surratt was arrested as well due to her known ties to Booth and other conspirators). Atzerodt was arrested at his cousin’s house in Maryland after he aroused suspicions by joking that he’d killed Lincoln and confirming the attack on Seward, and another guest reported him to authorities.

Dr. Mudd was arrested after changing his story several times about the two men he had assisted (Booth and Herold) the night of the assassination. He claimed he didn’t know them, then said he eventually recognized Booth as someone he’d met previously.

The Fugitives’ Last Stand

After a tip from a witness who’d seen two men, one of whom had a broken leg, crossing the Rappahannock, the 16th New York Cavalry raced to Port Royal in pursuit. On April 26, the cavalry tracked down one of the fugitives’ Confederate helpers, who confessed to knowing Booth’s location. The cavalry then rushed to the Garrett farm.

Booth and Herold heard them coming up the lane, but when they couldn’t get the barn doors open, they realized they were locked in. The troops surrounded the barn, but instead of storming it, they tried to persuade Booth and Herold to surrender. Herold gave himself up, but Booth refused. The troops set the barn on fire.

A sergeant watching Booth through a gap in the wall boards saw him draw his pistol and also raise the Carbine held in his other hand as if to fire through the open door at the troops outside. So the sergeant aimed and fired his own pistol through the crack, striking Booth in the neck. The soldiers brought Booth outside, still hoping to take him back to Washington to face justice—but he’d been mortally wounded and died hours later as the sun rose.

Trial and Execution

On July 5, eight co-conspirators were tried and found guilty. The next day, four—Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt—were hanged. Mary Surratt was mistakenly believed to have played a central role in organizing the plot. Dr. Mudd was sentenced to prison—however, his sentence was commuted four years later by President Johnson, in part for his help during a prison epidemic. Mudd returned to his farm, where he died in 1883.

Introduction

In Chasing Lincoln’s Killer, author and Lincoln historian James L. Swanson draws on archival material and trial transcripts to create a vivid account of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and the 12-day pursuit of killer John Wilkes Booth and his co-conspirators through Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. This book is condensed from a longer work to adapt it for young readers.

(Shortform note: We compressed the book’s 14 chapters into 8 to clarify the timeline and make the story more cohesive.)

Washington, D.C. in 1865

In the spring of 1865, Abraham Lincoln was beginning his second term as president, and Washington, D.C. was starting to breathe more easily as the four-year Civil War wound down.

However, many rebels and Confederate sympathizers refused to give up the so-called lost cause of slavery and states’ rights, holding out hope of eventually winning. Washington and the surrounding countryside harbored numerous spies and supporters of the Confederacy who looked for ways to undermine the Union.

One vehement anti-Unionist was a popular 26-year-old actor, John Wilkes Booth. He was a racist and Lincoln-hater who maintained contact with a broad range of Confederate agents and sympathizers during and after the war, from Canada and New York City to Virginia. In 1864, he had concocted a failed plot to kidnap the president and hold him hostage in the Confederate capital of Richmond. While the plotters were lying in wait for Lincoln’s carriage, Lincoln was speaking at the very hotel where Booth was living.

In the spring of 1865, after General Robert E. Lee’s disappointing surrender, Booth became increasingly dismayed with Lincoln—and a belief took root that killing Lincoln would rally Confederate sympathizers and veterans to renew the fight and defeat the Union.

Precipitating Events

The key events in Washington that shaped Booth’s obsession with killing Lincoln included:

- March 4, 1865: With the Civil War nearly won, Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address, a brief 701-word speech in which he talked of binding up war wounds and restoring peace and unity as a nation. (“With malice toward none, with charity for all … let us strive on to finish the work we are in.”) A photographer recording the scene captured a photo of Booth among the spectators in a balcony above the stands.

- April 3, 1865: The Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia fell, and people began celebrating in the streets of Washington, waving paper flags with the message, “We celebrate the fall of Richmond.” A few days later, Booth commented while drinking at a bar in New York City that he’d been close enough to Lincoln on Inauguration Day to have killed him. (“What an excellent chance I had…”)

- April 9, 1865: Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. Back in Washington from New York, Booth roamed the streets in despair.

- April 11, 1865: A celebratory parade assembled at the Executive Mansion (an early name for the White House) and Lincoln gave a long speech in which he advocated giving African-Americans, especially those who had fought for the Union, the right to vote. In the audience, Booth turned in anger to a co-conspirator, David Herold, and vowed to kill Lincoln: “Now, by God, I’ll put him through.” As they were leaving, he told another co-conspirator, Lewis Powell, “That is the last speech he will ever give.”

- April 13, 1865: Crowds celebrated the end of the war by lighting up Washington with torches, gaslights, and fireworks. Booth watched for a while, then went to his room at the National Hotel after midnight but couldn’t sleep.

- April 14, 1865: While picking up his mail the next morning at Ford’s Theatre, which accepted mail for actors, Booth discovered that preparations were being made for President and Mrs. Lincoln’s planned attendance at a performance of Our American Cousin that evening.

Chapters 1-2: Planning the Assassination

Booth spent April 14 laying plans for the assassination, which required connecting with multiple co-conspirators. He knew he’d need help escaping to Virginia, a Confederate state where he hoped to find support and acclaim.

He’d also need help because, in addition to killing Lincoln, he wanted to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. He hoped that killing several key government officials would rally Confederate sympathizers and veterans to renew their fight.

Introducing the Co-Conspirators

Following are brief bios of the key co-conspirators and their roles.

1) David Herold: Booth’s most-loyal follower, Herold was a tracker and outdoorsman whose role in the assassination plot was to guide conspirator Lewis Powell to Secretary of State Seward’s home in D.C., and wait while Powell killed Seward (Powell didn’t know his way around the city). Then Herold was to accompany Powell out of the city to meet up with Booth south of Washington, in Maryland, after Lincoln’s assassination.

2) Lewis Powell: Powell was a former Confederate soldier and loyal Booth follower, whose job of assassinating Seward was expected to be fairly easy: Seward was barely conscious and recuperating in bed after a serious carriage accident.

3) George Atzerodt: Assigned to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson in his room at the Kirkwood House hotel in Washington, Atzerodt had doubts about the plan from the beginning. As a motivator, Booth threatened to implicate Atzerodt in the plot afterward regardless of his actual involvement, so he’d be hanged anyway.

4) Mary Surratt: A 42-year-old widow, Surratt owned a tavern in Maryland and a boarding house in Washington, D.C. Her son, John Harrison Surratt, was a friend of Booth’s and a Confederate secret agent; Booth and associates regularly visited her boarding house.

5) John Harrison Surratt: A Confederate agent and son of boarding house owner Mary Surratt, John Surratt was in Elmira, N.Y., during the assassination plot, but investigators searched for him several times at the boarding house because he was known to be friends with Booth. (After learning of the assassination, Surratt fled to Canada, then Europe; he joined the pope’s army in Rome, Italy, and evaded capture for a year. When he was brought back and tried, the jury couldn’t reach a verdict.)

6) Dr. Samuel A. Mudd: A 32-year-old doctor who lived on a farm in Bryantown, Maryland, Mudd was a racist and Confederate sympathizer who had owned slaves until the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Booth met Mudd while looking for recruits for his kidnapping plot, and Mudd introduced Booth to John Surratt in Washington. Mudd held supplies at his farm to aid the conspirators in the kidnapping plot that never happened. After the assassination, Mudd aided Booth and Herold.

Booth’s Preparations for Killing Lincoln

Booth made the following preparations for the attack at Ford’s Theatre:

- He went to Kirkwood House, a hotel where Vice President Andrew Johnson was staying, and left an inexplicable note for Johnson at the front desk reading: “Don’t wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth.”

- He visited Mary Surratt’s boarding house looking for John Surratt, who wasn’t there. He asked Mary Surratt to deliver a package (binoculars) to her tavern keeper in Maryland and let him know that Booth would stop there late that night.

- Back in his room at the National Hotel, Booth selected his weapons for attacking Lincoln—first, a .44 caliber single-shot, muzzle-loading Deringer pistol. This was a pocket-sized handgun that shot a large one-ounce ball. The pistol took more than 20 seconds to reload, which Booth wouldn’t have time to do if he missed. So as a backup, Booth chose a long, sharp Rio Grande camp knife. He gathered a few other items, including a compass, whistle, datebook and pencil, money, small knife, and photos of five girlfriends.

- Booth gave a fellow actor a sealed envelope to deliver to a newspaper the next day, explaining the reasons for the attacks and naming everyone involved. (However, it was never delivered because the friend, afraid of being linked to Booth after the assassination, burned it.)

- At around 8 p.m. (curtain time for the play) at the Herndon House Hotel near Ford’s Theatre, Booth met with the co-conspirators he’d recruited months ago for the kidnapping scheme. According to Atzerodt’s account of the meeting, Booth said he would kill the president that evening at 10 p.m., which would “be the greatest thing in the world.” Having acted in other performances, Booth was familiar with the theater’s layout and knew he could shoot Lincoln in his balcony box and get away quickly. He gave Atzerodt and Powell instructions for killing Vice President Johnson and Secretary of State Seward.

- Booth checked on the progress of the play at about 9 p.m., then went to the nearby stable and got his horse, which he asked a theater employee, Edman Spangler, to hold for him at the theater’s back door.

Chapter 3: The Assassination Plot Unfolds

Lincoln, his wife Mary Todd Lincoln, and their guests Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancé Clara Harris arrived at the theater after the play had begun. However, the director stopped the play, the band played “Hail to the Chief,” the audience cheered, and Lincoln bowed to the crowd.

After having a drink at a saloon, Booth entered the theater lobby at 10 p.m. and climbed the stairs to the balcony, where he opened the vestibule door unimpeded. He closed and blocked it behind him, and waited outside another door to Lincoln’s box. He could see through a peephole that he may have made that Lincoln was seated in a rocking chair closest to the door holding Mary’s hand. Their guests were seated on Mary’s other side.

Four scenes remained in the play. Booth pulled out his pistol and knife. He waited until there was just one actor on stage, Harry Hawk, who he knew would speak a big applause line generating a reaction that would muffle his shot. He opened the door and entered the president’s box at 10:31 p.m.

No one in the box noticed as Booth stepped toward Lincoln and raised the pistol to shoulder height. When Hawk spoke the line, “You sockdologizing old mantrap,” the audience burst into laughter, and Booth fired. The bullet struck Lincoln on the left side of his head below his ear, then traveled through his brain and stopped behind his right eye. Lincoln’s head fell forward, and he slumped in the chair.

Some theatergoers heard the shot and thought it was part of the play. However, the Lincolns’ guest, Major Rathbone, recognized it as gunfire. As he got up and moved toward Lincoln, Booth stabbed at him with his knife, shouting “Freedom!” Booth then climbed over the box railing and jumped to the stage, landing awkwardly and injuring his left leg. He yelled the state motto of Virginia, in Latin, “Thus always to tyrants,” and then “The South is avenged!” He ran into the wings, slashing at anyone in front of him, while an audience member heard Booth say, “I have done it.” Booth reached the back door to the alley, mounted his horse, and galloped away.

The Attack on Seward

As the attack unfolded at the theater, about a mile from the White House, Secretary of State Seward lay in bed with his daughter Fanny by his side. With David Herold waiting outside, Lewis Powell knocked on the door and told the servant who answered that he had medicine from Seward’s doctor, which he needed to give directly to the patient. He pushed past the doubtful servant and started upstairs, running into Seward’s son Frederick on the way.

They scuffled, and Powell tried to shoot him but his pistol malfunctioned. Powell beat Frederick with the gun as the servant ran for help. Fanny looked out of her father’s bedroom door, inadvertently revealing his location, and Powell barged into the room. An army nurse also in the bedroom fought Powell and Powell stabbed him. Powell managed to stab Seward in the side of the face while Fanny tried to protect him.

Outside, Herold could hear the commotion and took off on his horse, leaving Powell to fend for himself. Another Seward son, Augustus, awoke and joined the fray, and the defenders wrestled Powell out of the bedroom and into the hall. Powell finally fled, finding his horse outside but not Herold. He threw his knife on the ground and rode away. While Seward was seriously injured, he managed to whisper that he was alive, and the householders sent for doctors and police.

A Mortally Wounded President

At Ford’s Theatre, a 23-year-old Army surgeon in the audience, Dr. Charles Leale, rushed to the president’s box after Booth’s escape. He examined Lincoln, who wasn't breathing, and found the large bullet hole in his head. He removed the blood clot at the bullet hole to relieve pressure, then worked to start the president’s heart and breathing. Although Lincoln’s breathing resumed, Leale pronounced his wound mortal.

Lincoln was carried through the crowds and across the street to a boarding house bedroom where more doctors arrived and a death watch began. Other government officials were notified, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton arrived and took charge of mobilizing troops to hunt for Booth and for Seward’s attacker. Stanton also sent guards to Johnson’s and every cabinet member’s house, believing this was a Confederate plot to bring down the government.

The Co-Conspirators Scatter

Although Booth’s plan called for the co-conspirators to meet on a particular hilltop in Maryland after carrying out their assignments, Atzerodt and Powell improvised.

Atzerodt: Although he was supposed to simply knock on the vice president’s unguarded Kirkwood House hotel room door and shoot or stab him when he answered, Atzerodt instead drank awhile in the hotel lobby, then got on his horse and returned to his own hotel room for the night without attempting the assassination.

Powell: After his botched attack on Seward, Powell became lost in the city without Herold as a guide. After sleeping in a tree for two nights, he remembered Mary Surratt’s Washington boarding house, which he’d visited with Booth, and decided to try and find it.

Booth and Herold: Booth and Herold followed the planned escape route out of the city, with Herold some distance behind. Both crossed the Navy Yard Bridge after questioning by a guard, who let each of them pass after some hesitation. They rode 13 miles toward Mary Surratt’s tavern in Maryland, with Herold catching up with Booth near the meeting point. With Booth in increasing pain from his injured leg, they arrived at the tavern, collected the stashed weapons and supplies, and continued riding southeast in search of Dr. Mudd, who lived on a farm near Bryantown, Maryland.

Chapters 4-7: Manhunt

At 7:22 a.m. April 15, at the boarding house across from Ford’s Theatre, Lincoln died and Stanton sent a telegram announcing the news to the nation. The president’s body was placed in a simple pine coffin and soldiers escorted it to the Executive Mansion. At 11 a.m, Vice President Johnson was sworn in as president.

Meanwhile, Stanton escalated the investigation and manhunt for the co-conspirators, calling in troops and police from as far away as New York City. They had numerous pieces of evidence from searching Booth’s room, including letters with the names of associates, but they were also distracted by false sightings and leads.

April 15

Atzerodt: Azerodt left his hotel room and walked to Georgetown, on his way to his cousin’s in Maryland. In Georgetown, he stopped at a store, got a $10 loan by using his pistol as collateral, and continued on.

Booth and Herold: Booth and Herold rested at Mudd’s farm during the day and planned to continue south at nightfall. When Mudd went to town for supplies, he learned that Lincoln had been shot and cavalry troops were searching the countryside for Booth and other associates. A patrol coming from Washington rode past his farm that day but didn’t stop. Afraid and angry that Booth had involved him in the assassination plot, Mudd returned to his farm at 6 p.m. and ordered Booth and Herold to leave.

However, Mudd agreed that if questioned by troops, he’d say only that he’d provided medical aid to two strangers who stopped briefly at his farm, then he’d send the troops in the wrong direction. The doctor also provided Booth and Herold with the names of two local Confederate operatives and directions for connecting with them near the Potomac River, which they would then cross to Virginia. Finally, he passed on the name of a doctor in Virginia. After getting lost, Booth and Herold finally connected late at night with one of the operatives, Captain Samuel Cox, at his farm near the river.

April 16 (Easter Sunday)

Booth and Herold: As Easter dawned, Cox sent the fugitives to a nearby wooded area to hide until nightfall, while he summoned a Confederate secret service veteran, Thomas Jones, who could ferry them across the river. Jones had run a clandestine ferry service between Maryland and Virginia during the war, and he was excited to assist Lincoln’s assassin.

Jones visited Booth and Herold in the woods and persuaded them to stay hidden until troops had moved through the area. He would bring them food and newspapers requested by Booth and would decide the best time to cross the river.

Atzerodt: On Easter morning, Azerodt arrived at his cousin’s home 22 miles south of Washington in Montgomery County, Maryland. The cousins and other guests joked that Azerodt could be the man who killed Lincoln, and Azerodt stupidly joked that he was. Further, he confirmed the news of the attack on Seward. He then traveled farther south to another cousin’s residence. Meanwhile, a suspicious guest at the earlier stop reported him to authorities.

Mudd: Mudd continued to worry about being questioned by troops. In an attempt to make it look like he was a good citizen and absolve himself of responsibility, he sent a cousin to give cavalry officers a vague report that two strangers had stopped at Mudd’s farm and he’d given medical aid. His cousin was slow in delivering the report, and the officers were slow in checking it out.

April 17-18

Powell and Mary Surratt: In Washington, Stanton’s investigators suspected that John Surratt was Seward’s attacker because of his association with Booth, although they had no evidence. As they questioned Mary Surratt at her boarding house, Powell rang the doorbell.

Powell was surprised to find soldiers inside and when they asked his business, he said he was there to dig a ditch for Mary Surratt—however, she refused to confirm the story, saying she didn’t know him. Powell surrendered and soldiers arrested him, Mary Surratt, and everyone else at the boarding house. Searching the house, investigators found photos and documents, including a photo of Booth hidden behind a picture frame, connecting the occupants to the Confederate cause.

Under questioning at headquarters, Mary Surratt admitted only the facts she knew the investigators likely had from other sources. She lied in saying she didn’t know Powell, but acknowledged knowing Atzerodt, whose name had been found in Booth’s room. She provided no clues to Booth’s whereabouts. Investigators arrested and jailed Surratt and Powell, along with several Booth associates who had nothing to do with the assassination. They even arrested the theater employee who’d unwittingly held Booth’s horse, among more than 100 suspects.

Booth and Herold: On April 18, Jones visited Booth and Herold in the woods for the third time, and he brought more newspapers. Booth was stunned to find the newspapers condemning him while portraying Lincoln as a martyr. He was also dismayed at the messiness of Powell’s attack on Seward’s household.

Mudd: On April 18, cavalry officers finally questioned Mudd. He gave vague descriptions of his two visitors and said he didn’t know either of them; further, Mudd tried to send the officers in the opposite direction from the one in which Booth and Herold fled. They searched his property and left, but were suspicious of his story.

April 19-24

On the morning of April 19, tens of thousands gathered in Washington for Lincoln’s funeral procession and waited in line to view his open casket in the Capitol. Afterward, a train carried his body home to Springfield, Illinois.

Atzerodt: Atzerodt had spent four nights at his cousin’s residence, fearing capture if he traveled. On the morning of April 20, soldiers arrived and found him in bed. He surrendered and later confessed many details of the assassination plot and the earlier kidnapping plot, implicating Mary Surratt and Mudd. Stanton offered a $100,000 reward for the capture of Booth, Herold, and John Surratt.

Mudd: Officers questioned Mudd again. He said his injured visitor had worn a false beard. He acknowledged he’d met Booth a few times in the past. After hours of questioning, he said, now that he thought about it, the injured visitor had been Booth.

Booth and Herold: After dark on April 20, Jones led Booth and Herold from their hiding place to the river and a fishing boat. He showed them the course to follow with Booth’s compass and provided the name of a contact on the Virginia side. Booth and Herold shoved off on their own, but soon got turned around in the darkness and rowed in the wrong direction. Early on April 21, they landed back in Maryland, farther north than they had been before. They stayed that night with a friend of Herold’s. Late on the night of April 22, Booth and Herold got back on the Potomac.

In a few hours, they crossed and landed at the mouth of a creek on the Virginia side, stepping on Virginia soil on April 23, nine days after the assassination. They met a female Confederate agent. With the help of others, she obtained horses. They rode to the home of Dr. Richard Stuart, whom Mudd had recommended, but Stuart suspected their identities and refused to help beyond providing some food.

They stayed the night at the cabin of one of Stuart’s neighbors—an African-American man—after threatening him. The next morning they paid him for use of a wagon and team, and drove to Port Conway on the Rappahannock River, planning to get a boat ride across the river to Port Royal and take a train south.

As they negotiated with a fisherman to take them across the river, they were approached by three Confederate soldiers. Herold acknowledged who he and Booth were, and the soldiers agreed to help them get across the river and assist them on the other side.

After landing, the men came upon a farm owned by Richard Garrett and asked to stay the night, claiming that Booth was a wounded Confederate soldier. Garrett was sympathetic because his sons had just returned from the war, and he allowed Booth to stay at the farm, while Herold and their Confederate companions rode into the town of Bowling Green for lodging.

Mudd: On April 24, soldiers again arrived at Mudd’s farm, this time arresting him and taking him to Old Capitol Prison in Washington.

April 25-26

Booth and Herold: Investigators in Washington, who were receiving reports of supposed sightings of Booth and Herold from all over, learned via telegram that two men had recently crossed the Potomac River. So they focused the manhunt on Virginia. A contingent of the 16th New York Cavalry took a steamboat to Virginia, then headed on horseback toward Port Conway.

At the Garrett farm, Booth slept late on the morning of April 25, then entertained the Garrett children with knife tricks in the afternoon. A Garrett son, John, returned from a visit to a neighboring farm and reported the government’s reward for Lincoln’s assassin. Booth decided it was time to move on, but was unnerved when he saw riders passing the farm gate. The Garretts noticed his alarmed reaction and became suspicious.

When Herold returned to the farm from town (without their Confederate companions), Booth asked the Garretts if they could both stay that night. With their father away from the farm that day and the Garretts becoming wary, son John Garrett refused.

Meanwhile, the 16th New York Cavalry arrived in Port Conway in the late afternoon of April 25, and learned that two men, one with a broken leg, had been ferried across the Rappahannock along with three Confederate soldiers, whose names were known. The Union troops crossed and headed for Port Royal, intending to find and question one of the Confederate soldiers.

At the Garrett farm, two of the Confederate soldiers who assisted Booth and Herold galloped up with news that the Union cavalry had crossed the river. As they were talking, a contingent rode past the gate without stopping. Booth and Herold agreed to leave, but not until morning, and they insisted they would need horses.

John Garrett wouldn’t allow them to stay in the house, so Herold decided they’d sleep in the tobacco barn. After Booth and Herold settled into the barn to sleep at 9 p.m., the Garretts, still concerned about what the visitors were up to and worried about losing their horses, bolted the barn doors from the outside and kept watch.

In nearby Bowling Green, Cavalry officers found the third Confederate who’d helped Booth and Herold, and he confessed to knowing their location.

The Fugitives' Last Stand

At 12:30 a.m. April 26, the 16th New York Cavalry raced to the Garrett farm. Booth and Herold heard the horses coming up the lane, but when they couldn’t get the barn doors open, they realized they were locked in. They tried to break through the back of the barn, to no avail.

When the troops held a gun to John Garrett’s head and demanded the fugitives, the Garretts pointed to the barn. Instead of storming the barn, the troops then tried to persuade Booth and Herold to give up. Herold surrendered, but Booth stalled, asking for more time.

The troops decided to burn the barn and ordered the Garretts to pile hay against the sides, which soldiers then lit. A sergeant watched Booth through a gap in the wall boards. When he saw Booth draw his pistol and also raise the Carbine held in his other hand as if to fire through the open barn doors toward the troops outside, the sergeant aimed and fired his pistol through the crack, striking Booth in the neck.

Troops rushed in and carried Booth outside. Paralyzed, he couldn’t swallow and could barely speak, but he whispered, “Tell Mother I die for my country.” Booth begged the soldiers to kill him, but they refused. Hoping to take him back to Washington to face justice, they brought a doctor, who determined the wound was mortal. Booth died hours later as the sun rose.

Chapter 8: Trial and Execution

Despite the hundreds of people originally arrested, including many who had encountered or assisted the co-conspirators, Stanton decided to try only eight: Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, Samuel Arnold, Michael O’Laughlen, Edman Spangler, and Dr. Samuel Mudd.

Arnold and O’Laughlen were involved in Booth’s kidnapping conspiracy, but apparently not in the assassination plot. Nonetheless, they were sentenced to life in prison. Spangler, who had held Booth’s horse behind Ford’s Theatre, was found guilty and sentenced to prison, although he was innocent.

Mary Surratt was believed to have played a central role in organizing the conspiracy, so she was sentenced to death, as were Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt. On July 7, the four were hanged at the same time on an extended scaffold.

Dr. Mudd was sentenced to prison in Florida, but his sentence was commuted by President Johnson four years later in 1869, in part for his help in a prison epidemic. He returned to his Maryland farm, where he died in 1883. Before he died, he confessed to the son of Samuel Cox (whose father had hidden Booth and Herold in the woods until they could cross the Potomac) that he’d recognized Booth the moment he showed up the night of April 14, 1865.

Exercise: Was Justice Served?

Most of the people who saw and knowingly assisted the Lincoln assassination conspirators were not ultimately punished. (Also, an innocent man was punished.)

Do you think those who knowingly assisted the conspirators by providing food, shelter, transportation, and so on, should have been punished? Why or why not?

Do you think Dr. Samuel Mudd was punished appropriately? Why or why not?

Did Mary Surratt deserve a death sentence, although she wasn’t directly involved in planning the assassination? Why or why not?

Would you ever hesitate to report something you knew or felt was wrong? What factors would you consider in deciding whether to report it?