1-Page Summary

Standard economic theory relies on the idea that humans use infallible logic when making decisions, and even when we make wrong decisions, we quickly realize and remedy them. On the other hand, behavioral economics argues that humans frequently act irrationally, and we often don’t realize our errors at all. Instead, we continue making the same mistakes—we’re not only irrational but predictably so.

The good news is, it doesn’t need to be this way—here, we’ll discuss common pitfalls of human logic, and explore the forces that really drive your actions. Armed with this knowledge and awareness, you can consciously avoid the triggers of irrationality and improve your decision-making skills.

Irrationality Trigger #1: Relativity

It’s human nature to make comparisons to find guidance toward the “right” choice. We don’t have an inherent sense of the value of things, so we resort to surmising the value of an item by considering its relative advantage or disadvantage over another. Because of our need for guidance, relativity has a powerful influence on how we make decisions.

Many advertisers play into this need using the decoy effect. That is, they present you with options, including a clearly unfavorable option—the “decoy”—to trigger a comparison that will guide you toward a specific choice.

- For example, an advertisement for magazine subscription bundles might include three options: internet only for $59/year; print only for $125/year; and an internet and print bundle for $125/year. You’ll likely conclude that the print-only option—the decoy—is a rip-off. It’s much more expensive than the internet option, even though both options include only one medium. Instead, you’ll choose the bundle, which appears to offer two media for the price of one. However, if the print-only option weren’t included, you’d likely choose the cheapest option, internet-only.

We compound the decoy effect by making irrational comparisons—we tend to focus on similar, easily comparable products and reject products that are different and thus less easily comparable.

- Salespeople know this and play into it. When you’re deciding between two options (A and B) and their accompanying attributes, you’ll likely be presented with a decoy third option (-A). This option is similar to—but worse than—one of the options. Because the two “A” options are more easily comparable than A and B, you’ll quickly reject option B. Then, because the -A option is clearly worse than the A option, A will be your final decision—just as the salesperson intended.

Relativity doesn’t just drive irrational decision-making—it makes us miserable. We measure our possessions against others’ due to our comparative nature, which leads us into a trap of comparative consumption. There are two ways to avoid this trap.

- First, you can diminish your comparison opportunities. By controlling what products you see, you can exercise control over how tempted you are to make comparisons. For example, if you’re car shopping, only look at options within your means instead of browsing expensive, unwise choices.

- Second, change your focus. Think about your choices in a larger context—you may realize that your money will be better spent on something more rewarding in the future.

Irrationality Trigger #2: Anchoring

Often, you’ll find that your idea of a fair price for a product doesn’t match another person’s idea of a fair price. This is because of arbitrary coherence—your “right” price for an item is completely arbitrary, usually just the first price you saw that product listed for. Once you have a price in mind, it becomes a benchmark for all other prices for that product (coherence).

- For example, if you grew up in Hawaii, your idea of a fair price for a gallon of milk would be around $7—but for a Wisconsinite, a fair price would be around $2.95. The product is the same, but the idea of what’s a reasonable price depends on wherever you happened to grow up.

This process of establishing a product’s price as “normal” and making it the benchmark by which you judge all other prices for that product is called anchoring. You’re constantly influenced by prices—advertisements, the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP), a car salesman explaining a car’s value. A price “sticks” as an anchor as soon as you consider buying a product at that price. Though you may rationally be aware that prices must change depending on environment and circumstances, your anchors will irrationally inform your choices.

An anchor can easily develop into a long-term habit, through a process called self-herding—that is, if you have a positive first impression (your anchor, in a sense) of a decision you’ve made, such as trying a new product or restaurant, you’ll later make the same decision based on your memory of your first impression. Over time, you start to think that this behavior is a preference when it’s simply a habit built on that first impression.

These “preferences” often cost time and money—ask yourself what pleasure you’re getting from the habit.

- Is it worth the money you’re spending on it, or is it just a habitual decision?

- Would it be possible to cut back or spend your money elsewhere?

Irrationality Trigger #3: “Free”

“Free” is a powerful marketing tool because we’re inherently attracted to things that are free. Every transaction has an upside and a downside—you gain something, but you may have spent money on a dissatisfying purchase. “Free” eliminates the possibility of this downside, and does away with rational cost-benefit analysis.

- If you were offered a Belgian chocolate for 15 cents or a dollar-store chocolate for 1 cent, you’d likely do a quick cost-benefit analysis (as the standard economic model predicts) and choose the Belgian chocolate. It’s a very low price for a far superior product.

- If the price of each chocolate was lowered by 1 cent, there should be no difference to your choice because both prices are reduced by the same amount. But, instead of doing a cost-benefit analysis, you’ll choose the dollar-store chocolate, which is now free—pushing rational decision-making aside in favor of a transaction with no downside.

“Free” influences your choices even when it comes to products that must have a price (and therefore, a downside). By attaching “free” to a purchase, advertisers can trigger an irrational reaction that costs you more money. Online retailers practice this by offering free shipping on orders over a certain amount. This often costs you extra money in the end.

- For example, you’re shopping online and your total comes to $23.75. A notification pops up—you’re just $1.25 away from qualifying for FREE shipping. You add one more book to your order to snag the deal. That book cost you an extra $11, whereas paying for shipping would have cost just $4.

When you’re faced with something free, take a moment to question your decision-making. Ask yourself: If this wasn’t free, what choice would I make? Could I justify this purchase if the “free” part was eliminated?

Irrationality Trigger #4: Social and Market Norms

We all operate within two norms simultaneously. The first set of norms are social norms—requests are made and obliged because of the human need for connection and community. These social transactions have three key parts: they provide pleasure to both parties; there isn’t a need for immediate “compensation”; compensation isn’t monetary—it’s a reciprocal act of connection or community, such as inviting your neighbor for dinner to thank her for mowing your lawn.

The second set of norms are market norms—requests are made and obliged because they are expected and enforced. The key parts of market transactions are directly opposite those of social transactions: they’re not necessarily for pleasure; there’s a need for immediate compensation; compensation is monetary—non-monetary compensation is considered inappropriate.

Usually, you’ll keep these two worlds separate—you wouldn’t offer your friend payment for the dinner they cooked for you, or pay your employee with home-cooked meals instead of money. However, these two worlds occasionally mix—and the blurring of the two often creates irrational and unexpected outcomes. Sometimes, this will be to your advantage, but other times it can seriously damage pre-established relationships.

When you introduce market norms to social relationships, social norms disappear—often harming the social relationship permanently.

- For example, a daycare in Israel tried enforcing a late pick-up fee to encourage parents to be timely. Instead, the parents started showing up later—now that they were paying for the right to be late, they weren’t bound by the social expectations of being on time.

On the other hand, introducing social norms to market relationships usually has a positive outcome.

- For example, a group of lawyers refused when asked to significantly discount their fees when working with residents of a retirement home. However, when they were asked to volunteer their time and expertise to help the retirement home residents, they agreed. The social norms made them more interested in fulfilling social obligations than making money.

Furthermore, an experiment at MIT showed that people operating under unpaid social norms tend to work significantly harder than those operating under paid market norms. This suggests that the cultivation of social relationships is the best way to get people to do cheaper, more effective work for you.

- This idea extends to your workplace. While it feels more rational to have market relationships with employees, it’s more effective to create social relationships. Doing so taps into the sense of purpose, motivation, and loyalty that employees feel toward their work. You can accomplish this by fostering excitement about the work—for example, by reporting positive customer reviews or recognizing individual employees for excellent work.

Irrationality Trigger #5: Emotional Arousal

We think we know ourselves well enough to accurately predict decisions that we’ll make—but we don’t take into account that there are two selves driving our decisions.

- The first is who you are in a “cool state,” when you’re able to make decisions calmly and rationally.

- The second is who you are in an “aroused state.” In an emotionally aroused state—such as when you’re hungry, afraid, or sexually excited—you tend to make choices that are neither rational nor in your best interest.

Most people think that if they know their aroused self will act irrationally, they can train themselves to think clearly and rationally. However, experience with a particular aroused state doesn’t make you better at controlling how you act when you’re in that state again. The decisions you practice when you’re in a calm state won’t hold in your aroused state.

It might not be obvious, but procrastination stems from this discrepancy between cool state decisions and aroused state decisions. Procrastination is simply the abandonment of rational plans in order to indulge in whatever will appease your aroused-state emotions. You set your goals with the best intentions—while in your rational cool state. When your emotions are triggered, you naturally act in ways that aren’t aligned with what you want to do.

Because you can’t predict how you’ll act in an aroused state, you have to work against procrastination by creating natural guidelines toward rational decisions. There are three helpful anti-procrastination tools.

- Pre-commitments are promises or decisions your cool-state self makes that are aligned with the way you want to act. These commitments are made in such a way that when it comes time to act, you’re either held accountable to another person—such as a gym buddy—or the decision is made for you—as with an automatic savings plan.

- Breaking the cycle of random rewards is helpful if you spend too much time on things that should be put off until later, like checking your phone or email. These activities randomly deliver rewards such as a text from a friend, or an important email. When rewards aren’t predictable, they take on a surprising, addictive sheen; reducing the possibility of random rewards removes this temptation. Try putting your phone on Do Not Disturb while you work, or set your emails to chime only when an urgent email comes in.

- Creating positive associations can give you a type of “reward” for doing unpleasant tasks you usually put off, such as doing laundry or studying for exams. This helps fulfill your need for immediate gratification and prevents you from seeking it elsewhere. Try watching your favorite show every time you fold laundry to create an association between the two activities.

Irrationality Trigger #6: Ownership Bias

Ownership is an inherent part of our lives, but unfortunately, it drives us to make poor selling and buying decisions.

Irrational Selling Decisions

There are four particularities of human nature that drive poor selling decisions:

- You naturally start to love things as soon as you own them.

- You focus on potential losses more than potential gains.

- You assume that the buyer shares your view of the item.

- Your sense of ownership becomes stronger the more work you put into an item.

These particularities combine to create the endowment effect—that is, when you own something, you value it much more than other people do. This contributes to poor selling decisions in several ways.

- First, it’s harder to part with an object when you love it or are focused on its loss—driving you to price it exorbitantly, or not sell it at all.

- Second, when you price items you’ve put a lot of work into, you’re pricing based on your effort—not on the actual (lower) value of the item.

- Third, you’ll assume that your price is fair, because you know the item’s cost-worthy features. However, the buyer won’t see how the item is better than another, similar, lower-priced item.

It’s very difficult to think objectively about your possessions, but by recognizing how ownership colors your perspective, you can be more receptive to the advice of neutral parties—such as a friend or real estate agent. Their clearer ideas of the value of your possessions can help guide your decision-making.

Irrational Buying Decisions

Poor buying decisions stem from the fifth particularity of our nature—you can feel ownership of an object before you even own it. This is called virtual ownership, a powerful selling tool that usually comes in the form of advertisements and trial periods.

- Advertisements feed you a visual story where you can imagine yourself owning a product—which causes you to naturally fall in love with it.

- Trial periods, on the other hand, let you experience what it’s like to own a product. Because trials replicate the feeling of ownership, you’ll naturally start to feel that the product is yours and become averse to losing it.

In both cases, your lack of real-life ownership starts to feel like a loss—driving you to buy and therefore actually own, the product.

You can avoid the trap of virtual ownership in several ways. First, when you see an advertisement, think about how the product will really show up in your life. Second, avoid trial periods if you don’t need the product—once you “own” the product, it starts to feel like a need.

Irrationality Trigger #7: Options

It’s human nature to keep as many options open as possible. However, having too many options distracts you from your goals and causes you to miss out on disappearing opportunities. There are three ways to stop wasting time on insignificant options and commit to decisions:

1) Narrow your options. Recognize when options realistically have very little opportunity or potential and eliminate them from your thinking. Some of these options are insignificant and easy to dismiss—such as eliminating little-enjoyed activities from your children’s schedules. Other times, these options will be significant and difficult to choose between—such as choosing your major in college. In these cases, you’ll have to put a great deal of thought and commitment into deciding which option is the best choice for you.

2) Consider your losses. Even with only two options before you, you’ll spend time trying to decide which option is the “correct” choice. In these cases, focus on what you lose by not making a choice. For example, not committing to a major means you miss out on interesting electives, or staying in a fizzling relationship prevents you from creating happy memories with a new partner. While keeping many options open holds many opportunities, actually committing to one option is what grants you opportunity.

3) Recognize disappearing options. Examine options in the context of the long term—you’ll discover which options have a sense of urgency, because they won’t be available forever. These opportunities demand that you invest time and energy in them now. These options can be incredibly significant—such as choosing to spend more time with your children than on work—and other times, important in a small way—such as choosing to quit a club in order to spend more time enjoying your garden. This exercise eliminates options that don’t serve your best interests in the long term or can be revisited at a later time.

Irrationality Trigger #8: Expectations

Your perception of events is heavily colored by your expectations and knowledge going into an experience. This doesn’t just influence your belief of what happened—your expectations can physically modify your sensory perceptions.

- For example, in blind tests between Pepsi and Coke, most people prefer Pepsi. However, when people are told what brands they’re drinking, they overwhelmingly prefer Coke—their ideas of the brand physically modify the taste they experience.

Expectations—conscious and subconscious—exist in all facets of your life, and it’s important to try to keep them as unbiased as possible. While it’s difficult to “unlearn” the information that colors your experience of an event, you can find ways to make decisions and sort through problems as rationally as possible.

- You might present a neutral account of what happened to prevent people from arguing “their” side and highlight factual discrepancies. For example, instead of arguing, “You stole money from our savings for a ridiculous purchase, and you didn’t even ask me!” you could try, “Money was taken from our joint savings account for a large purchase that wasn’t agreed upon.”

- You could ask a neutral third party to help with arguments—such as a couples therapist.

The placebo effect is one well-known way that our expectations can drastically alter the outcome of an experience. The placebo effect is more nuanced than the simple belief that you are receiving effective medicine—experiments show that when medications and products come at a higher price, the placebo effect is stronger because we naturally associate quality and high prices. This means that companies and providers can not only influence how well we think products, procedures, or medications are working, but how well they actually do work—just by bumping up the price.

It’s a natural, unconscious reaction to think that low price is equivalent to low quality—putting in a moment of conscious thought goes a long way toward interrupting this irrational reaction. This moment of thought might look like reading the active ingredients in brand name and generic brand medications to objectively see that they’re the same medicine or reading user reviews when comparing two similar, but differently priced, products.

Irrationality Trigger #9: Trickle-Down Distrust

The rational way to consume resources is to commit to ensuring that resources aren’t exploited or depleted, so everyone can enjoy the benefits. However, there are often people and organizations that act in their short-term self-interest and destroy the resources for everyone in the long term. As a result, we naturally feel that we can’t trust organizations with public resources—they’ll exploit them, sooner or later. This general distrust of organizations has far-reaching implications.

First, we irrationally apply distrust to everyone instead of just the person or organization in question. For example, people are so used to seeing organizations use the word “free” as a sly marketing half-truth that they automatically think that any “free” offer must be a trick—so when a peer offers them something for free, they automatically distrust the intentions behind it.

Second, we’re more likely to engage in untrustworthy behaviors ourselves when we feel that others are not trustworthy. These dishonest behaviors may be beneficial in the short term, but they’re irrational because they only serve to continue the cycle of distrust. Those who do act with honesty are punished for doing so—men who don’t lie about their height are overlooked, or a candidate with an unembellished résumé doesn’t land an interview. In the future, they will also resort to untrustworthy behavior, because it’s the only way to be competitive.

If we worked toward building trust instead of spending energy on “winning” or avoiding being swindled, we’d be able to reap more rewards from our exchanges and transactions. The only way out of the ongoing cycle of distrust and untrustworthy behaviors is to become more trusting. There are two ways that you can accomplish this: consciously stop contributing to interpersonal distrust and engage with trustworthy organizations.

1) Consciously stop contributing to interpersonal distrust. Trust is an easily exploited resource—make sure that the way you communicate isn’t contradictory or doesn’t rely on confusing or hidden subtext. For example, make sure you always say what you mean. If you tell an employee that there’s “no rush” on a project, don’t become upset when they don’t start working on it right away.

2) Engage with trustworthy organizations. Working on interpersonal relationships helps establish small pockets of trust, but recall that most general distrust trickles down from distrust of organizations that exploit resources. To repair your general sense of distrust, engage with trustworthy companies that don’t demonstrate self-serving behaviors. Ask yourself: Does this company engage in initiatives that are in the interest of the common good, such as reducing carbon emissions? Is this company’s marketing misleading or dishonest?

Irrationality Trigger #10: Rationalized Dishonesty

We irrefutably think of ourselves as good and honest people, even though everyone is guilty of dishonest actions—like taking a roommate’s leftovers or swiping a few pens from work. Usually, your decisions about whether or not to act honestly depend on your conscience, which is essentially the internalization of social values. However, the influence of your conscience is only so strong—at times, the financial benefit of acting dishonestly can overpower your moral compass.

We put laws and oaths in place to prevent dishonesty, but the promise of financial benefit is strong. People easily find loopholes that allow dishonest dealings. For example, pharmaceutical companies can’t bribe doctors with money, but they can send them on nice vacations.

The key to being honest is recognizing the irrational mental gymnastics we go through in order to think of ourselves as honest while acting dishonestly. The type of dishonesty perpetrated by otherwise honest people is at least one degree separated from cash, because the absence of money makes it much easier for you to rationalize your actions. Rationalizations leave our consciences untriggered—we can believe that we’re honest people, despite the fact that we regularly engage in dishonest actions.

- For example, if you write off lunch with a friend as a business expense, you might think, “She works in a similar field so this was a valuable networking opportunity.”

The first step to becoming more honest is recognizing the ways you’ve rationalized dishonest behaviors. When you know your patterns of rationalization, it’s easier to spot them when they come up and consciously work against them. The second step is interrupting these thought processes by reframing your thinking—think about the cash value of your dishonesty. For example, if you’re about to write off that lunch as a business expense, ask yourself, “Would I take $100 directly from my company?”

Irrationality Trigger #11: Making Choices Aloud

When we make decisions aloud, we tend to be less satisfied with the outcome. This is because we tend to make very different choices in front of others than we would privately. And, when we make decisions aloud in a group, everyone in the group makes much more varied choices than if they were choosing privately. We do this because we have a need to project a certain “individual” image of ourselves to others. On the other hand, those who make decisions privately are more often satisfied with their choices—their decisions come from their preferences, not their need to prove something.

Be aware of this inherent need to make individual choices. While it may only result in a small unsatisfying decision—like ordering a drink you didn’t really want—it has the power to drive a large, life-altering decision—such as choosing a university you don’t love because a rival already chose your first pick.

It’s helpful to think ahead about your decisions, so you’re not tempted to change them in front of others.

- First, know what you want. If you wait to hear the decisions of others before making a choice, you’ll be easily influenced.

- Second, try to announce your decision first. Announcing your choice first puts a “claim” on the decision, and protects your individuality, even if someone else makes the same decision as you.

What Human Error Can Teach Us

Many of our practices are based largely on information about how people should act, but it’s clear that we should be more focused on learning how people do act. By doing so, we can find ways—irrational though they may be—to improve our communities and social relationships, make better choices for ourselves, and act with honesty.

(Shortform note: Read our summary of Thinking, Fast and Slow to learn more about how we make decisions, and why those decisions are often irrational)

Introduction to Behavioral Economics

The standard economic model that our world operates on is based on the idea that humans are rational creatures. This model assumes that when you’re presented with options or a decision to make, you’ll carefully weigh the benefits and drawbacks of each of your options, and choose the best possible outcome for yourself.

Furthermore, this model dictates that in the case you do act irrationally and make a poor decision, the flaw of your decision will be quickly revealed to you, you’ll realize your mistake, and you’ll avoid making the same mistake again in the future.

Behavioral economics, on the other hand, argues that humans are systematically irrational, often don’t recognize their mistakes, and don’t learn to make better decisions.

The emerging discipline of behavioral economics pushes against the standard economic model and seeks to understand why humans so frequently depart from perfect reasoning skills and how our everyday environments are used to influence and shape irrational behaviors and decisions.

Both experiments and real-life scenarios consistently reveal a significant quirk of human nature—we’re not only irrational but predictably so. Because we’re not conscious of when or why our decisions are irrational, we fail to correct our mistakes. Instead, we continue to repeat the same mistakes in such a predictable way that our irrational line of thinking can be used against us—by marketing agencies, employers, or even your real estate agent.

The good news is, it doesn’t need to be this way. In this book, Duke behavioral economist and best-selling author Dan Ariely untangles the common pitfalls of human logic and explores the forces that really drive your actions. Armed with this knowledge and awareness, you can consciously avoid the traps of irrationality and improve your decision-making skills to act in ways more beneficial to you.

Chapter 1: How Relativity Makes Decisions For You

It’s human nature to make constant comparisons in an effort to find guidance toward the “right” choice. This is why, as a general rule, people can’t pinpoint what they want until they see someone else with it. For example, if you were asked to shop for headphones, it’s likely you wouldn’t know exactly what to look for because you don’t know what makes for “good” headphones. However, if you spotted someone wearing a really sleek pair of headphones, you’d likely want to buy similar ones. Because someone else has those headphones, we assume that they’re a good choice.

Because of our need for guidance, relativity has a powerful influence on how we make decisions. Humans don’t have an inherent sense of the value of things or what the right decision is. Instead, we resort to surmising the value of an item by considering its relative advantage or disadvantage over another. However, these value-determining comparisons are often set up for us in a way that leads us to irrational choices.

An awareness of how we rely on relativity to make decisions is important because it influences all parts of your life—where and how you spend your money, how you choose who to date, and how satisfied you are with your life.

How Relativity Influences Your Purchases

Marketing agencies and salespeople understand that people naturally make comparisons, as a sort of decision weathervane. Subsequently, their advertisements and tactics are often framed to force you into making comparisons and drawing conclusions that are beneficial for them, not you.

The Decoy Effect

Many advertisers utilize the decoy effect. They present you with options, including a clearly unfavorable option—the “decoy”—to trigger a comparison that will guide you toward a specific choice.

Imagine that you see an advertisement for National Geographic subscription bundles. There are three options:

- Internet only: $59/year

- Print only: $125/year

- Internet and print: $125/year

The print-only option is the decoy—you’ll likely conclude that it’s a rip-off, because it makes no sense to pay $125 for just print when you could have the internet and print bundle for the same exact price. Furthermore, because the print-only price and the bundle price are the same, it seems that the bundle offers the internet subscription for free. Just as the advertisers planned, you’re thinking that the bundle is a very good deal.

It’s likely this is an irrational choice for you. Is it really necessary to have two media options? Perhaps you prefer to read print copies of magazines, or only intend to use the internet portion of your subscription. But, as it feels like the “right” choice compared to the other two, you’ll almost certainly choose the bundle.

Experiment: Magazine Subscriptions

For further proof of how drastically “decoys” can disrupt rational decision-making, consider the following experiment at MIT. In the first part of the experiment, the three subscription choices were presented to 100 students. As predicted, their choices were:

- 16 students: Internet only for $59

- 0 students: Print only for $125

- 84 students: print and internet for $125

In the second part of the experiment, the decoy was removed. Rationally, their choices should be exactly the same as in the first part, because the only option that was removed was the option that 0 students chose. Instead, the students responded as such:

- 68 students (up from 16): internet only for $59

- 32 students (down from 84): print and internet for $125.

The majority of students chose the internet-only option. This makes sense—the internet-only option is far cheaper, and university students are likely to only use the internet. This tells us that without the inclusion of an unfavorable decoy, we have a much greater capability to make rational decisions that suit our needs and preferences.

The Middle-Of-the-Road Decoy

At times, the decoy effect won’t be so obvious and there won’t be a clearly unfavorable option present. In these cases, you’ll look for information that can nudge you toward an option that feels safe or correct. Salespeople use this to their advantage, setting up options that act like gutter guards on the sides of a bowling alley, keeping you on a straight path toward the “middle” option they’ve already chosen for you.

This tactic can be hard to spot. Imagine that you’re shopping for a new television and you see three TVs set up together at the store:

- 36-inch Samsung for $500

- 48-inch LG for $825

- 60-inch Sharp for $1,560

As a customer, you’re unlikely to research how Samsung, LG, and Sharp measure up against one another and if the advertised prices are a decent deal or not. Instead, you’ll probably use the highest and lowest prices and biggest and smallest screens as comparative guidelines—and choose whatever’s in the middle. Your TV salesperson knows this, and prices his televisions and sets them up side by side to encourage this very thought process. In doing so, he guides you to the LG television (which likely turns him the largest profit).

This tactic could also look like a restaurant far overpricing something on the menu to maximize their profits. They do this because it’s been shown that restaurant-goers often won’t order the most expensive item on the menu, but they’ll very often order the second-most-expensive item on the menu. Therefore, when restaurants set their prices, they often list a dish that they’re not particularly interested in selling as their most expensive dish and will list a profit-turning dish they do want to sell a few dollars lower.

Beware of Easy Comparisons

One thing that compounds the trickiness of the decoy effect is the way we decide how much effort we’re willing to put into making comparisons. When making comparisons, we tend to focus on comparing things that are similar—therefore more easily comparable—and ignore things that are different and therefore less easily comparable.

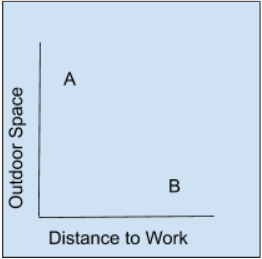

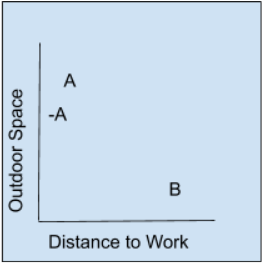

Many industries, such as real estate and travel agencies, play into this line of thinking. When you’re deciding between two options (A and B) and their accompanying attributes, you may be presented with a third option (-A), which is similar to—but worse than—one of the options. Because the two “A” options are more easily comparable than A and B, you’ll quickly reject the B option. Then, because the -A option is clearly worse than the A option, A will be your final decision.

Imagine that you’re looking to purchase an apartment. The two most important factors in your search are outdoor space and distance to work. You find two interesting apartments—a split home in the suburbs (A) and a brownstone in center city (B). The suburban option is superior in terms of outdoor space, but the brownstone is much closer to your work.

Your real estate agent then shows you a third apartment (-A): a suburban split home with a lot of outdoor space—but that outdoor space is directly next to busy train tracks.

With the introduction of apartment -A, your real estate agent has essentially made the decision for you. You’ll naturally reject apartment B, because it’s too different from the others, and therefore harder to compare. Then, you’ll choose option A as it’s clearly the better of the two suburban homes.

The Decoy Effect in Travel Agencies

The decoy effect is a common selling tactic in travel agencies. Imagine that you’re planning a trip to Europe, and your travel agent shows you two packages—one for Barcelona and one for Amsterdam. You’re having trouble deciding between the two because they cost the same, and both include flights, a hotel, and breakfast. Both are interesting destinations with much to see and do.

Then, your travel agent presents a third option: another Amsterdam package. It’s the same price as the others and includes flight and hotel, but it doesn’t include breakfast. Now your choice shifts—it’s not just Amsterdam and Barcelona now. It’s Amsterdam (A), Amsterdam without breakfast (-A), and Barcelona (B).

You’ll likely reject Barcelona right away, as it’s different from the others and not easily comparable. Then, because included breakfast is preferable to no breakfast, you’ll choose the Amsterdam (A) package—just as your travel agent planned.

Using Knowledge of the Decoy Effect to Make Better Purchases

The decoy effect is a powerful selling tool, but you can consciously work against it. When making purchases, think about why you’re making the comparisons that you’re making. Are you just looking for a middle-of-the-road price, instead of doing research? Were you presented with options designed to lead you toward a specific choice?

When you’re aware of how the decoy effect is being used to influence your purchases, you can make a rational decision by doing research or by committing to making smart comparisons, even if the two items before you are very different and will take a good deal of mental effort to compare.

The Decoy Effect and Dating

The decoy effect works the same way when you’re comparing people as it does when you’re comparing houses, televisions, or vacation packages. For this reason, it can actually have a heavy influence on who you find attractive or choose to date.

In an experiment at MIT, students were presented with three photographs. Two of the photographs were of person A and person B, both similar in looks and overall attractiveness. The third photograph was of person -A—that is, a slightly distorted image of person A. The students were asked to choose which of the three people they would prefer to date.

75% of the students chose person A. Following the decoy effect, they rejected person B because they were different and therefore not easily comparable, and then realized that person -A was clearly unfavorable compared to person A.

An interesting takeaway here is that you can use the decoy effect to your advantage when it comes to dating. Try going to the bar with a friend who has similar physical characteristics to you, but is slightly less attractive and see how it plays out in your favor.

- First, the people you’re chatting up will focus on you and your friend, as the crowd is full of dissimilar faces that are too difficult to compare.

- Second, when it’s down to you and your decoy friend (-you, in a sense), you’ll be the more attractive choice.

(Of course, don’t tell your friend what you’re up to unless you’re interested in destroying a friendship.)

How Relativity Makes You Miserable

A last important point to understand about relativity is how powerful it can be in making you miserable, even if what you have is objectively good. Your comparative nature reaches far beyond making purchases or choosing who to date—it can cause you to ceaselessly compare your life to the lives of others. Recall from the beginning of the chapter that people often don’t know exactly what they want, until they see someone else with it. This is why you were happy with your reliable Honda until you saw your neighbor’s new Tesla. Or, why your brother-in-law’s recent jet ski purchase made you suddenly want to get into boating.

Of course, this tendency toward comparison and subsequent envy comes with myriad problems. These problems can be smaller, such as the trap of comparative consumption you fall into when you need to have the same products as those around you. Other times, comparison and envy can translate into larger problems.

- For example, information about CEO salaries is often leaked as a way to create outrage toward the CEO and corporation in question and to push for fair wages for those at the bottom of the ladder. Instead, this often has the unintended effect of CEOs across the country realizing that their salaries could be even higher, and pushing for a salary equal to or better than the one leaked.

Finding Happiness Despite Your Comparative Nature

Relativity is all around you, and your perception is inherently colored by it. However, there are several ways you can control your comparison compulsion.

1) Diminish comparison opportunities. By controlling what products you see, you can exercise control over how tempted you are to make comparisons. For example, if you’re shopping for cars, be sure to only look at cars that are well within your means instead of casually browsing expensive, unwise choices. Looking at expensive cars will inevitably prompt you to compare them against your current car—which of course, makes the expensive car look like a good choice.

2) Change your focus. It’s helpful to think about your choices in a larger context—you may realize that you are making a decision that isn’t for the best, in the long term. Take the example of shopping for cars. In a moment of narrow focus, giving up your reliable Honda for a new Tesla might seem like a good choice. The Tesla has more features, self-parks, and doesn’t require gas, and your Honda is a little on the older side anyway. However, reconsider this choice within a larger context. If you don’t buy the Tesla, you’ll save yourself a great deal of money, which could probably be better spent. You could eventually buy a new reliable Honda and have money left over to take your family on a vacation.

In the end, it’s important to understand how strong the influence of relativity can be on your decisions and your desires. With the awareness that your choices might not be sound, you can consciously work against your natural tendency to make comparisons. Instead, focus on doing thorough research before making purchases, putting extra mental effort into making comparisons between dissimilar items, and focusing on what you do have instead of what you could have.

Exercise: Think About How the Decoy Effect Has Influenced You

Stopping the decoy effect from influencing your decisions depends on being aware of what faulty or forced comparisons look like in your life.

Think of the last purchase you made where you had to choose from a set of options (for example, purchasing a new refrigerator or selecting from a menu at a restaurant). What decision did you make?

What factors led you to the option you ultimately decided on? (For example, the fridge model seemed to be the best value, or the lobster was a good price.)

Looking back, how do you think the decoy effect may have influenced your purchase? (For example, the fridge you chose was the mid-price model in the shop, or the lobster was the second most expensive item on the menu.)

How would you have made the decision differently, if you were conscious of how relativity was a factor?

Exercise: Break the Cycle of Comparative Consumption

Practice diminishing your comparison opportunities and broadening your perspective to avoid the irrational purchases that relativity can encourage.

Think of a large purchase you’re considering. What is the purchase, and what prompted you to first consider making it?

How do you think comparison may be influencing your decision to make a purchase? (For example, your friend got a jet ski and now you want one, or you recently saw an SUV that’s nicer than your current car.)

How can you diminish your comparison opportunities? (For example, not researching jet skis, or committing to not going to the car dealership.)

Change your focus—what could that money be better spent on? (For example, you can go on vacation and rent a jet ski, or you can put the SUV money toward a house.)

Chapter 2: How We Unreasonably Determine Reasonable Prices

Often, you’ll find that your idea of a fair price for a product doesn’t match another person’s idea of a fair price. This disparity can be explained by the concept of arbitrary coherence—the “right” price you assign to an item is completely arbitrary. Usually, it’s simply the first price you saw that product listed for. But, once you have that price in mind, it influences how you think of the present and future prices for that product (coherence).

- For example, if you happened to grow up in Hawaii, your idea of a fair price for a gallon of milk would be around $7. However, imagine if you lived in Wisconsin—where milk runs about $2.95 a gallon—before moving to Hawaii. You’d find Hawaii milk prices ludicrous. The product is the same, but your idea of what it should reasonably cost is based on the milk prices wherever you happened to grow up.

This process of establishing a product’s price as “normal” and making it the benchmark by which you judge all other prices for that product is called anchoring. In this chapter, we’ll discuss just how irrational these anchor prices can be, and then examine how anchors can compound into long-term irrational decisions.

How You Set Anchors

The figure you establish as “normal” is completely arbitrary—so it makes sense that anchoring can be triggered by any figure. One experiment at MIT set out to explore this idea, using the digits of students’ social security numbers.

Experiment: Anchoring With Social Security Numbers

The participants were shown several objects up for silent auction—including several well-aged bottles of wine, Belgian chocolates, a book, a wireless mouse, and a keyboard and mouse package. Each participant received a list of the items and was asked to write the last two digits of her social security number at the top of the page. Then, they wrote those two digits next to each item in the form of a price (25 → $25, for example). Lastly, the participants indicated a) whether they would pay their listed price for each item, and b) what bid they’d prefer to place on each item.

The results revealed that those with social security numbers ending in higher digits (80 to 99) were more likely to bid higher on each item, and those with lower social security numbers ending in digits (01 to 20) were likely to bid the lowest.

What Might Anchoring Look Like for You?

While this experiment demonstrates that social security numbers can be effective anchors, it’s important to understand that any number can have the same effect—the first two digits of the students’ phone numbers, for example. Of course, you don’t create anchors in your everyday life by thinking about your telephone number or social security number.

Rather, you are constantly influenced by prices—advertisements, the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP), a car salesman explaining a car’s value. As soon as you consider buying a product at a particular price that’s been put before you, that price “sticks” as an anchor. You may rationally be aware that product prices must change depending on environment and circumstances, but irrationally, these anchors will continue to inform your choices.

These choices may be small, such as determining that milk in Hawaii is too expensive based on your experience with milk prices in Wisconsin. Other times, anchoring might drastically affect how you make large decisions, such as looking for housing.

- For example, when moving from Lancaster, Pennsylvania to Boston, you may rationally expect housing prices in Boston to be much higher. Nevertheless, you will irrationally—yet automatically—reference your anchor prices from Lancaster when looking for an apartment. This will drive you to downsize rather than spend more on housing than you’re used to.

Experiment: Do Anchors Influence Future Decisions?

An experiment at MIT set out to determine if your anchors affect future purchases as well as those you make right after encountering an anchor.

In the first part of the experiment, two groups of participants had to listen to three 30-second clips of annoying sounds. After listening to the sounds, Group A was asked if they’d be willing to listen to the sound again for 10 cents, and to name the lowest payment they’d accept for listening to the sound again. Group B was asked the same questions, but their anchoring rate was 90 cents.

The results showed that participants in Group A asked for much less money to listen to the sound again (an average of 33 cents) than participants in Group B (who asked for an average of 73 cents).

In the second part of the experiment, participants from both groups listened to 30 seconds of a new annoying sound and were asked if they would listen to the sound again for 50 cents. Then, they had to indicate how much they’d ask to be paid to listen to it again. The results showed that Group A asked for a much lower payment than Group B—even though they’d both been presented with the new anchor of 50 cents.

These results suggest that our anchors, once established, influence our present decisions as well as our future decisions. In short, we tend to stick with our first impressions, even when they may not be rational—and knowing this is key to spotting your vulnerability to making irrational decisions based on impressions.

Making Decisions Based on Herding

To understand how an anchor can translate into long-term habits, it’s important to first understand the concept of herding. Herding is when you observe the behaviors of other people to decide if something is good or bad and copy the crowd’s behavior. For example, if you see a line of people waiting to get into a restaurant, you’ll determine that it’s a good restaurant and might also hop in line.

What’s interesting is that you can also perform self-herding—you decide if something is good or bad depending on your own past behavior, and you continue copying that behavior. In this way, a positive first impression (anchor) about a decision you’ve made can result in a long pattern of copying your own behavior. Eventually, you believe this behavior is your preference and not just an echo of that first decision.

Example: The Sandwich Shop

On a whim, you decide to get a sandwich at the artisanal deli down the block from work, instead of going to Subway as usual. The sandwiches, while they’re much more expensive, aren’t much different. However, the deli has a nice perk—comfortable couches and a fireplace to enjoy while you eat. Overall, you form a positive first impression about the deli—which becomes the anchor underpinning your future lunchtime decisions.

The next week, you’re thinking about where to go for lunch. Rationally, you should think through your options while considering the cost of the food, the distance from work, and so on. Instead, you simply recall that you tried the deli and that you enjoyed the experience. Based on this positive first impression, you determine that the deli is a good choice and go again. So begins the process of self-herding.

The third week, you recall your two previous decisions to go to the deli and go again—a bit like getting in line behind the people queuing outside a restaurant. Based on the fact that you keep going to the deli, you may believe that it’s your preference. In fact, it’s just your primary decision compounded into a habit. Habits built from self-herding often aren’t the most rational choice. You know, rationally, that Subway is closer to your office and offers a similar product for a lower cost. But, because you continue going to the deli, you irrationally believe that you’re making a conscious decision about how you want to spend your money.

The Circumstances That Can Set New Anchors

Since the products are similar, shouldn’t you be anchored to Subway’s prices, and realize that the cost of the artisanal sandwiches is too high? Rationally, yes. However, because the artisanal place feels so different, it becomes a first impression, instead of being comparable to the Subway. If the deli had a very similar aesthetic to Subway, you’d likely realize that the high prices weren’t the best use of your money. But the fact of the matter is, the food looks nice and there are nice window seats—in your mind, it’s a completely different type of place and the higher prices are justified.

(Shortform note: For more examples of anchoring and how it works, read our summary of Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.)

Making Better Decisions

Thinking rationally about your behaviors can help you untangle habits from your true preferences—allowing you to spend your money in more fulfilling ways. In examining your “preferences,” ask yourself several questions:

- How did this preference start?

- What pleasure am I getting from this preference? Is it worth the money and time I spend on it?

- Is it possible for me to cut back? Is there a wiser way I could be spending this money?

You can also prevent yourself from forming future habits by giving extra thought to your first decisions to do something. Would you want it to become a long-term habit?

Why the Supply & Demand Model Doesn’t Make Sense

The implications of price anchoring and our tendency to make irrational decisions based on our own past behaviors and impressions are much further-reaching than choosing a favorite sandwich shop. In fact, we should be rethinking the standard supply and demand model. Standard economics would tell us that prices are determined by demand—the higher the demand, the more people are willing to pay for a product.

However, we know this model doesn’t make sense, because our anchors are so arbitrary.

- First, people often aren’t aware of their anchors, so it’s hard to accurately predict how much they’d be willing to pay for a product.

- Second, anchors can be manipulated very easily—simply thinking about several random digits can create an anchor.

These findings of behavioral economics suggest that it’s actually the prices themselves, or the anchoring that happens on the supply end of the system, that influence how much people will pay.

Furthermore, the discussion of self-herding tells us that looking at peoples' preferences won’t give you accurate information about their willingness to pay for products—their demand is based on their memories. The aversion we feel to paying a higher price for a product is because we remember how much we paid for it in the past (or the anchor we established when we considered buying it), and we want our present decisions to be coherent with our past decisions. Of course, this means that over time, your anchors can naturally change.

- For example, if the price of milk in Wisconsin jumped from $2.95 to $5 overnight, there would be a steep drop in demand because the memory of $2.95 gallons would be fresh in everyone’s minds. However, as they continue needing to buy $5 milk over time, the decision to do so becomes a habit—decisions coherent with previous decisions. Over the long term, their memories of the $2.95 gallon would fade and demand for milk would steadily increase back to where it was before.

Exercise: Question Your “Preferences”

One way to help ensure that you’re making rational choices is to reflect on the reasons you’re making those choices.

Think of one of your purchasing habits (for example, a latté every morning, or a new iPhone every time a new model comes out). Describe the habit.

How did this habit start? Try to think back to your first decision to purchase this product.

Think about if this habit is really a preference—how much pleasure or satisfaction do you get when you indulge in it?

How could you cut back on this habit, or alter it so that it costs you less money?

Chapter 3: The Power of “Free”

In this chapter, we’ll discuss the concept of “free,” how it’s used to trigger irrational choices, and its potential for driving positive social change.

“Free” is a powerful marketing tool because we are inherently attracted to things that are free. This is because almost every transaction has an upside and a downside. The upside is that you gain something from the transaction. The downside is that you’ve spent money and it’s possible you won’t be satisfied with your purchase.

“Free” eliminates the possibility of a downside in a transaction. There’s no risk that your money will be spent on a dissatisfying purchase. Furthermore, because the free item is upside-only, you perceive it as much more valuable than it really is. For these reasons, you’ll naturally choose a free item above all else, even when it’s not the most rational choice. The following experiment illustrates how the possibility of getting something for free can interrupt rational thought processes.

Experiment: The Chocolate Sale

In this experiment, a chocolate-selling stand was set up in one of MIT’s student centers.

- In the first part, customers had the choice between a Lindt truffle for 15 cents, or a Hershey Kiss for one cent. In this scenario, 73% of the customers chose the Lindt truffle. This was a rational choice—not only was the Lindt truffle an objectively superior product, but it was being offered at a very attractive price.

- In the second part, each chocolate’s price was lowered by one cent. Now, the Lindt truffle was 14 cents, and the Hershey Kiss was free. Even though the Lindt truffle was still a superior product at a great price, the label of “free” on the Kisses had more power—this time, 69% of the customers chose the Hershey Kiss.

This behavior is especially interesting because it contradicts the standard economic model, which would predict that, because both chocolates were reduced in price by the same amount, there should be no difference in purchase rates. Customers would do the same simple cost-benefit analysis as when both chocolates came with a cost, and conclude that the Lindt truffle would be a far more pleasurable experience for a very small cost. However, the standard economic model doesn’t take into account the power of “free.” Instead of thinking through a cost-benefit analysis, humans quickly push rational decision-making aside in favor of a transaction with no downside.

Even Attached to a Price, “Free” Works

It’s fairly common sense that when you’re presented with two products—one free and one at a price, no matter how small—that you’ll choose the free item. However, what’s less common sense is that “free” has the power to influence your choices even when you’re choosing between two products that must have a price. Just by attaching the concept of “free” to a purchase, advertisers can trigger an irrational reaction in you that benefits them, and costs you more money.

You’ll commonly see online retailers putting this in practice by offering free shipping for orders that exceed a certain amount. While free shipping may feel like a good deal, it often costs you extra money in the end. Imagine that you’re shopping on Amazon, and your total comes to $23.75. You receive a notification that you’re just $1.25 away from qualifying for FREE shipping. You add one more book to your order and successfully snag the free shipping deal. The problem? The book you added cost you an extra $11, whereas paying for shipping would have only cost you $4.

If you’re skeptical that it’s truly the idea of “free” that triggers this reaction and not just low-cost shipping, consider what happened in France when Amazon rolled out their free shipping concept. Instead of free shipping, Amazon.fr chose to offer shipping at the very, very low cost of one franc (20 cents). When the shipping was a low cost—even a negligible amount like one franc—customers acted much more rationally and made fewer impulse purchases to push their order amount to the threshold for the shipping discount.

While falling victim to the trap that “free” presents might not be a big deal on smaller purchases like books, be careful not to let it influence the way you make larger decisions, like buying a new car. Imagine you’re looking for a new car for your family—you have the choice between a sports car and a sturdy SUV. The SUV costs a bit less and rationally, is a better match for your needs. However, your salesperson mentions that the sports car comes with free oil change for four years. Triggered by the idea of getting something for free—and irrationally, thinking that these oil changes will make up the difference in cost between the two cars—you spring for the sports car.

Diminishing the Power of Free

The first part of diminishing the power that “free” can have is recognizing the ways it might be showing up in different aspects of your life. Keep in mind that it’s not only used to trigger irrational purchases. It can also be used to manipulate how you spend your time—you wouldn’t spend 45 minutes standing in line for ice cream unless it was Free Cone Day at Ben & Jerry’s or unless each ice cream came with a free t-shirt.

The second part is questioning how the presence of “free” might be affecting your decision. Take a step back and think:

- If this wasn’t free, what choice would I make?

- Would I be able to justify this purchase or time spent if the “free” part were eliminated?

Taking a moment to think consciously about why you might be making certain choices is a helpful step in interrupting the natural, yet irrational, reaction we have to free items—thus clearing the way for a more careful and rational analysis of what the best choice is.

The Positive Power of Free

It’s important to keep in mind that the power of “free” can be used toward positive outcomes if harnessed correctly. First, we’ll look at an example of how you can use it on a small scale in friendships, and then we’ll discuss how the power of free can drive social changes.

Dinner With Friends

Knowledge of humans’ natural positive reaction to “free” can help you strengthen the bonds of your friendship group—all you need to do is pick up the tab at your next outing.

Recall that nearly every transaction has the downside of having to spend money. If all of your friends need to chip in a bit for their portion of dinner, everyone at the table experiences this downside. However, the negative feelings associated with spending money only worsen to a certain point, and then plateau.

Imagine that every $20 spent is one unit of discomfort, and this discomfort plateaus around $60. If you and five friends went for dinner and each owed $20 at the end of the night, your group would experience a total of 6 units of discomfort. However, if you were to pay the entire bill yourself, you would only experience 3 units of discomfort and would spare the rest of your group any discomfort at all.

Ideally, another friend would have the responsibility of picking up the check at the next outing, and another at the outing after that. This continues the cycle of diminishing the downside of the transaction and thereby increasing the perceived value of the get-together, and it triggers the positive emotions that come with getting something for free.

Social Change, for Free

Another positive aspect of “free” is its potential for getting people to participate in programs that benefit their communities, their health, or the environment. For example, to encourage more people to drive electric cars, you could add the influence of “free” to the purchase—such as in an offer for free emissions testing or free weekend parking in your city. Or, to encourage more people to get preventative medical exams, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, make these exams free. Reduced copays don’t spark the same amount of interest or motivation as zero-cost copays.

Exercise: Think About How “Free” Triggers You

Knowing how you tend to behave when “free” is in the equation can give you valuable insight into your vulnerabilities, helping you stop its influence.

When was the last time you got an item—or a feature of an item—for free? Describe the transaction.

Was this item or feature truly free, or did you have to pay for it in time or money? (For example, you bought an overpriced printer because it came with 2 free ink cartridges, or you spent several hours in line waiting to get into a museum for free.)

If this item or feature hadn’t been free, would you have been able to justify this choice, or would you have made a different choice?

How can you commit to looking out for the influence of “free” in the future? (For example, looking on Groupon for discounted museum tickets, or crunching the numbers to figure out how much those two ink cartridges really saved you.)

Chapters 4-5: Navigating Social Norms and Market Norms

In this chapter, we’ll discuss the concepts of “social norms” and “market norms” and the unexpected choices we make when these two worlds collide.

We all operate within two norms simultaneously. The first set of norms are social norms—requests are made and obliged because of the human need for connection and community. These requests look like asking a friend to help you move, or cooking a big meal for your family. These social transactions have three key parts:

- They provide pleasure for both parties.

- There isn’t a need for immediate “compensation.”

- Compensation isn’t monetary—it’s a reciprocal act of connection or community, such as inviting your neighbor for dinner to thank her for mowing your lawn.

The second set of norms are market norms—requests are made and obliged because they are expected and enforced. These transactions look like a tenant paying their landlord rent, or an employer paying their employee’s wages. The key parts of market transactions are directly opposite those of social transactions:

- They’re not necessarily for pleasure.

- There’s a need for immediate compensation.

- Compensation is monetary—non-monetary compensation is considered inappropriate.

Usually, you’ll keep these two worlds separate—you wouldn’t offer your friend payment for the dinner they cooked for you, or pay your employee with home-cooked meals instead of money. However, these two worlds occasionally mix—and the blurring of the two often creates irrational and unexpected outcomes. Sometimes, this will be to your advantage, but other times it can seriously damage pre-established relationships.

First, we’ll discuss an experiment that explains how our mindsets change when shifting between social and market norms. Then, we’ll explore the various ways that the blurring of these norms can affect your relationships in unexpected ways.

Experiment: How Norms Drive Work Ethic

Part 1: Monetary Compensation

Three groups of participants were tasked with dragging an image of a circle into the image of a square on a computer. They were instructed to drag the circle into the square as many times as they wanted in the experiment’s 5-minute span. Each group received a different payment:

- Group A received $5 for their participation.

- Group B received between 10 and 50 cents for their participation.

- Group C was not paid—instead, they were asked to participate as a favor.

The results showed that on average, Group A performed significantly more circle drags than Group B—this tells us that under market norms, people will work harder when their payment is higher, as we might expect. However, the results also showed that the unpaid Group C dragged more circles than both paid groups. This reveals that people operating under social norms will generally work harder than those operating under market norms.

Part 2: Non-Monetary Compensation

The participants were asked to perform the same task but would receive small gifts instead of monetary compensation.

- Group A received a box of chocolates worth $5.

- Group B received a candy bar worth 50 cents.

- Group C was asked to participate as an unpaid favor.

Under these new conditions, the results showed that all three groups put an equal amount of effort into the task, matching the effort of Group C from the experiment’s first part. These results suggest that gifts as compensation stay within the social norms that drive a higher work ethic.

Part 3: Non-Monetary Compensation Attached to Monetary Ideas

The participants were given the same task and again offered small gifts as compensation. This time, the experimenters told participants how much their gift was worth—Group A was told that they’d receive a 5 dollar box of chocolates, and Group B was told that they’d receive a 50-cent candy bar.

The results showed that those who received the more valuable box of chocolate worked significantly harder than those who received the chocolate bar—in other words, they acted the same way as participants who were compensated with money. These results suggest that the mere mention of monetary value is enough to push us out of social norms into the world of market norms.

Imposing Market Norms on Social Relationships

You should be careful when introducing market norms to social relationships because doing so causes social norms to disappear—often harming the social relationship, sometimes permanently.

A great example of this is a daycare that was having problems with parents regularly arriving late to pick up their children. They rationally—but mistakenly—assumed that this problem would be solved if they charged a small fee for late pick-up.

Under the previous social norms, the parents were motivated to get to the daycare on time in order to avoid the embarrassment of inconveniencing their children’s caretakers. However, once the daycare introduced a monetary fee, replacing the established social norm with a market norm, the number of late pick-ups increased significantly. The parents now felt that they were paying for the right to pick up their child late and were no longer motivated by the social obligation to be on time.

Realizing their mistake, the daycare removed the fine—but the damage was already done. The social norm no longer existed, and the high number of late pick-ups continued.

Why Corporations Should Avoid Social Norms

Another area where you’ll commonly see problems with the mixture of market and social norms is in businesses that market themselves as a “friend” of their clients. These businesses work hard to create a relationship that appears to operate on social norms. While this might have the short-term benefit of capturing the client’s trust, it’s a mistake. Because corporations and their policies inherently operate under market norms, they’ll frequently need to impose those market norms on the social relationships they’re constructing, violating the relationships irreparably.

For example, a car insurance company that’s branded itself as your “partner” may need to deny your claim and put you out thousands of dollars. By doing so, they’ve violated a serious social boundary—instead of sticking to the non-monetary, favor-based relationship in line with their image, they’ve imposed a financial transaction on your relationship. This permanently damages their relationship with you, who will never again think of them as a “partner” who has your best interests in mind. Their reputation as a trustworthy company is further tarnished when you tell people about your poor experience.

Imposing Social Norms on Market Relationships

While imposing market norms on social relationships usually has a damaging outcome, imposing social norms on market relationships usually has a positive outcome. Money is the most expensive, but least effective, way to get people to do what you want. Instead, you should focus on cultivating social relationships and establishing social norms—as the circle-dragging experiments revealed, social norms lead to more effective work, for a much cheaper price.

This idea is applicable on a small scale—you know it makes sense to ask a friend to help you move as a favor, instead of paying up for professional movers. Your friend will likely work as hard as—or harder than—the movers, and you’ll save a good deal of money. The idea is also applicable on a larger scale—as an employer, you can create a more effective workplace by imposing social norms on the way you compensate your employees.

Navigating Social Norms With Employees

While it may feel more rational to focus on market norms in relationships with your employees, it’s more effective to create a sense of social norms. Creating social norms within your workplace taps into the sense of purpose, motivation, and loyalty that employees feel toward their work. They’re willing to work harder when they feel a sense of security in their job and can trust that their employer will help them in hard moments. You can establish social norms and this sense that you are a partner to your employees in several ways.

One way is to make sure your employees have robust medical benefits, but this can become expensive, and at times blurs market and social norms dangerously. For example, if your medical plan requires high deductibles or the amount of money you’re putting into medical benefits appears on your employees’ payslips, the benefits no longer feel like a favor or perk.

Another way to cultivate social norms is to offer your employees gifts instead of money—these can be small and personal, like a subscription box of their favorite teas, or much larger, like a week-long trip in a sunny location. However, while gifts will keep you safely in the realm of social norms, the costs will eventually start adding up in a big way.

(Shortform note: Read our summary of The Power of Moments to learn how small, personal gifts can boost employee satisfaction and motivation.)

The best—and cheapest—way to cultivate social norms in your workplace is to foster excitement and purpose for the work. When people feel that carrying out their purpose is a type of compensation in itself, they’re more willing to overlook a low monetary salary. This can work very well for startup companies—often, they aren’t able to pay their employees a high salary from the beginning. Instead, they should focus on creating excitement around the idea of building a product together. This can look like regularly reporting positive customer reviews of the product, or putting time aside every week to acknowledge the above-and-beyond work of excelling employees.

If you’re interested in cultivating social norms with your employees, it’s crucial that you commit yourself to the work and maintain social norms at all costs. Otherwise, if you decide to violate social norms in favor of market norms, you’ll inevitably and permanently damage your social relationships with your employees. Once your employees feel that they don’t have a social relationship with you—and thus aren’t bound by the ideas of loyalty and commitment—they will look toward market norms to make the most beneficial decisions for themselves. This may lead to losing a good employee or being forced to give an employee a steep raise in order to keep them on your team.

Revisiting the Power of Free: Why It Makes Us Less Selfish

Thus far, we’ve discussed how market norms and social norms work when you’re offering compensation to others for their services. In this section, we’ll examine how market norms and social norms may affect the way people act when compensation is demanded of them.

First, we’ll discuss the standard economic laws of demand, and how these laws are bent when products are free. These laws state that when the price of a product is lowered, the demand for the product will increase, for two reasons:

- More people are in the market because they can now afford the product.

- When the price is lower, each person is likely to buy more units of the product.

Based on the standard economic model, you’d rationally assume that if you offered a product for free, the demand would increase substantially. Everyone would be able to “afford” the product, and each person would want more than one unit of it. But, as the following experiment reveals, standard economics doesn’t take into account how “free” changes these laws.

Experiment: Free Candy

A candy stand was set up in an MIT student center. In the first round of the experiment, the candies were sold at the low price of 2 cents apiece. In the second round of the experiment, the candies were free.

- While only 58 students purchased the low-cost candy, 207 students took the free candy—rationally, the lower price meant that more people were in the market for the product, supporting the first law of demand.

- On the other hand, the second law of demand didn’t hold up. When the candies came at a cost, most students purchased a handful—and it was expected that rationally, they’d take even more when the candies didn’t cost anything. However, when the candies were offered for free, the students only took one or two candies each, leaving plenty for other students to enjoy.

These results suggest that when we’re operating under market norms, we adopt a more selfish mindset. However, when things are free, we operate under less selfish social norms and act in ways that benefit everyone.

Sticking to Social Norms Can Create Better Societies

The knowledge that people become more altruistic outside of monetary transactions can have interesting implications for our communities—as long as we focus on maximizing the social exchanges in our lives and are careful to prevent them from slipping into market norms. For example, while hiring a public safety officer might feel like the rational choice for a safe neighborhood, it would likely be more effective to put a Neighborhood Watch program in place for your community. Bound by the obligations of community, your neighbors would be more proactive in helping in one another and looking out for one another.

Furthermore, policymakers should be attuned to the ways that market norms and social norms affect selfishness. Many policies and practices aren’t effective because they’re based on market norms—pushing corporations and individuals to act selfishly, perhaps creating even bigger problems. A good example of this is the Cap and Trade program meant to reduce carbon emissions by fining corporations who exceed their set emissions limit. Rationally, the threat of being forced to pay a huge fine would cause corporations to adopt more ecological practices. However, the Cap and Trade program imposes a market norm on a social responsibility by putting a price on pollution. Large, well-funded corporations can easily justify the small price of paying for excessive carbon emissions because they can expand and outsource, thereby maximizing their profits.

A better way to handle this would be to remove the monetary exchange and push social norms, perhaps by requiring corporations to send their pollution information to their shareholders or post their pollutant information on their packaging.