1-Page Summary

How to Read a Book is the classic guide to reading effectively. It teaches how to understand the crux of a book within 15 minutes, how to analyze a book intelligently, and how to synthesize ideas from multiple books. Reading is an active activity, not a passive one—so if you read a lot of books, it makes sense to learn how to increase the value of your reading.

Part 1: The Premise of How to Read

According to the authors, after you learn phonics as a child and go through high school English, no one really teaches you how to read intelligently. College courses rarely touch on this, and the workforce even less so. As a result, plenty of adults read at an elementary level—not in the sense of having a limited vocabulary, but in absorbing the value of a book efficiently. (Shortform note: This holds just as true today as it did in 1972. One study found that 43 million American adults have “low literacy skills.”)

The authors believe there are two types of active reading (note that this does not include reading for pure entertainment, which is a relatively passive pursuit in terms of cognitive effort):

- Reading to collect facts. The authors argue that if you understand the book completely without exerting any extra effort, then you have only gained information from the book—you haven’t improved your understanding. You’ve simply added to your existing collection of facts on the subject.

- Reading for comprehension. When you read for comprehension, the authors believe that you won’t glean all the meaning from the book on the very first try. Instead of just adding to your collection of facts on a subject, the book will challenge you to find new ways to think about those facts or relate them to one another. You’ll begin to think about not just what is the case, but why it is the case. This type of reading expands your understanding and increases your reading skills.

In 19th Century America, All Reading Was “Reading for Comprehension”

The authors believe that “reading for comprehension” is a unique type of reading, distinct from reading for information. In Amusing Ourselves to Death, author Neil Postman argues that classifying “reading for comprehension” as just one category of reading is a modern idea because, in the past, there were no alternatives: All reading was for the purpose of comprehension because print was the most accessible medium for sharing ideas. In other words, reading was such a critical part of early American society that deeply understanding what you read was crucial.

How did “reading for comprehension” evolve into its own, separate task? Postman argues that two inventions changed the nature of reading in 19th century America, the first being the telegraph. The invention of the telegraph made it possible to communicate short bursts of information across great distances. Over time, the country evolved from a slow, print-centered intellectual culture to one that valued speed and quantity of information over relevance. Reading The Federalist Papers and thoughtfully debating the contents with your family was out—glossing over eye-catching headlines of news from around the world was in.

The development of modern photography also contributed to this new hunger for information to be delivered in quick, easy-to-digest formats. Instead of slogging through a long book about life in another culture, you could glance at a photograph and immediately get a sense of another world, without all the mental effort of reading. Now, two centuries later, we spend our free time scrolling image-based social media platforms. For better or for worse, “reading for comprehension” has become an entirely separate activity that is no longer a requirement to participate in daily life.

4 Key Questions to Answer While You’re Reading

The authors assert that if you read for comprehension, you will be able to answer four key questions about the book:

- What is the overall message or theme of the book?

- This should be a quick synopsis, not a detailed summary.

- How does the author’s argument unfold?

- What are the main principles and supporting evidence?

- Is the author’s argument valid?

- Provide evidence to support your opinions.

- What are the implications?

- If you agree with the author’s argument, how will you act on it?

Ideally, the authors recommend you make a habit of asking these questions as you read. Doing this feels clunky at first, but you need to train each skill separately before doing it all subconsciously.

A Fifth Question: The Limits of a Good Idea

As you read, you may also want to ask a crucial question not posed by the authors: “What are the limits of the author’s good ideas? W

hat would happen if everyone followed this advice all the time?” It’s rare that an idea is applicable in all situations.

For example, in Smarter Faster Better, author Charles Duhigg advocates for probabilistic thinking, a decision-making strategy that requires thinking up all the possible outcomes of a given choice and then calculating the likelihood of each of those outcomes. Duhigg argues that thinking probabilistically will increase the accuracy of your predictions and lead to more productive choices. However, if everyone thought probabilistically all the time, we’d lose the ability to be spontaneous or to respond instinctively to any situation. If we thought probabilistically about whether to slam on the brakes when a dog runs into the road, the extra thinking time could have terrible consequences. Therefore, Duhigg’s good idea clearly has a limit.

“Too much of a good thing” is a particular concern in self-help books. For example, in The Game, author Neil Strauss presents tips on flirting with women from several self-proclaimed master pickup artists. However, many of these tips—like “negging” (insulting a woman with a backhanded compliment)—could easily escalate into abusive behavior. Thus, if you’re reading a book in the self-help or how-to genre, “what are the limits of this idea?” may be an especially important question to ask.

Part 2: Elementary and Inspectional Reading

So far in this guide, we’ve learned the purpose of reading well and discussed how to choose which books to read. In the next two parts, we’ll cover the first three levels of reading: elementary, inspectional, and analytical, in that order.

The authors describe elementary reading as the pure mechanical reading of text and comprehension of what the symbols literally mean. It’s the most basic form of reading that we learn to do as a child. (As an adult, you revisit the difficulties of elementary reading when you first try to read in a foreign language.) (Shortform note: The authors spend considerable time discussing the specific steps of learning to read at an elementary level. However, if you’re reading this guide, you’ve already mastered those steps. Therefore, we’ve condensed this chapter to just the information that is relevant to readers who are proficient in elementary reading and want to improve their higher-level reading skills.)

After elementary reading, the second level of reading is inspectional. According to the authors, inspectional reading is a skimming of the book to understand its main points and its structure. It aims to gain the best understanding of the book in a limited time (the authors advise setting a target for 15 minutes to comprehend a 300-page book). (Shortform note: Adler and Van Doren recommend inspectional reading as a precursor to analytical reading. However, if you don’t plan to come back and read the book analytically, you can make the most of reading it inspectionally by putting the book’s ideas into practice immediately in your daily life. That way, you’ll get the maximum benefit from the information even without a deep, analytical reading.)

Techniques for Inspectional Reading

- Read the title.

- Read the preface and the blurb.

- The author often explains what the book is about, and how to tackle it.

- Read the table of contents.

- (Shortform note: This is less effective if books obfuscate titles to generate a sense of mystery. For example, Ryan Holiday’s Ego Is the Enemy features chapter titles like “To Be or to Do?” and “Follow the Canvas Strategy.” Without reading the book, it’s impossible to get a sense of what those chapters contain.)

- Scan the index for a range of topics covered. More important topics will have more pages.

- Find the main chapters of the book, and read the summary areas of those chapters.

- The summary areas are often at the end of the chapter or the end of each major section.

- Flip through the book to get a general sense of the book’s pacing and how the author’s argument will unfold.

- (Shortform note: This list of techniques is not exhaustive and doesn’t take into account 21st-century resources like online reviews and summaries. To take advantage of these new resources, try reading the top Amazon reviews of the book or scanning through one of our book guides to get a sense of the book’s main arguments. Additionally, you may want to read the book’s introduction and spend time looking at any charts, graphs, or images.)

Part 3: Analytical Reading

According to the authors, the aim of analytical reading is to, without imposing any time restraints, gain the best understanding of the book possible. Not only should you aim to understand what is being said, but you should also develop a personal opinion about its validity. (Shortform note: In addition to forming a judgment about the book’s validity, you might think about what parts of the book were most impactful and will stay with you over time.)

Adler and Van Doren believe the first step of analytical reading is to understand the author’s goals in writing the book. This requires finding out what problems the author is trying to solve and what questions the book tries to answer. (Shortform note: This task is a bit more complicated for fiction works, as different readers can come away with different understandings of the author’s intent.)

How to Find Keywords

In the step above, you figured out what questions the author is trying to answer. Now, Adler and Van Doren argue you need to comprehend what the book is actually saying, and what arguments the author makes in relation to her questions. To find what the book says, Adler and Van Doren advise looking for keywords. Keywords are meaningful words or phrases that are used often and convey a wealth of information. As a reader, you need to understand the keywords of the author and what is meant by them. This is especially important because the same word can mean different things to different authors.

(Shortform note: Be sure to look for keywords early in the revision process, otherwise you may misunderstand the author’s arguments in the rest of the book. For example, in A Brief History of Time, author and physicist Stephen Hawking uses the word “theory” in a very specific, scientific way, not in the colloquial sense as a simple synonym for the word “idea.” To really understand the rest of the book, it’s crucial to understand how Hawking defines that keyword.)

How do you find keywords? Adler and Van Doren provide two clues to identifying the most important terms in a book. First, a word is probably important if the author deliberately uses it differently than other writers do (particularly if the author makes a point to explain why those other writers’ definitions are incorrect or incomplete). Second, if you struggle to understand how an author is using a particular word, that’s a sign that the word is important: Authors frequently use keywords in unique ways to express their most important (and, often, most complex) ideas.

More Tips on How to Find Keywords

The process of finding keywords in a text can differ based on the type of text and the way you approach it. For example, shorter works like articles often feature keywords in predefined places—such as the first sentence of the article, the last sentence of the first paragraph, and in any repeated phrase throughout the piece.

Additionally, if you already know something about what you’re reading, that can help you identify the keywords. For example, if you’re reading Darwin’s The Origin of Species, you probably know that Darwin’s ideas were part of the theory of evolution, so you’ll know to keep an eye out for “evolution” as a keyword. You can also look for synonyms and related words or phrases, like “heredity” or “survival of the fittest.”

How to Find Key Sentences

After identifying keywords, Adler and Van Doren recommend finding the author’s leading propositions in her most important sentences. Important sentences express parts of the author’s argument. Here are some tips on how to find them:

- Special sentences may be formatted stylistically or set apart (for example, with italics or underlining).

- The important words are often contained in the important sentences. Therefore, if you spot a keyword, pay special attention to the sentence it’s located in.

- Pay attention to words that confuse you, rather than words that grab your interest. (Shortform note: Remember, the goal of analytical reading is to increase your understanding. It’s perfectly fine to pause at a particularly interesting or entertaining sentence—but if your goal is to better understand the author’s ideas, your time is better spent wrestling with sentences you don’t immediately understand.)

Finding Key Sentences in the Digital Age

In the modern era, there are other, high-tech ways of identifying important sentences that Adler and Van Doren couldn’t imagine in 1972. For example, computer programmers in the field of natural language processing have developed algorithms capable of reading digital text and automatically identifying key terms and sentences. This is especially impressive because the program is partly based on the frequency of a given word in a text, but it has to distinguish between common-but-not-useful words (like “and” or “the”) and the actual keywords of the text. Once the program identifies the keywords based on frequency, it scans every single sentence and highlights those sentences with higher proportions of keywords—which is essentially a computerized version of the process that Adler and Van Doren recommend.

Criticizing a Book

So far in the reading process, if you’ve been following Adler and Van Doren’s advice, you’ve been absorbing what the author has to say without criticism or judgment. However, once you fully understand a book, you have a new responsibility as a reader: to argue with it.

According to Adler and Van Doren, when criticizing, your job is to determine which of her questions the author has answered, which she has not, and decide if the author knew she had failed to answer them. (Shortform note: As you begin this process, you may also want to think about the subject as a whole and ask yourself: Are there any important ideas the author didn’t mention? Did she leave anything out? If so, how would that missing information change your impression of her argument?)

Complete Your Understanding First

Much like having a conversation with an author, Adler and Van Doren contend that you need to give the author the chance to express herself fully before passing judgment. If you interrupted the author at each sentence to say she’s wrong, you’re not having a conversation that can lead to learning. Therefore, you must finish the other tasks above (outlining the book, defining main terms, understanding the main arguments) before criticizing. Otherwise, your criticism will be meaningless because you won’t be criticizing the author’s actual argument.

(Shortform note: You’ll need to use your own best judgment to decide if you fully understand the author’s arguments. However, if you’re new to the book’s subject, you should be especially cautious about deciding you understand because the less you know about a subject, the more likely you are to overestimate your understanding. This is the essence of the Dunning-Kruger effect.)

How to Criticize Well

In Adler and Van Doren’s view, criticizing a book means to comment, “I agree,” “I disagree,” or “I suspend judgment.”

When you’re criticizing an author, Adler and Van Doren caution against being overly contentious or combative. A discussion isn’t something to be won: It’s an opportunity to discover the truth. Remember that disagreement is an opportunity to learn something new. Here are some tips for keeping an open mind:

- Do not play devil’s advocate by default. Don’t resent the author for being right or teaching you something new. (Shortform note: You may be especially tempted to resent the author when they challenge one of your political or religious beliefs. Studies have shown that these beliefs are the most resistant to change because they’re intimately tied up with how we see ourselves.)

- Only agree with the author if you’ve fully evaluated their work; don’t just assume the author is right because they’re smart. (Shortform note: This may be even harder (and thus even more important) for authors you respect and admire, as you might naturally evaluate those authors’ arguments less rigorously than authors with whom you disagree.)

- Separate your emotional reaction to the book from the rational one.

- As you read, earnestly try to take the author’s point of view.

Resolving Difficult Conversations With the Author

Separating your emotional reaction to a book from your intellectual reaction and trying to take the author’s point of view isn’t always easy, especially if the author’s argument threatens an aspect of your life or your identity. In that situation, it may help to think of yourself as entering into a difficult conversation with the author.

In Difficult Conversations, authors Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen offer advice for navigating these types of conversations:

Remember that our individual experiences shape how we see the world. That means that whatever the author is saying probably isn’t meant as an attack on your principles or your identity; it’s a reflection of their own life experiences. Keeping this in mind can help you not take the author’s ideas personally.

Acknowledge and express the feelings that come up as you read—otherwise, they’ll fester and keep you from evaluating the book with a clear head.

Try out the “And Stance,” in which you acknowledge that several things can be true at once. For example, you might say, “This author has some good ideas, and some of her views are deeply intolerant” or “I’m a good person, and I’m guilty of the behavior this author is criticizing.” This allows you to see the bigger picture, not just the most difficult part.

Part 4: Comparative Reading

The first three levels of reading all focus on reading a singular text. Now, we’ll talk about applying those analytical skills across a multitude of texts. Adler and Van Doren call this “syntopical reading.” “Syntopical” is a neologism Adler’s Encyclopedia Britannica team invented; for simplicity, we’ll call this type of reading “comparative” reading.

Comparative reading aims to compare books and authors to one another, to model dialogues between authors that may not be in any one of the books. (Shortform note: In How to Read Literature Like a Professor, author Thomas C. Foster describes “intertextuality,” which is the common references and themes that exist across fiction books. Reading literature with an intertextual lens is similar to reading expository books comparatively.)

The ultimate aim is to understand all the conflicting viewpoints relating to a subject. Here are the major steps of comparative reading according to the authors. (Shortform note: Adler and Van Doren list these as a set of five steps, each containing many sub-steps. For clarity, we’ve expanded the list so that each step is one distinct action. See our full guide for specific tips on reading books in various genres, like fiction, science, and philosophy.)

1. Create a total bibliography of works that may be relevant to your subject.

- Many of the important works may not be obvious, since they may not have the keyword in their titles. (Shortform note: In established fields, look for a primer or brief history of your subject. This will give you an overview of the topic and help you identify additional sources.)

2. Inspect all of the books on your bibliography to decide which are relevant to your subject, and to better define the subject.

- As you research, you may find that your subject is more difficult to define than you imagined. For example, if your subject is World War II, you’ll have more material than you could possibly read. As you begin reading, the authors recommend narrowing down your subject.

- (Shortform note: The ultimate scope of your topic depends on your project. If you love history and want to know everything there is to know about World War II, you might keep the subject broad and make it a lifelong reading project. On the other hand, if your goal is to write a paper for a class, you may want to keep narrowing until you have just enough information to fill a set number of pages.)

3. Go through each book on your list and mark specific chapters or passages you intend to use.

- Keep in mind that only a portion of any given book may be relevant to your purposes. If you plan to read the whole book, read it quickly.

- You may use a syntopicon that organizes passages across works by subject, like Great Books of the Western World. (Shortform note: The “Syntopicon'' is a directory of “Great Ideas'' that includes every reference to those ideas across 431 “Great Books.” It took Adler and his team over 400,000 hours of reading and more than a decade to create.)

4. Develop a set of common terms and rephrase each author’s argument in that language.

- Authors in different fields may use entirely different terms that mean the same thing, and the same terms in different fields may mean entirely different things. (Shortform note: For scientific or technical topics, you may need to literally translate the author’s conclusions into a set of common units.)

5. Develop a set of questions that each author provides answers to.

- This may not be explicit—you may have to infer the author’s answer to a question she never directly considered. (Shortform note: Take your inferred answers with a grain of salt. Even if you’re well-versed in the work of a given author, it’s impossible to know for sure how that author would feel about a subject they never addressed.)

6. Get a sense of the complexity of the issues.

- See how each author answers the questions. If their answers are vastly different, it probably means that your question represents a particularly contentious issue in their field.

- (Shortform note: Another clue that you’ve stumbled on a contentious issue is if a lot of literature is published on that topic in a short amount of time (because authors are constantly rebutting each other). More informally, you may even look to social media or interviews with the authors to see whether they’re focused on rebutting another author’s ideas.)

7. Order the questions and issues to throw maximum light on the subject.

- Show how the questions are answered differently and say why.

- Avoid trying to assert the truth or falsity of any view—this fails the goal of the syntopic reading to be objective. According to the authors, full objectivity is difficult to maintain, and bias can show in subtle ways like the summarization of arguments and the ordering of answers. The antidote to this is constant reference to the actual text of the authors.

- (Shortform note: Keep in mind that bias can persist even when you’re actively trying to be objective. Psychologists have shown this through the Implicit Association Test, which tests implicit social biases. Participants know they’re being tested on bias (and therefore may be deliberately trying to appear unbiased), but those biases are so deeply rooted that they appear anyway.)

The authors suggest omitting imaginative works from comparative reading, because the propositions are obscured by plot and are rarely explicitly attributed to the author (a character’s speech could be satirical). (Shortform note: Including fiction in a comparative project is complicated indeed, but may still be valuable. For example, reading only historical accounts of 18th century English and Irish politics without reading Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (or of ancient Greece without reading the works of Homer or Sophocles) would be a major omission, despite the influence of fiction.)

Comparative Reading vs. Literature Review

In academic settings, literature reviews are a common undertaking. Literature reviews are similar to comparative reading projects in that the goal is to gain a wide understanding of what other thinkers have to say about a certain subject. Researchers conducting literature reviews often complete extra steps that Adler and Van Doren don’t mention in their discussion of comparative reading; however, these steps might be useful for comparative reading projects. For example:

Define your inclusion criteria. Literature reviews have strict inclusion criteria to help determine which sources to use. For example, many literature reviews only pull sources from academic journals, not popular press books or even textbooks. If you need to narrow down your comparative reading bibliography, you might set similar parameters on the types of sources you want to use.

Create a table to keep track of different authors’ viewpoints. This will help you keep all your information in one place as you work through your bibliography. You can even color code authors who are in favor of a certain issue or against it.

Analyze the quality of your source. For scientific topics, researchers can do this mathematically by analyzing effect size and statistical significance. For qualitative topics, you might do this by researching the author. What is their experience in this subject? For translated texts, you might also research the translator and the history of translation for that specific text. Are there any passages that different translators have approached differently?

Shortform Introduction

How to Read a Book is the classic guide to reading effectively. It teaches how to understand the crux of a book within 15 minutes, how to analyze a book intelligently, and how to synthesize ideas from multiple books. Reading is an active activity, not a passive one—so if you read a lot of books, it makes sense to learn how to read better and increase the value of your reading.

About the Authors

Mortimer J. Adler was a philosopher, Columbia professor, Chairman of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and prolific author of more than 50 books (imagine how many he must have read!). Adler wrote on a range of subjects including Aristotelian philosophy, liberal arts education, capitalism, religion, and morality. As Chairman, he oversaw the publishing of Encyclopedia Britannica's Great Books of the Western World series and went on to found the Great Books Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting literacy and critical thinking.

Charles Van Doren was a writer, editor, educator, and eventual vice president of Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. He is the author of six books and the editor of five (many of which were co-edited by Adler). Van Doren came from a literary family—his mother was a novelist and both his father and uncle were Pulitzer Prize-winning authors—and was a polymath, holding advanced degrees in both astrophysics and English.

In the late 1950s, Van Doren was a contestant on “Twenty-One,” a popular quiz show. He ultimately won over $129,000 (which equates to over a million dollars today). However, rumors of fraud prompted a Congressional investigation, and Van Doren ultimately admitted that the network gave him the questions and answers in advance. The 1994 movie “Quiz Show” is based on his involvement in the scandal.

The Book’s Publication

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

How to Read a Book was originally published in 1940 with the subtitle, “The Art of Getting a Liberal Education.” Mortimer J. Adler was the sole author of the first edition. This guide, however, covers the revised 1972 edition, which features a significant content expansion (the book is divided into four parts, only one of which was present in the first edition) and a new subtitle: “The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading.” The first edition of How to Read a Book was Adler’s ninth book; the 1972 edition was Van Doren’s second book. Both authors wrote extensively on the importance of books and reading (including Van Doren’s The Joy of Reading); however, How to Read a Book remains the most popular book in both authors’ bibliographies.

The Book’s Context

Historical Context

In the preface to this edition of How to Read a Book, Adler described the changes he observed in American society that prompted him to revisit the book 32 years after its original publication. First, the percentage of young people earning college degrees rose significantly during that time period (in part due to the passage of the GI Bill, which financed college education for veterans returning from World War II). Additionally, in 1970, the federal government reiterated the importance of reading when the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare announced a national “Right to Read” effort designed to improve reading education for children under age 10. Adler took this educational boom as a sign that reading well was more important than ever and decided to revamp his 1940 classic.

Intellectual Context

How to Read a Book was one of the first books to explicitly teach the art of reading for comprehension rather than speed. Its modern successors include Thomas C. Foster’s How to Read Literature Like a Professor, Steve Leveen’s The Little Guide to Your Well-Read Life, and Harold Bloom’s How to Read and Why, all of which focus primarily on works of fiction (unlike How to Read a Book, which focuses on techniques for reading nonfiction books).

The Book’s Impact

How to Read a Book became an immediate bestseller when it was first published in 1940. The 1972 revised edition has been consistently successful and was most recently republished in 2014.

In 1997, Adler wrote a companion volume to How to Read a Book entitled How to Speak How to Listen, in which he adapts his methodology for close reading to the art of spoken conversation.

The Book’s Strengths and Weaknesses

Critical Reception

The 1940 edition of How to Read a Book was critically well-received; upon the book’s release, one reviewer called it, “a serious and valuable invitation to an enrichment of personal life.”

Reviews of the 1972 revised and updated edition, on the other hand, are much more mixed. A 1972 New York Times review particularly exemplifies this tension—the reviewer said he couldn’t decide “whether to praise it or damn it.” He concedes that How to Read a Book fills an important gap in popular education (by teaching the reader how to get the most from a book) but also argues that the book is overly highbrow and ignores the quality of modern fiction. In the end, the reviewer recommends the book to those who are just beginning to read critically; however, he advises those who are already well-versed in the art of reading to “drop this book down the incinerator, throw it on the compost heap, get rid of it; then fumigate the premises and start reading as you please.”

Modern reviews of the 1972 edition are equally mixed—many praise the book for its unique approach to analytical reading but argue that it’s now thoroughly out of date and “boring.”

Commentary on the Book’s Approach

Nearly every idea in How to Read a Book is thoroughly fleshed out. Adler and Van Doren explain what their techniques are, why they’re important, and how to use them. Thus, the authors meet their goal of helping the reader wring more understanding out of the books they read.

To a modern reader, it may seem as though the authors give undue attention to some points that aren’t critical to the main argument; this is likely because society has changed significantly in the decades since the book was published. For example, the authors analyze the strengths and weaknesses of speed-reading in depth because speed-reading was part of the intellectual zeitgeist of the late 1960s and early 1970s. However, speed-reading has fallen in popularity, so the argument has lost some cultural relevance.

Commentary on the Book’s Organization

How to Read a Book is organized into four parts. Part One covers the mechanics of “elementary reading” and tips for “inspectional reading” (which is a form of in-depth skimming). Part Two covers “analytical reading,” which is the authors’ method of wringing as much understanding as possible out of a single book. Part Three offers specific advice for reading books of different genres (like philosophy, poetry, and science). Finally, Part Four covers “comparative reading,” which is the art of reading a wide variety of books on a single subject in order to fully understand that subject. The book ends with a recommended reading list.

This four-part structure is somewhat confusing because the four parts don’t directly map onto the four “levels of reading” that the authors reference throughout the book (with elementary reading and inspectional reading being compressed into one part), nor do they map onto the “four basic questions” that the authors claim a reader should ask about every book.

Our Approach in This Guide

Our guide to How to Read a Book contains six parts. Part 1 covers the basics of what Adler and Van Doren believe constitutes “good reading.” Parts 2 to 4 describe the principles of elementary, inspectional, and analytical reading, in that order. Part 5 contains specific advice for reading different genres analytically, such as fiction, science, and philosophy. Finally, Part 6 describes comparative reading, which Adler and Van Doren argue is the highest form of reading. Throughout the guide, we’ll examine the authors’ advice through a 21st-century lens to see how well it applies to modern readers.

Part 1: The Premise of How to Read

If you read a lot of books a year, then it makes sense to spend a few hours learning how to double the value from your reading. That’s the point of How to Read a Book.

According to the authors, after you learn phonics as a child and go through high school English, no one really teaches you how to read intelligently. College courses rarely touch on this, and the workforce even less so. As a result, plenty of adults read at an elementary level—not in the sense of having a limited vocabulary, but in absorbing the value of a book efficiently. (Shortform note: This holds just as true today as it did in 1972. One study found that 43 million American adults have “low literacy skills.”)

What Good Reading Is

While some consider reading to be passive in nature, Adler and Van Doren argue that reading for the purpose of comprehension is an active pursuit. This is a bit like the difference between merely hearing someone’s words and actively listening with the goal of comprehending what the words mean. If you read passively (without effort), you might register the surface level of what is said, but you won’t truly understand what the author is trying to say. (Shortform note: Studies show that reading for comprehension requires significant cognitive effort, but that this type of reading isn’t the most demanding—reading with the goal of revising the text requires even more mental effort.)

The authors believe there are two types of active reading (note that this does not include reading for pure entertainment, which is a relatively passive pursuit in terms of cognitive effort):

- Reading to collect facts. The authors argue that if you understand the book completely without exerting any extra effort, then you have only gained information from the book—you haven’t improved your understanding. You’ve simply added to your existing collection of facts on the subject.

- Reading for comprehension. When you read for comprehension, the authors believe that you won’t glean all the meaning from the book on the very first try. Instead of just adding to your collection of facts on a subject, the book will challenge you to find new ways to think about those facts or relate them to one another. You’ll begin to think about not just what is the case, but why it is the case. This type of reading expands your understanding and increases your reading skills.

However, we don’t live in a world that’s conducive to understanding.

- The authors argue that most people are not taught how to read beyond elementary school. That is, courses no longer teach how to learn more effectively by reading. This book aims to bridge this gap. (Shortform note: This is no longer the case, at least in theory. As of 2021, 41 of the 50 United States had adopted the Common Core Standards, which require instruction in both analytical and comparative reading for students in the last two years of high school. However, in practice, it’s likely that some schools are better than others at implementing these core standards, and many high school graduates may still lack critical reading skills.)

- Adler and Van Doren believe that today’s media is designed to require little deep comprehension. The data and viewpoints that we see in the media are designed to make the consumer agree with a preselected opinion. (Shortform note: Numerical data (such as percentages) might seem more objective, but that often isn’t the case. In How to Lie With Statistics, author Darrell Huff describes the many ways people manipulate numbers to support whatever conclusion they want to make, like using bad sampling practices.)

The authors feel that the best books challenge your reading ability and force you to grow as a reader. They also believe that to be well-read is not to have read a large number of books, but to have a high-quality understanding of good books. (Shortform note: There are many ways to define being “well-read.” The authors insist you can be well-read without being widely read, but they don’t attach limits to this idea. Can a reader have an intimate understanding of two great books and be considered well-read? Alternatively, would they use the term “well-read” to describe someone well-versed in the classics of just one genre, country, or subject?)

In 19th Century America, All Reading Was “Reading for Comprehension”

As we noted earlier, the authors believe that “reading for comprehension” is a unique type of reading, distinct from reading for information. In Amusing Ourselves to Death, author Neil Postman argues that classifying “reading for comprehension” as just one category of reading is a modern idea because, in the past, there were no alternatives: All reading was for the purpose of comprehension because print was the most accessible medium for sharing ideas. In other words, reading was such a critical part of early American society that deeply understanding what you read was crucial.

How did “reading for comprehension” evolve into its own, separate task? Postman argues that two inventions changed the nature of reading in 19th century America, the first being the telegraph. The invention of the telegraph made it possible to communicate short bursts of information across great distances. Over time, the country evolved from a slow, print-centered intellectual culture to one that valued speed and quantity of information over relevance. Reading The Federalist Papers and thoughtfully debating the contents with your family was out—glossing over eye-catching headlines of news from around the world was in.

The development of modern photography also contributed to this new hunger for information to be delivered in quick, easy-to-digest formats. Instead of slogging through a long book about life in another culture, you could glance at a photograph and immediately get a sense of another world, without all the mental effort of reading. Now, two centuries later, we spend our free time scrolling image-based social media platforms. For better or for worse, “reading for comprehension” has become an entirely separate activity that is no longer a requirement to participate in daily life.

4 Key Questions to Answer While You’re Reading

The authors assert that if you read for understanding, you will be able to answer four key questions about the book:

- What is the overall message or theme of the book?

- This should be a quick synopsis, not a detailed summary.

- How does the author's argument unfold?

- What are the main principles and supporting evidence?

- Is the author's argument valid?

- Provide evidence to support your opinions.

- What are the implications?

- If you agree with the author’s argument, how will you act on it?

Ideally, the authors recommend you make a habit of asking these questions as you read. Doing this feels clunky at first, but you need to train each skill separately before doing it all subconsciously.

A Fifth Question: The Limits of a Good Idea

As you read, you may also want to ask a crucial question not posed by the authors: “What are the limits of the author’s good ideas? What would happen if everyone followed this advice all the time?” It’s rare that an idea is applicable in all situations.

For example, in Smarter Faster Better, author Charles Duhigg advocates for probabilistic thinking, a decision-making strategy that requires thinking up all the possible outcomes of a given choice and then calculating the likelihood of each of those outcomes. Duhigg argues that thinking probabilistically will increase the accuracy of your predictions and lead to more productive choices. However, if everyone thought probabilistically all the time, we’d lose the ability to be spontaneous or to respond instinctively to any situation. If we thought probabilistically about whether to slam on the brakes when a dog runs into the road, the extra thinking time could have terrible consequences. Therefore, Duhigg’s good idea clearly has a limit.

“Too much of a good thing” is a particular concern in self-help books. For example, in The Game, author Neil Strauss presents tips on flirting with women from several self-proclaimed master pickup artists. However, many of these tips—like “negging” (insulting a woman with a backhanded compliment)—could easily escalate into abusive behavior. Thus, if you’re reading a book in the self-help or how-to genre, “what are the limits of this idea?” may be an especially important question to ask.

Techniques to Understand a Book

We’ll cover far more suggestions on how to read well later in this guide, but here are a few strategies Adler and Van Doren recommend, most of which relate to how you should mark up a book while reading:

- Underline, highlight, or draw a symbol to mark major points.

- Sketch out the author’s argument using numbers in the margins (for example, Point 1, Subpoint 2, Evidence 1, and so on).

- Refer to other pages in the margin.

- Write questions in the margins next to confusing or unclear points.

- After finishing the book, outline the content of the book.

(Shortform note: Adler believes so strongly in the importance of marking up books that he published a pamphlet called “How to Mark a Book'' in 1941, one year after publishing the first edition of How to Read a Book. In it, he offers a tip for taking notes on books if you’d rather not write directly on the pages: Write your notes on paper that is slightly smaller than the book pages (so the edges don’t stick out of the book), then store them in the book itself.)

The Four Levels of Reading

Adler and Van Doren divide the act of reading into four levels, each increasing in difficulty and complexity. Here they are at a high level (we’ll discuss them in detail later in this guide):

- Elementary

- This is pure mechanical reading of text—translating written symbols into meaningful words.

- Most of what you learned in school was elementary reading techniques.

- Inspectional

- This is a careful skimming of the book to understand its main points and its structure.

- Inspectional reading involves reading the table of contents, index, and key paragraphs of major chapters.

- Analytical

- This is the most thorough way to read and understand a single book.

- When reading analytically, once you understand what an author is saying, your job is to form an opinion on the validity of the work.

- “Syntopical” or Comparative

- This aims to compare books and authors to one another in order to fully understand a single question or idea. (Shortform note: This is what Shortform’s expanded book guides do. We add commentary on each unique idea within a book that situates that idea within the wider universe of ideas.)

Other Ways to Divide Reading Levels

The authors’ way of dividing reading skill into a leveled system isn’t the only way. For example, educators commonly use a three-level system to grade reading comprehension. In this system, Level 1 consists of what the authors would call “elementary” and “inspectional” reading. It’s the process of reading and understanding the literal words on the page. Level 2 is the beginning of what the authors would call “analytical” reading—readers begin to interpret the meaning of the text and answer “why?” questions about what they’ve read. The third and final level in this system, Level 3, also falls under analytical reading. At this level, readers form judgments about what they’ve read, decide whether they agree or disagree with the author, and evaluate the work’s impact on their own lives.

Similarly, there is another three-part leveling system that teachers sometimes use. In that system, Level 1 is still about the literal words on the page. Level 2, however, brings in what Adler and Van Doren would call “syntopical” reading, in which students begin making connections between what they’re reading, other books, and even their own life experiences. In Level 3, students refocus on the text at hand and begin looking for rhetorical devices (such as repetition and juxtaposition).

On What Books to Read

According to the authors, the vast majority of books will not strain your ability to read analytically. They deliver information that fits your current framework, or they are meant to be read for entertainment.

Then, there is a smaller class of books that can give you more than entertainment or information—they can actually help you live a better life. These are the books that you can read analytically, be deeply impacted by, but not necessarily feel compelled to reread once you finish them. (Shortform note: Beware—not every book that purports to teach you how to live well actually does. Many self-improvement books become popular because they are easy to read and sound like good ideas, not because they can actually help you live a different or better life.)

There is a final, highest class of books, perhaps fewer than a hundred, that you can return to over and over again and get something new out of them each time. The authors believe you should seek out these books, for they will teach you the most.

To identify these books, the authors suggest you consider the desert island question—which 10 books would you take with you if you could never read any book ever again? These are unique to us all, and you should start with the classics that interest you the most.

Consider Great Books Outside the Western Male Canon

As you read this guide, keep in mind that when Adler and Van Doren discuss “great books,” they’re referring exclusively to books in the Western canon. In an appendix, the authors acknowledge this and explain that they’ve chosen to stay within their own areas of expertise (this makes particular sense for Adler, who spearheaded the Great Books of the Western World program and is, therefore, a respected gatekeeper of the Western canon). Therefore, their recommended reading list does not feature any writers from other parts of the world. The 137 author list also features just two women: Jane Austen and George Eliot.

The classics of the Western canon are timeless for a reason. However, for modern readers, reading solely within the Western canon means missing out on the chance to read authors with vastly different perspectives. To expand your literary horizons, consider reading classic works of world literature like Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude or Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. Additionally, you might wish to explore classic works written by women like Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

>

Exercise: Reflect on Your Reading Life

If you’re reading this guide to How to Read a Book, chances are you enjoy reading great books. Reflect on your approach to reading below.

In general, what motivates you to read? (For instance, do you typically read for entertainment, to learn something new, or to increase your understanding of different ideas?)

How do you choose which books to read next? (For example, maybe you use a reading list or rely on recommendations from friends.)

Do you tend to read a wide variety of books or stick within one genre? Why?

The authors recommend asking questions of the books you read and making notes as you puzzle out the answers. Do you typically take notes as you read? Why or why not?

Part 2: Elementary Reading

So far in this guide, we’ve learned the purpose of reading well and discussed how to choose which books to read. In the next three parts, we’ll cover the first three levels of reading: elementary, inspectional, and analytical, in that order.

The authors describe elementary reading as the pure mechanical reading of text and comprehension of what the symbols literally mean. It’s the most basic form of reading that we learn to do as a child. (As an adult, you revisit the difficulties of elementary reading when you first try to read in a foreign language.) (Shortform note: The authors spend considerable time discussing the specific steps of learning to read at an elementary level. However, if you’re reading this guide, you’ve already mastered those steps. Therefore, we’ve condensed this chapter to just the information that is relevant to readers who are proficient in elementary reading and want to improve their higher-level reading skills.)

According to the authors, children learn to read quite magically. At some point words suddenly have real meaning to them. Science is not clear on how this happens. Children become more capable readers as they build vocabulary and infer meanings from context clues. (Shortform note: Some researchers believe reading comprehension has two key components: written language “decoding” skill and oral language comprehension. In other words, to read effectively, kids need to be able to translate squiggly lines on a page into a recognizable word they can say aloud and know the meaning of that word when they hear it. When both those components are in place, the metaphorical light turns on and children can suddenly get meaning from written language.)

A Note on Speed Reading

One way that adults revisit the basics of reading is through speed reading courses, which purport to teach them how to increase their reading speeds without sacrificing comprehension. According to the authors, a helpful component of speed reading is training your brain not to subvocalize (pronouncing each word in your head so that you can “hear” them in your mind). To practice this, the authors recommend this exercise: Use your hand to cover the text, and move your hand downward faster than you can currently read. Your brain will be forced to catch up.

However, after a point, reading faster necessarily trades off with comprehension. When speed reading helps you avoid spending time on texts that don’t deserve your analysis, this is good. But you wouldn’t want to speed read the Tao Te Ching.

More critical than speed reading, according to the authors, is being able to modulate your reading speed dynamically. Read certain types of texts (like fiction) faster than others that contain denser content, like science textbooks. Within a text, read key points more slowly than fluff to give yourself time to think through the logic.

Modern Science Supports Adler and Van Doren’s View of Speed Reading

The first edition of How to Read a Book contains no mention of speed reading, which wouldn’t be introduced to the American public for another 19 years. However, when Adler and Van Doren wrote the updated and revised How to Read a Book in 1972, speed reading was at the height of its popularity in the United States—even President John F. Kennedy was a vocal proponent of speed reading.

Adler and Van Doren were particularly concerned about the popularity of speed reading because they believed that, to a certain degree, speed reading and reading for comprehension are mutually exclusive. Modern science corroborates that claim—research shows that when readers double or triple their reading speed, comprehension suffers. This supports the authors’ points: When you merely need a surface-level understanding of a topic, speed reading is a helpful tool; however, if you want to truly wrap your mind around a complex idea, you’ll have no choice but to slow down.

Fortunately, there are some factors that can increase reading speed (albeit not to the extreme degrees that speed reading programs advertise) without sacrificing comprehension, such as:

Having a deep knowledge of the subject matter as well as the writing style in which it’s presented

Intense focus while reading

Continuous practice reading difficult texts

Part 3: Inspectional Reading

After elemental reading, the second level of reading is inspectional. According to the authors, inspectional reading is a skimming of the book to understand its main points and its structure. It aims to gain the best understanding of the book in a limited time (the authors advise setting a target for 15 minutes to comprehend a 300-page book).

Adler and Van Doren argue that when most people read a book, they do so cover to cover. When you read a book in that way, you’re trying to understand what a book is about at the same time you are trying to understand what the author is saying. To contrast, if you start by skimming the entire book to get a sense of what it’s about before reading from the beginning, you’ll already be in the right headspace to process the information.

(Shortform note: Adler and Van Doren recommend inspectional reading as a precursor to analytical reading. However, if you don’t plan to come back and read the book analytically, you can make the most of reading it inspectionally by putting the book’s ideas into practice immediately in your daily life. That way, you’ll get the maximum benefit from the information even without a deep, analytical reading.)

How to Read Inspectionally

After reading inspectionally, the authors believe you should be able to answer these three questions:

- What genre does the book fit into?

- What is the overall message of the book?

- How does the author develop her arguments?

(Shortform note: You may also want to answer, “How qualified is the author to write a book on this subject?” For example, a hit new business book by a relatively unknown author may be less reliable than a book by an established business leader like Sam Walton, founder of Walmart and Sam’s Club (and author of Made in America). This isn’t a hard and fast rule as good ideas can come from anyone, regardless of their external qualifications, but it can help you decide how much to buy into the author’s ideas.)

Techniques for Inspectional Reading

- Read the title.

- How helpful this is depends on the book. Some titles tell the reader exactly what to expect from the book, like Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist or Henry Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson. However, many modern titles are less explicit, like Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink.

- Read the preface and the blurb.

- The author often explains what the book is about, and how to tackle it.

- Read the table of contents.

- (Shortform note: This is less effective if books obfuscate titles to generate a sense of mystery. For example, Ryan Holiday’s Ego Is the Enemy features chapter titles like “To Be or to Do?” and “Follow the Canvas Strategy.” Without reading the book, it’s impossible to get a sense of what those chapters contain.)

- Scan the index for a range of topics covered. More important topics will have more pages.

- Find the main chapters of the book, and read the summary areas of those chapters.

- The summary areas are often at the end of the chapter, or at the end of each major section.

- Flip through the book to get a general sense of the book’s pacing and how the author’s argument will unfold.

- (Shortform note: This list of techniques is not exhaustive and doesn’t take into account 21st-century resources like online reviews and summaries. To take advantage of them, try reading the top Amazon reviews of the book or scanning through one of our book guides to get a sense of the book’s main arguments. Additionally, you may want to read the book’s introduction and spend time looking at any charts, graphs, or images.)

In school, you may have learned to look up new words or concepts as you read. However, the authors believe this will make you miss the book’s main points because you’re getting too caught up in individual words and ideas. Instead, they advise reading difficult books straight through, without pausing to look anything up. Even if you understand less than 50% of the information, this cursory reading will improve your comprehension the second time around, ultimately saving time.

Inspectional Reading Techniques Helped Obama Become the Most Well-Read President

Reading a difficult book straight through without pausing to look anything up is a familiar strategy for some well-read cultural icons. For example, in A Promised Land, former U.S. president Barack Obama describes how he relied on this technique while devouring classic books in high school. He’d circle words he didn’t know, finish the book, then go back and look those words up after reading.

This technique clearly works well for Obama, as he’s known as one of the most well-read American presidents in history and even releases an annual list of his favorite books (which, over the years, have included works like How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt and Factfulness by Hans Rosling, among many others).

In addition to making him well-read, Obama’s penchant for reading difficult books shaped him into a deft writer. In describing Obama’s first memoir, Dreams From My Father, one writer argued that “no other president has written a book that aspired to literature as clearly as Obama’s did.” This shows another benefit of reading well—it can improve your skill as a writer.

Categorizing a Book

When starting a book, Adler and Van Doren recommend figuring out what genre of book it is. This prepares you to customize your engagement with the particular type of text because you’ll want to treat a book from one genre differently from books of a different genre. For example, if you’re reading a science fiction novel, you might reasonably expect to be entertained; but if you’re reading a dense text on quantum physics, you might reasonably expect to encounter some equations and challenging ideas.

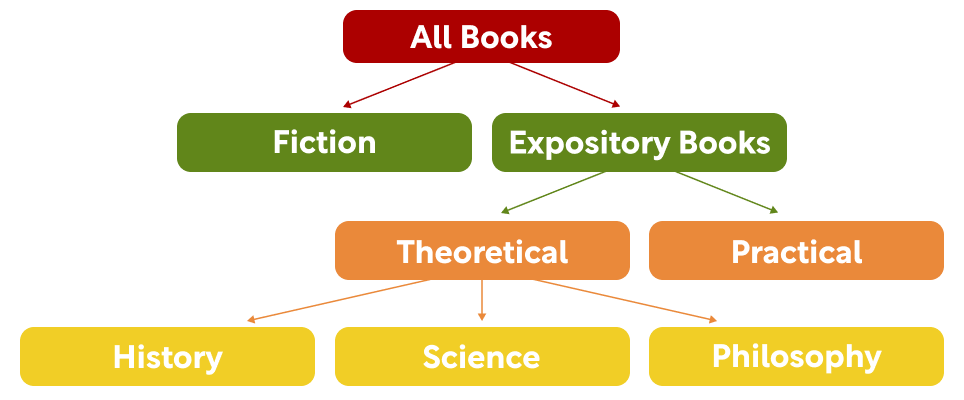

Here is the authors’ hierarchy of genres at a glance. We’ll describe each category in more detail below.

- Fiction vs Expository

- Expository books contain facts, opinions, theories, data, and so on. These books can also be called “nonfiction.”

- Theoretical vs Practical

- Theoretical works primarily provide information about a subject. The authors of theoretical works aren’t necessarily trying to persuade you to act in any particular way. Practical works, on the other hand, are written under the assumption that the reader will put the information into action. All “how to” guides (including How to Read a Book) are practical by definition.

- The authors further break down theoretical works into history vs science vs philosophy.

- History books describe a specific time and place in the past (unlike science and philosophy books, which are about universal phenomena that aren't bound to a specific historical context).

- Science deals with phenomena that you can’t observe or understand from life experience alone (for example, cellular proteins doing things unobservable to you; species evolving beyond your observable time scale).

- Philosophy deals with things you can understand based on life experience alone, without any special tools or data (such as the nature of happiness).

The Limits of the Authors’ Classification System

The broad genre categories that the authors discuss may not be a practical way to categorize all nonfiction books. For example, according to Adler and Van Doren’s classifications, many social science books would fall under “philosophy” because they deal with interpersonal relationships, which are a visible and accessible phenomenon—but social science is a distinct discipline from philosophy.

We can compare the authors’ broad approach to more specific approaches to book classification. For example, Amazon organizes its “Books” department into 32 subcategories. That level of specificity might be more helpful for books that fall outside of strict science, history, and philosophy silos.

Additionally, the authors don’t break down the “fiction” category into further subcategories in their classification system. This implies that readers should have the same approach or set of expectations for every type of fiction, from epic fantasy sagas to poetry to short stories. However, later in the book, the authors acknowledge that that isn’t the case—they provide specific tips for approaching literature, poetry, and plays.

Finally, the authors assume there is a firm, universal distinction between theoretical and practical books. While they admit that there is an occasional overlap (as in, a book that is both practical and theoretical), this may be more common now than it was when Adler and Van Doren were writing. For example, Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist appears thoroughly practical from the outset (the “how to” in the title points to this), but the book itself weaves in a heavy dose of theory, history, and even biography—none of which fall under the authors’ “practical” umbrella.

Writing a Skeleton Outline

Once you’ve skimmed through a book, the authors recommend writing out a very general overview of the book’s structure and information. They propose a methodical way to do this:

- First, articulate the thesis of the book in a sentence.

- This is easiest to do for science and philosophy books, as those authors typically lay out their entire argument in the very beginning.

- Then, construct an outline of the major parts of the book. Note how they relate to each other and to the central theme.

- Start by listing the major sections of the book; then, outline each section of the book; finally, outline each subsection.

- Not every book deserves this treatment. Adler and Van Doren advise spending less time outlining simple books and more time outlining dense, unfamiliar texts.

Some Books Resist the Skeleton Outline Approach

While Adler and Van Doren write as though all books have a single, unifying thesis, some reviewers believe that idea doesn't always apply. For example, the authors insist that this strategy applies to fiction as well as it does to expository books because the unified thesis of fiction is simply the main plotline. While this may be true for some stories (the authors cite the Odyssey as an example), it doesn’t work for books that are more character-driven than plot-driven.

For instance, if we summarized the main plot of The Catcher in the Rye in a single sentence, it would look something like, “Teenage protagonist Holden Caulfield gets expelled from school, wanders around New York City, meets up with various acquaintances, and reflects on life.” This surface-level treatment gives the reader very little useful information about the book because it ignores Holden’s internal journey as he grapples with a loss of innocence and feelings of alienation.

Part 4: Analytical Reading

So far in this guide, we’ve covered elementary and inspectional reading. Now, we’ll cover analytical reading, which is much more in-depth than the previous levels. According to the authors, the aim of analytical reading is to, without imposing any time restraints, gain the best understanding of the book possible. Not only should you aim to understand what is being said, but you should also develop a personal opinion about its validity. (Shortform note: In addition to forming a judgment about the book’s validity, you might think about what parts of the book were most impactful and will stay with you over time.)

Adler and Van Doren argue this isn’t necessary for every book, and it would be a waste of time for lower-quality books. If your goal with a book is simply information or entertainment, then you don’t need to do as thorough of a job analyzing it.

The authors argue that analytical reading consists of four components:

- Understand the author—her intentions, problems, and goals.

- Understand the author’s logical arguments.

- Use external resources, but only after you struggle through it yourself first.

- After you understand a book, criticize a book from your own viewpoint, finding areas with which you agree and disagree.

We’ll explore each of these facets in more detail below.

(Shortform note: Analytical reading is an important skill with applications beyond the realm of literature: Customer service employees who are skilled in analytical reading are better able to read and respond to all of a customer’s questions or complaints, even the implicit ones. For example, if a customer says, “My printer isn’t working, can you fix it?”, a skilled analytical reader knows the customer is not only asking if the company can fix her printer, but also how much it will cost.)

Understand the Author

Adler and Van Doren believe the first step of analytical reading is to understand the author’s goals in writing the book. This requires finding out what problems the author is trying to solve and what questions the book tries to answer. (Shortform note: This task is a bit more complicated for fiction works, as different readers can come away with different understandings of the author’s intent. We’ll learn some more concrete strategies for understanding fictional works in Part 5.)

According to the authors, different categories of books have different typical questions they try to answer. A theoretical book may question whether something is true while a practical book may ask, “What should we do about it?” (Shortform note: Some books may aim to answer both theoretical and practical questions. For example, Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race answers both, “Does systemic racism exist?” and “What should we do about it?”)

Find What the Book Says

In the step above, you figured out what questions the author is trying to answer. Now, Adler and Van Doren argue you need to comprehend what the book is actually saying, and what arguments the author makes in relation to her questions. Well-written books make it easier for the reader to comprehend their arguments using signposts, such as keywords and important sentences. Let’s discuss each in detail.

Keywords

To find what the book says, Adler and Van Doren advise looking for keywords. Keywords are meaningful words or phrases that are used often and convey a wealth of information. As a reader, you need to understand the keywords of the author and what is meant by them. This is especially important because the same word can mean different things to different authors. (Shortform note: Be sure to look for keywords early in the revision process, otherwise you may misunderstand the author’s arguments in the rest of the book. For example, in A Brief History of Time, author and physicist Stephen Hawking uses the word “theory” in a very specific, scientific way, not in the colloquial sense as a simple synonym for the word “idea.” To really understand the rest of the book, it’s crucial to understand how Hawking defines that keyword.)

How do you find keywords? Adler and Van Doren provide two clues to identifying the most important terms in a book. First, a word is probably important if the author deliberately uses it differently than other writers do (particularly if the author makes a point to explain why those other writers’ definitions are incorrect or incomplete). Second, if you struggle to understand how an author is using a particular word, that’s a sign that the word is important: Authors frequently use keywords in unique ways to express their most important (and, often, most complex) ideas.

More Tips on How to Find Keywords

The process of finding keywords in a text can differ based on the type of text and the way you approach it. For example, shorter works like articles often feature keywords in predefined places—such as the first sentence of the article, the last sentence of the first paragraph, and in any repeated phrase throughout the piece.

Additionally, if you already know something about what you’re reading, that can help you identify the keywords. For example, if you’re reading Darwin’s The Origin of Species, you probably know that Darwin’s ideas were part of the theory of evolution, so you’ll know to keep an eye out for “evolution” as a keyword. You can also look for synonyms and related words or phrases, like “heredity” or “survival of the fittest.”

Most Important Sentences

After identifying keywords, Adler and Van Doren recommend finding the author’s leading propositions in her most important sentences. Important sentences express parts of the author’s argument. Here are some tips on how to find them:

- Special sentences may be formatted stylistically or set apart (for example, with italics or underlining).

- The important words are often contained in the important sentences. Therefore, if you spot a keyword, pay special attention to the sentence it’s located in.

- Pay attention to words that confuse you, rather than words that grab your interest. (Shortform note: Remember, the goal of analytical reading is to increase your understanding. It’s perfectly fine to pause at a particularly interesting or entertaining sentence—but if your goal is to better understand the author’s ideas, your time is better spent wrestling with sentences you don’t immediately understand.)

Finding Key Sentences in the Digital Age

In the modern era, there are other, high-tech ways of identifying important sentences that Adler and Van Doren couldn’t imagine in 1972. For example, computer programmers in the field of natural language processing have developed algorithms capable of reading digital text and automatically identifying key terms and sentences. The program is partly based on the frequency of a given word in a text, but it has to distinguish between common-but-not-useful words (like “and” or “the”) and the actual keywords of the text. Once the program identifies the keywords based on frequency, it scans every single sentence and highlights those sentences with higher proportions of keywords—which is essentially a computerized version of the process that Adler and Van Doren recommend.

Identifying Propositions

Adler and Van Doren also advise unpacking complicated sentences to find all the propositions the author is making. For example, in The Body Keeps the Score, author and psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk writes, “No matter how much insight and understanding we develop, the rational brain is basically impotent to talk the emotional brain out of its own reality.” We can break this sentence down into at least five propositions:

- Scientists have developed at least some understanding of this subject.

- There are two parts of the brain: the “rational brain” and the “emotional brain.”

- These two parts of the brain can be in conflict with one another, despite being part of the same physical organ.

- The rational brain may try to override the emotional brain.

- The rational brain cannot overpower or “turn off” the emotional brain when it is activated.

(Shortform note: Not all sentences that appear complex will actually be critical parts of an author’s argument. In some cases, authors may use overly complex language to mask a weak point in their argument. As you read, you’ll need to distinguish between necessary complexity and fluff.)

According to the authors, once you identify a proposition, you should rephrase it in the way most comfortable to you. This is the best way to verify that you understand it. If you can’t restate the author’s idea in your own words, you may have just memorized the words you’ve read rather than truly understood the idea. This can lead to misunderstandings if you encounter the same argument, phrased differently, in another book—you may think you’re reading a brand new idea when you’re really reading another wording of an idea you’ve already read.

(Shortform note: To make sure your new understanding really sinks in, try writing down this restatement by hand rather than just thinking it through in your head or typing it on a keyboard. The physical act of writing things down on paper requires more brain connections than typing (as your brain is processing a more intense sensory experience as well as coordinating fine motor movements), and those extra connections aid your memory and understanding.)

This is especially helpful for comparative reading—different authors say the same thing in different words, and this will help you see how they agree and disagree. (Shortform note: One example of this is the way different authors discuss the racist idea that people of a certain race are genetically superior to people of another race. In Biased, author Jennifer Eberhardt labels this idea “scientific racism”; in How to Be an Antiracist, author Ibram X. Kendi calls the same idea “biological racism.” If you only think to search for one of these terms, you’d miss out on hearing the other author’s thoughts on this idea.)

Sequences of Sentences Form an Argument

According to Adler and Van Doren, until an author supports her principles with reasons, they are merely opinions. You must distinguish between genuine knowledge and mere opinion. (Shortform note: This isn’t always an easy task, especially in the era of “fake news,” in which both opinions and outright falsehoods are sometimes presented as fact. If you’re unsure whether an author is sharing genuine knowledge or merely her own opinion masked as objective fact, consider consulting independent fact-checking organizations, like FactCheck.org or Snopes.)

How to Use External Resources

As much as possible, the authors believe you should struggle with the book independently on a first pass. This will help you see the book’s main arguments, rather than getting mired in minutiae like looking up words you don’t know. Therefore, your job is to first understand the book as well as you can without outside assistance. Once you’ve gotten as far as you can on your own, you can consult external resources to help you.

When you use an external resource, understand 1) what you hope to get from consulting it, and 2) the limitations of the resource. Here is how Adler and Van Doren recommend using external resources, and, where relevant, these sources’ limitations:

Dictionary

- You can use a dictionary to look up words you don’t understand; however, remember that the author may use keywords in atypical ways, which is why you must understand terms from the context of the book.

- Use a dictionary only for the most important words that are critical for understanding.

- (Shortform note: It can be difficult to determine whether a word is important enough to look up in the dictionary. One study suggests looking up words only if they’re used multiple times in the text (not just once) and/or if you’re unable to infer their meaning from context.)

Encyclopedias

- These contain facts and not arguments on subjective questions (“What makes man happy?”), other than what people have said about the subject.

- Use it to resolve disagreements about facts.

- (Shortform note: You may also find encyclopedias (and their online equivalents, like Wikipedia) useful for giving context around an issue or event. For example, if you’re reading Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl, you may want to look up the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands for historical context.)

Summaries/abstracts

- Use these to recover your knowledge about the book after you’ve read it. Do not use these as a substitute for reading the book yourself; the authors believe you’ll develop a bad habit of using these as a crutch, and you’ll get lost understanding a book without a summary. Ideally, you’ve written your own summaries, and you can refer to them when you return to a book.

- According to the authors, there is an exception to this rule: You should use summaries for comparative reading to know if a work will be relevant to your project.

- Note that many summaries have incorrect interpretations or incomplete treatments.

- (Shortform note: The value of a summary depends on your goal as a reader. If you want to understand a particular text in depth, you should read the whole book (multiple times, if necessary). However, if you’re deciding what to read next or simply looking to extract the major ideas from a variety of texts, summaries might be useful.)

Commentaries/reviews

- Like summaries, Adler and Van Doren believe it’s best to avoid these until after your read-through. Otherwise, you’ll start the book biased and focus on things that support the commentary, rather than working to understand what the author is saying.