1-Page Summary

Personal finance can be confusing and overwhelming, but if you focus on taking one small step at a time, you can create a solid financial foundation. Once your finances are under control, you won’t have to worry about money, and you can focus on creating a life you love. The author of I Will Teach You to Be Rich, Ramit Sethi, is a self-taught expert in personal finance. His goal is to help you cut through the noise of conflicting and overly technical financial advice, get past your own hang-ups around money, and take small steps toward a “rich life”—whatever that looks like for you.

In this summary, you’ll learn how to make that “rich life” a reality by using credit cards wisely, choosing the right bank accounts and investment accounts, planning out how you want to spend your money, and ultimately creating a financial system that grows your money automatically.

Credit Cards

If you use credit cards responsibly (by always paying your bill on time, in full), they’re essentially free short-term loans that help improve your credit history, making it easier to get larger loans (like for a mortgage or a car) down the line. Here are the six most important rules for using credit cards the right way:

- Pay your bills on time, preferably in full. Even just one late payment can lower your credit score, raise your annual percentage rate of interest paid (APR), and stick you with a late fee (usually about $35).

- If you’re paying any fees, call your credit card company and get them waived.

- Lower your APR. Ideally, you’re paying off your balance in full every month, but if you’re not able to do that yet, your APR determines how much more you’ll end up paying in total. Calling your credit card company to negotiate a lower APR can save you thousands.

- Keep your accounts open and active. Credit history is an important part of determining your credit score—the longer you keep an account open and continue making on-time payments, the better your score.

- Take advantage of your card’s perks, including automatic extended warranties, airline miles, and rental car insurance.

Paying Off Debt

Getting out of debt not only feels good emotionally, it also boosts your credit score and can save you thousands of dollars in interest. Here’s how to pay off your debt in five steps:

- Step 1: Total up your debt. Many people have no idea how much debt they actually have, which makes it impossible to make a solid plan.

- Step Two: Decide where to start. Focus on fully paying off one card at a time. You can either start with the card with the highest APR or the lowest balance.

- Step 3: Negotiate a lower APR. This will reduce how much you pay in interest.

- Step 4: Figure out how you can afford more aggressive monthly payments. Take a look at your spending habits—where can you afford to cut costs?

- Step 5: Get started. It’s better to get started on a plan that’s mostly solid than to spin your wheels trying to come up with a plan that’s 100% perfect.

Choosing the Best Banks

Together, your credit cards and bank accounts form the foundation of the rest of your financial system. To make sure that foundation is solid, look for accounts with low fees. Fees are how banks make a huge portion of their profits, so low fees are a good sign that a particular bank isn’t trying to squeeze more money out of you for their own benefit.

When you’re looking for a new bank, look for three things:

- Trust. Start by asking your friends which banks they personally trust. Then, browse the websites of those banks. Keep an eye out for excessive fees, minimum required balances, or misleading descriptions of different accounts.

- Convenience. If the bank’s website, app, or other services aren’t convenient to use, you’ll be far less likely to actually use them.

- Features. Make sure the bank offers the basic features you’ll need most: competitive interest rates, free transfers to external accounts, and free bill pay.

Choosing Your Accounts

To start, you’ll need a checking account and a savings account. Here are the ones Sethi personally uses and recommends:

- Schwab Bank Investor Checking with Schwab One Brokerage Account through Charles Schwab Bank. This account boasts an impressive list of features, like zero fees, unlimited ATM fee reimbursements, overdraft protection, and free checks.

- Capital One 360 Savings. Aside from having no fees and no minimums, the main benefit of this account is that you can set up sub-accounts to save up for specific goals (like a wedding or emergency fund).

Investment Accounts

Now that you know how to optimize your credit cards and bank accounts, we’ll turn our focus to opening investment accounts.

The Power of Compounding

Investing is the most powerful way to grow your money because it offers a higher rate of return than even the best savings accounts. On average, the stock market’s annual net return is about 8% (after accounting for inflation). That number is an average from decades worth of data, which means that your money will earn an average of 8% per year over the long-term, even if that rate fluctuates in the short-term.

The reason why that 8% rate is so important is the power of compound interest. With compounding, the interest you earn in a given year is added to the principal (original) amount you invested; then, the following year, you earn interest on that new principal amount.

- For example, let’s say you invest $100 in the stock market (to make things easy, we’ll assume an exact 8% annual rate of return). That means that after one year, you’d have earned $8, for a new total of $108. In the second year, you then earn an 8% return on that new amount, so you’d earn $8.64 for a new total of $116.64. The longer you leave your money in the stock market, the more that principal grows, and the more you earn every year.

The power of compounding also means that the longer you leave your money in the market, the more it grows—which means that the earlier you start investing, the more money you’ll have by the time you retire.

Start by Opening Your 401(k)

A 401(k) is an investment account sponsored by many employers to help their employees save for retirement. When you open a 401(k) account, you authorize your employer to send a certain amount out of each paycheck into that account automatically. A 401(k) is one of the best retirement investment accounts out there for three major reasons:

- The money in your 401(k) is “pretax,” which means it isn’t taxed until you withdraw it. That means your contributions will be much bigger (because they haven’t had taxes taken out of them yet), meaning your principal investment amount is higher, which can increase the compound growth of your investments by 25 to 40%.

- Your employer might match your contribution. That means that every time you funnel money into your 401(k) account, your employer will “match” that contribution up to a certain percentage of your salary. In other words, this is free money.

- You’ll invest automatically, without even knowing it. Your 401(k) contributions come out of your paycheck before you get paid, so you won’t have to worry about investing it yourself—it’s already taken care of by the time you get paid each month.

There is one downside to a 401(k): If you withdraw your money before age 59.5, you’ll incur a 10% early withdrawal penalty in addition to paying income tax on the money. Basically, your 401(k) is exclusively for long-term investing, so you should avoid withdrawing the money early unless you’re absolutely desperate.

Roth IRAs

A Roth IRA is another type of retirement account, but unlike a 401(k), you don’t need an employer to sponsor it. These accounts are only available to people below a certain income level, which changes slightly each year. Roth IRAs also allow you to invest however you want rather than making you choose between a few pre-selected funds like a 401(k).

The other major difference between a Roth IRA and a 401(k) is that the money you invest in your Roth IRA has already been taxed—which means that you’ll pay taxes on the money you put in, but you’ll pay no taxes on the money you earn on top of that. That gives you a huge benefit over a regular, taxable investment account, in which you pay taxes on both your contributions and your returns.

Choosing a Brokerage Firm

To open a Roth IRA, you’ll need an account with an investment brokerage. You should focus on discount brokerages, which offer nearly all the same features as “full service” brokerages, but with much smaller minimum investing fees. (That’s how much money you’ll need before you can actually invest the money in your account. Opening the account itself is always free.) Sethi personally recommends Vanguard, Schwab, and Fidelity as discount brokerages to help you get started investing.

Spending Mindfully

Now that your savings and investment accounts are set up, you need to know how much you can afford to contribute to them every month. To do that, you’ll need a system for spending your money in a way that works for your specific goals, values, and lifestyle. That way, you’ll not only be confident that you’re contributing enough to your savings and investment goals, but you’ll also know that any money left over is yours to spend however you want—with zero guilt.

Deciding How You’ll Spend Your Money

Sethi’s system for mapping out your spending involves dividing your take-home pay into four major areas. The breakdown of these costs should look roughly like this:

- Fixed costs. Fixed monthly costs are your necessities: rent or mortgage payments, groceries, and so on. Add up your total for all monthly costs, then add 15% to cover unexpected expenses like car repair, traffic tickets, or emergency medical treatment. Ideally, your fixed costs should total about 50 to 60% of your monthly take-home pay (the amount on your paycheck after taxes).

- Investments. This category includes contributions to your 401(k), Roth IRA, and any other long-term investment accounts. Investments should be about 10% of your take-home pay.

- Savings goals. This category is for all your savings goals, from short-term (like a vacation) to long-term (like a house). Plan to allot 5 to 10% of your monthly take-home pay for savings.

- Guilt-free spending. Any money you have leftover after accounting for the other categories goes into the guilt-free spending category. This is money you get to use however you like, with zero guilt, because you know you’ve already paid your bills and funded your future through savings and investments. Ideally, this category will have 20-35% of your take-home pay.

Automating Your Financial System

Now that you have a system of spending your money that works for you, it’s time to start automating that plan so that your money divides itself up each month without you having to lift a finger.

How Automation Works

If you’ve ever tried to stick to a budget or keep track of your bills manually, you’ve probably noticed how hard it is to stay on top of your finances when you have to consciously think about where each dollar goes. It’s too easy to get distracted, bored, or overwhelmed, so we end up making costly mistakes. Automation is different: Instead of requiring constant focus, automating your financial system allows you to frontload the hard work by spending a few hours setting up your accounts; after that, you get to move on and focus on other things.

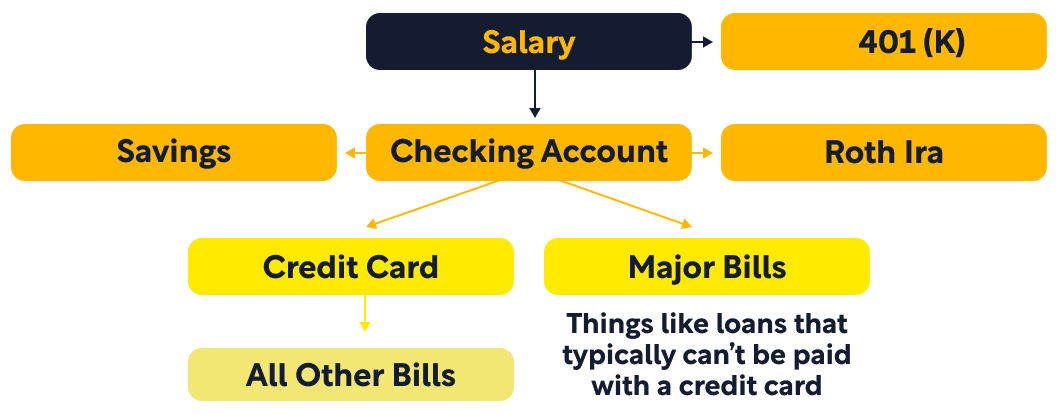

In practice, here’s how automation works: Set up a system of automatic transfers between your checking account, credit cards, bills, savings, and investment accounts. Your checking account will be the central node of this system—once your paycheck lands in that account each month, your system will kick in and initiate transfers from your checking account into all your other accounts based on the percentages you came up with when you mapped your planned expenditure.

Getting Ready to Invest

Now that your pre-planned system of transfers is funneling money into your investment accounts each month, you can start thinking about how to actually invest that money. One crucial thing to note about investing is that funding an investment account is different from actually investing that money. If you set up automatic contributions to your 401(k) and Roth IRA earlier in this summary, you haven’t actually invested that money yet—and it will just sit there, earning zero returns, until you do! This is a common mistake that can cost you thousands of dollars in lost potential returns.

Start your investing journey by learning more about different asset classes, which are the building blocks of investing.

Asset Classes

Asset classes are simply types of investments (like stocks or bonds), and each asset class has varied assets within it. For example, “stocks” is an asset class composed of all kinds of different stocks: large companies, small companies, international companies, and so on. Let’s look at each asset class in more detail, starting with stocks.

Stocks

When you think of investing, you probably think of stocks first. Stocks are shares of ownership in a particular company. Stocks are one of the most unpredictable investments because their value is determined by the shareholders. For example, if a company seems to be doing really well, more and more people will want to buy stock in that company, which drives up the price of each individual share. But if something happens to shake people’s faith in that company (like a merger or a supply shortage), shareholders will start selling off their shares and cause the stock price to drop.

Bonds

Bonds are a different type of asset class. They’re a much more stable investment than stocks because the value of a bond doesn’t fluctuate based on the whims of the market. When you buy a bond, you’re essentially giving a small loan to the bond issuer (which can be the federal government, local governments, or a corporation) with a predetermined payback period. Bonds provide a buffer against market volatility, which means that if some of your investments are in bonds rather than stocks, you won’t lose your entire investment if the market crashes.

Asset Allocation

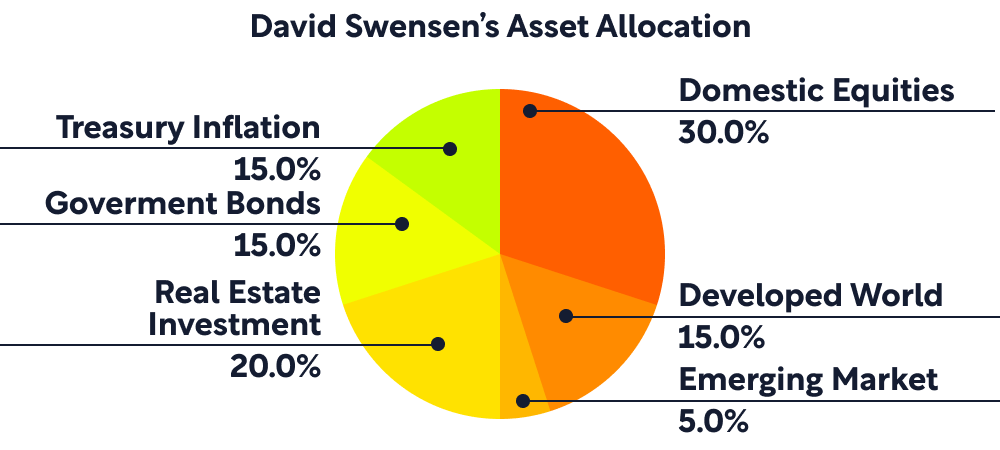

Now that we understand the building blocks of investing, let’s learn how to combine them into a healthy investment portfolio using asset allocation, which is the division of assets (like stocks and bonds) in your portfolio. Managing your asset allocation is the best way to control the amount of risk in your portfolio because you control how much of your money is invested in higher-risk options (like stocks) versus safer investments like bonds. In other words, the way you distribute your investments is more important than the specific stocks, bonds, or funds you choose to invest in.

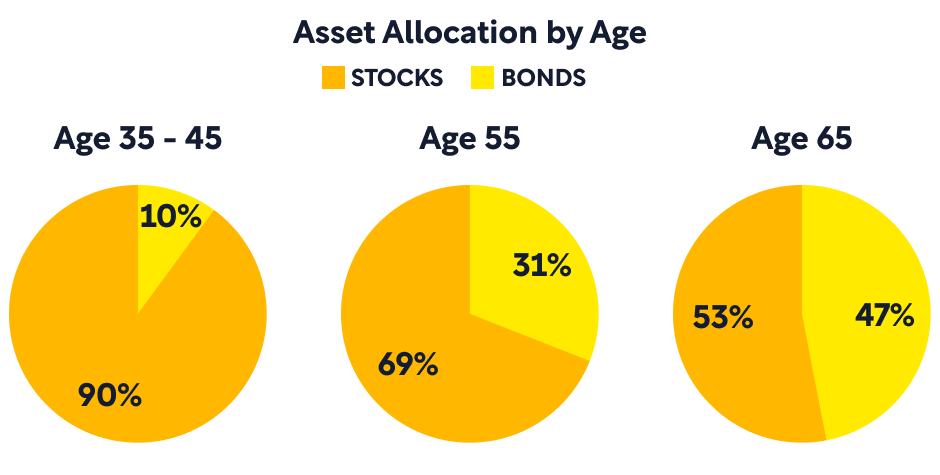

Your asset allocation should reflect your risk tolerance. In your twenties and thirties, you can afford to take bigger risks with your money because you have plenty of time to recover from any losses before you retire. However, as you get older, your risk tolerance will decrease (because if you take a big loss in the stock market at age 59, you won’t necessarily have the time to recoup your investment before retirement). Your asset allocation should change to reflect those changes in your risk tolerance.

Target Date Funds

If keeping track of a portfolio full of stocks, bonds, and index funds makes your head spin, don’t worry. There’s an easier way to invest: Target date funds (also called “target retirement” or “lifecycle” funds), which automatically rebalance your investments based on the year you plan to retire. That way, you don’t have to worry about adjusting your asset allocation as you age—a target date fund will automatically reallocate more of your investments into safer options like bonds as you get closer to retirement. These funds also provide automatic diversification because they’re essentially funds made up of other funds, so you can own stock in a huge variety of companies just by buying into a single target date fund.

Financial Milestones

You may be wondering how your new financial system will fit into the rest of your life. In particular, there are a few financial milestones that most people in their twenties and thirties need to consider—like paying for a wedding, negotiating a salary at a new job, and buying a house.

Paying for a Wedding

Studies show that the average American wedding costs somewhere around $35,000—and that the average American thinks their wedding won’t cost nearly that much. Instead of assuming that you will somehow beat the average and have a truly simple, low-budget wedding, take those statistics to heart and start saving for your wedding now—even if you’re not engaged.

To figure out how much you should be saving each month for your future wedding, start by estimating when you want to get married. Then, use that estimate to figure out how long you have to save, and divide the total wedding cost by that number.

Negotiating a Higher Salary

The best time to negotiate your salary is the moment you get hired because you have more leverage. Here are Sethi’s top tips on how to negotiate a higher salary:

- Make the negotiation about the company, not about you. In other words, emphasize the value you’ll add to the company rather than how much your salary will cost them.

- Leverage other job offers. That way, the hiring manager knows you’re not afraid to walk away if she can’t come up with a fair number.

- Negotiate total compensation, not just money. Don’t be afraid to ask for vacation days or stock options as part of your overall compensation.

- Be friendly. Smile often and remember that your goal is to come up with an agreement that works for both of you.

- Let them make the first offer and don’t reveal your salary. This makes it harder for them to make a lowball offer rather than an offer that reflects the real value of the position.

- Practice, practice, practice. Ask your friends to play the role of hiring manager and drill you with the hardest questions they can think of. You’ll feel awkward at first, but try to take it seriously.

Big-Ticket Purchases

Another financial milestone on the horizon for many young people is buying a car or a house. These “big-ticket” items are important because they’re a unique opportunity to save money.

Buying a Car

The first step to buying a car is figuring out your actual budget. To do this, look back at your plan for expenditure to see how much you can afford to put toward the costs of owning a car every month. This isn’t just a car payment: You also need to include insurance, gas, parking, and maintenance. When you’re deciding what car to buy, keep in mind that the single best way to save money on a car is to drive it for as long as possible, so look for a reliable car and be prepared to invest in preventative maintenance.

When you’re ready to buy, wait until the end of the month, when salespeople are trying to meet their quotas and are more likely to give you a good deal. Then, reach out to a handful of dealerships through their websites, tell them what car you’re looking for, and ask them to quote you a price. You can use those quotes to start a bidding war between the dealerships, which means you get to field lower and lower offers from the comfort of home (you’ll only have to visit the dealership in person at the very end to sign the paperwork).

Buying a House

A house is probably the biggest single purchase you’ll make in your lifetime—and if you come prepared, you can save over $100,000. However, home ownership is often more expensive than people expect. If you own your home, you’ll be responsible for everything a landlord covers when you rent: insurance, property taxes, general upkeep, and fixing anything that goes wrong.

If you do decide to buy, start by deciding on a budget. You’ll need to save up 20% of the price of the home for a down payment. Once you have that saved, total up the total monthly cost of owning a house in your price range (including maintenance, taxes, insurance, and so on). That total monthly cost should be no more than 30% of your monthly income.

Then, do your research to find out the true cost of buying a house. You’ll need to account for closing costs for the sale (typically 2-5% of the price of the house), insurance, property taxes, and any renovations the house needs.

Introduction

Does thinking about your personal finances make your palms start to sweat? If so, you’re not alone. The sheer amount of information out there about managing your finances is overwhelming, especially for people in their 20s or 30s who are just starting their financial journeys. However, if you choose to focus on what you can control instead of giving in to that confusion or focusing on the flaws of our economic system, you can start building the financial habits that will put you on track to a healthy financial life.

The author of I Will Teach You to Be Rich, Ramit Sethi, is a self-taught expert in personal finance. Because he learned the ins and outs of money management through experience, he understands that traditional money advice—like “just stop buying lattes''—is completely unhelpful. His approach is different: Rather than focus on “sexy” strategies like obsessing over the hottest new investment opportunities, Sethi argues that most people just need to know a few basics in order to grow their personal wealth. His goal is to help you cut through the noise of conflicting and overly technical financial advice, get past your own hang-ups around money, and take small steps toward a “rich life”—whatever that looks like for you.

In this chapter, we’ll discuss common excuses people make for not taking control of their financial lives, how to overcome them, and how to define what a “rich life” means to you. Then, in the rest of the summary, we’ll learn how to make that “rich life” a reality by using credit cards wisely, choosing the right bank accounts and investment accounts, planning out how you’ll spend your money, and ultimately creating a financial system that grows your money automatically.

Common Excuses for Not Managing Money (and How to Avoid Them)

As a financial educator, Ramit Sethi has heard every excuse in the book for why his system can’t possibly work for someone because of their individual circumstances. And while there are structural inequalities that give some people an unfair financial advantage over others, the fact that there are some factors you can’t control isn’t a valid excuse for ignoring what you can control.

- For example, if you work at a minimum wage job, it might be much harder for you to save money than it is for someone with a trust fund. And while you can’t change that unfair advantage, you can decide whether to use it as an excuse not to try or to refocus on whatever factor you can control—even if that’s just something as small as automating your credit card payments so you never face another late fee.

Over the years, Sethi has learned that many people don’t want to hear that logic—they’d rather make excuses than take control of the problem. Most of these excuses fall into two categories: decision paralysis and blaming the system.

Decision Paralysis

Information is helpful, but too much information can easily distract and overwhelm us. When people decide to take control of their financial lives, many people feel like they can’t (or shouldn’t) make financial decisions until they have all the information. However, the opposite is true: The more information you have, the less likely you are to act on it. This is called decision paralysis.

Thankfully, all you really need to know are the basics of financial health that you’ll learn in this summary; any information beyond that will just add to the confusion and overwhelm many of us feel when it comes to finances. It’s normal to be nervous about making a mistake, but at this stage in your financial journey, remember that the worst possible mistake you can make is not getting started at all. If you start investing early (ideally before age 35), you’ll be better situated in the long run than someone who waited until age 45 to invest—even if you make a few mistakes along the way.

- If you’re older than 35 and just getting started with investing, don’t let this information scare you off. When it comes to investing, starting early is best, but starting now is far better than not starting at all.

Blaming the System

American socioeconomic policies have created a deeply unequal economic situation in which people who are born into privilege have an unfair advantage over everyone else. While those issues are real and important, they’re outside of anyone’s individual control—so when it comes to growing your own wealth, it’s much more productive to focus on what you can control than to fall back on blaming the system. Here are some of the common excuses people use for giving up on trying to improve their financial lives:

- “My situation means I can’t save.” Your situation may be difficult, and you may not be able to save as much money as other people in the same amount of time, but you can still save some. The important thing is not to use your situation as a reason not to try at all.

- “This financial system won’t work because the society is unfair.” Sometimes, that’s true—the American socioeconomic system is deeply unfair. However, if your goal is to increase your wealth, it doesn’t help to focus on those larger issues that you can’t control. Instead, focus on what you can control; no matter how insignificant it might feel, you’ll always be better off than if you didn’t try.

- “If they’d taught this in school, I’d be better off by now.” If you went to college, they probably did teach personal finance classes, even if you didn’t take them.

- “Financial institutions prey on their customers.” That’s true, and it’s what they’re designed to do. But like any other situation we can’t control, it’s best to move on and focus on the things we can control instead of getting bogged down in anger or helplessness.

- “I can’t afford to get it wrong and end up worse off.” Investing can be scary, especially for people who’ve lived through global economic recessions. However, remember that investing is about long-term wealth—you don’t need to worry about the market fluctuating in the short term so long as there’s even modest long-term growth. If you’re especially nervous, remember that not all investments are equally risky, so you can always put your money in very conservative, low-risk options.

- “I have no way to make extra money to invest.” That’s okay—you don’t need to. Instead of bringing in more money, this book will focus on cutting your existing costs to free up money to invest.

- “I want really impressive returns, not average ones.” When it comes to investing, average is actually the best place to be: You’ll have less risk, avoid unnecessary fees, and still make a solid profit at the average 8% rate of return.

To get the most out of this book, we need to move past these excuses and focus on taking small steps toward financial success. Here are the key ideas to keep in mind as you read:

- “Good enough” is better than perfect. If you can get started with managing your money and get it right most of the time, you’ll still be richer than if you don’t start at all.

- Get comfortable with making mistakes so that you can learn from them.

- Understand your priorities so you can spend money on the things you love—guilt free—by economizing on things that don’t matter to you. The goal of this book is to help you live your version of a rich life, including spending money on whatever means most to you.

- Embrace “boring” when it comes to your financial life. You won’t become a venture capitalist just by following Sethi’s advice, but you’ll consistently grow your money with far less risk.

- The goal of accumulating wealth is to free you up to focus on things other than money. The more hands-off your financial system, the more you can focus on more important things in life than spreadsheets.

- Be proactive with your finances. Instead of passively accepting things like bank fees, make the effort to deal with them now and save yourself thousands in the future.

What Does a “Rich Life” Mean to You?

Being “rich” means something different to everyone. Your version of rich may look like taking lavish vacations every year, or financing your parents’ retirement, or donating huge sums to charity. In any case, having a clear vision of what a rich life means to you will help you define your goals and make financial decisions that will help you get there. We’ll cover specifics later on, but in general, here are Sethi’s 10 rules for a rich life:

- Spend freely on things you love by cutting costs on things you don’t.

- Focus on the five to 10 things that will have the biggest impact on your financial situation instead of getting bogged down in specifics.

- Think of investing as a long-term strategy. You won’t be seeing huge returns right away, but over time, you’ll be better off than people with more “exciting” investments.

- Reducing your spending is helpful, but there’s only so much you can cut. Instead, focus on maximizing your earning potential.

- Ignore financial advice from friends and family. Everybody has conflicting ideas, and getting bogged down in those perspectives will just add to the confusion and decision paralysis.

- Create your own spending rules, including what you will spend on, not just what you won’t. For example, one of Sethi’s personal rules is that if he wants to buy a book, he does—no second guessing, no questions asked. Books are something he allows himself to spend extravagantly on no matter what because he knows he’s cutting the costs in other areas to make that possible.

- Don’t worry about “advanced” tips. Just stick to the basics. You’ll make more progress by consistently focusing on the “boring” rules than wasting time on advanced tips, just like you’ll make more progress as a runner by going for a jog than spending hours comparing different brands of running shoes.

- Focus on what you can control instead of complaining about what you can’t.

- Create the life you really want, not what you think a rich life should be—even if that’s wildly different from other people’s definition of success.

- Do the work now so that your money takes care of itself while you focus on living your best life.

Exercise: Decide What a “Rich Life” Means to You

Being “rich” means something different to everyone. Take a moment to think about what a rich life would look like for you.

In general, what are the most important reasons you want to accumulate wealth? (For example, maybe you want to retire early, have more career flexibility, or eliminate the constant stress of making ends meet.)

Now, list three more specific financial goals by completing the phrase, “I’ll think of myself as rich when I can…” These can be big or small—think anywhere from “order appetizers before a restaurant meal” to “charter my own private yacht”—but try to be as specific as possible. (Remember, these goals should align with your values. They’re less about making money for money’s sake and more about having the freedom to spend time and money on things that are important to you.)

How is your vision of a Rich Life different from what you thought it meant to be “rich” or “successful” growing up? Why is your vision a better fit for you personally than that default definition?

Chapter 1: Credit Cards

Now that you know what a rich life looks like for you, you need to know how to get there. The first step is building healthy credit card habits. You’re probably familiar with the scare tactics other financial writers use to convince you to stay away from credit cards, but credit cards aren’t inherently bad—if you use them responsibly, they’re a great way to proactively improve your credit and get access to useful perks. In this chapter, we’ll learn the pros and cons of credit cards, how to use credit cards responsibly to build your credit, and how to pay off any existing debt you have.

The Pros and Cons of Credit Cards

Credit cards can be a powerful tool in your wealth-building arsenal, but if you already carry credit card debt, you may see them as more of a menace than a tool. The reality is this: If you use credit cards responsibly (by always paying your bill on time, in full), they’re essentially free short-term loans that help improve your credit history , making it easier to get larger loans (like for a mortgage or a car) down the line. On top of that, credit cards offer useful perks, like automatic warranty extensions on purchases you make using the card.

However, if you don’t manage to completely pay off your credit card bills in full every month, the penalties add up quickly. If you only make the minimum payment one month instead of paying off your balance in full, the balance you carry over to the next month starts to rack up interest at the annual percentage rate (APR), which is usually around 14% or higher. That interest keeps accruing as long as you carry a balance, which means that by the time you pay it off, you’ll often have paid more in interest than the original cost of the purchase!

Using Credit Cards to Build Credit

Credit cards are a helpful way to build credit, which is the foundation of the rest of your financial life. Your credit is a snapshot of your debt history, and it’s what lenders use to determine whether to loan you money (like for a mortgage or a student loan). If you use your credit card regularly and pay the balance off in full, you’re essentially taking out a mini loan and paying it back on time every month, which shows lenders that you can be trusted to borrow money and pay it back.

When lenders look at your credit, they’re looking at two main components: your credit report and your credit score. Your credit report is a comprehensive account of your credit history—all the loans and credit cards you’ve ever had, and all the payments you made on them. Your credit score sums up all that information into a single number between 300 and 850—the higher the number, the better your credit and the more attractive you are to lenders. Credit scores are also sometimes called FICO scores because the Fair Isaac Corporation (FICO) invented the credit score system.

A good credit score shows potential lenders that you have a history of paying back your loans, which means there’s less of a risk of them losing money if they give you a loan. As a result, they can offer lower interest rates, which can save you tens of thousands of dollars over the life of the loan. Even if you don’t anticipate needing to apply for a loan in the immediate future, building good credit takes time, and investing that time now will set you up for success years down the line when you do decide to apply for a loan.

To illustrate the importance of having good credit, the table below shows how your credit score changes how much you pay over the life of a 30-year mortgage (based on APRs calculated in 2018). Notice how borrowers with the best credit get the lowest interest rates, meaning they pay significantly less overall than borrowers with poor credit scores. In fact, in this scenario, someone with a score of 620 would pay over $70,000 more than someone with a score of 850 over the life of the mortgage.

| Credit score | APR | Total amount you pay |

| 760-850 | 4.279% | $355,420 |

| 700-759 | 4.501% | $364,856 |

| 680-699 | 4.678% | $372,468 |

| 660-679 | 4.892% | $381,773 |

| 640-659 | 5.322% | $400,804 |

| 620-639 | 5.868% | $425,585 |

Knowing your credit score is important if you want to build wealth. To check your score, you can use a free website like Credit Karma or pay a small fee for a more accurate, official score from MyFico. To get a more comprehensive picture, you can download your entire credit report for free from AnnualCreditReport.com once a year by law. Establishing good credit is one of the most important things you can do to improve your financial situation, so it’s better to focus your energy on that step than worry about cutting costs elsewhere—in the long run, improving your credit will save you much more money than clipping coupons.

Finding the Right Card for You

Using a credit card the right way—by paying off your balance in full every month, on time, using automatic payments—is a fast and easy way to boost your credit. If you’re in the market for a new card, Sethi has four guidelines for choosing the best one for you:

- Opt for a rewards card so that you’ll earn either cash back or travel miles with every dollar you spend on the card.

- Avoid retail store cards. The 10% you’ll save on your purchase at that store won’t make up for the high interest rates and exorbitant fees these cards usually have.

- Stick to two or three credit cards. While credit cards are an important part of your credit history, they’re not the only source of credit—and the more cards you have, the easier it is to slip up, miss a payment, and accidentally damage your credit instead of strengthening it. If you already have a few cards, hold off on opening any new ones for now.

-

Start with Sethi’s personal recommendations.

As a personal finance guru, Sethi’s done his research on the best credit cards out there. Here are the cards he uses personally:

- For everyday purchases: Alliant cash back card

- For travel and eating out: Chase Sapphire Reserve

- For business: Capital One cash back business card

- For extra benefits: Amex Platinum card

Using Credit Cards the Right Way

Once you have credit cards you’re happy with, you need to learn how to use them the right way—otherwise, it’s all too easy to forfeit the benefits and wind up saddled with debts and fees. Here are the six most important rules for using credit cards the right way:

1) Pay your bills on time, preferably in full. Even just one late payment can lower your credit score, raise your APR, and stick you with a late fee (usually about $35). You can bounce back from the occasional hit to your credit, but it’s best to avoid the issue in the first place by setting up automatic payments. If you do miss a payment, call the credit card company and tell them it was a one-time mistake and you’d like to have the late fee removed (make sure you’re telling them you’d like the fee removed, not asking if they can or will remove it). This works more than half the time.

2) If you’re paying any fees, try to get them waived. Start by calling your credit card company and asking a representative whether you’re paying any annual fees or service charges on your card. If you are, tell them you’d like a no-fee account and ask them to waive any current fees. This works more often than you might expect, but if not, ask if they have a no-fee card that you can switch to. Credit card companies don’t want to lose your business, so they’ll work with you to find a solution.

3) Lower your APR. Again, this involves calling your credit card company. If you’re nervous about the idea of negotiating, keep in mind that credit card APRs are usually between 13-16% and can be much higher. Ideally, you’re paying off your balance in full every month, but if you’re not able to do that yet, your APR determines how much more you’ll end up paying in total.

- To make that more concrete: Let’s say you buy a $1000 smartphone on a card with a 14% APR. If you only make the minimum payments each month instead of paying off the balance in full, you’ll end up paying $732.76 in interest by the time you pay off the phone—so that $1000 phone ends up actually costing you $1732.76. You might occasionally need to use your credit card for a legitimate need that you can’t pay off right away, so lowering the APR as much as possible is crucial to limiting how much extra you’ll end up paying for that purchase.

- When you call, tell the representative that you want a lower APR. When they ask why, use one of two reasons: If you have no debt, tell them you’ve been paying your bill in full and on time for several months now. If you do have debt, tell them you want to begin paying it down more aggressively. In either case, make sure to mention that other cards are offering lower APRs , and that you don’t want to have to switch your business to a different company that offers a low-interest card. Offering you a discount is often cheaper for the company than having to sign a brand new customer, so they may work with you if it means keeping your business.

4) Keep your accounts open and active. Credit history is an important part of determining your credit score—the longer you keep an account open and continue making on-time payments, the better your score. That means that keeping that account open will ultimately benefit you more than switching your main card every time you find a great introductory APR somewhere else. This is especially important if you’re planning to apply for a loan in the next six months because closing an account will slightly reduce your credit score.

5) Call your credit card company and get a credit increase—but only if you have no current debt. This improves your credit utilization rate , which is responsible for determining 30% of your credit score. Your credit utilization rate is how much of your available credit you’ve actually used, which we can calculate by dividing the balance you currently owe by your total available credit.

- For example, if you owe $1,000 and have $1,000 in available credit, you’ve used 100% of your available credit. But if you owe $1,000 and have $5,000 in available credit, you’ve only used 20% of the total available credit. The lower your credit utilization rate, the better your credit score, because you’re less at risk of defaulting on the card.

- You should only use this tip if you have no existing credit card debt because increasing your credit limit could tempt you to spend more and ultimately accumulate more debt rather than help you pay it down.

6) Take advantage of your card’s perks. If you have a rewards card, you probably know that you can earn cash back and airline miles on your purchases. However, credit cards offer a host of other benefits, such as:

- Automatically extending the warranty on anything you purchase on the card (meaning that even when the manufacturer warranty expires, you can still get repairs and replacements covered)

- Trip insurance to reimburse airline change fees

- Rental car insurance for damages up to $50,000

- Concierge services that can help you get tickets to sold-out events

- Disputing charges on your behalf (for example, if your cell phone company charges you a fee even after you’ve negotiated out of it, your credit card company can often get the fee reimbursed for you)

Credit Card Debt

Most people have at least some debt, whether from credit cards, student loans, or a mortgage. In this chapter, we’ll discuss credit card debt exclusively (we’ll cover student loan debt in Chapter 7). Although we think of it as “normal,” debt can be a crushing weight, both financially and emotionally. Those emotions are so overwhelming that we freeze up and avoid thinking about debt at all costs instead of actively working to pay it down.

To justify ignoring the problem, we fall back on a host of invisible money scripts . This is a term coined by financial psychologist Dr. Brad Klontz to describe the unconscious beliefs we absorb in childhood about money and debt that end up influencing our financial behavior as adults. Here are the types of invisible scripts people have around credit card debt and what they sound like in practice:

- Comparing ourselves to others. “Everyone has credit card debt. At least I don’t have as much as my friends do.”

- Using the size of the problem as an excuse not to try at all. “It doesn’t matter how much I spend now—I have so much debt that I’ll never be able to pay it off, anyway.”

- Normalizing the problem. “I already pay other fees, so I don’t mind paying interest.”

- Not taking personal responsibility. “Credit card companies are predatory. It’s their fault that I’m in debt.”

- Ignoring the problem. “I don’t even know how much debt I have.”

- Giving in to hopelessness. “I’m doing my best.”

When we rely on these invisible scripts, we give up the power to do something about debt. Becoming aware of these scripts is the first step to taking that power back; the next step is taking responsibility for the problem and the solution. Once you accept that you can do something about the problem, you can make a plan to attack your debt as aggressively as possible. Having a plan turns a scary, overwhelming, emotional topic like debt into a simple, manageable math problem.

Paying Off Debt

Getting out of debt not only feels good emotionally, but it also boosts your credit score and can save you thousands of dollars in interest. Instead of thinking of debt as a looming monster you’ll have to deal with “someday,” think about how much money you’re losing every day by carrying a balance that’s racking up interest. To illustrate this, imagine you have $5,000 in credit card debt at 14% APR. You could approach this in a few different ways.

- You could pay only the monthly minimum (usually 2% of your balance). In this case, your first payment would be $100 (2% of $5,000). However, because the payment is a percentage of the balance, it will decrease as your balance decreases (so when your balance gets down to $4,000, your payment will go down to $80 per month). With this strategy, you’re making smaller and smaller payments each month, which stretches out the repayment period for years.

- Alternatively, you could pay a fixed amount each month—let’s say $100. This starts out the same as the situation above, but because it’s a fixed amount and not a variable percentage, you’re paying the balance down more aggressively as time goes on, not less. At the start, you’ll pay $100, which is 2% of your $5,000 balance; when your balance gets down to $4,000, you’ll still pay $100, which is now 2.5% of the balance. By the time your balance is $1,000, your fixed payments will be a full 10% of the balance.

To see how much time and interest money you’d save by paying more than the monthly minimum on that $5,000 debt at 14% APR, look at the chart below. Notice how doubling your fixed monthly payment from $100 to $200 would save you roughly four years of payments and $1,600 in interest.

| Monthly payment | Years to fully pay off | Total interest paid |

| $100 (variable monthly minimum) | 25 years | $6,322.22 |

| $100 (fixed payment) | 6.3 years | $2,547.85 |

| $200 (fixed payment) | 2.5 years | $946.20 |

Five Steps to Paying Off Debt

It’s time to get proactive about paying off debt. This process can take time, but with every payment, you’ll have the satisfaction of knowing you’re actually doing something about your debt. Remember, little steps can add up to big financial wins.

Step 1: Total up your debt. Many people have no idea how much debt they actually have, which makes it impossible to make a solid plan (because the process of paying off $1,000 of debt might look a lot different than paying off $12,000). To get a sense of your current situation, call your credit card companies using the phone number on the back of your cards and find out your total debt, the APR, and current minimum monthly payment. Keep track of all the information using a chart like this one:

| Card name | Total debt | APR | Minimum payment |

| Card 1 | $1000 | 14% | $20 |

| Card 2 | $2000 | 18% | $40 |

Step Two: Decide where to start. You’ll want to focus on fully paying off one card at a time instead of increasing your payments on all of them. You can do this in two ways:

- Start with the highest APR (in the chart above, that’s Card 2). This is the most financially efficient way to pay off debt because the card with the highest APR is costing you the most in interest for each month you stay in debt.

- Start with the lowest balance (in the chart above, that’s Card 1). This is financial guru Dave Ramsey’s “snowball method.” It’s slightly less efficient in terms of pure financial math, but it has the psychological advantage: If you start with the lowest balance, you should be able to pay it off pretty quickly, and paying off an entire card’s debt is a huge win that will motivate you to keep going.

These are both solid options for paying off debt, so don’t get hung up on choosing where to start—pick one, commit to it, and move on. Remember, getting started on paying off debt is more important than doing it perfectly.

Step 3: Negotiate a lower APR. This is something everyone should be doing, whether or not they have credit card debt. Remember, the key is to let the credit card representative know that other cards are offering lower APRs, and you’d hate to have to transfer your balance to another company with a better interest rate. Credit card companies want to keep your business—use this to your advantage.

Step 4: Figure out how you can afford more aggressive monthly payments. You don’t necessarily need to bring in more money every month, you just need to reprioritize and divert money that you’re already spending elsewhere into your debt. Take a look at your spending habits—where can you afford to cut costs? If you’re not sure, keep that question in mind as you read the rest of this summary—you’ll find tips for saving money that you can use toward paying down your debts. Remember, the financial and emotional benefits of paying off debt will be worth any temporary sacrifices you make.

- There are other, less effective ways to fund your debt payoff—namely, balance transfers (essentially, using a credit card with a lower APR to pay off the current debt on a card with a higher APR) and taking money from your 401(k) or home equity line of credit (HELOC). Sethi cautions against these methods because they don’t address the root problem of your spending behavior. Instead, focus on building good financial habits by reducing spending and prioritizing building credit by getting out of debt.

Step 5: Get started. Remember that it’s better to get started on a plan that’s good enough than to spin your wheels trying to come up with a plan that’s 100% perfect.

Credit Card Action Items

Now that you’re a credit card expert, it’s time to apply that knowledge. Here are your concrete action steps to make your credit cards work for you:

- Log onto your credit card’s website and set up automatic payments. That way, you’ll pay on time every month without having to worry about it at all. Each month, you’ll get a statement before the automatic payment goes through, so if you don’t have enough in your checking account to make your usual payment that month, you can log in and change the amount of the scheduled payment.

-

Call your credit card company

(you’ll find their phone number on the back of your card). Ask them to:

- Waive the fees on your card

- Lower your APR

- Send you a list of all their available perks

- Use your main credit cards to set up automatic payments on your other bills. For example, if you set up autopay on a streaming service using one of your credit cards, that card automatically stays active and continues building a solid payment history—and because you’ve already set it up so your checking account automatically pays your credit card balance every month, you can reap the benefits of using a credit card without any worry about missing payments.

- Make a plan to pay off your debt. When it comes to debt, half the battle is accepting the situation and actually taking action instead of ignoring it and hoping it’ll go away. Figure out how much you owe and make a plan for how to pay it down more aggressively (you can use financial calculators online to see how your repayment date and the total amount paid will change depending on how much you increase your monthly payments). Then, set up automatic payments so you can attack your debt without having to think about it each month.

Chapter 2: Bank Accounts

Now that you have your credit cards set up, it’s time to choose the right bank accounts to back them up. Together, your credit cards and bank accounts form the foundation of the rest of your financial system. Taking a little bit of time to set up the right accounts now will save you time, money, and frustration down the line. In this chapter, we’ll learn how banks make money off their customers and how to tell the difference between trustworthy banks and predatory ones. Then, we’ll discuss the best checking and savings accounts, including the ones Sethi uses personally. Finally, we’ll learn how to optimize your accounts to avoid fees and earn more interest.

Choosing the Best Banks

What makes a “good” bank? Low fees are an important component. Fees are how banks make a huge portion of their profits—in 2017, banks made a cool $34 billion from overdraft fees alone—so low fees are a good sign that a particular bank isn’t trying to squeeze more money out of you for their own benefit. For example, Bank of America has a reputation for exorbitant fees on every kind of account (and has even taken customers to court over fees that the bank mistakenly levied).

In addition to fees, a bank’s history and reputation are important. Whether you’re evaluating your existing bank accounts or searching for a new one, keep in mind that banks are businesses, and some have a better customer service track record than others. Before you choose where to keep your money, look at each bank’s history: Do they charge ludicrous fees or push unnecessary products? Even worse, have they ever been accused of fraud? If so, you can assume that pattern will continue, and you’re much better off choosing a bank with a better reputation.

- For example, federal regulators fined Wells Fargo $1 billion after they admitted to opening unauthorized accounts for 3.5 million people as well as forcing 570,000 customers to buy auto insurance that they didn’t need. Even worse, 20,000 of those customers ultimately had their cars repossessed because of Wells Fargo’s predatory tactics.

On the other hand, some banks have a solid reputation for honesty and integrity. These companies put their clients first and focus on customer service rather than relying on exorbitant fees to make their money. Schwab and Vanguard both meet these high standards—they offer low fees, solid benefits, and don’t push unnecessary products—which is why Sethi personally uses and recommends them. When you’re looking for a new bank, look for three things:

- Trust. While major scandals like Wells Fargo’s are rare, you should still do your research before deciding which banks to trust. Start by asking your friends which banks they personally trust. Then, browse the websites of those banks. Keep an eye out for excessive fees, minimum required balances, or misleading descriptions of different accounts. Make sure their customer service department is available 24/7 in case you run into trouble.

- Convenience. If the bank’s website, app, or other services aren’t convenient to use, you’ll be far less likely to actually use them. The goal here is to set up a financial system that will eventually run itself, so you want to start with bank accounts that are as convenient as possible.

- Features. Make sure the bank offers the basic features you’ll need most: competitive interest rates, free transfers to external accounts, and free bill pay. Keep in mind your own deposit needs, too: If you deposit cash often, you’ll need a bank with a local physical location. If you deposit checks often, you’ll probably want a bank that allows mobile check deposits through their app.

- One important caveat: Competitive interest rates are important, but if you spot a higher rate at a different bank after you’ve set up accounts you’re generally happy with, don’t switch accounts to chase those high interest rates. Those offers are often introductory and expire within a few months, so you’ll waste a lot of time chasing a boost of just a few dollars in interest. In terms of financial gains, you’ll be much better off using that time to set up investment accounts instead (as we’ll discuss in Chapter 3).

Switching Banks

If you already have an account with Bank of America or Wells Fargo, or you do some digging and discover that your current bank is charging you excessive fees or has a pattern of bad behavior, it’s time to switch.

For many people, the idea of opening a new bank account, transferring money, and closing the old one is so daunting that they give up and stay with their existing bank, even if it’s a terrible one. However, banks are such a fundamental part of your financial system that even if there are just a few minor issues with your current bank (like a fee they refuse to waive), those minor annoyances can become major problems once your net worth increases. You’re far better off investing one afternoon now to set up a solid foundation that will save you headaches for decades to come.

Choosing Your Accounts

Now that you know which banks to avoid entirely, let’s focus on the specific types of accounts you’ll need to open: a checking account and a savings account.

Checking accounts are set up to make withdrawing money easy, whether from an ATM or through transfers to other accounts. It’s also the account where your paycheck will land first before being split up into savings, investments, and spending money.

Savings accounts, on the other hand, aren’t designed for frequent withdrawals. You’ll use your savings account to save up for short- to mid-term goals (like a trip or an emergency fund)—once you deposit money into that account, you likely won’t withdraw it until you’ve met your full savings goal.

Another benefit to using a dedicated account for your savings goals (instead of just keeping that money in your checking account) is that it’s much less tempting to dip into that money for other things. For example, if you’re saving up for a car and you keep that money in a savings account at a different bank than your checking account, it will be so inconvenient to have to transfer the money between banks that you’ll think twice before borrowing from that account for a shopping spree (and derailing your savings goal in the process).

Precisely how you set up your checking and savings accounts depends on your personality and how hands-on you want to be with managing your money. There are three possible setups:

- A checking account and a savings account at the same local bank. This is the most basic option. If this is the setup you have now and you decide to stick with it, make sure to double check that you’re not paying any fees on either account. (Technically, you could use a credit union, too, but Sethi doesn’t recommend them—their customer-owned structure is a fantastic alternative to predatory big banks, but their services often just can’t measure up to the features that larger banks offer).

- A local bank checking account and an online savings account. For most people, this is the best option. It’s the best of both worlds—you have the convenience of a local bank for your checking account (which is especially important if you need to make cash deposits), plus the higher interest rates that online savings accounts offer.

- Multiple checkings and savings accounts at multiple banks. This option offers the most customization, but it’s also the most confusing. However, if you’re someone who loves personal finance and wants to find the best possible interest rates, the added confusion of having multiple accounts might be worth it.

Once you decide on which setup works for you, it’s time to find the exact accounts you’ll use. In the following two sections, you’ll see the checking and savings accounts that Sethi recommends, as well as the accounts he uses personally.

Checking Accounts

Your checking account is one of the most important components of your financial system because it’s the first place your money lands before it gets sent off to your credit card, bills, savings, and investments each month. Later on in this summary, you’ll learn how to set up automatic transfers for all of those, so you won’t have to worry about your checking account very often—it just needs to be a solid, fee-free first step in your financial system.

The Best Checking Accounts

- Schwab Bank Investor Checking with Schwab One Brokerage Account through Charles Schwab Bank. Sethi uses this account personally and considers it the best on the market. This account boasts an impressive list of features, like zero fees, unlimited ATM fee reimbursements, overdraft protection, and free checks.

- The Investor Checking account is unique in that it’s linked to a brokerage (investment) account. That means you’ll have to open a Schwab brokerage account in order to access all the benefits of their checking account—but you don’t actually have to use the brokerage account in order to get those benefits (and don’t worry, you won’t be charged any fees for leaving the brokerage account empty and inactive).

- A no fee, no minimum account at your local bank. This is especially helpful if you need to deposit cash frequently (you can’t make cash deposits into the Schwab Investor Checking account). Keep in mind that you may have to set up direct deposit in order to have fees waived at local banks. (If you’re a college student, ask about student accounts. These are typically barebones accounts that offer zero fees and few fancy add-on services.)

Savings Accounts

Your savings account is where you’ll save up for short- and mid-term savings goals, up to five years away (for longer-term savings goals, you’ll use your investment accounts, which we’ll cover later in this summary). The main benefit to keeping this money in a savings account rather than simply in your checking account is that savings accounts have higher interest rates, so your money will be able to grow while you save. However, those interest rates are still rarely high enough to make a huge difference.

- For example, if you have $5,000 in a savings account that offers a 0.5% interest rate, you'll earn $25 per year in interest. If you have that same $5,000 in an account with a 3% interest rate, you’ll earn $150 per year in interest. Earning that extra $125 per year is helpful, certainly—but because the bulk of your money will be in investment accounts that earn an average of 8% each year, that extra $125 doesn’t actually make that big a difference in your overall wealth (especially when you take inflation into account, which can often make the interest you accrue worth even less as the value of a dollar changes).

As you research savings accounts, stick to online banks rather than “Big Banks” with physical locations. You’ll earn more interest and face fewer hurdles to getting your account up and running.

The Best Savings Accounts

- Capital One 360 Savings. This is the savings account Sethi uses personally. Aside from having no fees and no minimums, the main benefit of this account is that you can set up sub-accounts to save up for specific goals (like a wedding or emergency fund).

- Other savings accounts that have no fees, no minimums, and the ability to set up sub-accounts include:

- Ally Online Savings Account

- Marcus by Goldman Sachs

- American Express Personal Savings

Negotiating Bank Fees

If you prefer to stay at your current bank, make sure you’re not paying any fees. Even a small monthly maintenance fee is often enough to totally negate any interest you earn on your account. Even worse, things like overdraft fees can add up quickly, turning a $5 overdraft into a $100 mistake. Negotiating those fees might seem intimidating, but the savings add up in the long run.

Negotiating General Account Fees

If your account does have fees, call your bank and try to get them waived. In some cases, banks might be willing to waive fees if you set up direct deposit. If not (or if your job doesn’t offer direct deposit), you’ll have to negotiate. Here’s how:

- Call the bank’s customer service number. Tell them you’ve noticed your account has fees and that you’d like to change to an account with no fees and no minimum balance.

- If they say they don’t offer that kind of account, don’t give up! Tell them you’ve seen their competitors offer that exact deal and ask them to check again for any no-fee accounts they can offer (make sure to cite a specific competitor and a real offer). Often, this is all it takes for them to suddenly be willing to waive all fees.

- If the first two steps don’t work, ask to speak to a supervisor, then repeat your first arguments. If they still won’t budge, tell them you’ve been a loyal customer for a long time (specify how many years), that you know they’ve already invested hundreds of dollars to land you as a customer, and that you’d hate to have to take your business elsewhere.

Negotiating a Specific Fee

If you’re facing an existing overdraft fee, late fee, or processing fee, try calling up your bank and asking them to waive it. If it’s your first time being charged that fee (or if you have a good excuse, like overdrawing because your automatic transfer posted a day late), most banks will happily waive the fee. Here’s now to handle this negotiation:

- Call the bank, reference the specific fee on your account, and ask them to waive it.

- If they refuse, don’t give up! They’re counting on you to take their first answer and walk away. Instead, repeat the issue and ask them what they can do to help (this works about 85% of the time).

- If that doesn’t work, remind them that you’ve been a loyal customer for several years and that you’d prefer to stay with them rather than go through the headache of switching to one of their competitors. Most of the time, the customer service representative will talk to their supervisor and ultimately waive your fee.

Bank Account Action Items

Now that you have a solid understanding of how to find the best bank accounts, here are your action steps:

- Find a checking account that works for you and open a new account. If you decide to stick with your current checking account, call your bank to make sure your account has zero fees or minimums. If you do have fees, negotiate your way into a no-fee account (and don’t be afraid to take your business elsewhere if your bank doesn’t play along).

- Open a high-interest savings account at an online bank. This should be an entirely separate bank from your checking account—that way, it’ll be much less convenient to dip into your savings on a whim (because transferring money between banks takes longer than transferring money between two accounts at the same bank).

- Transfer your money into your new savings account. Be sure to leave enough in your old account to cover one and a half months of living expenses. This gives you time to switch your bill payments over to the new account and avoid accidental overdrafts if one of them tries to charge your old, empty account.

Chapter 3: Opening Your Investment Accounts

By now, you’ve optimized your credit cards and bank accounts and created a solid foundation for the rest of your financial system. Next, we’ll turn our focus to opening investment accounts. Investing is the best way to grow your money into more money, and starting early is crucial to maximizing that growth.

In this chapter, we’ll see why investing is such a powerful tool to grow your wealth and why starting to invest at a young age makes such a difference. We’ll also examine why so many young people miss out on those returns by not investing. Then, we’ll go through the initial steps of investing, which will help demystify investments and give you concrete action items to help you get started. Finally, we’ll cover the main types of investment accounts you should consider—401(k)s, Roth IRAs, and Health Savings Accounts (HSAs)—as well as how to choose a brokerage firm to help you open and fund those accounts.

The Power of Compounding

Investing is the most powerful way to grow your money because it offers a higher rate of return than even the best savings accounts. On average, the stock market’s annual net return is about 8% (after accounting for inflation). That number is an average from decades worth of data, which means that your money will earn an average of 8% per year over the long-term, even if that rate fluctuates in the short-term.

The reason why that 8% rate is so important is the power of compound interest. With compounding, the interest you earn in a given year is added to the principal (original) amount you invested; then, the following year, you earn interest on that new principal amount.

- For example, let’s say you invest $100 in the stock market (to make things easy, we’ll assume an exact 8% annual rate of return). That means that after one year, you’d have earned $8, for a new total of $108. In the second year, you then earn an 8% return on that new amount, so you’d earn $8.64 for a new total of $116.64. The longer you leave your money in the stock market, the more that principal grows, and the more you earn every year.

Compounding maximizes returns on a one-time investment—but if you keep investing more money at regular intervals, those returns grow exponentially. The more you add, the more your principal grows, which creates a higher total for you to earn an 8% return on. In the table below, you can see the difference after 10 years of investing $10 per week compared to investing $50 per week.

| Amount invested per week | Total after 1 year | Total after 5 years | Total after 10 years |

| $10 | $541 | $3,173 | $7,836 |

| $20 | $1,082 | $6,347 | $15,672 |

| $50 | $2,705 | $15,867 | $39,181 |

The Importance of Starting Young

The power of compounding also means that the longer you leave your money in the market, the more it grows—which means that the earlier you start investing, the more money you’ll have by the time you retire. To see this in action, consider two fictional people who both decide to invest $200 every month.

- Sally starts investing at age 35 and keeps actively contributing to her accounts for 10 years (after that, she lets her money grow without actively adding more to it). By the time she’s 65, her accounts will be worth $181,469 (assuming an 8% rate of return).

- Dan, on the other hand, doesn’t start investing until he’s 45, but he keeps it up for 20 years. By the time he’s 65, Dan’s accounts will be worth $118,589— that’s $60,000 less than Sally, even though Dan invested for twice as long!

(However, this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t start investing if you’re already in your 40s. Your money will still grow—maybe not as much as it would have if you’d started 10 years ago, but far more than it will if you never get started at all!)

Invisible Investment Scripts

As we’ve seen, if you start investing when you’re young, you’ll earn tens or even hundreds of thousands more over the course of your lifetime than someone who starts investing later. So why aren’t more young people investing? The answer has to do with the invisible scripts we all have about investing. Here are some examples of invisible scripts and Sethi’s responses to them:

- “There’s too much information. I’m overwhelmed.” Remember that you don’t have to be perfect, you just have to get started. Pick one source of information to start with and go from there.

- “I don’t know how to time the market.” You don’t have to. Just invest a little bit every week, regardless of what the market’s doing, and you’ll come out on top in the long run.

- “Investing in stocks means giving up control of my money.” It might seem counterintuitive, but this is a good thing. Studies show that consistent, automated investing leads to greater returns than if you try to buy, sell, and trade on your own.

- “I don’t know enough to do it right, so I’m better off doing nothing.” Not only are you losing out on the opportunity to grow your money, but doing nothing will actually lose you money in the long run because of inflation.

- “The fees are too high.” The fees are only high if you’re actively trading stocks, which you won’t be if you follow Sethi’s advice to automate your investments.

- “I don’t make enough money.” It’s hard to think about investing when you’re living paycheck to paycheck, but if you sit down and look at your spending habits, you’ll more than likely find a place where you can cut $10 per week to invest instead.

All of these invisible scripts about investing usually have the same outcome: People put off thinking seriously about their finances until their 40s, when they suddenly realize they might not have enough money for retirement. Starting earlier—even if you’re not an expert—will save you years of worry down the line.

The Steps of Starting to Invest

Now that we’ve seen what a powerful tool investing is for growing your personal wealth and confronted some of the common reasons people don’t invest, it’s time to make a plan for how to get started. To do that, we’ll use a six-step process for getting started with investing:

- Step 1: Take advantage of your employer’s 401(k) match.

- Step 2: Get rid of credit card debt

- Step 3: Open a Roth IRA.

- Step 4: Max out your 401(k).

- Step 5: Find out if you’re eligible for an HSA.

- Step 6: Open a regular taxable investment account and fund it.

In the next sections, we’ll cover the 401(k), Roth IRA, and HSA accounts in more depth. As you read, keep in mind that investing through these accounts requires two steps: funding the account and actually investing the money in it . Many people end up not investing at all because they mistakenly assume their money is automatically invested once they set up automatic transfers into their 401(k) or Roth IRA. That can be a costly mistake: If you pour money into your account but never actually invest it, it will just sit there without earning any returns. In this chapter, we’re only going to focus on opening the accounts and funding them—we’ll get to the actual investing in Chapter 7.

Start With Your 401(k)

A 401(k) is an investment account sponsored by many employers to help their employees save for retirement. When you open a 401(k) account, you authorize your employer to send a certain amount out of each paycheck into that account automatically. The money in your 401(k) isn’t automatically invested—you’ll have to actively decide where to invest it (we’ll cover that in detail in Chapter 7). A 401(k) is one of the best retirement investment accounts out there for three major reasons.

1. The money in your 401(k) is “pretax,” which means it isn’t taxed until you withdraw it. That means your contributions will be much bigger (because they haven’t had taxes taken out of them yet), meaning your principal investment amount is higher, which can increase the compound growth of your investments by 25 to 40%. You’ll have to pay taxes on the money when you withdraw it, but because of compound interest, you’ll still come out ahead compared to a regular investment account (where you invest money that has already been taxed).

2. Your employer might match your contribution. That means that every time you funnel money into your 401(k) account, your employer will “match” that contribution up to a certain percentage of your salary. For example, if your employer has a one-to-one matching policy up to 5% of your salary, that means that if you contribute 5% of your salary, your employer will double that contribution. In other words, this is free money . To see how big a difference this makes, look at the table below to see how a 401(k) account grows over time, with and without matching (assuming 8% returns).

| Age | Account balance without matching | Account balance with matching |

| 35 | $3,240 | $6,480 |

| 40 | $19,007 | $38,016 |

| 45 | $46,936 | $93,873 |

| 50 | $87,973 | $175,946 |

| 55 | $148,269 | $296,538 |

| 60 | $236,863 | $473,726 |

| 65 | $367,038 | $734,075 |

3. You’ll invest automatically, without even knowing it. Your 401(k) contributions come out of your paycheck before you get paid, so you won’t have to worry about investing it yourself—it’s already taken care of by the time you get paid each month.

There is one downside to a 401(k): If you withdraw your money before age 59.5, you’ll incur a 10% early withdrawal penalty in addition to paying income tax on the money. Basically, your 401(k) is exclusively for long-term investing, so you should avoid withdrawing the money early unless you’re absolutely desperate.

(If your employer doesn’t offer a 401(k), don’t worry! In the next section we’ll learn how to set up a Roth IRA, which is a different type of tax-advantaged retirement account open to everyone below a certain income level. And if you’re self-employed, look into Solo 401(k) and SEP-IRA accounts, which function similarly to a traditional 401(k) for people who don’t work for a traditional employer.)

If You Change Jobs

If you get a new job, you won’t lose your 401(k) money—but because the account itself is sponsored by your old employer, you’ll have to move that money somewhere else. There are a few different ways to do this:

- The best option is to “roll over” the money from your 401(k) into an IRA . Once the money is in an IRA, you’ll have more control over where to invest it (because 401(k) investment options are usually very limited). A brokerage firm can help you transfer the money into an IRA for free.

- You could also roll the money in your existing 401(k) over to your new company’s 401(k) . The problem with this is that if you use that money to fund your new 401(k), those contributions won’t be eligible for employer match, so you lose out on the main benefits of a 401(k).

- You could leave your 401(k) where it is . This is dangerous—it’s easy to forget about an old 401(k) and end up letting your money stagnate.

- Finally, you could cash the money out and pay the hefty early-withdrawal penalties—but you’ll lose a lot of money this way!

Roth IRAs