1-Page Summary

Habits are a shortcut for your brain - you execute automatic behaviors without having to think hard about it. Habits develop when the behavior has solved the problem continuously in the past.

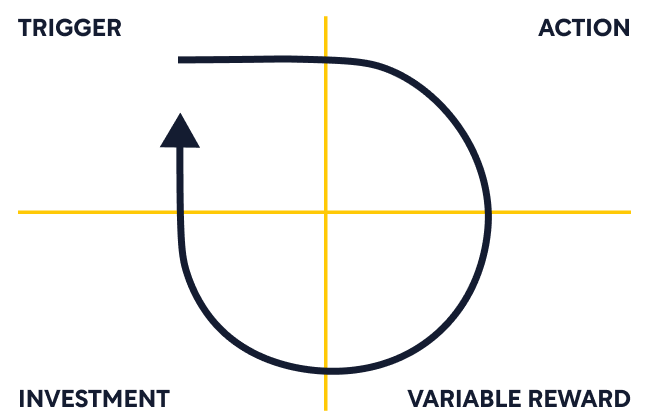

Habit-forming products use a 4-step loop to hook you:

- A trigger prompts the behavior.

- Triggers can be external or internal. External triggers come from outside a person’s thinking (e.g. phone notifications or seeing an advertisement). Internal triggers are internal drives (e.g. relieving boredom or loneliness).

- For products, behaviors often begin with external triggers. Then, as the habit forms, the behavior becomes associated with internal triggers.

- The trigger prompts an action, which is a behavior done in anticipation of a reward.

- An action is more likely when there is motivation to do it, and when it is easier to do.

- The action delivers a variable reward.

- Predictable rewards don’t cause cravings. You don’t crave turning on your faucet since you know what happens every time.

- In contrast, variable rewards prompt more intense dopamine hits and push the user to desire the next hit.

- In completing the action, the user invests in the product, improving her future experience and increasing the likelihood of completing another loop in the future.

- Investments include inviting friends, storing data, building a reputation, and learning to use features.

Each successive loop makes the next loop more likely to occur, causing a flywheel effect. To explain each in more detail:

Trigger

External triggers are delivered through the environment. They contain information on what the user should do next, like app notifications prompting users to return to see a photo.

Over time, as a product becomes associated with a thought, emotion, or preexisting routine, users return based on internal triggers. Emotions - especially negative ones like boredom, loneliness, confusion, lack of purpose, and indecisiveness - are powerful internal triggers. These triggers may be short and minor, possibly even subconscious.

To build a habit, you need to solve a user’s pain so that the user associates your product with relief.

To discover the root problem, ask “Why?” as many times as it takes to get to an emotion.

Action

To initiate action in a habit, doing must be easier than thinking. An action has three requirements:

- Sufficient motivation

- Sufficient ability

- A trigger to activate the behavior

Make the process to use your product as simple as possible. Lay out the steps the customer takes to get the job done. Then remove steps until you reach the simplest possible process.

Identify which factor is most impeding your users. Is the mental effort needed to use your product too high? Is the user in a social context where the behavior is inappropriate? Is the behavior so different from normal routine that it’s offputting?

Variable Reward

To build a habit, your product must actually solve the user’s problem so that the user depends on your product as a reliable solution. The benefit the user receives is the reward.

Variable rewards are more effective than fixed rewards. Fixed rewards don’t change at all, delivering the same reward at unchanging intervals. Variable rewards are more like slot machines, delivering unknown amounts at an unknown frequency. Unpredictable reward sizes and novelty spike dopamine levels, which in turn strengthen the development of the habit. Imagine a slot machine that merely paid you $0.99 every time you wagered $1.00 - how fun would that be?

There are three types of variable rewards:

- Rewards of the Tribe

- We generally want to feel accepted, attractive important, and included. When other people give us social validation, this is a powerful reward.

- Rewards of the Hunt

- Before inventing tools, humans hunted animals through persistence hunting, out-enduring larger animals that couldn’t effectively cool themselves over hours of chase.

- This selected for the dogged determination to acquire rewards that aid our survival, including food, cash, and information. We are even conditioned to enjoy the pursuit itself, on top of the material rewards.

- Rewards of the Self

- We seek mastery and completion. We are driven to conquer obstacles and complete obstacles, becoming more capable than we were before.

Investment

The more effort we put into something, the more we value it, and the more likely we are to return. Thus, to encourage a user to return and build a habit, prompt them to put something of value into the system so that they value the app more highly and pave the way for longer-term rewards.

Often the user’s investment increases the value of future rewards, building a virtuous cycle of usage that becomes ever more valuable.

Here are examples of types of user investments, with explanations of how they improve future rewards and enable triggers:

- Content Curation: when users curate content they like, the product can surface more content the user is likely to enjoy through customization.

- Data: when users contribute personal data, the product can issue useful recommendations by analyzing the data.

- Social Connections: when a user connects to other users, the contributions of other users provide more value and are compelling triggers to return.

- Reputation: when users build reputations on a site, their influence increases, and their desire to leave decreases.

Introduction

Modern technology has us addicted to its use. Cognitive psychologists define habits as “automatic behaviors triggered by situational cues,” and app/tech product usage clearly qualifies in many cases.

Companies that are better at building usage habits are at a clear economic advantage. When hooked, users return to a product without expensive marketing - they return on their own volition, spurred by internal triggers rather than external prompting. People who feel lonely automatically open Facebook. Employees who want to procrastinate automatically open their email. Better access, data, and speed are making things more addictive.

The Hooked model of habit formation consists of 4 steps that form a sequence in a loop:

- A trigger prompts the behavior.

- Triggers can be external or internal. External triggers come from outside a person’s thinking (e.g. phone notifications or seeing an advertisement). Internal triggers are internal drives (e.g. relieving boredom or loneliness).

- For products, behaviors often begin with external triggers. Then, as the habit forms, the behavior becomes associated with internal triggers.

- The trigger prompts an action, which is a behavior done in anticipation of a reward.

- An action is more likely when there is motivation to do it, and when it is easier to do.

- The action delivers a variable reward.

- Predictable rewards don’t cause cravings. You don’t crave turning on your faucet since you know what happens every time.

- In contrast, variable rewards prompt more intense dopamine hits and push the user to desire the next hit.

- In completing the action, the user invests in the product, improving her future experience and increasing the likelihood of completing another loop in the future.

- Investments include inviting friends, storing data, building a reputation, and learning to use features.

One step of the loop essentially forms one user session. The user returns when prompted by a trigger (external or internal). Over time, the user associates her problem with the solution, and whenever the problem appears, she will automatically seek the solution out of habit.

We’ll be breaking down each of the steps in a chapter.

Chapter 1: Why Habits are Powerful

Habits are a way for the brain to conserve resources by executing automatic behaviors without thinking hard about it. Habits are established when the action has continuously solved the problem in the past.

When you get ready for bed, you execute a specific sequence of actions that you don’t have to think very hard about. Likewise, when you feel bored, you may execute a habit of turning on your phone and swiping up to refresh your feed, since this was an effective way of combating boredom in the past.

Habits are valuable for companies because:

- Habits increase lifetime value (LTV).

- The more they use a product, the more purchases they make and the more ads you can serve.

- Habits provide pricing flexibility, allowing companies to charge more as users deepen their habits.

- A “smile graph”, with % of signups on y-axis and time on the x-axis, shows an initial plummet but an increase as time passes and habits deepen.

- Habits increase likelihood of word-of-mouth and decrease the viral cycle time.

- More frequent users initiate more behavior loops in less time for more people (e.g. tagging friends in a Facebook photo).

- A big part of Facebook’s domination over MySpace and Friendster could be due to deeper engagement (due to the use of real identity and features like the Newsfeed) and faster organic growth.

- Habits form competitive moats, preventing customers from leaving even to superior products.

- People fall back to old habits easily, with etched neural pathways ready to be reactivated.

- Even if Bing were better than Google in finding results, it can feel slower because you’re unfamiliar with its interface.

- New products need to be 10x better to break ingrained behavior.

When Do Behaviors Become Habits?

Habits are more likely to be established when the action is more frequent and when the perceived utility is higher. Google quickly became a habit since searches happen on a daily basis, and its search results were much more useful than competing search engines.

For infrequent actions to become habit, the user must perceive a high degree of utility. This applies to purchasing items and large transactions.

- To provide more utility to the user, retailers like Amazon show ads for direct competitors, sometimes with cheaper prices than what Amazon has. While this might seem short-sighted (the user can buy with the competitor), the long-term game Amazon is playing is to associate itself with solving the problem of shopping. Users build loyalty to Amazon for being the place to start shopping. Other marketplaces like Kayak and vendors like Progressive Insurance have used this strategy with positive results.

Some behaviors never become habits because they don’t occur frequently enough - you don’t really have a house-buying habit if you buy a new house every 10 years.

Is it better for your product to be a painkiller (solving an obvious pain point) or a vitamin (nice-to-haves, appealing to emotional needs)? While classically investors prefer the former, some of the largest companies - Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram - don’t seem to be solving “real” pain points - getting social validation isn’t nearly as important as feeding yourself.

Products can begin as vitamins but, once the behavior is ingrained, they become pain remedies, removal of which becomes painful. Similarly, when people first heard of Facebook, they likely didn’t think they needed it in their lives; but a few years later, many find the news feed indispensable and addictive.

Exercise: Consider Your User’s Habits

Think about the habit that you want your users to build.

What problems do you solve for your user?

How do users who don’t currently use you solve that problem?

How much utility do you provide over the alternative?

How often do you expect the user to use your product to solve their problem?

Chapter 2: Trigger

The next 4 chapters cover each step of the Hooked model for habit-forming products.

The chain reaction that starts a habit always begins with a trigger. Habits form like pearls in oysters. It starts as a tiny irritant, like a piece of sand, triggering continuous layering of coats to produce a pearl (a fully formed habit).

External Triggers

External triggers are delivered through the environment. They contain information on what the user should do next, like app notifications prompting users to return to see a photo.

Types of external triggers include:

- Paid triggers like advertising and marketing

- Habit-forming companies tend not to rely on paid triggers since paying for reengagement is often financially unsustainable.

- Earned triggers like PR, app store placements

- Relationship triggers like word-of-mouth and social signals

- Paypal’s message about “money waiting for you” was irresistible

- Owned triggers - the user consents for the product to occupy her attention space

- App notifications on the phone, email newsletters

Internal Triggers

Over time, as a product becomes associated with a thought, emotion, or preexisting routine, users return based on internal triggers. Emotions - especially negative ones like boredom, loneliness, confusion, lack of purpose, and indecisiveness - are powerful internal triggers. These triggers may be short and minor, possibly even subconscious.

- Loneliness triggers Facebook to provide social “connection”

- Boredom prompts finding novel content on Youtube or Buzzfeed

- Lack of purpose, or the feeling that no one needs us, prompts email checking

When triggered, we often execute a mindless action to ease the negative sensation.

Discover Your User’s Pain

To build a habit, you need to solve a user’s pain so that the user associates your product with relief.

The needs that users seek to solve are often timeless and universal. Said Ev Williams of Twitter, “We often think the Internet enables you to do new things - but people just want to do the same things they’ve always done.”

To make the user’s pain feel real, build a persona of user problems. This takes the form of a specific person of a certain demographic who feels and behaves a certain way. (e.g. “Mary is a stay-at-home mother in Wisconsin who doesn’t have time to feed her 3 kids after work.”) This persona provides a rallying force for the entire team to do the right things to solve the problem.

To discover the root problem, ask “Why?” as many times as it takes to get to an emotion. Example for professional email:

- Julie uses her email for work.

- Why? She wants to send and receive messages.

- Why? She wants to exchange information.

- Why does she want to exchange information? Information lets her do her job better.

- Why does she want to do her job better? She wants to get good reviews and a promotion.

- Why does she want this? She fears that she’s not good at things, and she wants validation that her talents are useful.

Now that you’ve uncovered this fear, you might design your product around the core pain point. For instance, you could highlight emails featuring positive feedback and allow her to sticky encouraging emails for motivation.

Naturally, people have different motivations for the same behavior (like checking email), so you could create multiple viable personas. People may use email to reduce FOMO, seek social connection, or avoid boredom. You’ll need to research your users and figure out which personas are most likely to use your product..

Exercise: Create Your Triggers

Think about your user’s pain points to create the best product.

Write 3 internal triggers that could remind your user to take action with your product. Write them this way: “every time the user [internal trigger], she [first action].”

What is the user doing right before using your product?

Given this, what are the best places and times to send an external trigger?

Think of 3 external triggers you could use. Then think of 3 outlandish external triggers (e.g. brain implants, electric shocks).

Chapter 3: Action

After the trigger, the user needs to perform the desired action.

To initiate action in a habit, doing must be easier than thinking. An action has three requirements:

- Sufficient motivation

- Sufficient ability

- A trigger to activate the behavior

Consider how you behave when you hear your phone vibrate. The trigger is there, but you might not have the motivation (it’s the end of the day and you want to shut the world out). Or if the phone is buried at the bottom of your bag, you have insufficient ability to get the phone. And if the phone is muted, you have no trigger to activate the behavior.

Motivation to Take Action

Motivation is the “energy for action.” All humans are motivated to:

- Seek pleasure and avoid pain

- Seek hope and avoid fear

- Seek social acceptance and avoid rejection

Advertising commonly employs these desires.

- Obama’s 2008 campaign posters inspired hope, and publicly belonging to the movement incurred a feeling of social acceptance.

- Sexual imagery is used often, from Victoria’s Secret to Carl’s Jr. (though the target market needs to associate sex as a motivator, like teenage boys).

- Budweiser rarely advertises the beer, instead showing men bro-ing out, associating the beer with good times. Coca-Cola is similar, showing friends and families having a good time.

- Using negative emotions as cautionary tales also works, invoking pain, fear, and rejection if you don’t buy this product.

Ability to Take Action

Ability is the capacity to do a behavior.

Make the process to use your product as simple as possible. Lay out the steps the customer takes to get the job done. Then remove steps until you reach the simplest possible process.

Web technology inexorably moves toward making activities easier. The lower-friction products are usually the ones that win.

- In content generation, consider how the web was largely read-only, consisting of professional media companies.

- Then the development of Blogger and Xanga let amateur writers publish easily, without knowledge of content management systems or servers and without going through a traditional media company.

- Then with the advent of easy publishing tools like Twitter and Pinterest, the friction to write and create new media shrank even further.

Though critics once decried Twitter’s 140-character limitation, what they missed was how this constraint lowered the barrier for participation, prompting many more to engage. (Shortform note: similarly, Snapchat’s ephemeral messaging lowers the barrier for messaging, compared to a permanent high-quality medium like Instagram.)

Said Ev Williams of Twitter, “Take a human desire, preferably one that has been around for a really long time...identify that desire and use modern technology to take out steps.”

How to Simplify Your Action

Behavioral scientist B. J. Fogg describes six factors that influence a task’s difficulty:

- Time

- Money

- Physical effort

- Mental effort

- Social deviance

- Non-routine - “how much the action matches or disrupts existing routines.”

(Shortform note: some of the largest web companies have reduced one or more of these factors by multiples, or even orders of magnitude:

- Compared to calling 50 separate friends or sending mass emails, Facebook reduces time and effort to broadcast your personal news. It also became socially acceptable to broadcast good personal news on Facebook, when at one point it might have been considered socially gauche.

- Compared to hailing a cab or driving, Uber reduces the time, money, physical effort, and mental effort considerably.

- Compared to shopping in physical stores, Amazon reduces the first 4 considerably, and also matches existing routines of shopping.

Furthermore, each of these roughly matched routines that people had previously done - Uber fit people’s prior habits behavior of getting into strangers’ cars, and Amazon fit user’s behaviors of shopping in physical stores.)

Identify which factor is most impeding your users. Is the mental effort needed to use your product too high? Is the user in a social context where the behavior is inappropriate? Is the behavior so different from normal routine that it’s offputting?

Here are examples of tactics to reduce frictions:

- Log in with Facebook, rather than type in email and password

- Share a page with an embedded Tweet button, rather than go to Twitter.com and copy text over

- Google’s homepage is simple and clear. The search has auto-suggest, spelling correction, and instant search results, reducing mental effort and time to get results.

- The iPhone has the camera button on the homescreen, reducing the friction to taking photos.

- Pinterest has infinite scroll, reducing the physical effort needed to view more content.

- Change your landing page or homepage to direct users to the action you want them to take.

- Twitter changed from a search form to creating an account or downloading the app.

Should you start with increasing ability or motivation? The author argues, “always start with increasing ability.” Motivating users is hard - users don’t read text, and they have deeply ingrained behaviors. Reducing the effort to perform an action gets them to the reward more quickly.

Shortcuts to Increase Motivation

Cognitive biases affect all of us, causing things to see things as quite not objective. You can use cognitive biases and heuristics in your favor to increase motivation:

- Scarcity effect - the less of something there is, the more valuable it seems.

- In an experiment, people were shown two jars with different numbers of cookies - one jar had 8, and the other had 2. They were identical cookies. People valued the cookies in the jar with 2 more highly.

- Amazon shows “only 9 left in stock.”

- Flights show “only 5 seats left at this price.”

- Framing effect - the context around something changes its perception.

- Price affects your experience of wine.

- Violin master Joshua Bell played in a DC subway station. He was summarily ignored, because the context of the subway station made the idea of a virtuoso playing there improbable.

- Anchoring - people over-weigh the first piece of info they receive.

- A starting price in negotiation often forms the centroid of movements. A higher number offered first will stretch the final negotiation price higher.

- When asked to estimate a number product, those who see 1x2x3x4x5 estimate lower numbers than those who see 5x4x3x2x1

- Endowed progress - you complete more progress when you feel you have already made some progress.

- For punch cards, customers were given a card with 10 slots and 2 already punched in showed an 82% higher completion rate than customers given a blank card with 8 slots.

- LinkedIn shows a progress meter in completing the profile - even when just joining, the bar is somewhat filled in/

Exercise: Reduce Your Barriers to Action

Reduce the frictions for your user to take action.

Walk through how your user goes from trigger to action to reward. How many steps does the user need to take? How could you get rid of any steps?

Which of these 6 factors is most limiting your users’ ability to take action? (Time | Money | Physical effort | Mental effort | Social deviance | Non-routine)

How can you reduce that factor?

How can you use cognitive biases to increase motivation to take action? (e.g. promote scarcity, give endowed progress.)

Chapter 4: Variable Reward

To build a habit, your product must actually solve the user’s problem so that the user depends on your product as a reliable solution. The benefit the user receives is the reward.

When a habit is established, the user comes to crave the solution before actually receiving the reward. In the brain, the nucleus accumbens is responsible for dopamine signaling to reward behavior and set habits. Brain imaging studies have found that signaling was activating not when actually receiving the reward, but rather in anticipation of it.

Importantly, variable rewards are more effective than fixed rewards. Fixed rewards don’t change at all, delivering the same reward at unchanging intervals. Variable rewards are more like slot machines, delivering unknown amounts at an unknown frequency. Unpredictable reward sizes and novelty spike dopamine levels, which in turn strengthen the development of the habit. Imagine a slot machine that merely paid you $0.99 every time you wagered $1.00 - how fun would that be?

The idea of variable rewards was famously studied by Skinner, who experimented with animals pressing a lever to receive food. In the variable group, each lever press was given a random amount of food at random intervals. Animals in the variable group dramatically increased the number of times the animal pressed the lever.

Similarly, products with predictable, finite variability are far less engaging than those with unpredictable, infinite variability. How often do you rewatch your favorite movie, vs checking Facebook?

Infinite variability can often be achieved by the unpredictable actions of other people, as in multiplayer games like World of Warcraft or social networks like Facebook.

Three Variable Reward Types

There are three types of variable rewards:

- Rewards of the Tribe

- We generally want to feel accepted, attractive important, and included. When other people give us social validation, this is a powerful reward.

- Seeing others get rewards also works on us. Witnessing someone being rewarded for a particular action promotes that action within ourselves. (For instance, seeing someone get publicly praised for picking up trash will make you more likely to pick up trash yourself.)

- This works better when the people you observe are more like yourself or are more experienced role models.

- On Facebook, people clicking Like on your posts offers powerful social validation. Furthermore, Facebook automatically adjusts your content to what you engage with most, which may tend to be people who behave and look most like you.

- Rewards of the Hunt

- Before inventing tools, humans hunted animals through persistence hunting, out-enduring larger animals that couldn’t effectively cool themselves over hours of chase.

- This selected for the dogged determination to acquire rewards that aid our survival, including food, cash, and information. We are even conditioned to enjoy the pursuit itself, on top of the material rewards.

- Examples: searching for a restaurant on Grubhub uses the reward of food; gambling uses the reward of money; Twitter and Pinterest use the reward of information.

- Rewards of the Self

- We seek mastery and completion. We are driven to conquer obstacles and complete obstacles, becoming more capable than we were before.

- Games employ this by presenting difficult enemies to defeat, and rewarding progress by leveling up abilities.

- Engaging work challenges you at the limit of your abilities, leading to a state of deep concentration called flow.

Here are two examples of successful habit-forming products that use variable rewards:

StackOverflow

Tribe: good answers are upvoted by the community, validating your expertise.

Hunt: programming information is valuable to you to build useful things

Self: answering a difficult question at the limit of your ability is an engaging challenge

Tribe: requests from other people validate your importance. Information from other people makes you feel connected.

Hunt: information contained in emails help you survive better (job offers, investment status)

Self: replying to and deleting emails are fulfilling tasks. Reaching inbox zero provides a sense of mastery.

Any system of variable rewards isn’t an automatic panacea - it needs to be tied to what really, intrinsically matters to users. Q&A site Mahalo.com tried to pay users money for answering questions, but ultimately found this was insufficient motivation. If money were a primary motivation, users were better off earning a wage, as the rewards came too infrequently and were too small. In contrast, more popular sites like Quora and StackOverflow don’t pay any money, but they use the more powerful tribe rewards to drive stronger behavior.

Autonomy

In general, humans desire autonomy, the freedom to choose their own actions.

- Research found that the rate of donations from strangers increased when ending a request with the phrase “but you are free to accept or refuse.”

- Similarly, successful apps tend to give users freedom to choose what to do, rather than forcing your hand.

Threats to autonomy give rise to reactance, the adrenaline-fueled feeling when your boss micromanages you or your mom tells you to put on your coat. This increases the friction of completing a task

The author hypothesizes that part of the reason people sneak breaks to look at their phone or Facebook at work is to regain some sense of autonomy.

Exercise: Design Your Rewards

Consider how to deepen the rewards that your users get.

What reward does your product give that alleviates the user’s pain?

Does this reward trigger cravings for more? Or are users content with what they get?

Brainstorm how your product can give more Rewards of the Tribe.

Brainstorm how your product can give more Rewards of the Hunt.

Chapter 5: Investment

Investment is the last step of the 4-step model: allowing the user to invest in the product to improve future experiences.

The more effort we put into something, the more we value it, and the more likely we are to return.

Three psychological tendencies cause the investment effect:

- The IKEA effect

- Investing labor in something causes you to value it more

- Experiment: People who made origami themselves valued it 5x higher than third party bids.

- Consistency bias

- We want current behavior to be consistent with past behavior

- Experiment: People who were asked to place a window sticker for a political cause were then 4x more likely to place a large yard sign, compared to people who were asked to place a large yard sign upfront.

- Cognitive dissonance

- If you dislike an action you’re doing, you have dissonance in your mind - “why am I doing this if I hate it?” To resolve the dissonance, you tend to value the action: “I must actually like doing this for me to continue doing it.”

- Acquired tastes like spicy food and bitter beer may stem from this. “This tastes bad, so why am I eating it? Well I must actually enjoy it.”

- (Shortform note: Ben Franklin gave advice on how to get people who don’t like you - ask them a favor. If they do you the favor, they resolve the cognitive dissonance by believing they liked you more than they previously thought.)

Thus, to encourage a user to return and build a habit, prompt them to put something of value into the system so that they value the app more highly and pave the way for longer-term rewards.

Often the user’s investment increases the value of future rewards, building a virtuous cycle of usage that becomes ever more valuable. The extra value can come from personalization through data or enhanced user abilities. Furthermore, the user’s investment increase the switching costs to using a rival product - it means forsaking everything they’d built up.

Even better, the user’s investment allows for personalized external triggers based on the user’s past behavior.

How to Build User Investments

Here are examples of the types of user investments, with explanations of how they improve future rewards and enable triggers:

Content Curation

The idea: when users curate content they like, the product can surface more content the user is likely to enjoy through customization.

- In iTunes and Spotify, users add songs to their collection. The services learn the users’ preferences and surface more music they’ll like. Introduction of new music provides triggers for users to return.

- In Facebook, people’s digital lives are largely catalogued in the timeline - photos, videos, status updates, articles shared, friends’ content liked. Facebook learns the user’s preferences and surfaces content that encourages more engagement. New social content is a compelling trigger to return.

Data

The idea: when users contribute personal data, the product can issue useful recommendations by analyzing the data.

- In LinkedIn, users offer their own personal employment data as a virtual resume. Adding more details increases the likelihood they can gain contacts or job opportunities. Connection requests and profile views are triggers to return, engage, and further improve their profile.

- In Mint, users contribute financial data to supervise cashflow in one place. Adding more financial accounts allows Mint to provide more helpful recommendations and enables features like budget setting. Useful triggers arise when budgets are broken, suspicious transactions are detected, or ways to save money appear.

Followers and Social Connections

The idea: when a user connects to other users, the contributions of other users provide more value and are compelling triggers to return.

- In Twitter, people follow other accounts to personalize content (see “content curation” above) but also collect followers if they are active tweeters. Having more followers makes every tweet more impactful as a content creator. Triggers arise when you post content that followers reply to and retweet.

- In Tinder and any dating app, users express preferences for each other. More usage allows the app to deliver people you’re more likely to have romantic success with. Triggers arise when people you’re interested in also express interest in you or send messages.

- In Snapchat, texting, and messaging in general, the barrier to responding is very low. Adding a friend in one messaging app makes it more valuable for both people (Metcalfe’s Law). Triggers arise when you receive messages from people you care about.

Reputation

The idea: when users build reputations on a site, their influence increases, and their desire to leave decreases.

- In eBay, Yelp, and Airbnb, building a strong reputation as a vendor increases your customer flow. Maintaining a 5-star rating takes serious work, which makes highly-reviewed services all the rarer and more valuable. Triggers arise when threats to reputation like bad reviews appear.

- In Reddit, Quora, Stackoverflow, and forums, users accumulate points and status for being of value to the community. Higher reputations make your contributions seem more valuable, and thus contribute further to your reputation.

Skills

The idea: For highly technical software like Photoshop and Salesforce, using the product requires great time and effort. Investing more time unlocks new capabilities that produce better results, in the form of better looking images or more sales closed.

Triggers are less natural here, but may arise through product updates or as result of the output (eg changes in sales lead status).

Reminders

The idea: explicitly asking the user to set reminders for herself is a form of investment and rewards.

- In Any.do, users make to-do lists. The app asks the user to connect to their calendar, which provides a trigger: right after the next meeting ends, Any.do prompts the user to record any follow-up tasks.

In every one of the above, notice how the switching costs are incredibly high after investing a lot of effort. Thus each service has a natural defensible moat from competitor attack.

Furthermore, note how all of the above tend to have virtuous cycles or flywheel effects - because the product gets more valuable with more investment, the user wants to return and use it more, which further increases the product value.

Caveat: because investment increases friction, ask users to do work after they’ve received the variable rewards, not before. And to prevent scaring users away, stage the investment into small chunks of work, starting with small, easy tasks and building up complexity over successive cycles.

Exercise: Build User Investments

Get your users to invest in your product by taking action.

What investment does the user do to add value to a future experience?

In your product, how can you add investments in content curation, data, reputation, skills, or reminders? List all the ideas.

Chapter 6: Building Habits Responsibly

With great power comes great responsibility. You’ve now learned how to build products that change people’s behaviors, be persuasive, and manipulate people into doing things they might not naturally do.

This can sound evil. Yet many successful products ranging in morality manipulate people’s behavior. Why is Weight Watchers any better than slot machines? How do we distinguish good habit forming from bad?

Hooked provides the useful Manipulation Matrix, which can help you examine whether you should be attempting to hook your users. Depending on whether you believe your product improves the user’s life and whether you use the product yourself , you fit into these profiles:

| Maker does not use it | Maker uses it | |

| Materially improves the user’s life | Peddler | Facilitator |

| Does not improve the user’s life | Dealer | Entertainer |

While your bin placement doesn’t guarantee success, morality, or market size, they do affect your chances of success. Businesses in different bins have different properties.

Facilitator

You create something you would use and earnestly believe makes the user’s life better. These tend to be healthy habits.

You cannot consider yourself a facilitator unless you’ve experienced the problem yourself.

Because you have the problem yourself, you know the user well, and are often best positioned to solve the user’s problems. This increases your chance of success.

If it’s something you would have used earlier in life but wouldn’t today, then the longer the time difference, the lower your odds of success. For instance, if you’re building a product for apartment renting, but you’ve owned a house for 10 years, you’re likely out of touch with what users want.

There is still a risk of addiction for even the most healthy products, but luckily the rate is low (<1%), and the benefits likely outweigh the cons.

Peddler

You create something you don’t use yourself, but you believe improves the user’s life.

- Don’t fool yourself - ask yourself if you honestly believe the product benefits the user’s life, or whether you’re just rationalizing something you know is bad.

Because you don’t have the problem yourself, you have to take extra leaps to imagine the user who’ll find the product valuable.

- You may also have the hubris that you can understand someone who’s unlike you, when really you may be completely off base and building something no one wants.

You operate at a heavy disadvantage because of your disconnect with your customers and their needs, which makes your product feel inauthentic. This lowers your chances of success.

Common examples include advertising to a market unlike yourself, too-good-to-be-true products.

Entertainer

If you just want to have fun, but can’t honestly claim it improves lives, it’s entertainment.

Entertainment, like art, is important, but tends to be fleeting because they don’t consistently improve people’s lives. They tend not to be habit-forming products - you can only watch a movie so many times, until you seek the next dose of novelty.

- This is why entertainment is a hits-driven business. Demands shift, become unpredictable, and don’t form reliable habits.

Sustainable businesses here come not from the content itself or the user’s habits - they arise from effective distribution to get to more users while they’re still hot, and continuous novelty to keep feeding interest.

(Shortform note: entertainment that has other variable rewards, like a social community and infinite variability, are more likely to form persistent habits - like online role-playing game World of Warcraft, or the large content library of Netflix.

Also, this categorization is subjective - some game developers are facilitators who honestly believe their games honestly improve the world, but their games are subject to the same properties as games by developers who are entertainers.)

Dealer

In the absence of both utility and self-usage, you presumably are building the product only to make money.

This can put you in morally precarious positions.

Casinos and drugs both squarely fit in this category.

Chapter 7: Bible App Example

Having understood the model of building habits, we can now dive into a single business.

The Bible App is the leading Bible app that allows users to study the Bible, providing daily snippets and reading plans as well as the full Bible text. Founded by a pastor and owned by a church group, the Bible App is squarely in the Facilitator category.

With over 200 million downloads, it received a natural advantage by being early to the new App store in 2008, but it also methodically uses Hooked principles to become a habit-forming product.

Triggers

- As a mobile app, Bible App can send notifications where desktop and static videos cannot.

- Users get regular reminders to read their daily verse and the next piece of their study plan.

- Eventually, as its users associate the app with relief, emotional discomfort can internally trigger users to return to the app.

- The app is popularly supported by pastors who can input their sermons and instruct their congregation to load up the app.

Action

- Ability

- As a mobile app, it is easily accessible in any location.

- Chunking the Bible into small sections lowers the bar for participation.

- Starting study plans with short verses and short inspirational thoughts are easier to digest.

- Putting more interesting parts of the Bible up front and saving boring parts for later increase completion rate.

- Motivation

- The Bible teaches people to have hope and overcome their fears and pains.

Variable Reward

- It’s unclear which verse you’ll receive at any time - thus it’s a delight to see what you get each day.

- The random verse can sometimes even feel like direct messages from God, when the right message comes at the right time for your problem. Few rewards from apps can really feel this powerful.

- Social features allow users to send messages to each other.

Investment

- Committing to a reading plan gives the app a compelling reason to notify the user to return and honor their commitment.

- Progress recorders tick off a calendar for each day a user successfully reads the verse.

- Users highlight verses, add comments, and create bookmarks - all investments. The app becomes their repository of life experiences and wisdom.

Chapter 8: Testing Habits with Users

Now that you have ideas, you need to test them with real users. The author proposes the Habit Testing process, similar to “build, measure, learn” from Lean Startup.

- Identify

- Define what it means to be a devoted user. How often should she use your product? What does this person do?

- Use cohort analysis to figure out how your users are meeting this benchmark.

- Nir Eyal argues 5% of habitual users is a good benchmark to exceed - fewer and you may have a problem.

- Codify

- Identify the steps your habitual users took to find patterns to what hooked them.

- Twitter found that following 30 people reached a tipping point

- Modify

- Modify the same Habit Path identified above - update the conversion funnel, remove features that block action, strengthen features that increase investment.

Discovering Habit-forming Opportunities

You might be wondering what kind of product to build and how to get your users to build habits. How can you find ideas for habit-forming experiences?

- Start with your own problems

- Ask why you do or don’t do certain things, and how you can make those tasks easier or more rewarding.

- Be aware of your behaviors and emotions as you use products.

- What triggered you to use these products? Were they external or internal triggers?

- Am I using these products as intended?

- How can these products improve their onboarding funnels, increase motivation or ability, provide better variable rewards, reengage through external triggers, or encourage users to invest in the product?

- Find what early adopters are doing

- Many inventions like airplanes, the telephone, and the Internet were mocked as unnecessary. Often it was a lack of imagination for the new possibilities.

- Early adopters show you niche use cases that can eventually be taken mainstream.

- Facebook started with just Harvard students.

- Consider what new technologies enable

- New technology waves establish an infrastructure first, enabling new applications to reach massive penetration.

- Figure out what behaviors new technologies make easier.

- The camera integrated into the smartphone made photo-taking far easier, giving rise to Instagram.

- Find how user interfaces can drive new habit formation

- Apple and Microsoft turned text-based terminals into GUIs modifiable with a mouse.

- Google simplified the search interface of Yahoo.

- Pinterest created an infinite-scrolling canvas of images that was more addictive than smaller fixed galleries..

- Consider “living in the future.”

- Ask three people outside your social circle what apps occupy their phone’s home screen. Ask them to use their favorite app and observe any nascent behaviors.