1-Page Summary

Periodically, a new high-tech innovation will transform the way we live or do business and propel its inventors to wealth and fame. More often, though, new high-tech products seem to stagnate and die instead. In Crossing the Chasm, marketing consultant Geoffrey Moore provides an explanation for this, and he presents a strategy for introducing your product effectively into the mainstream market.

His explanation is grounded in the “technology adoption life cycle” (TALC), which predicts how innovations are adopted by different segments of society as a technology matures. Moore argues that there’s a little-recognized gap or “chasm” in this model between the early market and the mainstream market—and failure to cross this gap accounts for the failure of many high-tech products.

In this guide, we’ll discuss Moore’s analysis of the TALC and his strategy for crossing the “chasm,” a strategy that includes targeting a niche market, forming corporate alliances to ensure the customer gets a complete solution, positioning your product as the market leader in that niche, and setting up an effective distribution channel. For each step, we’ll compare Moore’s perspective to other analysts’, including marketing consultant Regis McKenna and sales coach Oren Klaff.

(Shortform note: Moore’s strategy is intended specifically for business-to-business marketing, and thus, he presents most of the principles assuming the target customer is a business, although there are elements that could apply to individual consumers as well.)

The Technology Adoption Life Cycle

To understand Moore’s strategy, you need to understand the chasm between the early and mainstream markets, and to understand the chasm, you need to understand the Technology Adoption Life Cycle (TALC), also referred to as the “diffusion of innovations.”

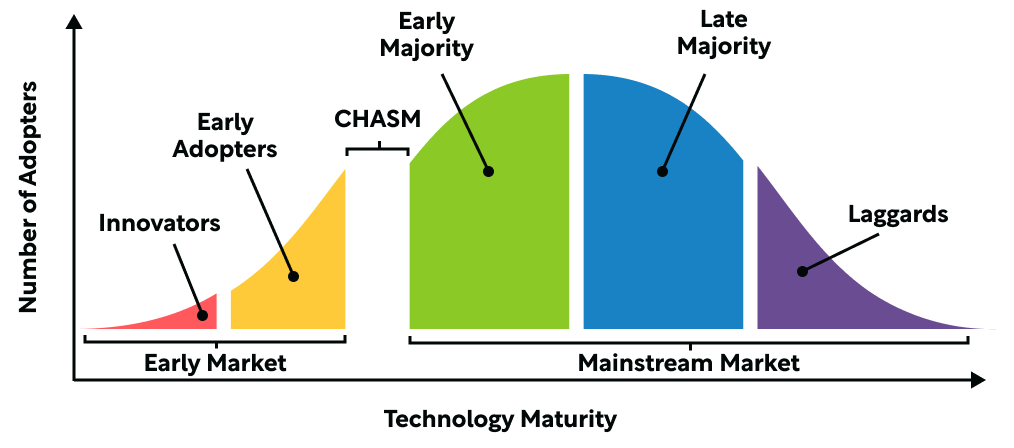

As Moore explains, the TALC predicts that as a technology matures, the number of potential new buyers first increases (as the technology starts to catch on) and then decreases (as you run out of potential customers who haven’t already bought it), following the profile of a bell curve. The area under the curve represents the total number of customers for the new technology. This area is divided into five categories of prospective customers, as shown in the figure below.

(Shortform note: This concept was originated by George Beal and Joe Bohlen of Iowa State College, who, in 1956, published studies on when farmers adopted new agricultural technologies (such as fertilizer and hybrid seed corn). Six years later, a communications professor at Ohio State University named Everett Rogers expanded upon Beal and Bohlen’s research in a book titled Diffusion of Innovations, which popularized the concept outside of the farming community and made it relevant to other industries.)

(Shortform note: Moore states that the boundaries between these five categories lie approximately at the standard-deviation intervals on the bell curve. However, the graph that he presents in Crossing the Chasm depicts the boundaries further from the center than the standard deviation intervals would be. Moore provides no explanation for this, so presumably, his graphic simply wasn’t drawn to scale. However, in our figure above, the boundaries are marked at the standard-deviation intervals.)

Psychographic Categories of Customers

The TALC model divides customers into five categories based on their “psychographics,” the combination of psychology and demographics that dictates their purchasing behavior. These categories are:

Innovators

Innovators are the first to buy new technology. According to Moore, they love new technology just because it’s new technology, but they’re often on a limited budget because they usually work highly technical jobs, rather than positions in upper management.

(Shortform note: While Moore describes innovators as having limited budgets, Beal and Bohlen assert that innovators have high net worth and are typically influential people in their communities. Perhaps the difference arises from studying them in different contexts. An engineer working in industry might have a limited budget for assessing experimental technologies, while a self-employed farmer would only be able to experiment if he had the money to do so.)

Early Adopters

Early Adopters are the second group to buy new technology. According to Moore, early adopters are usually visionary business managers: They don’t value new technology for its own sake, but they have enough technical insight to identify the strategic advantages that new technology can provide.

(Shortform note: According to Beal and Bohlen’s original characterization, early adopters tend to be younger and more highly educated than members of the early and late majority, and are the most likely category to hold public office. Moore doesn’t mention these characteristics, which again may be a function of context: In a farming community of the 1950s, a college degree would make a farmer stand out as exceptionally educated, while in high-tech industries, almost everyone has an advanced degree. So too, perhaps early adopters in rural farming communities tend to be more involved in municipal politics, while early adopters in high-tech companies tend to be more involved in corporate politics.)

Early Majority

The Early Majority are the third group to adopt new technology. According to Moore, they are pragmatic people, who are interested in leveraging new technology to improve their business, but also averse to the risks of unproven technologies. They are less technically inclined than innovators or early adopters, and they tend to measure a high-tech product more by industry standards and the product’s reputation than by direct assessment of the underlying technology.

(Shortform note: Beal and Bohlen emphasize that the early majority tend to have fewer resources than innovators and early adopters, and thus, cannot afford to take risks with unproven technology. Moore asserts not that they can afford risks less, but that they are less interested in taking risks unless they can see a clear benefit.)

Late Majority

The Late Majority are the fourth group to adopt new technology. According to Moore, they are more conservative and less technically competent than the early majority: They’re not interested in getting ahead with technology, but they don’t want to fall behind.

(Shortform note: Beal and Bohlen’s original characterization refers to this category simply as the “majority.” Perhaps, in their assessment, this group was larger than the early majority. Then again, they may just have been using the term “majority” in a cumulative sense, since after you pass the peak of the bell curve, a majority of total customers have adopted your product. The fact that Beal and Bohlen displayed their customer categories on an s-shaped cumulative distribution curve, instead of on the bell curve suggests that they may have been thinking in cumulative terms.)

Laggards

Laggards do not adopt new technology willingly. If they adopt it at all, it will be old technology by the time they do.

(Shortform note: Beal and Bohlen referred to this category as the “non-adopters.”)

The Gaps in the Technology Adoption Life Cycle

Now that we’ve discussed the TALC, we can discuss the weakness of the model that gives rise to Moore’s “chasm”.

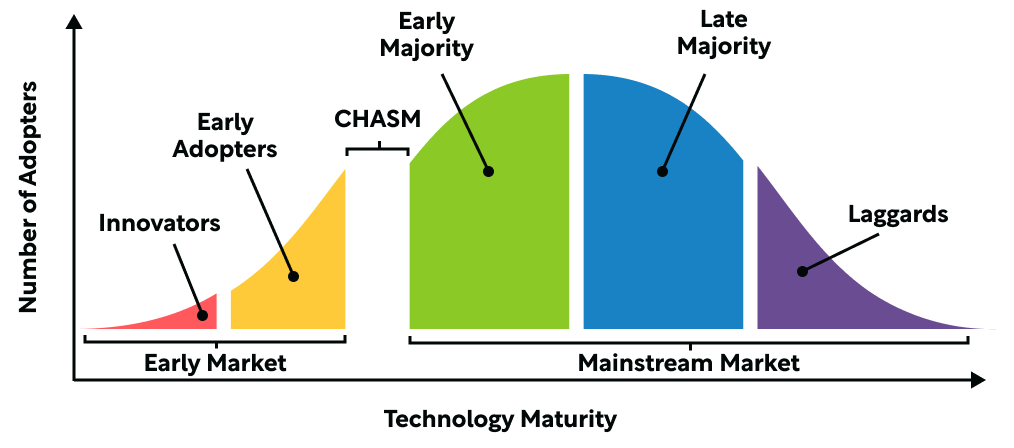

Moore explains that the traditional TALC assumes sales to the five categories of customers transition seamlessly from one to the other as the technology matures. However, according to Moore, this assumption is wrong. He argues that the psychographic differences between the people in each stage of adoption create gaps between each category. Thus, Moore proposes a “Revised TALC,” which recognizes those gaps, as shown below.

Shortform Commentary: Distinct Gaps Versus Overlapping Populations

In Moore’s revised TALC, the categories are shown as separate blocks of a segmented bell curve. However, given that Moore acknowledges you may sometimes be making sales to more than one category at once, a more accurate graphical representation of Moore’s model might represent the categories as individual, overlapping bell curves, as shown below.

The Chasm

By far the largest gap in Moore’s revised TALC is between the early adopters and the early majority. He refers to this gap as the “chasm.”

Moore explains that early adopters assess new technology at a technical level, to determine if it can give them a strategic advantage, whereas the early majority assess it based on its reputation and standardization. Because they value different things, the early majority won’t look to the opinions of early adopters when deciding whether to buy your product.

This creates a catch-22, because the early majority won’t buy your product until it has built up a good reputation in their industry, but your product can’t build up a good reputation until they start buying it and using it.

(Shortform note: Beal and Bohlen didn’t identify the chasm or discuss this catch-22 of innovation diffusion, but you can see the basis for it in their original paper: The early majority can’t afford to take risks on unproven technologies, but a new technology can’t be widely proven until they adopt it.)

The Early Market and the Mainstream Market

Moore defines the “early market” as the portion of the market made up of innovators and early adopters, and the “mainstream market” as the remaining portion of the market on the other side of the chasm.

(Shortform note: In business, the term “early market” is used mostly in this sense, and most business dictionaries cite Moore’s book as the source of the term. The term “mainstream market,” however, is also used by others to refer to any large or broadly distributed market, in contrast to a “niche market,” which is smaller and more tightly connected.)

How to Cross the Chasm

Now you understand what the “chasm” is and where it comes from, but what can you do about it?

Moore warns that you might reach the chasm quickly in your roll-out—just three to five significant sales contracts with early adopters may be enough to saturate the early market. After that, you have to enter the mainstream market. Otherwise, your sales will stagnate, and your product will die in the chasm.

(Shortform note: Moore’s estimate might be a slight exaggeration, given relative category sizes. Moore asserts that innovators make up about 2% of the market and early adopters make up about 16.7% of it. Thus, if there are only about five significant customers in the early market, who represent about 18.7% of the total, then there are only about 27 significant customers in the total market. For most products, the market probably consists of more than 27 potential significant customers, in which case there might be more than five large contracts in the early adopter category.)

How do you cross the chasm? At a high level, Moore’s strategy for crossing the chasm consists of focusing your efforts on becoming the market leader in a very specific niche market, then expanding into other niches until you dominate the market.

According to Moore, the reason this works is that it has an amplifying effect on marketing. He asserts that all marketing is ultimately dependent on word-of-mouth. Word of mouth spreads quickly through a small niche market: If just a few customers are impressed with your product, everyone will hear about it (whereas in a large market, their voices would be lost in the crowd). This is what makes it possible to build a reputation for your product and attract early-majority customers.

(Shortform note: Regis McKenna, a pioneering marketer who made his name publicizing tech companies and their products (including Apple, America Online, and Compaq), echoes Moore’s assertion that word-of-mouth is the most effective method of marketing. His premise is that word-of-mouth is an experience that turns raw information into effective communication. When a message is delivered from one person directly to another, it’s inherently tailored to the individual, increasing its impact and reducing misunderstandings. He goes on to cite the “90-10 rule,” namely that 90% of the population’s decisions are determined mostly by the influence of the other 10%.)

Moore then breaks down his strategy into four steps:

1. Choose Your Niche

Moore notes that when you first cross the chasm, you don’t have enough existing market data to choose your niche based on rational analysis, so you have to choose it based on intuition. He further observes that it’s easier to intuitively predict the behavior of a person than an abstract entity like “the market for electric cars.” Thus, he recommends creating hypothetical customer profiles and purchasing scenarios that show how each hypothetical customer would benefit from your product. Then you can select your niche by choosing the most promising of these archetypal customers.

(Shortform note: Moore is not the only one to advocate intuitive decision-making in situations like this. Malcolm Gladwell encourages you to harness the power of “unconscious thinking,” which is his term for the mental processes that make up intuition. He contrasts “unconscious thinking” with “conscious thinking,” or analytical decision making. By comparison, unconscious thinking is faster, less susceptible to stress, and less sensitive to the amount of available data.)

2. Assemble Your Whole Product

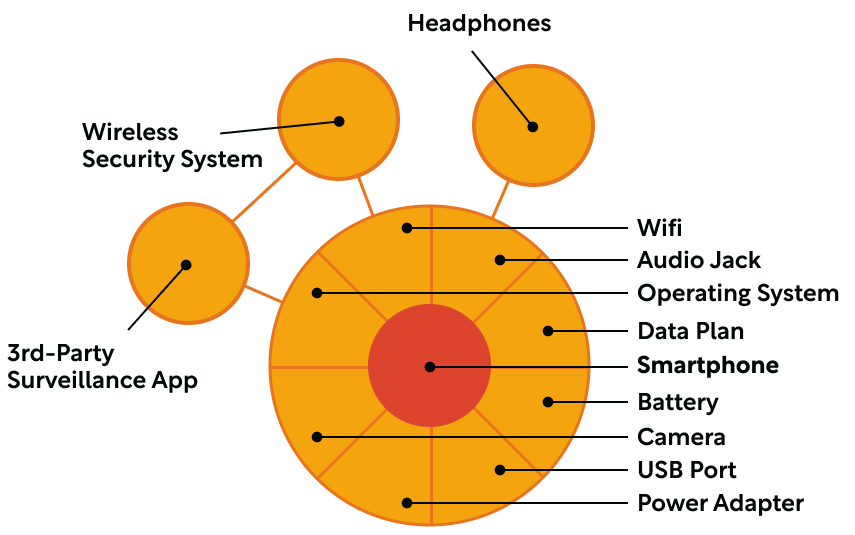

Moore refers to the complete solution that your customer wants as the “whole product,” in contrast to your core product, which only provides a central piece of the solution. For example, if you had invented the smartphone, the phone itself would be your core product, while the phone’s operating system, a data service plan, and electricity to charge the phone are all components of the “whole product.”

(Shortform note: The “whole product” concept is also called the “total product.” Most sources credit Theodore Levitt for developing the concept in his book The Marketing Imagination. However, in that book, Levitt himself attributes the concept to Harvard Business School professor Raymond Corey.)

Moore observes that to build a good reputation for your product, you need to make sure your customer can readily use it within a complete, working solution. Thus, you need to identify every component of the whole product and make sure your customer can easily access it. There are three possibilities for any given component:

- You can design your product to use elements that are already readily available, like 120 V AC electricity.

- If a component is difficult to find or install, you can bundle it with your product, like a phone that comes with the operating system already installed.

- If it’s not something readily available but also not something you want to provide yourself, you can partner with another company to deliver that part of the whole solution. For example, maybe you want to deploy a hydrogen-powered car, and you coordinate with another company that can supply hydrogen fuel and set up fueling stations for your customers.

(Shortform note: After briefly mentioning all three of these options, Moore devotes significant space to discussing corporate alliances. From this, we infer that he considers partnerships a particularly important method of supplying the whole product. Meanwhile, McKenna stresses the importance of relationships with other companies not only for supplying the whole product but also for establishing your company’s reputation by association.)

3. Position Your Product as the Market Leader in Your Niche

Moore uses the word “positioning” to describe how potential customers view a product or company and where they place it on the market landscape in relation to competing products or companies. Clearly identifying your competitors and defining your positioning claim helps to focus your marketing efforts so that customers are more likely to position your product where you want them to.

(Shortform note: In Pitch Anything, Oren Klaff recommends introducing your product with a standardized statement to the effect of “For [you target customers] who are unsatisfied with [competitor], [your product name] provides [the customer’s compelling reason to buy]. Unlike [competitor], [your product name] provides [these key features].” Moore’s theory tracks closely to this template, providing a straightforward and clear way to communicate the most important aspects of your product.)

Moore says that, to early-majority customers, the most convincing evidence of market leadership is market share. However, since you don’t have the largest market share yet, the evidence that you soon will is your commitment to delivering the whole product through alliances with other companies.

(Shortform note: Regis McKenna asserts that you can enhance your company’s reputation by associating with other companies with strong reputations. He argues that the strongest evidence for a positioning claim of market leadership is financial success (corroborating Moore’s assertion about market share), but that when you don’t yet have a proven track record of financial success, the reputation of your financial backers can be an important source of credibility.)

4. Setup Distribution

The final step in Moore’s strategy is to set up distribution so that your target customer can actually buy your product. For the purpose of distribution, he categorizes target customers according to their job titles, and advises that these different customers are more easily reached by different sales channels:

- According to Moore, Engineers are best reached by a two-phase approach: First you publish your product specifications online. Then you send sales personnel to meet with them and conduct demonstrations or facilitate testing once they express interest. This works because engineers don’t respond well to promotional marketing and typically don’t have corporate purchasing authority, but can put you in touch with their purchasing department when you demonstrate your product.

- Moore recommends reaching out to Enterprise Executives by sending your senior staff to leadership conferences where they can connect with them and develop a consultant-like relationship. He calls this “relationship marketing.”

- Moore advises cultivating relationships with Department Managers through an online system that provides basic information about your product and then connects them with a human sales representative who is also online. Managing customer relationships digitally is more efficient, which is important because department managers typically place smaller orders than enterprise executives.

- If your target customer is a Small-Business Owner-Operator, Moore recommends distributing your product through a value-added reseller (VAR). VAR’s can provide local service and support, as well as helping the customer set up the product, and educating them on how to use it, all of which small business owners tend to find particularly helpful.

- For selling to End Users, Moore recommends fully automated online self-service, with FAQ and community help forums to streamline support. This is necessary because end users typically make relatively small purchases, and so you can’t afford to spend time dealing personally with each customer.

In The Psychology of Selling, Brian Tracy identifies six types of customers, based on their psychological profiles rather than job titles: reluctant, certain, analytical, relationship-based, directive, and social.

Of the six, Tracy’s “reluctant customers” and “certain customers” correlate with the “laggards” and the “early adopters” of the TALC, while the others potentially overlap significantly with Moore’s job-title classifications. Specifically, Moore’s engineers bear a strong resemblance to Tracy’s “analytical customers,” while Moore’s enterprise executives most nearly overlap with Tracy’s “relationship customers,” as do Moore’s department managers with Tracy’s “social customers,” and Moore’s small-business owner-operators with Tracy’s “directive customers.”

Either method of categorizing customers essentially asks you to consider how certain people think and what matters to them and to tailor your approach accordingly.

Shortform Introduction

Periodically, a new high-tech innovation will transform the way we live or do business and propel its inventors to wealth and fame. More often, though, new high-tech products seem to stagnate and die instead.

In Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey Moore provides an explanation for this and presents a strategy for introducing your product effectively into the mainstream market. First, he discusses the different categories of buyers who become interested in a product at different stages of its technological maturity. Then he shows how their different perspectives create a gap, or “chasm” between the early market and the mainstream market.

Moore outlines a strategy that companies can use to move their products across this “chasm” to enter the mainstream market. He notes that his strategy is intended only for business-to-business products, as opposed to consumer products, although some of the principles he presents are applicable to consumer products as well.

Moore aimed his theories at business executives, to help them act decisively when they reach the chasm. Since the book’s publication, it has become a standard text for managers, engineers, and students, as well.

About the Author

Geoffrey Moore (not to be confused with the actor of the same name) is a marketing consultant, public speaker, and co-founder and chairman of The Chasm Group, a consulting firm. He specializes in the market dynamics of disruptive technologies and asserts that his firm has helped hundreds of companies make the difficult transition from the early market to the mainstream market.

Connect with Geoffrey Moore:

The Book’s Publication

Crossing the Chasm was first published by HarperCollins Publishers, using the Harper imprint, in 1991. A Revised edition was published in 1999, and a third edition was published in 2014. Each new edition updated the examples and case studies in the book to more recent ones, and the third edition added two appendices. This guide covers the third edition.

Crossing the Chasm was the first of seven books that Moore has written, and remains his most popular book. All his books deal in some way with the relationship between innovation and market dynamics.

The Book’s Context

Historical Context

In the latter part of the 20th century and the first part of the 21st, countless startup companies have formed around innovative high-tech products. Some of these products profoundly transform the way we live, or at least the way a certain industry conducts its business, but most of them seem to stagnate and die instead of taking off. The timely relevance of Moore’s explanation for this may have contributed to the book’s success.

Intellectual Context

Crossing the Chasm is grounded in the concept of “diffusion of innovation,” which explains how innovations are adopted by society. This concept was originated in 1956 by George Beal and Joe Bohlen of Iowa State College, who studied farmers’ adoption of agricultural technologies.

Six years later, a communications professor at Ohio State University named Everett Rogers expanded upon Beal and Bohlen’s research in a book titled Diffusion of Innovations, which was influential in popularizing the concept and making it relevant to industries beyond the farming community. Diffusion of innovations also came to be known as the “Technology Adoption Life Cycle” as the pace of technological advancement accelerated and the concept was increasingly applied to high-tech products.

In Crossing the Chasm, Moore first discusses the “Technology Adoption Life Cycle,” then points out a flaw in the model, which gives rise to the “chasm” that the remainder of the book deals with. Some sources assert that the “chasm” concept was originated by Lee James of the Regis McKenna consultant company, and there are a number of common elements between Moore’s business strategy and the strategies published by Regis McKenna in 1985.

The Book’s Impact

The success of Crossing the Chasm was unexpected. Moore notes in his foreword to the third edition that he originally estimated his target audience to consist of about 5,000 readers, specifically marketing executives in high-tech startup companies. However, the book has now sold over a million copies.

In addition to its business executive audience, it has become a reference for managers, engineers, and students. The second and third editions of the book kept its case studies up to date, and demonstrate that the ideas it presents remain influential.

The Book’s Strengths and Weaknesses

Critical Reception

As noted above, Crossing the Chasm was well received by readers. Reviewers praised the book for presenting a clear theoretical model to explain the period of transition from early to mainstream markets. Many of its more recent reviewers emphasize the book’s value as a teaching tool for industry terminology over its original purpose as a strategy guide for making the transition to the mainstream market.

However, the book was not without its critics. Some reviewers said the book was too verbose and didn’t have enough in-text citations. Others expressed concern that Moore’s strategy was oversimplified, and that Moore didn’t attribute the chasm concept to Lee James or his colleagues at Regis McKenna. More than a few reviewers complained that the book introduced too much technical jargon. Finally, some reviewers felt that the book inappropriately elevated the role of the marketing department in the hierarchy of a business.

Commentary on the Book’s Approach

The message of Crossing the Chasm is two-fold: First, it helps you understand the market dynamics that create the chasm. Then it tells you how to pilot a company across the chasm.

In explaining the theory, Moore starts by presenting the Technology Adoption Life Cycle (TALC). Then he discusses the flaw in this model, namely that it portrays the market as a continuous population of people who can be grouped according to their buying practices, when there are actually gaps between the different groups. Moore then explains how he has modified the model to make it accurate. He spends the first two chapters comparing and contrasting the original TALC with his modified version.

While this presentation is adequate, jumping back and forth between the two models can make Moore’s critique of the original model hard to follow. As evidence of this difficulty, when Seth Godin quotes Moore’s model in Purple Cow, he actually presents the original TALC, mistakenly attributing it to Moore and omitting the modification that Moore introduced to correct the model.

In explaining how to cross the chasm, Moore uses the D-Day invasion strategy of World War II as an illustration of his strategy for entering the mainstream market with an innovative product. He breaks the strategy down into four major steps, which he then elaborates upon, continually revisiting the D-Day analogy.

The D-Day analogy works well for illustrating Moore’s strategy at a high level, but like every analogy, it eventually breaks down when scrutinized in sufficient detail. Thus, as Moore elaborates on the details of his strategy, the continued references to D-Day arguably become more distracting than illustrative.

Our Approach in This Guide

Part 1 of this guide spans the first two chapters and introduces concepts that set the stage for understanding the “chasm” between the early and mainstream markets and the market dynamics that create the chasm.

Part 2 spans chapters 3-7 and presents Moore’s strategy for crossing the chasm. Specifically, chapter 3 gives an overview of his strategy, breaking it down into four steps. Each respective step is covered in more detail in one of the remaining four chapters.

In addition to providing commentary, we’ve reorganized the book’s material. In Part 1, Moore jumps back and forth between discussing the original TALC (technology adoption life cycle), his improved version of it, and strategy considerations for the early market. For clarity, we’ve separated these topics.

We’ve also added commentary comparing Moore’s presentation of the TALC with Beal and Bohlen’s original presentation and contrasting Moore’s strategy with Blue Ocean Strategy and the approach of pioneering marketer Regis McKenna.

Part 1 | Chapter 1: The Technology Adoption Life Cycle

According to Moore, there is a “chasm” between the early market and the mainstream market. Innovative products often flourish in the early market and then stagnate and die in the chasm instead of succeeding in the mainstream market as well.

To understand Moore’s strategy for crossing the chasm and entering the mainstream market successfully, you need to understand the chasm between the early and mainstream markets. And to understand the chasm, you first need to understand the Technology Adoption Life Cycle (TALC).

(Shortform note: The TALC, also known as “diffusion of innovation,” was developed by Beal and Bohlen, two agricultural extension agents working for Iowa State College in the 1950s. They developed the model based on studies of when farmers started using new agricultural innovations, such as fertilizer and hybrid seed corn. Others soon generalized the model to technological innovations outside of agriculture.)

As Moore explains, the TALC predicts that as a technology matures, the number of potential new buyers first increases (as the technology starts to catch on) and then decreases (as you run out of potential customers who haven’t already bought it), following the profile of a bell curve. The area under the curve represents the total number of customers for the new technology. This area is divided into five psychographic categories (classifications by psychological and demographic criteria) of prospective customers, as shown in the figure below.

Measuring Technological Maturity

Technology does not become more mature by itself. It takes investment in R&D to refine it. This is why the horizontal axis of the TALC graph is “technological maturity,” and not simply time.

How do you measure technological maturity? There are a number of metrics that can be used to quantify it, of which the most common is the “Technology Readiness Level,” or TRL system. That said, the TRL system only partially overlaps with the scale of technological maturity shown in the TALC:

TRL-1 through TRL-3 denote levels of preliminary scientific research and development. At this point, there is no product to sell, so this region of technological maturity lies completely to the left of the TALC curve.

TRL-4 through TRL-6 represent stages of laboratory R&D, component development, and proof-of-concept prototype testing. It is possible that you might work with a few innovators outside the company (under an NDA) during this period, but even at TRL-6 your product is only ready for preliminary proof-of-concept demonstrations. Thus, the technology maturity scale on the TALC graph starts at about TRL-6.

TRL-7 and TRL-8 represent increasingly sophisticated prototypes, such as beta versions that you might sell to innovators or demonstrate to early adopters to get an order for a custom solution tailored to their application.

The official TRL system ends at TRL-9, which denotes a technology that has been used successfully in the field. Thus, by the time you have completed your first full system installation for an early adopter, your product should be at TRL-9.

Perhaps the TRL-system could be extended to cover the rest of the TALC. For example:

TRL-10 could denote the point where the technology is recognized in industry standards. On the graph, this would be near where the early majority section begins.

TRL-11 could denote widespread proliferation of the technology, or more precisely, the point under the peak of the curve, where at least half of the potential customers have already adopted it.

TRL-12 could denote the point where the technology is considered essential for routine operations in its applicable context. On the graph, this would be in the laggard region.

Category Boundaries

Moore states that the boundaries between these five psychographic categories lie approximately at the standard deviation intervals on the bell curve. (Most of the area under a normal bell curve lies within three standard deviations of the center, so in this case, the standard deviation intervals essentially divide the graph into six equally spaced regions along the horizontal axis.)

However, the graph that Moore presents in Crossing the Chasm depicts the boundaries considerably further from the center of the curve than standard deviation intervals would be. This makes the early and late majorities appear to represent a larger proportion of the overall population. Moore provides no explanation for the discrepancy in the graph, so presumably, his graphic artist simply didn’t draw it to scale.

In our figure above, the boundaries are marked at the standard deviation intervals, consistent with Moore’s assertion. However, other analysts have challenged the proportions of the population allotted to each category. Some argue that with the accelerating pace of technological innovation, the peak of the bell curve has shifted to the left, meaning that today there are proportionately more people in the early majority and early adopter categories, and fewer people in the late majority.

In the remainder of this chapter, we'll discuss the characteristics of the people in each category in terms of their population size, motive for buying new technology, technical competence, quality requirements, price sensitivity, perspective on the whole product, and perspective on product positioning.

(Shortform note: Moore’s strategy is intended specifically for business-to-business marketing, so he depicts the people of each category in this light, though others have applied the TALC concept to individual consumers as well.)

However, to understand the two final characteristics, you first need to understand the “whole product model” and the concept of “positioning” as Moore uses these terms.

The Whole Product Model

As Moore explains, the premise of the “whole product” concept is that a product has to interface with other products, services, or infrastructure in order to perform its intended function. For example, if you buy a smartphone, your “whole product” might consist of the phone itself plus a data plan, electricity to charge the phone, and some third-party apps.

(Shortform note: The “whole product” concept is also called the “total product.” Most sources credit Theodore Levitt for developing the concept in his book The Marketing Imagination. However, in his book, Levitt attributes the concept to Harvard Business School professor Raymond Corey. Moore introduces a “simplified whole-product model” that differs from Levitt’s model, as we will discuss in Chapter 6.)

The Concept of Positioning

Moore uses the word “positioning” to describe how potential customers view a product or company and where they place it on the market landscape in relation to competing products or companies.

He also uses it to describe what you do to help customers establish your product’s positioning. However, he emphasizes that positioning is ultimately determined by the customers, not the company. For example, you could run a great advertising campaign extolling the reliability of your product, but if customers encounter problems with it, then people may still regard it as an unreliable knock-off.

(Shortform note: The term “positioning” is used differently by different sources. For example, one online business glossary defines product positioning as the process by which you identify the critical function your product will perform for your prospective customers and communicate it to them. Another defines it similarly and emphasizes that the key to doing this is understanding your customers. While Moore’s perspective still prompts these kinds of actions, his definition contrasts with these definitions at a theoretical level, because he insists that positioning ultimately takes place in the customer’s mind, not in your marketing department.)

Innovators

The first category of customers represented in the TALC is made up of “innovators.” Moore also calls them “technology enthusiasts,” or “techies,” because they value innovative technology for its own sake. They buy new or experimental products just to try them out because they want to be on the cutting edge and participate in advancing the state of the art. Moore characterizes innovators as follows:

- Population size: About 2% of the total population.

- Technical Competence: Extremely high. Moore observes that innovators can get by with minimal operating instructions, and they’ll often invest their own time in debugging your product.

- Quality Requirements for your product: Low. They are used to working with products that don’t have all the bugs worked out of them yet.

- Price Sensitivity: High. Moore notes that innovators typically operate on a limited budget, and some of them believe that technology should be free or provided at-cost. (Shortform note: It seems likely that most innovators would be in technical rather than executive roles in a company. This would limit their budget and their ability to place large orders for their company, consistent with Moore’s characterization.)

- Whole-Product Perspective: Innovators don’t need whole products, because they take pleasure in assembling components into working systems for themselves.

- Product Positioning Perspective: According to Moore, innovators assess your product’s positioning on a purely technical basis. To help them evaluate where it fits relative to other technology, they look for schematics, demonstrations or user trials, and endorsements from respected technology gurus. They tend to communicate broadly, both within and outside of their own industry or community, to keep abreast of new technological developments.

Beal and Bohlen’s Perspective on Innovators

According to Beal and Bohlen’s original characterization, innovators, by definition, are the first people in their respective communities to adopt new technology.

They report that there are usually only one or two of them in a local community, corroborating Moore’s assessment of their population size.

Beal and Bohlen report that innovators typically have high net worth, and most importantly, they have large amounts of “risk capital.” They can afford to buy new technology just to try it out. This contradicts Moore’s assertion that innovators are more price-sensitive. Perhaps the price sensitivity of innovators is context-specific. An engineer working in industry might have a limited budget for assessing experimental technologies, while a self-employed farmer would only be able to experiment with new agricultural technologies if he had the money to do so.

According to Beal and Bohlen, innovators are typically influential people in their communities, with many connections outside their local community as well. This description corroborates Moore’s assertion that innovators tend to communicate broadly.

Early Adopters

The second category consists of “early adopters.” Moore prefers to call them “visionaries,” because most of them are ambitious leaders looking to gain a strategic advantage or make a quantum leap forward by leveraging new technological breakthroughs. Unlike the innovators, they are not interested in new technology for its own sake, but rather in the new advantages it may afford.

- Population size: About one-sixth of the population.

- Technical Competence: High. Moore observes that a typical early adopter has the technical insight to identify and implement strategic technologies, as well as the charisma to rally his company around the project.

- Quality Requirements for your product: Moderate. Moore describes early adopters as being comfortable accepting the risk of unproven technology because they envision it providing great benefits. However, he also notes that their expectations often exceed the product’s actual capabilities, making them difficult customers to please in the long run.

- Price Sensitivity: Lowest. Moore asserts that early adopters are usually corporate executives with resources to fund ambitious projects.

- Whole-Product Perspective: According to Moore, early adopters are willing to take responsibility for assembling the whole product because they want to be the first to leverage its capabilities.

- Product Positioning Perspective: According to Moore, early adopters assess your product’s positioning based on how it fits into their vision for the future or could help them realize their ambitions. They communicate broadly to keep an eye out for new technologies with strategic applications and evaluate them based on technical benchmarks, product reviews, initial sales metrics, and trade press coverage.

Beal and Bohlen’s Perspective on Early Adopters

According to Beal and Bohlen’s original characterization, early adopters tend to be younger and more highly educated than members of the early and late majority. They are well-read and stay well-informed, receiving more technical or agricultural publications than the majority do.

Moore echoes Beal’s assertion that early adopters are well-informed and communicate broadly, especially through publications, but he does not address their average age or level of education. Perhaps these characteristics were more pronounced in the population that Beal and Bohlen studied.

For example, perhaps in a farming community, the average farmer has a two-year degree or equivalent, while early-adopter farmers have graduate-level degrees. Meanwhile, the average office worker of a Silicon Valley manufacturing company has a graduate-level degree, and so highly-educated early adopters don’t stand out as being significantly more educated than the rest of the population.

Beal and Bohlen state that early adopters are also the most likely to hold public office or otherwise be formally involved in the institutions of their respective communities. Moore makes no mention of this but does say that early adopters usually hold executive positions in their respective companies. Perhaps early adopters in rural farming communities tend to be more involved in municipal politics, while early adopters in advanced manufacturing companies tend to be more involved in corporate politics.

After commenting that innovators tend to have large amounts of risk capital available, Beal and Bohlen offer no comment on the financial status of early adopters. This contrasts with Moore’s description, since Moore identifies early adopters as having the most funding available to spend on cutting-edge technology, while innovators are much more price sensitive.

Early Majority

The third category is made up of the “early majority.” Moore prefers to call them “pragmatists,” because they are interested in taking advantage of new technology, but they’re also averse to the risks of pioneering a new technology.

- Population size: About one-third of the population. Moore identifies them as the largest of all the categories.

- Technical Competence: Moderately high. According to Moore, they are willing and able to learn how to use new technology, but they expect good documentation and technical support.

- Quality Requirements for your product: High. Moore observes that they’re not interested in buying a product until it’s fully debugged. Moreover, they only buy from companies that have established a reputation for delivering a high-quality product and standing behind it.

- Price Sensitivity: Moderate. Typically they are looking for good value at the upper end of the performance spectrum.

- Whole-Product Perspective: According to Moore, the early majority will only buy your product if they can’t see that everything they need to benefit from it is readily available. They consider whole-product features such as compatibility and long-term support when evaluating the quality of your product.

- Product Positioning Perspective: According to Moore, the early majority assess your product’s positioning based on how it compares to alternatives. They tend to communicate narrowly within their own industry. To assess where your product fits into the landscape of their industry, they consider your market share, the industry standards or certifications that your product meets, press coverage, and endorsements from other users within their community.

Beal and Bohlen’s Perspective on the Early Majority

According to Beal and Bohlen’s original characterization, members of the early majority tend to have fewer resources than innovators and early adopters, such that they cannot afford to take risks with unproven technology. Thus, when a new innovation comes out, they wait until they can be sure it works before they adopt it.

Moore echoes this perspective but emphasizes that the early majority tend to base their evaluation of products heavily upon the reputation of the manufacturer and/or distributor.

Beal and Bohlen further observe that early adopters tend to be slightly more educated than the general population. Again, Moore does not mention education as a distinguishing characteristic of this group. As we discussed in the case of early adopters, the educational difference may have been more pronounced for the farming population that Beal and Bohlen were studying than for the industrial customers that Moore describes.

According to Beal and Bohlen, the early majority tend to be “informal leaders'' in their communities, in the sense that they do not hold public office or other positions of formal leadership, but their peers admire them and respect their opinions. They tend to place a high value on their peers’ respect and are careful to maintain their reputation. They tend to communicate closely within their own community, but not outside of it.

These observations corroborate Moore’s assertions about the close-knit nature of early majority communities, whether rural or industrial, and the value that the early majority place on reputation. Although Beal and Bohlen don’t explicitly extend the importance of reputation to the manufacturer or distributor as Moore does, their description of the early majority makes this a natural extrapolation.

Moreover, as we will see in the next chapter, these two qualities play a pivotal role in generating the “chasm” between early adopters and the early majority. Beal and Bohlen did not identify Moore’s “chasm,” but it arguably could be identified based solely on analysis of their original characterizations of the different categories of adopters.

Late Majority

The fourth category is made up of the “late majority.” Moore prefers to call them “conservatives,” because they tend to value stability over progress. They are not interested in new technology or the advantages it affords, but as it becomes standard and the technology that it replaces becomes obsolete, they will eventually upgrade to mitigate risk.

- Population size: About one-third of the population. More says they are almost as numerous as the early majority.

- Technical Competence: Moderately low. Moore says they tend to value simplicity and convenience over performance because they are less confident than the early majority in their ability to implement new technologies.

- Quality Requirements for your product: High. Moore observes that they require a product that is well-proven, thoroughly debugged, and widely supported across the industry.

- Price Sensitivity: High. As Moore points out, the early majority aren’t willing to spend much on new technology because they don’t expect to benefit from it.

- Whole-Product Perspective: According to Moore, the late majority are even more sensitive to missing parts of the whole product than the early majority are, because they are less competent at putting together the whole product.

- Product Positioning Perspective: Moore asserts that, because they value stability, the late majority tend to assess your product’s positioning based on how long they think it will be supported. To evaluate this, they consider its performance in industry to date, who else is using it, who is distributing and supporting it, and analysis provided by the business press.

Beal and Bohlen’s Perspective on the Late Majority

Beal and Bohlen’s original characterization refers to this category simply as the “majority,” rather than the “late majority.” Perhaps, where Moore identified the late majority as being slightly smaller than the early majority, Beal and Bohlen saw it as being slightly larger.

Then again, their nomenclature could also be a product of their method of analysis. When your product passes the peak of the bell curve into the region of the late majority, that implies that more than half of the total customers have adopted it. Thus, in a cumulative sense, selling to the late majority means your product has been adopted by the majority of the market. Beal and Bohlen displayed their customer categories on an S-shaped cumulative distribution curve, instead of on the bell curve that other analysts, such as Moore, used later. This could imply that they applied the term “majority” to the late majority in a cumulative sense.

In any case, Beal and Bohlen describe the late majority as typically being older and less educated than members of the preceding categories. They also describe them as less likely to read technical publications, hold positions of leadership within their communities, or communicate outside of their own community.

Their observations about technical publications and leadership positions is consistent with Moore’s assertion that they tend to be less technically competent and less confident in their ability to implement new solutions.

Moore does not discuss the relative age of the different categories. It may be that age became less relevant between the time of Beal and Bohlen’s research and the time of Moore’s writing. Perhaps generations that had experienced periods of technological stasis were more likely to be late adopters. Then, as the pace of technological advancement accelerated and the generation that was old enough to remember times of technological stasis died off, age would have ceased to be a defining quality of the late majority.

Laggards

The fifth category is made up of the “laggards.” Moore also calls them “skeptics,” because they tend to be skeptical of new developments and often criticize new technologies publicly. In their view, every new technology introduces new risks, and the alleged benefits of new innovations simply aren’t worth the risks.

- Population size: About one-sixth of the population.

- Technical Competence: Low. Moore asserts they are either unable or unwilling to learn how to use new technologies.

- Quality Requirements for your product: Very High. They probably won’t buy your product, but as it proliferates throughout the industry, they are adept at identifying discrepancies between your marketing claims and actual performance.

- Price Sensitivity: Not applicable, since they’re not likely to buy new technology at any price.

- Whole-Product Perspective: Not applicable, since they avoid implementing new technologies.

- Product Positioning Perspective: Moore does not describe how laggards assess the positioning of your product. However, from what he does say, we may infer that they tend to position products and companies based on risk, and they tend to assess the risk primarily based on product history, especially their own usage history or that of their immediate colleagues.

Beal and Bohlen’s Perspective on Laggards

Beal and Bohlen referred to this category as the “non-adopters.” They describe them as being the oldest, the least educated, and the least likely to read technical publications.

Moore does not characterize laggards in terms of age or education, per se. The age factor might have been less significant by the time of Moore’s writing, as we discussed in the case of the late majority. Moore identifies them as unable or unwilling to learn new technologies, which seems consistent with a lower level of education, even though Moore doesn’t bring it up.

Then again, Moore also notes that laggards tend to express criticism of new technologies and point out discrepancies in marketing claims. In order to do this, they would need some level of familiarity with both the technological basis of the product and the publications where it is advertised.

This dichotomy suggests that perhaps laggards are a more diverse category, or are not as thoroughly characterized as the other categories. The unifying characteristic of the laggard category is that they resist adopting new technologies, but perhaps different laggards have different motives. Neither Beal and Bohlen nor Moore spend much time discussing laggards, and it stands to reason that they have been studied less, because they are not regarded as having the potential to generate significant sales. Why spend time and money trying to understand a group that won’t buy your product anyway?

Exercise: What’s Your Psychographic Category?

Recall the psychographic categories of the TALC (technology adoption life cycle):

- Innovators love new technology for its own sake.

- Early adopters want to gain an advantage with new technology.

- The early majority look to how others around them feel about a new technology.

- The late majority want to keep up with the status quo.

- Laggards are skeptical.

Think of the last time you bought (or downloaded, subscribed to, etc.) a high-tech product, such as a new software program, an electronic gadget or other tool you didn’t have before, or a medical treatment/drug that recently became available. What did you purchase, and what were your motives for buying it? Which category do you think you were in when you made that purchase?

Think of an advertisement you’ve recently seen for something that you’ve decided not to buy, at least for now. What was the product or service? What were your motives for deciding not to get it? Which category does this put you in for this situation?

Chapter 2: The Gaps in the Technology Adoption Life Cycle

We have discussed the TALC (Technology Adoption Life Cycle). Now we’re ready to discuss the flaw in the TALC model that gives rise to Moore’s “chasm.”

Moore explains that the traditional TALC assumes that sales to the five psychographic categories of customers transition seamlessly from one to the other as the technology matures. Sales in earlier categories build momentum, prompting adoption in the next category. This matters because maintaining sales momentum is the key to success.

(Shortform note: In The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell expresses precisely this sentiment. He argues that the key to making an idea or product wildly successful is to build momentum until it reaches the “tipping point,” or “critical mass,” after which popularity growth becomes self-sustaining. Gladwell does not discuss the TALC, per se, as his book does not focus specifically on innovative technological products, but his book nevertheless provides an example of the emphasis that marketers place on building momentum when promoting an idea or product in a contiguous population.)

However, according to Moore, the categories don’t transition smoothly and immediately from one to the next. He argues that the psychographic differences between the people in each stage of adoption create gaps between each category. Thus, Moore proposes a “Revised TALC,” which recognizes those gaps, as shown below. Because of the gaps, sales momentum in one category doesn’t necessarily carry over to the next. To illustrate this principle in more detail, we’ll devote the remainder of this chapter to discussing how the characteristics of each category generate each of the gaps.

Shortform Commentary: Distinct Gaps Versus Overlapping Populations

On the traditional TALC, the category boundaries divide a single population into contiguous groups. In Moore’s revised TALC, the categories are now shown as separate blocks of a segmented bell curve. However, a more accurate graphical representation of Moore’s model might represent the categories as individual bell curves, as shown below.

This is because the timing of purchases from customers in one category can sometimes overlap with those from another category. For example, you might have a far-sighted early adopter who can see the advantages of a new technology even though the technology is still in its infancy. You might also have some innovators who must wait until a product reaches a certain level of maturity before they are able to adopt it, because of limited equipment or expertise. In this case, some early adopters might actually buy the product (or fund further development) at a lower level of maturity than some of the innovators.

This implies that the innovator and early adopter populations overlap on the technological maturity scale if we define the categories based on attitude toward new innovations. Similarly, other categories could overlap as well. In discussing marketing strategies for the different categories and how to transition between them, Moore acknowledges that you may sometimes be selling to multiple categories at once.

Gap #1: The Application Gap Between Innovators and Early Adopters

Recall that, according to Moore’s characterizations, innovators value innovative technology for its own sake, while early adopters only value the benefits that innovative technology affords. Thus, the gap between innovators and early adopters represents the difference in technological maturity between presenting a new technology and showing that the new technology could actually be useful for something.

Moore notes that this gap is relatively small because early adopters tend to rely on innovators as references. Thus, if the innovators like your product, and the early adopters can think of beneficial uses for it, then this gap is easy to cross.

Symptoms of Reaching the Application Gap

How would you detect that your product has reached this gap? Moore doesn’t address this directly, but we can infer that the primary symptom of this gap would be feedback from prospective customers along the lines of, “That’s an impressive invention you’ve got, but what’s it actually good for?”

Gap #2: The Chasm Between Early Adopters and the Early Majority

The most significant gap is what Moore calls the “chasm” between early adopters and the early majority. The gap is wide enough that Moore presents it as separating the population into two different markets: The “early market” is made up of innovators and early adopters, while the “mainstream market” is composed of the early majority, late majority, and laggards.

(Shortform note: In business, the term “early market” is used mostly in this sense, and most business dictionaries cite Moore’s book as the source of the term. The term “mainstream market,” however, is also used by others to refer to any large or broadly distributed market, in contrast to a “niche market,” which is smaller and more tightly connected.)

As Moore explains, early adopters are eager to adopt unproven cutting-edge technology because they want first-mover advantage, while the early majority want to mitigate the first-mover risk by waiting until the technology is well proven and well supported. The early majority also tend to rely on industry standards as a means of managing risk, and thus tend to favor industry-standard products.

Therefore, as Moore explains, early adopters tend to base their buying decisions on the perceived benefits of the product itself, while the early majority place more weight on the reputation of the manufacturer and/or distributor. Early adopters also communicate broadly with each other and with innovators, so they can reference innovators’ impressions of your product, but the early majority communicate more narrowly within their own community or industry, so they are unlikely to reference the impressions of innovators or early adopters.

Symptoms of Reaching the Chasm

The characteristic symptom of the chasm that Moore repeatedly cites is stagnant sales: When you first release your product, you may see exponential growth of sales in the early market, but then sales revenue hits a plateau or even trails off as the early market saturates and you enter the chasm. This is probably the symptom that drove most of Moore’s clients to seek his help in crossing the chasm, so it is understandable that he would cite it.

However, from Moore’s description of the chasm, we can infer other symptoms as well. One symptom could be that coverage of your product in technology-oriented media sources has trailed off (because it’s no longer new enough to be technologically sensational) while business-oriented media sources aren’t interested in covering it yet (because your product or company doesn’t have enough market share to seem worthy of their attention).

Another symptom could be increased inquiries about installation support, or availability of parts of the whole product besides the core technology that you supply. Recall that, when they purchase the core technology, early adopters are usually willing and able to take ownership of assembling the whole product, whereas the early majority expect the whole solution to be readily available.

Thus, if you’ve run out of early adopters, such that most of your prospective customers are now from the early majority, they’ll be asking questions about the availability of the whole product (and not placing an order, when they find out you can’t supply the whole solution, leading to the stagnant sales we discussed earlier).

Similarly, if a prospective customer asks whether your product meets certain industry standards or has certain certifications, that likely means the prospect is a member of the early majority. And if a high percentage of your prospects are asking these types of questions, that could be an indication you’ve run out of early adopters and have reached the brink of the chasm.

The Catch-22 of the Chasm

According to Moore, the early majority won’t be comfortable buying your product until you build up a good reputation among other members of the early majority in their industry, but you can’t build up a reputation with them until they buy your products. By the same token, the early majority prefer to buy industry-standard products, but your product can’t become the industry standard until the early majority adopt it. This creates a catch-22 situation that makes it difficult to move your product across the chasm.

(Shortform note: Beal and Bohlen didn’t identify the chasm or discuss this catch-22 of innovation diffusion, but you can see the basis for it in their original paper: The early majority can’t afford to take risks on unproven technologies, but a new technology can’t be widely proven until they adopt it.)

Gap #3: The Competence Gap Between the Early and Late Majority

According to Moore, the gap between the early and late majorities is relatively small and is driven by their differing levels of technological competence. Specifically, the late majority are less confident in their ability to learn and implement new technologies, so they need solutions that are more user-friendly. Thus the gap between these two categories divides people who need more support (late majority) from people who need slightly less (early majority—although they still need more support than the early adopters).

Symptoms of Reaching the Competence Gap

Moore doesn’t explicitly address how you identify when you’ve reached this gap, but once again we can infer some symptoms from his description. For one thing, based on the size and distribution of the categories, you won’t hit this gap until your product is the market leader, with about 50% of the market share.

Another symptom could be a sharp uptick in the demand on your tech support department, as more customers with less technical competence start buying your product. Yet another symptom could be if you detect an assimilation gap: People are buying your product because of pressure to keep up with industry standards, but they aren’t actually using it, or aren’t taking advantage of its full capabilities.

Gap #4: The Gap Between the Late Majority and the Laggards

Moore does not discuss the gap between the late majority and laggards, although he does show this gap on his revised TALC figure. Presumably, he did not consider this gap worthy of discussion because crossing it has little bearing on the success of a company or product: The gap is small and the laggards offer limited sales potential anyway.

However, he does mention in passing that one of the few ways to sell new technology to laggards is to integrate it into something they already use without their realizing it.

For example, maybe you’ve developed a smart stock tank for ranchers that uses a microprocessor and an electronic valve to keep the water trough at a certain level, and allows the rancher to monitor water levels across all his tanks from his smartphone. The laggards want nothing to do with your new system: they will stick with their old-fashioned stock tanks that use mechanical float-activated valves. However, if you develop a model with a lifetime battery that can be deployed just like a regular mechanical stock tank, your distributor may be able to sell it to laggards as a “plain old self-filling stock tank,” even though it uses your electronic valve system and has wifi capabilities that they don’t realize and won’t use.

Thus, we might infer that the gap between the late majority and the laggards is one of visibility: To cross the gap into laggard territory, the technology has to mature to the point where it doesn't look like a new technology anymore. If it looks just like the same old thing that everybody’s been using all along, then the laggards may cease to be averse to it.

Part 2 | Chapter 3: High-Level Strategy

In the first two chapters, we discussed Moore’s explanation of the technology adoption life cycle (TALC), and how the gaps in the TALC create a chasm between the early market (innovators and early adopters) and the mainstream market (early majority, late majority, and laggards).

In this chapter, we’ll first discuss Moore’s general strategy for succeeding in the early market. Then we’ll consider Moore’s argument for why a company must cross the chasm, after which we’ll present an overview of Moore’s strategy for crossing the chasm, which uses a metaphor based on the World War II D-Day invasion to discuss focusing on a niche market.

Moore’s strategy can be broken down into four main steps, which we’ll elaborate on in the next four chapters: choose your niche, provide a whole product, position your product, and set up distribution.

Early Market Strategy

According to Moore, the best-case scenario for a high-tech startup to sell to the early market follows approximately this chronology:

- You develop a breakthrough technology with at least one compelling application.

- You show it to tech-savvy innovators, who agree it is revolutionary.

- You connect with early adopters and help them see how your product could transform their industry.

- The early adopters consult the innovators who’ve already adopted your product.

- The innovators back up your claims, resulting in a major project contract with an early adopter.

- You use the funding from the first major project to refine the product for the customer’s application and generate a few marketable spinoff products in the process.

- You continue selling your product to early adopters until the early market starts to saturate.

It’s worth noting that Moore’s best-case chronology is just that: a chronology rather than a strategy. It depicts how your business should ideally develop in the early market, but, by itself, doesn’t tell you how to achieve this ideal.

For example, how do you develop a breakthrough technology? That’s beyond the scope of Crossing the Chasm, although Charles Duhigg addresses it to some extent in Smarter, Better, Faster. Similarly, how do you make sure that the innovators agree your product is revolutionary? We may infer that you do this by first making a technological breakthrough, and then marketing and positioning your product in ways that appeal to innovators as a psychographic group, but Moore doesn’t provide much specific advice on this issue. The same applies to most of the other steps in the chronology. Thus, while the best-case chronology gives you something to aim for, you may need additional resources to develop a comprehensive strategy for the early market.

Early Market Problems

However, Moore acknowledges that in real life things don’t always work out according to the best-case scenario. He offers solutions to a few common problems that can come up in the early market phase.

Problem: You don’t raise enough capital up front to fully develop your product for the entire market of early adopters.

According to Moore, the solution is to scale back your expectations and focus on a smaller set of customers with more specific needs. This reduces development and marketing costs by narrowing the scope of both technical development and marketing.

(Shortform note: If you have a compelling innovation, and just need more money to finish development or adequately market it, presumably another solution would be to ask your financial backers for additional capital, or appeal to additional investors. In Pitch Anything, Oren Klaff argues that the key to persuading investors to back you is controlling their frame of mind by packaging your ideas correctly and knowing how to maintain a psychologically dominant position.)

Problem: You sign a contract with an early adopter before you have developed your product enough to deliver on it.

Moore says that solving this problem requires a three-pronged approach: First, you shut down marketing, since there’s no point looking for new customers when you don’t even have the resources to deliver products to the one you have. You also confess any exaggerated claims to your customer and scale back your promises as much as possible. Then, you focus all your resources on product development to meet the remaining deliverables of your contract.

(Shortform note: A contrasting school of thought argues that by over-committing, you can actually become a brand leader. While this theory might not advocate the kind of contractual over-commitment that Moore deals with here, the strategy is functionally similar: First, you commit to delivering something extraordinary, then you focus all your resources on actually delivering it.)

Problem: You can’t articulate a compelling application for your product.

According to Moore, the solution to this problem is to reevaluate whether you have actually made a technological breakthrough.

If you have, he directs you to focus on developing and marketing one specific application.

(Shortform note: This implies that your real problem is you’re not communicating your product’s application clearly because you’re trying to promote too many possible applications at once. The “strategy canvas” developed by Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne in Blue Ocean Strategy could be a useful tool for determining which application to pursue: Plot the value of your product’s features for a given application, and then plot the top few competing products on the same chart, giving you a visual of how much unique value your product or idea provides in that application. The charts would help you choose the application that provides the most unique value.)

If you haven’t actually made a true breakthrough, Moore suggests presenting your product as a supplement to some existing technology.

(Shortform note: Presumably you would only do this after first identifying a compelling way in which your product complements existing technology. Once again, the strategy canvas could be useful for identifying the unique value your product provides as a supplementary product in a given application.)

Why You Must Cross the Chasm

Having mastered selling your product in the early market, it might be tempting to stay there, but Moore says this is not an option. He estimates that three to five significant contracts with early adopters will saturate the early market. After that, your sales will stagnate unless you start attracting early major customers.

(Shortform note: This might be a slight exaggeration, given relative category sizes. Moore asserts that innovators make up about 2% of the market and early adopters make up about 16.7% of it. Thus, if there are only about five customers in the early market, who represent about 18.7% of the total, then there are only about 27 customers in the total market. For most products, the market probably consists of more than 27 potential customers, in which case there might be more than five early adopters.)

Moore also asserts that you make most of your profits in the mainstream market, because that’s where the majority of customers are.

(Shortform note: To quantify this, if we assume the early and late majorities each make up a third of the total market, we might initially estimate that the mainstream market makes up about two-thirds of your total sales. However, some sources claim that in recent years, the distribution of the categories has shifted, such that the early majority now makes up a larger fraction of the population.)

Dangers of the Chasm

Moore advises crossing the chasm decisively as soon as you reach it, because while you’re in the chasm, your company is vulnerable to a number of dangers.

For one thing, Moore warns that your success in the early market has made competitors aware of your product. If they’ve lost a few early-adopter sales contracts to you, they will be looking for ways to reclaim their market share.

(Shortform note: Moore doesn’t go into detail about what this focused competition looks like, but George Stalk and Rob Lachenauer discuss this kind of “hardball” competition at length. Perhaps, given enough time, your competitors will reverse-engineer your product and copy it or even develop a new version of it that gives them a competitive advantage. Perhaps they’ll focus advertising efforts on highlighting your product’s shortcomings, relative to theirs, or use other so-called “competitive blunting” tactics to avoid losing market share to your product.)

For another thing, Moore notes that your financial backers have seen your success in the early market, and they are excited about your revenue growth. As the early market saturates and sales stagnate, they become worried that something is wrong with your company. Some may even take advantage of the situation to drive down your stock value so they can buy up a controlling interest in your company and make sweeping changes. Moore calls the latter “vulture capitalists.”

(Shortform note: The term “vulture capitalist” is widely used in business to refer to any venture capitalist who buys up companies when they hit rock bottom, implements draconian measures to turn them around, and then sells them at profit.)

Products That Died in the Chasm

To further drive home the dangers of the chasm period, Moore discusses the Segway, a personal transportation device which, according to Moore, failed to break into the mainstream market because it couldn’t navigate stairs. He likewise cites Motorola’s Iridium network, a satellite phone system that never caught on with mainstream customers because it had poor signal reception indoors.

However, the technical nature of these product failures begs the question of whether they actually died in the chasm, or before they even got there. Recall that, according to Moore, one of the key distinctions between the early and mainstream markets is that early-market customers evaluate a technology based on its own technical merit, whereas mainstream-market customers evaluate it mostly based on reputation and market share.

Thus, if a product fails due to publicized technical limitations, such as the inability of a mobility device to climb stairs, or a phone’s poor reception, it seems likely that it was still in the early market at the time of its demise. If Segway failed because it couldn’t climb stairs and Iridium failed because its signal couldn’t penetrate walls, then it would appear that both these products died before they reached the chasm.

Other Perspectives on Segway’s Failure

In the case of the Segway, others have offered a variety of explanations for its failure in the market. For one thing, there is an active market for scooters and bicycles and similar transportation devices that don’t climb stairs. However, rather than competing for a share of the scooter market, Segway presented its product as an alternative to walking. Arguably, it was only this marketing decision that made stairs a problem for the Segway.

So, why didn’t the Segway company just pivot its marketing strategy, and take over the scooter market?

For one thing, their product retailed for about $5,000, which was roughly 10 times more than a motorized scooter, and 100 times more than a non-motorized scooter. The price alone put it out of reach of a large percentage of scooter buyers.

The Segway also looked different from other scooters, and became a punchline for making its users look like “dorks.” This further narrowed the potential customer base.

Furthermore, the safety of the Segway was called into question, particularly after the owner of the company accidentally ran his Segway off a cliff and died in the crash.

In the end, it appears Segway was unable to identify any compelling application where none of these concerns would have been show stoppers. Thus, the Segway may actually have died in the application gap, rather than the chasm: A few innovators thought it was cool, but it wasn’t practical enough to attract early adopters.

Strategy for Crossing the Chasm