1-Page Summary

In business, as in life, the only thing certain is uncertainty. How, then, can companies survive—even thrive—when the future is unpredictable? Using data from over 7,000 historical documents, Great by Choice authors Jim Collins and Morten T. Hansen shed some light on how some companies can weather great adversity better than others.

From an initial list of 20,400 companies, the research team identified seven case studies that they dubbed “10X” companies—those that performed better than the industry average by at least 10 times during periods of upheaval. To get a clearer idea of what these high-performing companies did differently, the research team also identified a comparison company for each 10X company. These comparison companies didn’t perform quite as well, despite being in the same industry, in the same era, with opportunities similar to those of the 10X companies.

The 10X companies (and their comparison companies in parentheses) are:

- Amgen (comparison company: Greentech)

- Biomet (Kirschner)

- Intel (Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. or AMD)

- Microsoft (Apple)

- Progressive (Safeco)

- Southwest Airlines (Pacific Southwest Airlines or PSA)

- Stryker (United States Surgical Corporation or USSC)

The research, which covered companies from their founding up until 2002, debunks a lot of entrenched myths when it comes to successful organizations and leaders.

Myth: Successful Leaders Are Big, Bold, Visionary Risk Takers

“10Xer”s (pronounced “ten-EX-ers”) are people who built companies that beat the industry index by at least 10 times. The research suggests that, instead of being big, bold, visionary risk-takers, 10Xers rely more on three core behaviors:

Behavior #1. Fanatic discipline—rather than strict adherence to rules and obedience to authority, the 10Xers’ brand of discipline is more about sticking consistently to their values, long-term goals, standards, and methods, no matter what.

One of the ways they exercise fanatic discipline is by going on the 20 Mile March. To 20 Mile March means to hit specified targets year after year with a long-term view in mind. The name comes from the concept of reaching a destination by hitting 20 miles a day, no more, no less, no matter what. The authors cite two South Pole expeditions in 1911 as an example: Team 1, led by Roald Amundsen, traveled no more than 20 miles a day, even when conditions were good. With their consistent pace, they finished the expedition right on schedule. Team 2, led by Robert Falcon Scott, pushed themselves to the brink of exhaustion on some days while sitting out all the gale-force winds they encountered. Team 2 reached the Pole 34 days later than Team 1 and died on their return journey.

A good 20 Mile March:

- Specifies both upper and lower bounds. The minimum target (lower bound) should be realistic enough to be achieved even during hard times, while the maximum (upper bound) keeps you from overextending yourself and becoming too weak in the face of challenges. Example: Amundsen’s team targeted 15 to 20 miles a day, even on days when they could do 25.

- Is customized to the enterprise. Performance makers should make sense for your company and your industry. These markers can be non-financial. Examples: For a church, it can be congregation size; for a school, it can be the students’ academic performance.

- Is achievable through your own actions, not reliant on outside factors. Don’t sit around waiting for conditions to change in your favor. Take action, and control what you can control.

- Falls within a reasonable time frame. A too-short 20 Mile March exposes you to greater risk, while a too-long one won’t make enough of an impact.

- Is consistent. 10X companies rarely missed their target. When they did, they quickly self-corrected.

Behavior #2. Empirical creativity—10Xers aren’t more daring than their comparison leaders, but they act decisively based on extensive observation and experimentation.

- Example: Amundsen read through notes and journals from previous expeditions to help him decide on a stable base camp location—a place no one else had considered before.

Behavior #3. Productive paranoia—10Xers consider every kind of nightmare scenario so that they can remain vigilant and prepare for the worst.

- Example: Amundsen thought of disastrous scenarios and left nothing to chance. He stored three tons of supplies for his team and clearly marked the way to supply depots in case they went off course.

All three core behaviors are driven by Level 5 ambition, which is an incredible ambition and strength of will geared towards the organization. 10Xers aren’t on the quest for personal greatness; instead, they want to build a great company, make a difference in the world, and leave a legacy behind.

Myth: Successful Companies Are Innovators

The research revealed that some 10X companies didn’t innovate as much as their competitors. They did, however, innovate just enough and approached innovation in a way that increased their chances for success: They fired bullets before cannonballs. Firing “bullets” means testing and experimenting to see what they hit. Then, once they’d gathered convincing data, they concentrated their firepower into “cannonballs” calibrated for success, aiming in the direction that bullets had shown to have the greatest potential. They never launched uncalibrated cannonballs.

A bullet can come in the form of a new product, service, technology, process, or acquisition, as long as it doesn’t cost much, has minimal consequences, and doesn’t disrupt the enterprise.

- Example: When Amgen wanted to find the best application for recombinant-DNA technology, they first fired bullets by experimenting with a dozen different uses of the tech, from a vaccine to a chicken growth hormone. Among the bullets they fired, Amgen found erythropoietin (EPO) to show the most promise. Once Amgen gathered enough data, they fired a cannonball and rolled out EPO. It went on to become the first billion-dollar bioengineered product in history.

Myth: Successful Leaders Have to Move Fast, All the Time

Instead of focusing on speed, 10X leaders focus more on timing. They don’t respond to threats right away; they respond to threats the right way. They constantly ask, “What if?” and mitigate nightmare scenarios by:

1. Setting up buffers—10X cases had huge cash reserves to see them through the inevitable disruptive event.

2. Limiting and managing risk—they took fewer risks than the comparison companies. When it came to time-based risks, they didn’t panic and instead assessed the situation and made decisive moves based on the time they had.

3. Taking a macro and micro view of the landscape—they didn’t just pay attention to the work at hand but also kept an eye on their surroundings for oncoming threats. They addressed perceived threats accordingly.

- Example: In 1979, Intel faced a growing threat. Motorola was racking up design win after design win and, if they continued on this path, would become the industry standard, rendering Intel obsolete. Intel quickly formed a special team to analyze what Motorola was doing right and what Intel was doing wrong, then came up with a comprehensive plan called Operation CRUSH. Within the week, they started executing the plan. Intel then racked up 2,000 design wins in a year, crushing the Motorola threat.

Myth: Successful Companies Change Drastically to Keep Up With the Times

Based on the data, 10X companies changed less than their comparisons, recognizing that the only thing they had control over was themselves. They used this control to stay steadfast amid the chaos around them, employing fanatic discipline, empirical creativity, and productive paranoia, all while sticking to their SMaC (Specific, Methodical, and Consistent) recipe.

A SMaC recipe is a set of operating practices that strikes the balance between being durable and specific. It clearly and concisely outlines what a company should and shouldn’t do. Much like the United States Constitution, it has an enduring framework that is specific enough not to be ambiguous, while being flexible enough to allow for amendments when the need arises.

But with 10X cases, amendments were few and far between. They only changed their recipes 10 to 20 percent of the time over more than 20 years on average, exercising empirical creativity and productive paranoia when they did. They had the discipline to change only what needed to be changed, keeping the rest of the recipe intact.

Meanwhile, comparison companies changed their recipes 55 to 70 percent of the time over the same period. This suggests that changing too much too fast doesn’t give a company a chance to build momentum, rendering it unable to achieve sustained success.

Before changing a SMaC recipe, it pays to determine if it’s not working because you’re not consistent enough to stick to it or because circumstances truly warrant a change.

- Example: Faced with airline deregulation that would increase competition, Southwest Airlines’ then-CEO Howard Putnam determined that Southwest would not be greatly affected and that their best course of action was to keep doing what they were doing. He then created a SMaC recipe for Southwest that contained the practices that worked for them. It clearly outlined what they were supposed to do—“Use 737s as primary aircraft” (which would only entail one set of parts, manuals, and procedures)—and not do, such as “Don’t offer food” and “Don’t carry air freight or mail” (services that would bog down airplane turnaround time). Southwest’s simple and concise SMaC recipe based on empirical data saw the company through numerous disruptions in the airline industry and remained 80 percent intact through 25 years.

Myth: Successful Companies Are Just Luckier Than Others

Some people see luck as the only explanation for tremendous success; others see luck as a non-factor. The research found that neither extreme holds true. 10X companies and their comparisons had a fairly even playing field when it came to luck, having a comparable number of good-luck and bad-luck events.

What set 10X cases apart wasn’t the amount of luck they had, but what they did with what they were dealt. They showed that luck wasn’t a crucial factor for success, but return on luck was.

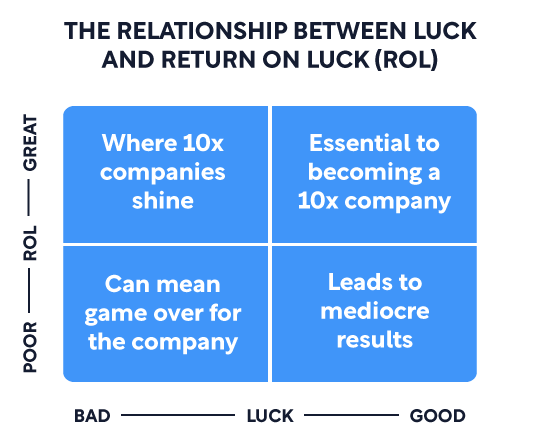

There are four possible scenarios when it comes to luck and return on luck:

1. Great return on good luck—10X companies didn’t coast on good luck and instead used good-luck events to their advantage. One of the most important types of good luck for an enterprise is finding the right people for your enterprise.

- Example: A Taiwanese scientist named Fu-Kuen Lin responded to Amgen’s job posting in the classifieds. Lin turned out to be an incredibly hard worker, obsessively working on the EPO gene for years. His hard work paid off, leading to the first billion-dollar bioengineered product. Amgen’s good luck in finding Lin led to massive success for the company.

2. Poor return on good luck—comparison companies had their fair share of good luck but failed to execute and make the most of it.

- Example: Intel’s comparison company, AMD, had a string of good luck: They won a court case, developed a great product, and had the market’s support. They had more good luck when Intel ran into some problems with defective chips. AMD was in the perfect position to overtake Intel, but they stumbled and were delayed for months. Then, they experienced another stroke of good luck when they acquired NexGen, a company with tech to rival Intel’s. Again, AMD failed to deliver, lagging behind in production. AMD’s series of good-luck events were all overturned by poor execution.

3. Great return on bad luck—10X companies used bad-luck events to display their full might. They exhibited resilience by using their bad luck to produce great outcomes.

- Example: In 1988, California voters passed Proposition 103, which lowered auto-insurance prices by 20 percent. It was consumers’ punitive response to car-insurance companies that made it difficult for customers to make claims after auto accidents. Progressive Insurance would have been greatly affected by this proposition, as 25 percent of their market was in California, but instead of panicking, they heard the consumers’ message loud and clear. Progressive responded by greatly improving their claims service. As a result, they made their way up from #13 in the market to #4 by the end of the era of analysis.

4. Poor return on bad luck—perhaps the only true form of luck. While one big good-luck event can’t lead to sustained greatness, a single bad-luck event or a series of events can kill a company. This is why it’s important to behave like a 10Xer and create buffers for bad-luck events.

- Example: Both Southwest and PSA faced a number of bad-luck events: oil shock, labor strikes, a recession. Southwest was prepared to weather the long season of bad luck. On the other hand, PSA kept making self-destructive moves like raising prices and increasing debt. Their poor return on bad luck meant that they were perpetually behind Southwest.

Behaving like a 10Xer who exercises fanatic discipline, empirical creativity, and productive paranoia can give you the best outcome, no matter what kind of luck you have. With good luck, these core behaviors can propel you to greatness; with bad luck, these core behaviors can help you survive or even push you to thrive. Luck isn’t the master of your fate—you are, and you can make the decision to become something great.

Chapter 1: Introduction

In business, as in life, the only thing certain is uncertainty. How, then, can companies survive—even thrive—when the future is unpredictable? Great by Choice, written by bestselling author Jim Collins and management professor Morten T. Hansen, gives some insight into that question through nine years of research, which started in 2002. Around that time, there were many extreme events that rocked the business landscape: The bull market crashed, the government’s financial position deteriorated, the terrorist attacks of 9/11 happened. And yet, some companies successfully navigated through the chaos.

Seeking to understand how some can weather great adversity better than others, the authors analyzed the performance of thousands of organizations during extreme situations. From an initial list of 20,400 companies, Collins and Hansen identified seven case studies that they dubbed “10X” companies—those that performed better than the industry average by at least 10 times during periods of upheaval. To get a clearer idea of what these high-performing companies did differently, the authors also identified a comparison company for each 10X company. These comparison companies didn’t perform quite as well, despite being in the same industry, in the same era, with similar opportunities as the 10X companies.

(Shortform note: Collins employs a similar method of comparative historical analysis in a previous book. Read our summary of Good to Great.)

Narrowing Down the 10X Companies

To be considered a 10X case, an enterprise had to meet three basic criteria:

- It must have demonstrated consistently impressive results in both its industry and in the stock market over 15+ years.

- It must have achieved these results during tumultuous times marked by unforeseen events.

- It must have been a young organization and/or started small before its spectacular rise.

Given these parameters, the authors narrowed down the 10X cases—and their comparison companies (in parentheses)—to the following:

- Amgen (comparison company: Genentech)

- Biomet (Kirschner)

- Intel (Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. or AMD)

- Microsoft (Apple)

- Progressive (Safeco)

- Southwest Airlines (Pacific Southwest Airlines or PSA)

- Stryker (United States Surgical Corporation or USSC)

(Shortform note: To learn more about the authors’ research methodologies, refer to the appendix section "Research Foundations" in Great by Choice.)

While the findings common among the 10X companies are no guarantee that an enterprise will be able to weather any storm, following their principles will likely give you a better chance of success than if you followed the comparisons’.

Note that the research tracked only up until 2002, so it’s entirely possible that the 10X companies no longer boast the same performance they once did. (On the flip side, comparison companies might have also made the jump from good to great, as in the case of Apple under Steve Jobs.) The authors examined these companies during their dynastic eras, or the 15+ years largely before the 2000s, so the research gives a snapshot of a period of stellar performance. Think of it as looking at a sports team’s dynasty—analyzing a company’s sustained performance over an era can still give useful insights, even if that era has already passed.

Debunking Myths

The research, which consisted of 7,000 historical documents that painted a picture of a company’s evolution from founding to 2002, dispels a lot of myths when it comes to successful organizations and leaders. Succeeding chapters will discuss all of these myths:

- Myth 1: Successful leaders are big, bold, visionary risk-takers. The evidence suggests that successful leaders rely more on empirical data than vision, and more on discipline and obsessive preparation than big risks.

- Myth 2: Successful companies are innovators. Some 10X companies didn’t innovate as much as their comparisons. They did, however, approach innovation in a way that increased their chances for success, combining it with creativity and discipline and having the ability to scale it.

- Myth 3: Successful leaders have to move fast, all the time. Instead of focusing on speed, 10X leaders focus more on timing.

- Myth 4: Successful companies keep up with a drastically changing environment by making their own drastic changes. The evidence shows that 10X companies changed less than their counterparts, even when the world around them was changing wildly.

- Myth 5: Successful companies are just luckier than others. The companies had a fairly even number of lucky breaks and misfortunes. The difference: 10X companies knew how to deal with the hand they were dealt.

Chapter 2: What Makes a 10Xer?

“10Xers” (pronounced “ten-EX-ers”) are people who built companies that beat the industry index by at least 10 times. They’re not all cut from the same cloth: They come from different backgrounds—with some growing up privileged, others poor—and have different personalities—some are flamboyant, others reserved. Dispelling an entrenched myth, the research suggests that they’re not more creative, more ambitious, or more visionary than their comparison leaders. What sets them apart? These three core behaviors that they have in common:

- Fanatic discipline

- Empirical creativity

- Productive paranoia

Fanatic Discipline

While people normally associate discipline with compliance with rules and obedience to authority, the 10Xers’ brand of discipline is more about sticking to their guns, no matter what. They adhere consistently to their values, long-term goals, standards, and methods, even if it means being nonconformist and going against what society expects.

- Example: In the late 1990s, Peter Lewis, CEO of Progressive Insurance, faced a dilemma. Progressive was experiencing wild fluctuations in its stock because Lewis refused to let analysts in on the company’s expected earnings—a widespread practice that enabled analysts to “predict” and “manage” earnings every quarter, thereby keeping markets steady. Lewis thought the practice was a dishonest and lazy shortcut that circumvented deep analysis and research. Giving into it would go against his principles, but not giving into it would leave his company vulnerable. He thus decided to do something no other SEC-listed company had done before: Progressive would publish monthly financial statements so that analysts could more accurately predict the company’s earnings using real data. Lewis refused to accept what seemed like the only options and found a way to keep Progressive secure without compromising his values.

Empirical Creativity

People tend to think that leaders of successful companies make especially bold moves, yet the research revealed that 10Xers generally weren’t more daring than their comparison leaders. The difference lies in the process leading to those bold moves.

While most leaders rely on conventional wisdom, expert opinions, or even untested ideas, 10Xers rely on their own creative instincts backed by empirical data. Their decisive actions are evidence-based, coming only after extensive observation and experimentation. This allows them to make bold, creative moves while also managing their risks.

- Example: After a routine checkup, Intel chief executive Andy Grove learned that he might have prostate cancer. He didn’t leave his treatment plan up to the doctors and instead spent all his free time on research. He read everything he could find that was related to the subject, dove deep into all the studies, and found that there were conflicting opinions in the medical world regarding treatment. After considering all the data, he decided on his own treatment plan. Because the medical world itself hadn’t come to a consensus regarding the best course of action, Grove had to learn everything he could about it before coming to his own evidence-based decision.

Productive Paranoia

10Xers have one constant thought: “What if?” They consider every kind of nightmare scenario so that they can remain vigilant and prepare for the worst. Even when the skies are clear and conditions are perfect, they are always preparing for a storm.

- Example: Bill Gates has always been guided by fear, whether Microsoft was just starting out or already a solid player in the industry. In the beginning, he wanted to make sure that Microsoft had enough cash to last an entire year without revenue. This kind of worst-case-scenario thinking would continue as Microsoft grew; in 1991, his “nightmare memo” was leaked to the press, listing all sorts of threats, even though the company was fast becoming a major player. Such memos were his way of outlining potential threats so that he could prepare for them. A year after the memo was leaked, Gates said, “If I really believed this stuff about our invincibility, I suppose I would take more vacations.” In contrast, his counterpart over at Apple, John Sculley, went on a nine-week sabbatical after Apple had one really good year. While Sculley may have also had a great work ethic, Gates was always on, always thinking about keeping the company secure, no matter how many good years Microsoft had.

Level 5 Ambition

10Xers are unyielding and ultra-disciplined, obsessive about evidence, and incredibly paranoid. It all seems like a lot to handle and yet 10Xers constantly attract talented people who want to work with them. That’s because 10Xers aren’t on a quest for personal greatness. Their core behaviors are driven by something greater than themselves, a relentless passion with a purpose: the ambition to build a great company, make a difference in the world, and leave a legacy behind.

- Example: Peter Lewis of Progressive Insurance had one goal: to make Progressive great. He accomplished this and did it so well that the company continued to prosper even after he handed over the reins to his successor.

(Shortform note: To learn more about Level 5 Ambition, read our summary of The 5 Levels of Leadership.)

The succeeding chapters explore how Level 5 ambition together with 10Xer core behaviors—fanatic discipline, empirical creativity, productive paranoia—all come into play when building a 10X company.

Example of a 10Xer vs. a Non-10Xer

In 1911, two teams set out on a historic journey to reach the South Pole. The first team, led by Roald Amundsen, would successfully reach the Pole and make it back to their home base according to schedule. The second, led by Robert Falcon Scott, reached the Pole 34 days later and would die on the return journey. Both teams started their trips within days of each other, facing the same distance and the same brutal temperatures and winds. The difference? Amundsen’s 10X mindset:

- He was disciplined. He anticipated the endurance needed in an unforgiving environment and so trained long and hard, at some point biking 2,000 miles. He even apprenticed with Eskimos to learn what worked in polar conditions (dogs instead of ponies to pull sleds, for example).

- He used empirical data creatively. Amundsen read through notes and journals from previous expeditions to help him decide on a stable base camp location—a place no one else had considered before.

- He was productively paranoid. He thought of disastrous scenarios and left nothing to chance. He stored three tons of supplies for his team and clearly marked the way to supply depots in case they went off course.

Meanwhile, Scott didn’t go through rigorous training, used untested motor sledges that failed in the extreme polar conditions, and brought the bare minimum of supplies. In the end, he and his team tragically paid the price.

Exercise: Behave Like a 10Xer

Prepare your company for challenging times by adopting 10Xers’ core behaviors.

10Xers are hyper-disciplined, adhering to their values no matter what. But you can’t be consistent with your values if you don’t know what they are. Reflect on your values: What’s important to you? What are your most important goals?

Come up with your own “nightmare memo” by listing down the threats to your company. What do you need to do to safeguard your company against these threats?

Chapter 3: How 10Xers Hit Targets

Comparison companies were relentless in their pursuit of growth in good times, which left them vulnerable in bad times. In contrast, 10Xers went on the 20 Mile March—they opted for consistent performance, in good times and bad. This chapter spotlights how this fanatic discipline served the 10X cases.

To 20 Mile March means to hit specified targets year after year with a long-term view in mind. The name comes from the concept of reaching a destination by hitting 20 miles a day, no more, no less—no matter what. For example, if you were to walk 3,000 miles from California to Maine, you would walk 20 miles daily, whether it was sunny or stormy, whether you were in excellent form or feeling spent. Your steady pace would ensure that you had enough reserves to keep going, day after day, no matter what the conditions. If another traveler were to walk the same distance with a different tactic, pushing himself to go 40 miles on days when the weather was great, he would be too exhausted to keep going by the time the harsh winter arrives. He would end up sitting out the whole winter before recommencing in the spring, already having lost a lot of ground. By the time you reach Maine, he would’ve only gone halfway.

- Example: During the South Pole expedition, Amundsen never deviated from his target range of 15 to 20 miles a day, even on good days when the team could have gone 25 miles. He finished the expedition averaging 15.5 miles a day. On the other hand, Scott would push his team extra hard on good days, then sit it out when faced with gale-force winds. He did not survive the expedition.

Formula for a Good 20 Mile March

The 20 Mile March shows that slow and steady indeed wins the race. A good 20 Mile March is characterized by the following:

1. It specifies both lower and upper bounds. 10X companies did everything they could to meet targets year after year—no excuses—and these targets had both a minimum and a maximum. The minimum target, or the lower bound, was realistic enough so that a company could achieve it even during hard times, albeit with tremendous effort. The maximum, or the upper bound, was the farthest a company allowed itself to go, even when conditions were favorable.

Having upper bounds requires immense self-control. You have to hold back even when you can push a little harder, even when competitors are growing faster, even when Wall Street is putting on the pressure. This keeps you from overextending yourself or becoming too weak to face unexpected challenges. It’s just like Amundsen sticking to his 15-to-20-mile range.

- Example: Under CEO John Brown, Stryker’s target was a 20 percent net income growth every year. For 16 out of 19 years, Stryker hit this consistently and didn’t go above 30 percent. With this steady pace, a dollar invested in Stryker in 1979 was worth 350 times more by 2002. Meanwhile, Stryker’s comparison company USSC aggressively pursued growth, banking on and investing heavily in new technology. It grew 248 percent in three years, but this explosiveness was short-lived. The company was beset with issues like healthcare reform and strong competitors, and revenues fell. Things got so dire that by 1998, USSC was acquired by Tyco.

2. It’s consistent. Research shows that 10X companies didn’t meet their target 100 percent of the time. But on the rare occasion when they did miss the mark, they immediately did what needed to be done to get back on course.

3. It’s customized to the enterprise. The 20 Mile March isn’t one-size-fits-all. While a 20 percent lower bound for net income may make sense for a company like Stryker, it might not apply to your company. Don’t rely on outside factors to dictate your metrics and instead come up with performance markers that make sense for your organization. They might even be non-financial—for a church, it could be congregation size; for a school, it might be student performance.

4. It’s achievable through your own actions, not reliant on outside factors. 10Xers don’t sit around waiting for conditions to change in their favor. They know that there are many things they can’t control, like government regulations, technological advancements, and global competition, so they take action by controlling what they can control.

- Example: Alice Byrne Elementary School in Yuma, Arizona was well below state averages when it came to third-grade reading. They had limited resources, which they had no control over, and so they trained their attention on the things that they did have control over. By sticking to a stringent program involving close instruction, assessment, and intervention, the school was eventually able to raise its reading performance to 20 points above state averages.

5. It falls within a reasonable time frame. A too-short 20 Mile March exposes you to greater risk, while a too-long one won’t make enough of an impact.

Why the 20 Mile March Works

There are three reasons 20 Mile Marching leads to success:

- It makes you more confident. Forget motivational emails and pep rallies—there’s nothing quite like a win in the face of challenging circumstances to boost your confidence. When you see what your enterprise can accomplish despite conditions outside of your control, you take responsibility for your own success.

- It girds you for disruptive events. Comparison companies that pushed for maximum growth when times were good ended up depleting their resources, resulting in big setbacks when they ran into turbulence. In contrast, all 10X winners saw turbulence as their time to shine—they always outperformed comparison companies during difficult times.

- It keeps you in control. Natural disasters, financial markets, regulation changes—so many things are out of your control. But the 20 Mile March gives you a clear direction and purpose. It provides you with a beacon of light when everything around you is a swirl of chaos and uncertainty.

Example of a 20 Mile Marcher

Southwest Airlines’ 20 Mile March kept them stable even through the industry downturn in the 1990s and after 9/11 by:

- Specifying lower bounds and upper bounds, and remaining consistent. They pushed themselves to be profitable year after year, but they also put a cap on growth: In 1996, despite hundreds of cities seeking to enlist Southwest’s services, the company only expanded to four cities. They didn’t sacrifice long-term success for short-term growth.

- Having no excuses. The airline industry faced so many issues, from deregulation to strikes to fuel crises. While other airlines furloughed thousands of people and filed for bankruptcy, Southwest soldiered on and remained profitable for an impressive 30 years.

Exercise: Determine Your 20 Mile March

Build an enterprise that lasts by beginning your 20 Mile March.

What is your goal for the next 15 to 30 years?

How can you break down this goal into a 20 Mile March? What is a consistent target that you will aim to hit year after year?

Chapter 4: How 10Xers Innovate

While the 20 Mile March is reliable, bringing order to a chaotic world, it seems to leave little room for innovation. This chapter explores how to balance the need for unbending consistency with the need to adapt to a changing world using empirical creativity.

One of the surprising findings of the research was that the most innovative companies weren’t necessarily the most successful. In fact, only three out of the seven 10X companies could be considered more innovative than their comparison companies. This is not to say that 10X companies didn’t innovate; they did, but they innovated just enough and they did so methodically.

But what is “enough” when it comes to innovation? That varies from industry to industry:

- High innovation threshold: semiconductors, biotechnology, computers, software—companies need to constantly introduce new devices, products, and features or risk becoming obsolete.

- Medium innovation threshold: medical devices—technological advancement isn’t as fast-paced as it is in the high-threshold category.

- Low innovation threshold: airlines, insurance—airline ticketing, flying, and other services don’t need to be updated every few months.

No matter the threshold, the 10Xers are systematic when it comes to innovation. They don’t have a crystal ball or an uncanny ability to see what will work, so they innovate with creativity and discipline.

Innovation in Small Doses

When deciding on new products or services to introduce, the research shows that 10X companies took a “bullets before cannonballs” approach, relying on empirical data to back up innovation. They first fired off “bullets,” testing and experimenting to see what they hit. Once they’d gathered convincing data, they brought out the big guns. They concentrated all their firepower into “cannonballs” that were calibrated for success, aimed in the direction that bullets had shown to have the greatest potential.

In contrast, comparison companies fired uncalibrated cannonballs straightaway. These big bets, lacking empirical data to back them up, depleted resources and left the comparison companies vulnerable in times of trouble.

- Example: In 1968, Southwest’s comparison company, PSA, went all out when they aimed to be a one-stop-shop for travelers, launching a program called “Fly-Drive-Sleep.” Instead of testing the concept by buying just one hotel and partnering with a rental-car company (firing bullets), they took out long-term leases on hotels and bought a rental-car company, expanding fast (firing an uncalibrated cannonball). The cannonball missed its mark and PSA suffered losses year after year. After that, PSA fired uncalibrated cannonball after uncalibrated cannonball, hoping one would hit the mark: They acquired jumbo jets, they tried launching a joint venture, they went into oil and gas exploration. However, they were also plagued with issue after issue, from an oil embargo to a recession to lawsuits and workers’ strikes. It all proved to be too much and by 1986, they were taken over by US Air.

It’s never a good idea to fire an uncalibrated cannonball, whether it hits the mark or not. If it fails, then it may leave you vulnerable to an ever-changing world. If it succeeds, then it may encourage you to keep recklessly firing uncalibrated cannonballs. Neither is it a good idea to simply fire bullets without following through with a calibrated cannonball—your company won’t do anything great that way. Do what 10Xers do and fire bullets first to see what works, then fire a cannonball. Forget about any bullets that weren’t shown to hit anything worthwhile. Better to have a field of misfired bullets than an uncalibrated cannonball that can cause irreparable damage.

It’s worth noting that comparison companies weren’t the only ones to launch uncalibrated cannonballs—even 10X companies made mistakes. The difference was that comparison companies tended to try to salvage the situation by firing another cannonball, while 10X companies quickly learned their lesson and went back to firing bullets.

Characteristics of a Good Bullet

A bullet can be a new product, service, technology, process, or even an acquisition, as long as it has these three characteristics:

- It doesn’t cost much. Take note that low cost is relative to the enterprise. What doesn’t cost much for a billion-dollar company will likely be too much for a startup.

- It has minimal consequences. A good bullet doesn’t expose a company to much risk—if it doesn’t work, the company won’t suffer.

- It doesn’t disrupt the enterprise. The bullet might entail a lot of work from a person or a group of people, but it shouldn’t distract the whole company.

- Example: Whenever Biomet made a new acquisition, they made sure that their balance sheet would remain strong. These acquisitions, or bullets, thus met the three criteria. Meanwhile, their comparison company, Kirschner, made big, risky acquisitions that left them heavily in debt. Kirschner eventually sold out to Biomet.

Sometimes, you don’t even have to fire your own bullets—you can learn from what others have done.

- Example: Southwest Airlines was a self-proclaimed copycat of PSA. They replicated in Texas what PSA did in California, mimicking everything from the operation manual to the culture. But Southwest came out on top by sticking to their 20 Mile March and continuously firing bullets before cannonballs.

Example of a 10X Company That Innovated the Right Way

Amgen wanted to find the best application of recombinant-DNA technology, so they:

- Fired bullets… They tried a dozen different applications for recombinant-DNA technology, from a Hepatitis-B vaccine to a chicken growth hormone to a bioengineered dye for blue jeans.

- ...then fired a calibrated cannonball. Among the bullets, erythropoietin (or EPO, which stimulates the production of red blood cells) was the most viable. Once Amgen was satisfied with the empirical data, they fired a cannonball: They funneled resources into rolling out EPO.

Amgen scored a huge win with EPO, as it went on to become the first billion-dollar bioengineered product in history.

Exercise: Innovate Like a 10Xer

10Xers increase their chances for success by using empirical data to back innovation.

Think about cannonballs that you’ve fired. Which ones were calibrated, and which ones were uncalibrated?

What were the results of firing calibrated cannonballs?

What were the results of firing uncalibrated cannonballs?

Reflect on your uncalibrated cannonballs. What kind of bullets could you have fired to determine if you were on the right track?

Chapter 5: How 10Xers Prepare for the Unexpected

The 20 Mile March (fanatic discipline) and firing bullets before cannonballs (empirical creativity) might be enough to achieve success when conditions are stable. But the world is plagued by instability; you never know what’s going to happen next, so you need more than just discipline and creativity. This is where productive paranoia comes in.

When disaster strikes, there are only three outcomes for an enterprise: They pull ahead, they lag behind, or they hit what the authors call the “Death Line” (game over for the enterprise). 10X companies pulled ahead by going by a credo: If you stay ready, you don’t have to get ready. They knew that calamities were impossible to predict but that they could and would happen, so it was best to be prepared for every eventuality. Driven by productive paranoia, they constantly asked “What if?” and found ways to mitigate nightmare scenarios.

Putting Productive Paranoia into Practice

10X companies used productive paranoia to:

1. Set up buffers. An unforeseen event can drain an enterprise’s resources, crippling or killing the company. The 10X cases protected themselves by building cash reserves, having three to 10 times the ratio of cash to assets compared to other companies. In a perfect world, having so much idle cash may not be a good use of a company’s resources—but the reality is, it’s not a perfect world. Disruptive events are inevitable, and cash on hand can serve as a shock absorber, increasing a company’s chances of survival.

- Example: When the terrorist attacks of 9/11 happened, Southwest was uniquely positioned. Not only did they have crisis and contingency plans in place, but they also had plenty of cash on hand—$1 billion to be exact! While competitors cut back on operations right after 9/11, it was business as usual for Southwest. They operated all their regular flights, retained all their employees, and remained profitable through 2001. They were the only major airline to make a profit in 2002.

2. Limit and manage risk. 10X companies took risks, but they took fewer risks than the comparison companies. They avoided risks that could cripple or kill them (send them to the Death Line), risks that didn’t come with a big enough payoff, and risks that would make them vulnerable to events they couldn’t control. When a time-based risk came into play, the 10X companies didn’t make panicked decisions. Instead, they assessed the situation and made decisive moves based on the time frame. They took their time when they could but moved fast when they had to.

- Example: In 1989, Stryker noted in their annual report that rising healthcare costs in the US could, paradoxically, lead to lower prices on medical products, which would be bad for their business. Stryker, a properly paranoid 10X company, prepared for this what-if scenario by squirreling away cash through the 1990s. By the late 1990s, rising healthcare costs led to the emergence of hospital buying groups on an acquisition spree. Companies either had to scale up or be shut out. With their cash reserves from years of preparation, Stryker was perfectly poised to acquire Howmedica. After the purchase, Stryker became one of the biggest players in the industry.

3. Take both a macro and micro view of the landscape. As 10Xers go on their 20 Mile March, they don’t just look at the road right in front of them, tracking every step. They also look around them to see if there are any threats. When they sense danger, they take a step back and survey the landscape (“zoom out”). They assess how much time they have before the threat is within striking distance, then they adjust their plans and focus on the details of mitigating the threat, aiming for flawless execution (“zoom in”).

- Example: In 1979, Motorola posed a big problem for Intel. Motorola was racking up design win after design win and, if they continued on this path, they would become the industry standard, rendering Intel obsolete. Recognizing the urgency, Intel quickly formed a special team to address the looming threat. Within three days, the team had looked at the big picture—analyzing what Motorola was doing right and what Intel was doing wrong, and deciding on the best course of action—before turning their attention to the details. They formulated a comprehensive plan called Operation CRUSH and, within the week, enlisted a hundred team members to execute the plan. Intel proceeded to rack up 2,000 design wins in a year, crushing the Motorola threat.

Example of Productive Paranoia

In 1996, David Breashears and his film crew were at Camp III on Mt. Everest, preparing to climb to the summit. As they got ready for their ascent, Breashears spotted dozens of climbers, led by guides Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, making their way up from Camp II. Breashears assessed the situation and went through his list of nightmare scenarios: anchors dislodging, an unexpected storm, less experienced climbers getting in the way, and so on. He concluded that an overcrowded summit posed too many risks, and he thus decided to abandon their summit bid for the time being. It was a luxury his team could afford, given his productive paranoia:

- He had built buffers by stocking up on enough oxygen canisters to fuel more than one summit bid and enough supplies to last them three more weeks.

- He limited risk, assessing how their risk profile changed with the addition of dozens of other climbers. He decided to avoid a situation that could put them in peril.

- He looked at the big picture then adjusted his plans accordingly. Given that the presence of other climbers increased their risk and that his team had the capacity to make another bid, he made the decision to make their way down and try another day.

In contrast, Hall and Fischer only had enough oxygen for one summit bid, so they had no choice but to keep going. They ended up getting caught in an unexpected storm and dying on Everest. Breashears and his team had enough oxygen canisters to help the rescue team in their efforts, plus enough left over for their own ascent. They successfully reached the summit a couple of weeks later.

Exercise: Prepare Like a 10Xer

There’s no telling what kind of unfortunate event is going to happen, but given an unstable, constantly changing world, disruptions are inevitable. Shield yourself against these threats by putting paranoia to good use.

Go back to your nightmare memo. How much time do you have to respond to each of the threats on your list?

Take a look at the most immediate threat. Generate your own Operation CRUSH, a detailed action plan outlining the best response to the threat given the time frame.

Chapter 6: How 10Xers Stay the Course

When so many things are rapidly changing, your first instinct might be to also rapidly change to keep up with the times. But 10X companies recognized that the only thing that they had control over was themselves, and they used this control to stay steadfast amid the chaos surrounding them. They employed fanatic discipline, empirical creativity, and productive paranoia, and they stuck to their SMaC recipe throughout any disruption.

What Is SMaC?

SMaC stands for Specific, Methodical, and Consistent. You can use it as a noun (as in “SMaC prepares a company for bad times”), an adjective (“We need some SMaC procedures”), or a verb (“Can you SMaC the new directives?”). A SMaC recipe is a set of operating practices that strikes the balance between being:

- Durable—it remains largely unchanged through decades and can apply to a wide range of situations; and

- Specific—it clearly outlines what a company should and should not do. All of the 10X companies had “don’t do” points in their SMaC recipes.

- Example: Don’t wait for perfection to launch a product; aim for good enough, then improve (Microsoft); don’t be the first but also don’t be the last when it comes to innovation (Stryker).

A SMaC recipe is something a company can turn to, especially in extreme circumstances, to remind them of what they need to do. It’s not something that changes frequently—much like the United States Constitution, it has an enduring framework that is specific enough not to be ambiguous or open to misinterpretation, while being flexible enough to allow for amendments when the need arises.

How and When 10Xers Change a SMaC Recipe

So many things are always changing in the world, from the economy to government regulations to the political situation to the environment...the list goes on. If your enterprise were to react to every change, you’d never find your footing. And yet, if you were never to react to any change, you might get left behind and become obsolete.

While 10X companies created SMaC recipes that served them well for a long time, they were still open to carefully considered change when necessary. They blocked out the noise, recognized signals to change, and had the wisdom to know the difference.

You shouldn’t take a change in the recipe lightly. The research findings show that the 10X cases only changed 10 to 20 percent of their recipes over more than 20 years on average. Meanwhile, comparison companies changed 55 to 70 percent of their recipes over the same period. While some might argue that comparison companies had to keep changing their SMaC recipes until they got it right, it’s more likely that getting it right the first time and being consistent is the key to success.

- Example: In the eras of analysis, Microsoft changed only 15% of their SMaC recipe, while Apple amended 60%. Apple kept changing both their leaders and their positioning, swinging wildly from mass-market computers to premium computers and back. They only found their footing after Steve Jobs’s return: They went back to Jobs’s original recipe and stuck with it, eventually achieving tremendous success.

When they did amend their SMaC recipe, 10Xers adhered to their core behaviors:

- Fanatic discipline—they were thoughtful and deliberate in their amendments, always changing only what needed to be changed and retaining the rest of the recipe.

- Empirical creativity—10X companies used the bullets-before-cannonballs approach by testing and gathering empirical evidence before incorporating something new into the recipe.

- Example: Memory chips were an integral part of Intel’s business, but they were fast becoming unviable due to the proliferation of cheaper Japanese products. Fortunately, Intel had fired other bullets and gradually built its microprocessor business over the years. They didn’t have to start from scratch when they let go of memory chips and switched over to microprocessors. (They also exhibited discipline by not changing anything else in their SMaC recipe—they continued investing in R&D, stayed true to their tagline of “Intel Delivers,” and so on, resulting in an impressive performance throughout the era of analysis.) In contrast, their comparison company AMD had a lot of good ideas, but it never stuck with any of them, pivoting from one recipe to the next. Thus, they were never able to gain momentum and never attained 10X success.

- Productive paranoia—10X companies kept an eye out for any changes in the environment, then adapted as needed.

- Example: In 1994, Bill Gates dedicated his “Think Week” to the Internet and organized a retreat so that Microsoft could assess the threat. After a couple of months, they concluded that the Internet was going to be a huge disruptor, and they thus acted quickly and decisively. Gates released an eight-page memo about the rising importance of the Internet, and Microsoft directed some of their energy towards developing Internet Explorer. It was a big change in their business, but Microsoft retained the rest of the SMaC recipe, never veering away from their core business, pricing strategy, and other SMaC ingredients.

If your enterprise isn’t growing as much as you think it should, it’s time to re-evaluate your SMaC recipe. Determine if it’s not working because you’re not sticking to it, or because circumstances truly require a change.

Example of an Effective SMaC Recipe

Faced with airline deregulation that would increase competition, Southwest Airlines’ then-CEO Howard Putnam evaluated how the disruption would affect their business. He concluded that, despite a change that would rock the industry, Southwest would not be greatly affected. Their best course of action was to simply keep doing what they were doing. He then formulated a SMaC recipe for Southwest that contained the practices that worked (and didn’t work) for them. It clearly outlined what they were supposed to do and not do, such as:

- DO: Use 737s as their primary aircraft—why? Because using one type of aircraft means one set of parts, training manuals, and procedures.

- DON’T: Offer food, or carry air freight or mail—why? Because adding these services would bog down airplane turnaround time.

Southwest’s SMaC recipe was simple, concise, easy to understand, and based on empirical data. It was so enduring and effective that, despite numerous disruptions in the airline industry (from fuel shocks to strikes to 9/11), the company only amended about 20 percent of the list in 25 years. These changes made room for Internet booking and longer flights, enabling Southwest to keep up with the times while still keeping the rest of their recipe intact.

In contrast, their comparison company, PSA, effectively abandoned their recipe—the very recipe Southwest mimicked—as crisis after crisis pummelled them. PSA tried to become more like United Airlines, changing 70 percent of their recipe along the way. They eventually sold out to US Air.

Exercise: Formulate Your Own SMaC Recipe

Increase your chances of surviving and thriving in a world of chronic instability. Create a formula that’s specific, methodical, and consistent.

Does your enterprise currently have a SMaC recipe? If yes, is there anything that you need to change?

If your enterprise doesn’t have a SMaC recipe, answer: Based on empirical evidence, what specific practices have led to success and why? What specific practices have led to failure and why?

Given your insights from the previous questions, write a SMaC recipe consisting of eight to 12 points. These points should work together as a system, should cover a broad range of issues and situations, and should be able to endure for at least a decade.

Chapter 7: How 10Xers Treat Luck

Just how lucky were the 10X companies in the study? Did they get more good luck and less bad luck than their comparisons? Could their good fortune (and their comparisons’ bad fortune) perhaps explain their massive success?

While “luck” seems like an intangible concept, the authors came up with a methodology to measure it and determine what kind of role it played in a company’s success.

Methodology and Findings

To quantify luck, the research team followed this methodology:

- They defined luck. A “luck event” is something that happened outside of a company’s actions, that could seriously impact the company in either a good or bad way, and that was somewhat unpredictable.

- They pinpointed luck events and analyzed their importance in the histories of both the 10X companies and comparison companies. Example: Finding the EPO gene and getting FDA approval was considered a good luck event of high importance for Amgen; a competitor finding their way around proprietary technology and getting their own patent for EPO was considered a bad luck event of high importance for Amgen.

- They determined if 10X cases had more good-luck events than their comparisons. Finding: On average, 10X cases had seven good-luck events versus comparison cases’ eight.

- They determined if comparison cases had more bad-luck events than 10X cases. Finding: On average, both 10X companies and their comparisons had about nine bad-luck events.

- They determined if there was one big-good luck event that catapulted 10X companies to success. Finding: No evidence to support this.

- They determined if 10X companies had a lot of good luck in the beginning, giving them momentum that propelled them far ahead of their competitors right from the start. Finding: No evidence to support this.

The research revealed that 10X companies and their comparisons had a fairly even playing field when it came to luck. What set them apart wasn’t the amount of luck that they had, but what they did with the hand they were dealt.

Making the Most of Luck

Some people see luck as the only explanation for massive success; others see luck as a non-factor. But the research found that neither extreme holds true. Some companies and some people are indeed luckier than others—people can be born into better circumstances with many more opportunities. However, luck can’t carry you all the way through to success. Whatever luck you get requires action on your part to determine the outcome.

- Example: Bill Gates can be considered incredibly lucky: He was born into a well-off family, had a private school education, grew up when personal computers were on the rise, and happened to see a magazine cover story that planted the idea for a product. However, many others had the same kind of luck when it came to their background, and not a lot of people achieved Gates’s level of success. Gates set himself apart by taking an idea and running with it—he dropped out of college, uprooted himself to another state, and worked round the clock to build a company.

Put simply, 10X companies did more with the luck that they got. Whether it was good luck or bad luck, they got a higher return on their luck.

There are four possible scenarios when it comes to luck and outcomes:

1. Great return on good luck. This is when a company (or a person, like Bill Gates) has a good-luck event and uses it to their advantage. 10X companies didn’t coast on these events and instead used them to fuel growth. One of the most important types of good luck is finding the right people for your enterprise.

- Example: A Taiwanese scientist named Fu-Kuen Lin responded to Amgen’s job posting in the classifieds. Lin turned out to be an incredibly hard worker, obsessively working on the EPO gene for years. His hard work paid off, leading to the first billion-dollar bioengineered product. Amgen’s good luck in finding Lin led to massive success for the company.

2. Poor return on good luck. In contrast with 10X companies, comparison companies had good luck but failed to execute and make the most of it.

- Example: Intel’s comparison company, AMD, had a string of good luck: They won a court case, developed a great product, and had the market’s support. They had more good luck when Intel ran into some problems with defective chips. AMD was in the perfect position to overtake Intel, but they stumbled and were delayed for months. Then, they experienced another stroke of good luck when they acquired NexGen, a company with tech to rival Intel’s. Again, AMD failed to deliver, lagging behind in production. AMD’s series of good-luck events were all overturned by poor execution.

3. Great return on bad luck. A bad-luck event is when a 10X company gets to display its full might. As the research shows, every company has its share of bad luck, but not every company makes it out alive. Great companies are resilient and know how to use this bad luck to produce great outcomes. Instead of giving up or just chalking it up to misfortune, they ask, “How can this event make us a better company?” Then they roll up their sleeves and get to work.

- Example: In 1988, California voters passed Proposition 103, which lowered auto-insurance prices by 20 percent. This was a huge blow to Progressive Insurance as 25 percent of their market was in California. Instead of panicking, CEO Peter Lewis quickly tried to figure out what was happening and learned that customers hated dealing with insurance companies due to the economic cost and hassle. Voting for the proposition was consumers’ punitive response to the difficulties car-insurance companies put them through. Lewis used this insight to greatly improve the company’s claims service. As a result, they gradually made their way up from #13 in the market to #4 by the end of the era of analysis.

4. Poor return on bad luck. This is perhaps the only true form of luck. While one big good-luck event can’t lead to sustained greatness, a single bad-luck event or series of events can kill a company. This is why it’s important to behave like a 10Xer—you need to prepare for bad-luck events because they are bound to happen. Your company needs to have the means to survive long enough until the next good-luck event.

- Example: Both Southwest and PSA faced a number of bad-luck events: oil shock, labor strikes, a recession. While Southwest was prepared to weather the long season of bad luck, PSA was not. PSA kept trying to manage their bad luck by making self-destructive moves like raising prices and increasing debt. Their poor return on bad luck meant that they were perpetually behind Southwest.

Behaving like a 10Xer who exercises fanatic discipline, empirical creativity, and productive paranoia can give you the best outcome, no matter what kind of luck you have. With good luck, these core behaviors can propel you to greatness; with bad luck, these behaviors can help you survive or even push you to thrive.

Life is uncertain and unpredictable. Whether something good or bad happens is out of your control, but what you do with what you get is entirely up to you. If you rely purely on luck, then your fate changes as you swing from a good-luck event to a bad one. If you rely on yourself—20 Mile Marching, firing bullets before cannonballs, managing risk, and sticking to your SMaC recipe—you can turn good or bad luck into something amazing. You are the master of your fate; you can make the decision to become something great.

Exercise: Make the Most of Your Luck

It’s not what happens to you that matters—it’s what you do with it that counts.

List all significant luck events that you’ve had in the past five years. Assess whether each one was a good-luck event or a bad-luck event, and if it was of medium or high importance.

How did you respond to each luck event and what were the outcomes?

What could you have done differently to get a higher return on luck?