1-Page Summary

The way the business world operates, according to software developer and management expert Jeff Sutherland, is fundamentally flawed. In Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time, he explains the Scrum framework, which he positions as a better time-management system than the traditional top-down approach. By using the carefully structured yet open-ended Scrum framework, a company, or any project team, can become much more efficient and productive.

Jeff Sutherland is a software developer who co-created Scrum alongside fellow software developer Ken Schwaber. A former fighter pilot and Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Medical School, Sutherland has since helped dozens of businesses implement Scrum into their development process.

What Is Scrum?

Scrum is a framework made to help people and organizations efficiently solve complex problems with creative solutions. Scrum is designed to be simple, and it’s based on a simple idea: When working on a project, check in regularly to make sure you’re heading in the right direction, and remove anything that might be slowing you down. The pillars of Scrum are incremental progress and adaptability rather than following a carefully prescribed plan. Applying the Scrum framework will help companies produce more value in less time by eliminating waste and maximizing time.

How the Scrum Framework Remains Adaptable

The Scrum framework emphasizes adaptability, and as such, the Scrum framework itself is constantly evolving along with the rapidly changing worlds of business and technology. Sutherland, along with Scrum co-creator Ken Schwaber, regularly updates the Scrum Guide, which they first wrote in 2010. Sutherland and Schwaber last updated the Scrum Guide in November 2020, and they reiterate the idea that the Scrum framework’s simplicity allows it to be adapted and used across multiple fields and domains.

Furthermore, this simplicity and adaptability allow for flexibility within the framework. For example, software company LinearB offers a free software tool that helps you further increase productivity, shorten development time, and increase employee fulfillment, building on the basic Scrum framework and adjusting it to suit their specific needs.

Scrum Versus a Traditional Management System

Within the Scrum framework, Sutherland advises that your team constantly inspect its methods and processes so that you can adapt to problems or changes in real time. This contrasts with a traditional project management style where you'd wait to finish a pre-planned stage and then review your results—by which time it's often too late to fix issues.

(Shortform note: In general, it's good practice to assess your work as you're working on it. Waiting to review something until after it's complete can waste a lot of time and energy. This can be used in your daily life as well. Instead of waiting until the end of the month or end of the quarter to review your own performance, why not do it every day? One expert recommends you write down your daily routine and go over it to determine how to better spend your time.)

Basic Scrum Framework

The basic techniques of the Scrum method that Sutherland outlines start with building an effective team. The next step is assessing and prioritizing the needed tasks, and then finally, approaching those tasks through Sprints—short, focused bursts of work.

Build and Maintain an Effective Team

In modern businesses, Sutherland insists, too much emphasis is put on individual achievements, rather than the team’s accomplishments. But he argues that the team, not individuals, is creating a product, so it’s important to focus on collective performance. This holistic approach to management, emphasizing teamwork, is a pillar of the Scrum framework.

Sutherland proposes three roles within a Scrum team:

- Product Manager

- Scrum Coach

- Developers

Product Manager

The Product Manager creates the overall vision for the product and makes sure the product is both viable and valuable. The Product Manager’s responsibilities include determining the goal of the project and what it should look like when it's finished and creating the task list of everything that needs to be done to complete the project.

(Shortform note: In Inspired, Marty Cagan agrees with Sutherland’s basic framework of having a product manager direct the vision of the project and oversee its task list. Cagan emphasizes that the person in this role be clearly a project manager rather than a product manager—in other words, this person oversees the work and the process, not the technical details of the product itself. Although Sutherland uses the word “product” in his title for this role, he sees the role in the same way Cagan does.)

Scrum Coach

While the Product Manager is responsible for making the product valuable, the Scrum Coach is responsible for making sure the team is working as efficiently as possible. She coaches the team in the ways of Scrum and keeps the team working within the Scrum framework. The Scrum Coach does this by encouraging the team to self-organize and share knowledge and removing impediments to the team’s progress. She doesn’t assign specific tasks but instead ensures that communication is open and the team is making consistent progress.

(Shortform note: The 4 Disciplines of Execution discusses the way organizational coaches can help implement a company’s vision. An internal coach benefits an organization by providing the team with the information or support they need and training new employees or leaders in the ways of the organization.)

Developers

The Developers are responsible for completing the items from the task list. They’re the ones building the product with guidance from the Product Manager and Scrum Coach. The Developers decide how to complete the tasks within each Sprint and are responsible for executing them.

Although the Scrum Coach makes sure everyone is working within the Scrum framework, the Developers must still hold each other accountable. Because the Scrum framework gives the Developers the freedom to work as they see fit, it's their responsibility to create consistent value within each Sprint.

(Shortform note: In Inspired, Cagan calls the team members with this role engineers. He notes that because the engineers will understand the product in more detail than the project manager will, they’ll be able to come up with creative, realistic solutions to problems. This aligns with Sutherland’s ideas for this role, in which the developers figure out how to approach the specific tasks while the Product Manager focuses on the big picture.)

Assess and Prioritize Tasks

When starting a project, Sutherland says the first step is to develop the overall vision you have for your company: what problems you’re going to solve, what you’re going to make, how you’re going to make it.

To do this, he advises that you create a task list, or what he calls a “backlog,” of all the things that need to be done to make your vision a reality. The task list should include every possible task that might be needed for the end product.

Then, with the task list complete, go through the entire list and rank each item by importance. Ask which tasks will have the biggest impact and create the most value for the customer, as well as which will be the most profitable and which will be the easiest to complete.

Once you have a clear picture of which tasks will bring the most value in the least amount of time, he advises that you simply begin working on those tasks.

In this way, the Scrum method improves on traditional project methods, which would begin by making a big roadmap for the project. The Scrum method takes a much simpler and straightforward approach by simply beginning on the most important tasks without a large, comprehensive plan.

Covey’s Time Management Matrix

In First Things First, Stephen Covey gives a framework for prioritizing tasks. The two things you should consider when choosing a task are importance and urgency. In the business sense, importance would be the amount of value a task brings to the project. Urgency deals with tasks that require immediate action. Covey suggests prioritizing importance over urgency, as unimportant but urgent tasks can be a huge waste of time. Important and urgent tasks are dangerous. You want to avoid being in the position of having to rush to finish something important. This is similar to Sutherland’s advice to tackle the most important tasks first.

Work in Sprints

A Sprint is the core process within Scrum. Sprints are fixed lengths of time, usually one or two weeks, in which the team works on a particular task or tasks. The key values of the Scrum framework are developed and maintained inside Sprints. Sprints are where the work gets done, where value is created, and where people turn ideas into reality.

(Shortform note: Sutherland and Ken Schwaber introduced the term “Sprint” in the essay “SCRUM Development Process,” which they first presented in 1995. Since then, the idea of working in Sprints has become ubiquitous in business management circles. Jake Knapp wrote a book on Sprints in 2016. We also see it show up in news articles that claim working in sprints will “transform your productivity,” and recommend working in short bursts even in your personal life.)

Sutherland gives us four phases to a Sprint cycle.

Phase 1: Plan

At this stage you should have a prioritized task list and a Scrum team ready to begin working. The goal of this phase is to determine three things:

- How the Sprint will bring value. The product manager begins by proposing how the product will increase in value during the upcoming Sprint.

- Which tasks will be completed in the Sprint. The team then chooses which items from the task list they will complete. The tasks must be fully completed within the chosen time frame, meeting the standards for completion defined in the task list.

- How the tasks will be completed by the Developers. The last step of Sprint planning is to plan out the work needed to complete the chosen tasks. This can be done by organizing the workload into daily tasks, but those decisions are left to the Developers. The Product Manager and Scrum Coach should have no say in how the tasks are completed.

Planning as a Habit

In The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen R. Covey gives advice on how to best prioritize your time and achieve your goals. When trying to tackle personal goals, he suggests weekly planning. Weekly planning is broad enough to allow for adjustment but narrow enough to ensure things are getting done. Covey gives a step-by-step guide to weekly planning:

Identify your roles

Identify one or two goals for each role

Assign a day for each goal

Schedule time for enriching activities

Build in time for the unexpected

Adapt the plan as needed

Covey’s advice thus aligns with Sutherlands: Covey recommends planning week-by-week because it can allow for frequent adjustment, and Sutherland recommends planning Sprint-by-Sprint for the same reason, to allow for frequent adjustment as the project proceeds.

Phase 2: Meet Daily

Sutherland recommends that during each Sprint, the Scrum Coach and Developers hold short meetings every day. He states these meetings should be held in the same place, at the same time, and they should be no longer than fifteen minutes. Consistency and simplicity are important.

During the meeting, each team member should report:

- What they accomplished yesterday.

- What they will accomplish today.

- What’s slowing them down.

This helps the team know exactly where they are in the Sprint, what needs to be done next, and where they can improve. In these daily meetings, there should be no additional tasks assigned by management. If there are any impediments to the team’s progress, it's the responsibility of the Scrum Coach to remove them. The Daily Meetings help build communication, clarify direction, and increase efficiency.

Use Multiple Lists to Increase Efficiency

The Scrum framework gives a team a structure to the workflow: Each week or two weeks, a Sprint is completed and each day, the team meets to discuss progress. Different task lists are used for each type of check-in. Sutherland isn’t the only management expert who recommends using different task lists for different purposes: In Eat That Frog, Brian Tracy recommends four different lists to use depending on which timeframe you need to plan for:

Master list: This contains everything you want to do. Any time a new idea or task comes up it's added to the master list.

Monthly list: At the end of each month, move items from your master list to your monthly list.

Weekly list: Build the weekly list as you work. This way, at the end of each week you will already have your next week roughly planned out.

Daily list: Take items from the weekly list and list the tasks you wish to complete that day. Check off items as they are completed.

Phase 3: Demonstrate

After each Sprint, the team must demonstrate what they’ve produced in the Sprint. Anyone with a stake in the project or its outcome is invited to see this demonstration. Outside participants, such as customers, are encouraged to attend and give feedback. If no stakeholders or customers are able to attend, the Product Manager acts as their stand-in and attempts to view the demonstration from an outside perspective.

The idea behind the Sprint demonstration is to force Developers into making a finished, demonstrable product during each Sprint. Sutherland recommends building a prototype—something you can show the customer that actually functions even if it’s not fully fleshed out, so that you don’t waste time trying to make a perfect product but instead focus on building something that works that you can improve later.

Prototyping

In Inspired, Marty Cagan discusses the usefulness of prototypes in software development. Prototypes take less time and energy to make than a finished product, and they allow the team to flesh out ideas and see what works. Cagan gives four types of prototypes:

Feasibility Prototype: A prototype used to determine if a product can actually be created. You should only build enough to ensure the team is capable of completing it.

User Prototype: A user prototype is a non-functional simulation of the final product. A simpler user prototype may be a bare-bones version to help the team visualize the product. A more complex user prototype may be tested internally and externally to see how it works.

Live-Data Prototype: A pared-down but functional version of the final product. A live-data prototype is used to test if a product is commercially viable by getting real data from test users.

Hybrid Prototype: This is a combination of the previous three types. These are the least scalable of the four types, as they are meant to be built quickly and provide feedback.

Phase 4: Reflect

After demonstrating the product, the team then examines the previous Sprint. The aim of the Reflection is to find ways to increase productivity and efficiency within the Sprint process. Team members should look at what went right, what went wrong, and how the team reacted to any obstacles or problems that arose. They should identify potential changes that could be made to improve the process. Then, they should decide which changes will have the biggest impact and look to implement them in the next Sprint. With each Sprint reflection, the team should be finding new ways to increase productivity.

This part of the process requires a high degree of maturity and trust, as each team member must take responsibility for their actions and look for ways to improve.

Accountability

The reflecting phase is about encouraging accountability: Whether working individually or with a team, you must hold yourself and others accountable if you wish to be successful. The Oz Principle details how to lose the victim mentality and assume responsibility for your actions. The authors lay out four steps to help practice accountability:

Face the facts: You must face reality if you wish to be accountable. This includes recognizing when things around you change, making space for other people’s perceptions, and being honest about your own shortcomings.

Admit your role: Acknowledge that you aren’t just a victim of circumstance and that your actions contributed to those circumstances. Once you recognize your own culpability, you can more easily find a solution.

Take responsibility for solving problems: If you see a problem, help fix it. It can be easy to say “not my job” or “not my fault,” but being accountable means helping to solve the problems you see around you.

Take action: Once you recognize a problem, you must stay committed to finding a solution. Don’t let any obstacles get in the way of your goal.

On top of individual accountability, The Oz Principle also examines how to be accountable as a team. A team’s accountability can have a direct effect on their creativity, camaraderie, and overall performance. Here are some ways you can nurture organizational accountability:

Recognize you and your team members are interdependent

Focus on results instead of individual responsibilities

Use rewards as a motivational tool

Encourage two-way feedback

Find the underlying causes of a problem

Shortform Introduction

The way the business world operates, according to Jeff Sutherland, is fundamentally flawed. In Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time, Jeff Sutherland explains the Scrum framework, a better management system than the traditional top-down approach. By using the carefully structured yet open-ended Scrum framework, a company, or any project team, can become much more efficient and productive.

About the Author

Jeff Sutherland is a software developer who co-created Scrum alongside fellow software developer Ken Schwaber. A former fighter pilot and Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Medical School, Sutherland has since helped dozens of businesses implement Scrum into their development process. He has been a CTO or CEO for eleven software companies, during which he developed Scrum into what it is today.

Connect with [Jeff Sutherland]:

The Book’s Publication

Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time was published by Currency, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, in 2014. Before Scrum, Jeff Sutherland co-wrote Software in 30 Days: How Agile Managers Beat the Odds, Delight Their Customers, and Leave Competitors in the Dust alongside Ken Schwaber. More recently, Sutherland released another book on the subject, A Scrum Book: The Spirit of the Game, which he co-wrote with James Coplien.

The Book’s Context

Historical Context

Sutherland wrote Scrum to explain and spread the ideas of Scrum to businesses outside the world of technology. Sutherland developed Scrum in the early 1990s with the help of Ken Schwaber and others. It was designed as a more effective way to develop software than traditional methods. Sutherland and Schwaber first presented Scrum at a research conference in 1995, and it has gained popularity ever since, especially in the technology industry. Tech giants such as Apple, Google, Facebook, Airbnb, Spotify, and Adobe use the Scrum framework in some capacity. Recently, the Scrum method has made its way into other industries, including education, construction, marketing, and finance.

Intellectual Context

Written well into Sutherland’s career as a product management expert, Scrum explains the Scrum framework, a subset of the agile business model, to the masses. Agile methodology is a system for product development that focuses on incremental progress and close collaboration. Sutherland, with sixteen others, released the Agile Manifesto for software development in 2001 and it has since exploded in popularity. There are hundreds of books and guides about the agile business model and how to implement it.

The Book’s Impact

Although Scrum didn’t sell particularly well, the ideas presented in the book have had a significant impact in the areas of business management and leadership and have influenced many more books on the subject. Another book, The Elements of Scrum, which was based on Sutherland’s ideas, is taught at colleges and universities across the United States. Since the publication of Scrum in 2014, the Scrum framework has garnered attention from business and leadership experts around the world.

The Book’s Strengths and Weaknesses

Critical Reception

Scrum was well-received among business experts but failed to gain enough attention to attract well-known book reviewers. Editorial reviews praise the book for its engaging and persuasive anecdotes and its easy-to-read explanations of the Scrum framework. User reviews, while generally agreeing that Scrum is helpful, seem to have more negative opinions on the overwhelming use of personal anecdotes. The stories, mostly taken from Sutherland’s experience creating and using Scrum, give readers a sense of the writer’s perceived self-importance, with one reviewer even accusing Sutherland of megalomania.

Commentary on the Book’s Approach

As the user reviews suggest, Scrum is highly anecdote-driven. The stories are often about failed businesses or companies Sutherland helped save with the Scrum framework. Within the stories, Sutherland does provide meaningful research backing up his ideas. Most of the research is based on psychology/sociology, or data-driven studies that exemplify the effectiveness of certain practices.

Commentary on the Book’s Organization

Scrum can be a bit redundant at times, as it goes over the same topics in slightly different ways. Also, readers would have benefited if the book had laid out what Scrum actually is much earlier. Instead, readers piece it together gradually as Sutherland jumps from story to idea to story.

Sutherland separates the book into nine chapters, each one tackling a different aspect of the Scrum framework. The first two chapters delve into the origins of Scrum and how traditional project management methods fail. The next few chapters contain the crux of his argument. They explain why Scrum works, with a small amount of information on how to use it dispersed throughout. The last few chapters look more deeply into how Scrum works, how it leads to happiness, and how it can change the world. Finally, the book ends with an appendix, which gives a brief description of the Scrum process and how to implement it.

Our Approach in This Guide

In this guide, we focus on the core principles of the Scrum framework. We’ve reorganized the nine chapters into an opening explanation of Scrum and six subsequent principles. We’ve also included commentary that supports some of Sutherland’s claims and provides actionable advice on how to implement certain strategies he recommends.

What Is Scrum?

Scrum is a framework made to help people and organizations efficiently solve complex problems with creative solutions. Scrum is designed to be simple, and it’s based on a simple idea: When working on a project, check in regularly to make sure you're heading in the right direction, and remove anything that might be slowing you down. The pillars of Scrum are incremental progress and adaptability rather than following a carefully prescribed plan. Applying the Scrum framework will help companies produce more value in less time by eliminating waste and maximizing time.

Jeff Sutherland is a software developer who created the Scrum method as a better way of developing products than the traditional methods. Published in 2014, Sutherland released Scrum almost twenty years after he first introduced the Scrum framework to the world in 1995. During this time, Sutherland refined and honed the Scrum method as he watched his ideas go from relative obscurity in the business world to the mainstream.

How the Scrum Framework Remains Adaptable

The Scrum framework emphasizes adaptability and as such, the framework itself is constantly evolving along with the rapidly changing worlds of business and technology. Sutherland, along with Scrum co-creator Ken Schwaber, regularly updates the Scrum Guide, which they first wrote in 2010. Sutherland and Schwaber last updated the Scrum Guide in November 2020, and they reiterate the idea that the Scrum framework’s simplicity allows it to be adapted and used across multiple fields and domains. Furthermore, this simplicity and adaptability allow the use of various processes and methods within the framework. For example, software company LinearB offers a free software tool that helps you further increase productivity, shorten development time, and increase employee fulfillment, building on the basic Scrum framework and adjusting it to suit their specific needs.

In this guide, we’ll take a look at the ideology behind Scrum and will examine how Scrum differs from the traditional management style. We’ll then explore in detail how Scrum works while examining why it works, as well as why it matters and why you should use it. Along the way, we’ll compare Sutherland’s ideas to other management experts and explore how they either align with or differ from other advice on business efficiency.

Agile Methodology

Scrum builds on the agile business model, which Sutherland, along with sixteen other software developers, released with the Agile Manifesto in 2001. The Agile Manifesto recommends four strategies for product development:

- Focus on people, not procedures: Focus on people instead of procedures, because the people, not the plans, are the ones doing the work.

- Build working products instead of extensive documentation: Focus on making something that works instead of detailing what a product is supposed to do.

- Work with the customers: Since the goal of a business is to provide value to the customer, give the customer a chance to provide feedback and base your decisions based on what they want.

- Respond to change instead of adhering to a plan: Requirements for a product will almost always change throughout the development process. Focus on adapting to a changing environment, no matter how late in development you are.

(Shortform note: The principles of the agile business model are ubiquitous in modern business theory. Business Model Generation, for example, provides nine strategy techniques to help create or optimize a business model, many of which echo the strategies set forth in the Agile Manifesto. One technique recommends collaborating with customers before designing a product or service. Another technique builds on the agile principle of adaptation, suggesting you imagine future environments to better prepare your business to adapt.)

Scrum is the framework Sutherland built to put these values into practice.

Scrum Ideology

Sutherland took the term Scrum from an essay on which he bases many of his ideas, “The New New Product Development Game,” by Japanese business writers Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka. Scrum, a rugby term, refers to the way a rugby team moves the ball down the field as a unit. An effective rugby squad works closely together with a clear goal in mind but numerous ways of achieving that goal. Like a rugby team, a Scrum team embraces creativity and unpredictability within a structured setting.

(Shortform note: Throughout Scrum, Sutherland uses sports stories and analogies to illustrate his points. Due to the hypercompetitive nature of the business world, it's common among businesses to use sports metaphors in daily language and to look to sports strategies to help the company succeed. Some experts argue that this us versus them mentality, though it can seem motivational, can actually be damaging to your company. In Understanding Michael Porter, Joan Magretta argues that a company should be more focused on providing a valuable service than beating the competition.)

The Scrum framework is founded on two key principles: Learn through observation and root out and eliminate waste.

Learn Through Observation

The Scrum framework works by a constant scrutiny of the development process. Sutherland mentions a concept he learned in the Air Force known as the OODA loop. Developed for aerial combat by Air Force Colonel John Boyd, OODA stands for observe-orient-decide-act. As it pertains to product development, you observe your situation, assess your options, make a decision, and then act on it. As you repeat this process, you can make better decisions based on the constant inflow of new information.

(Shortform note: Colonel John Boyd, a famous military strategist, developed the OODA loop in the mid-20th century. Though it was originally designed for military combat, it has since made its way into various fields such as business, sports, litigation, and law enforcement. The theory behind the OODA loop is relatively simple: if you can quickly and clearly see what is going on around you, you can put yourself in a position to make quicker, more effective decisions. In combat, it can be the difference between life or death. In business, a company that successfully uses the OODA loop can gain a massive competitive advantage.)

Eliminate Waste

Many of Sutherland’s ideas are based on businessman Taiichi Ohno’s Toyota Production System, which defines three types of waste commonly seen in traditional production systems.

Taiichi Ohno identified three types of waste in a work environment:

- Waste through inefficiency. This refers to activities or processes that cost more than they are worth. This can include overproduction, overprocessing, inefficient transportation, too much time spent waiting, and many others.

- Waste through unevenness. This is caused by inconsistencies in production or workflow. It can be caused by management’s failure to implement proper standards, or by employees failing to follow standards properly.

- Waste through overburden. This refers to waste caused by a team trying to meet unreasonable demands. You want to keep your team working hard, but giving them too much to do for no reason will cause burnout and mistakes.

The Scrum framework addresses this waste by finding and eliminating inefficiencies in the work process, developing a consistent rhythm to the workflow, and challenging the workers in a realistic way.

Ohno’s Seven Types of Waste and Just-in-Time Manufacturing

Ohno released his book, Toyota Production System, in 1978. Most of Scrum’s ideas on waste and inefficiency lead back to this book. Ohno, however, identified seven types of waste, not three. Ohno’s seven types of waste are delay, overproduction, overprocessing, transportation, unnecessary motion, excess inventory, and defects. These are all problems Scrum addresses, but Sutherland chooses to categorize them differently than Ohno.

Ohno’s theories on reducing waste have become a fundamental business strategy for many industries and have proven profitable. However, the philosophy is not without problems. Recently, the application of Ohno’s strategies on waste caused major problems in the supply chain. Derived from Ohno’s vision, just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing is a model that looks to minimize waste associated with overproduction. With JIT, manufacturers seek to meet demand without creating a surplus of product or raw materials. When Covid-19 upended expected supply and demand across the globe, JIT led to shortages in a wide variety of goods, further worsening the economic impact of the pandemic.

Scrum Versus a Traditional Management System

Within the Scrum framework, Sutherland advises that your team constantly inspect its methods and processes so that you can adapt to problems or changes in real time. This contrasts with a traditional project management style where you'd wait to finish a pre-planned stage and then review your results--by which time it's often a huge hassle or too late to fix issues.

(Shortform note: In general, it's good practice to assess your work as you're working on it. Waiting to review something until after it's complete can waste a lot of time and energy. This can be used in your daily life as well. Instead of waiting until the end of the month or end of the quarter to review your own performance, why not do it every day? One expert recommends you write down your daily routine and go over it to determine how to better spend your time.)

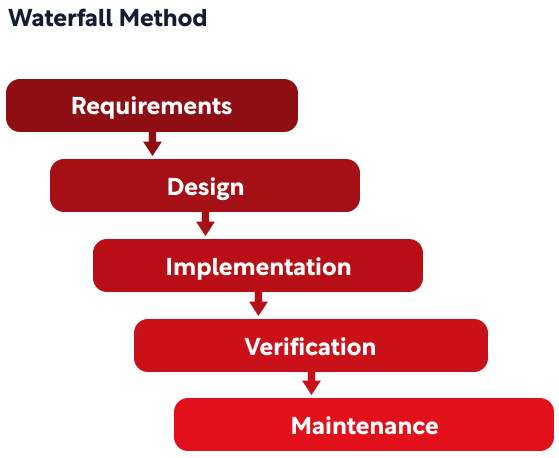

Sutherland argues that this traditional style, widely called the Waterfall Method, causes more problems than it solves. It relies on extensive planning and linear progression, which Sutherland claims is an inefficient way to manage a complex, creative project.

Waterfall Method Explained

To better understand why Scrum is so effective, it's important to understand the ways most American companies have operated since the beginning of the 20th Century. When planning a complex project, businesses generally used a comprehensive, step-by-step approach. Each part of the process is laid out in great detail, and each milestone has a specific deadline. Commonly known as the “Waterfall Method,” this meticulously structured planning can be depicted using a chart like this one:

Five Steps of the Waterfall Method

In Scrum, Sutherland gives a very sparse explanation of the Waterfall Method. It may be helpful to understand more about the traditional management system.

There are five stages in the Waterfall Method, and each phase is intended to be finished before moving on to the next.

Requirements: Here, you come up with the big picture ideas for the project. What problem are you addressing, what are you trying to build, and what needs to be done to build it? All the requirements should be collected and known from the beginning.

Design: In the design phase, you come up with the solutions to the problems set out in the requirement phase. Multiple design choices may be submitted.

Implementation: In this phase, you choose the design choice that you think will work best and build the product. Because you’ve done so much research beforehand, the implementation of your design should be fairly straightforward.

Verification or Testing: Here, you take the product and test whether or not it fits the requirements. If it does not, you go back and test to determine what the issues are.

Maintenance: Although the product meets the requirements, you still need to maintain quality after the product is released. This could involve further testing, updating, or enhancing of the product.

Problems With the Waterfall Method

Sutherland claims projects that use the Waterfall Method usually end up way behind schedule and way over budget. This isn’t the fault of the people involved, but with the system being used, which creates a myriad of issues.

Unrealistic Rigidity

When management tries to impose a precise method to accomplish a task, it fails to take into account how often things change and develop as you work on them. When you try to control a process down to the most minute detail, you leave the team with little room to adapt and reorganize.

(Shortform note: The human ability to adapt is one of our greatest strengths. Our capacity to share knowledge and create culture is what differentiates us from earlier ancestors and other primates. Because we have evolved to adapt to quickly changing environments, allowing for adaptation in the workplace is playing to our strengths.)

Waste of Time

One of the biggest problems of the Waterfall Method is the amount of time it takes to plan a complex undertaking. Since the plan is likely to change as you work on it, time that you spent creating the original plan ends up being wasted—all that time and effort could have been spent on more useful tasks.

(Shortform note: This is not to say that all planning is bad or a waste of time. You must have some kind of idea of what you’re doing and how you're going to do it. For example, the book Eat That Frog! says that one minute of planning can save up to ten minutes in implementation. The problem with the Waterfall Method is that it tries to plan everything ahead of time.)

Waste of Money

Another frequent misstep in project management is the tendency to throw money at a problem even after it’s clear that it’s not fixable. You’ve already invested all this time, effort, and money on this strategy, so why not spend even more time and money trying to fix it? This is the kind of thinking that leads to being chronically late and over budget.

(Shortform note: The tendency to continue with a plan that isn’t working is known as the sunk cost fallacy. Many projects fail because they spend too much money trying to rectify problems instead of changing course. Ryan Holiday, in Ego is the Enemy, recommends cutting your losses before it's too late.)

Micro-Management

The rigidity of a strict plan also leads to another undesirable consequence: micromanagement. Most people have experienced this: An overbearing boss or supervisor, whose attempts to control every aspect of work, ends up stifling employees. The Waterfall Method leads to micromanagement because the managers want to make sure everything is going exactly according to plan, so they look to exert more control over the entire process. Micromanagement is not only bad for employee morale, it causes a much more inefficient workplace.

(Shortform note: In The Leadership Challenge, James Kouzes and Barry Posner discuss the dangers of micromanaging from a leadership perspective. They argue that trust is a key factor in being a good leader, and micromanagement erodes trust between managers and employees. A good leader will trust her employees to get the job done without constant supervision. You can create a climate of trust by being the first to trust, showing empathy, and sharing knowledge.)

Lack of Inspiration and Creativity

Another aspect of productivity that traditional management fails to address is the importance of autonomy and creativity. When a team is told to follow a specific set of goals and also told exactly how to accomplish them, they’ll feel boxed in by the limitations. Instead of coming up with new ideas and solutions, workers find themselves stuck following the very guidelines that led to this rut in the first place. It can be a vicious cycle that’s hard to escape.

(Shortform note: Pixar co-founder Ed Catmull writes about the importance of creativity in Creativity, Inc. Catmull believed fostering a creative workplace helped set Pixar apart from competitors. He gives three tips for building a creative workplace: Promote candor, overcome fear, and embrace failure. These are all strategies that align with the Scrum method and differ from the Waterfall Method. Catmull also gives us eight tools to sustain creativity, which include promoting research, building learning opportunities, and experimentation.)

Communication Breakdown

While working on a complex endeavor, communication and clarity of direction are paramount. With the Waterfall Method, the separation of duties may lead to a lack of communication. Also, executives may try to increase productivity by increasing the size of their workforce. This causes more problems than it fixes: The larger the team, the harder it is to keep everyone on the same page.

(Shortform note: Experts say that in a modern, remote workforce, it's even more important for management to purposefully maintain open lines of communication with employees because remote workers don't engage in casual, "water cooler" chat which, in an in-person workspace, would allow for more natural communication. Furthermore, because communication is stretched thinner when working remotely, managers must make sure instructions and expectations are accurately communicated to employees.)

Benefits of the Waterfall Method

Although there are problems with the Waterfall Method, it does have potential advantages that Sutherland doesn’t mention. If you’re working on a straightforward project, one with a clear end-goal and clear steps to get there, it may be beneficial to lay it all out beforehand. A structured approach may allow for a more accurate budget estimate and make it easier to measure progress.

Also, if you need to add developers later in the project, it will be easier for them to get up to speed because of the vast amount of research done in the planning process.

Lastly, if you’re sure you’re building something that the customers or clients will want, it may be a waste of time to get constant feedback on every part of the development.

Overall, the Waterfall Method may work better for projects that lie at either end of the complexity spectrum: They’re either simple (making a ball pump) or potentially dangerous (building a rocket to take people to Mars). If you’re looking to make an air pump for inflating basketballs, you can be pretty sure what the customer wants: a small, light, functional tool. If you’re building a rocket, extensive research and planning will be necessary. When you know that any mistakes or oversights could lead to the loss of human life, it may be ok to sacrifice some efficiency in the name of safety. In other words, speed and efficiency aren’t always the answer.

Exercise: Examine Your Experience With the Waterfall Method

We’ve all probably used the Waterfall method at some point in our lives. As Sutherland says, it's an extremely common strategy that has been used for decades. How well has the Waterfall method worked in your experience?

Think of a time when you used the Waterfall Method, or something similar, to tackle a project. This could just be a simple project you did yourself or something you did with a team. When planning, did you include every task you needed to complete? Did you estimate how long each would take? How long did the planning process take?

Now think of the process of putting the plan into action. Did everything go according to plan? Did the project take more or less time than you expected? What things changed during the process? Which tasks were added and which were eliminated?

Looking back on the project, how would you have done things differently? Do you think extensive planning saved or increased time spent on the project?

Principle 1: Base Your Plan on Reality

One reason Sutherland says the Waterfall method doesn’t work is that it’s an exercise in unrealistic optimism: It’s hopeful to think that through careful planning you can know exactly how to do something and how much time, effort, and manpower it will take. Unfortunately, when that plan meets with reality, it almost always falls apart. With Scrum, Sutherland creates a framework based on the way humans actually work, taking into account what we struggle with and what we’re naturally good at.

What We’re Bad At

Under the right circumstances, people can do amazing things. We’re capable of complex thought and creative problem-solving that can change the world. In many ways, though, our brains are very limited. We simply aren’t able to do some things no matter how hard we try. It’s important to understand our limitations if we wish to achieve greatness.

(Shortform note: In the past century, work, school, and even daily life have grown increasingly complex, demanding more and more of our mental energies. Research suggests human intelligence may be leveling off. As our brains near their optimal capacity, we may have to use sources outside of our brains such as technology, our bodies, or physical space to supplement our limited mental capabilities.)

We’re Bad at Estimating Time

Humans are terrible at estimating how long something will take. When determining the amount of time a task will take, we can underestimate or overestimate by a factor of four. In other words, the task can take four times as long as expected, or a quarter of the time expected.

Why Humans Are Bad at Estimating Time

Sutherland says many times how bad people are at estimating, but doesn’t delve into why that is. Other experts have suggested some reasons:

Procrastination: Procrastination can add significant time to a project. Researchers suggest most procrastination comes from a fear of failure.

Bad Habits: When we perform any task, our brains tend to repeat how we did it whether it was done the right way or not. We often don’t consider how our bad habits will slow us down when estimating.

Planning Fallacy: People tend to be optimistic when planning things out. That is, we think we can perform tasks at a much faster rate than we actually can. Even when we know things usually take longer than we plan, this phenomenon still occurs.

Anchoring Bias: If we set an initial plan for completing a project, we become anchored to that plan even as it becomes clear it isn’t working properly.

We Don’t Speak Up

In a group setting, people also struggle with trusting their own judgment. Whether out of fear of looking unintelligent or misinformed, or a general sense that other people make sound decisions, the “bandwagon effect” causes people to go along with whatever decision the group makes. When making an important business decision, this can be a big problem. Half the group may think something is a bad idea but nobody says anything.

(Shortform note: The term “bandwagon effect” originated in politics, but its influence is prominent in the business and economics worlds. In some ways, it's helpful, as the popularity of a product can demonstrate its quality or usefulness. This can become a problem, though, when the popularity of a product isn’t aligned with quality. Effective marketing, combined with the bandwagon effect, may cause people to buy a product that they may not need or like.)

We Work Too Much

People who work too hard are less productive. Corporate culture often insists that employees work long hours in order to get as much done as possible. Sutherland argues that this has a negative impact on productivity, as it can lead to burnout and a demoralized workforce. In fact, he says that overworked employees actually get less done in more time. The ideal workweek is just under forty hours. If you work much more than that, your output will decrease.

(Shortform note: The effects of overworking and burnout are hugely detrimental. Overworking can lead to stress, sleep deprivation, and even death. In Japan, there is even a term for death by overwork: karoshi. Research suggests that this problem is spreading worldwide: An estimated 745,000 people died in 2016 from working too many hours.)

What We’re Good At

Just as crucial as understanding our limitations is understanding what we excel at. The Scrum method aims to help you work in ways that take advantage of how our brains function.

Comparative Sizing

People may be terrible at estimating time, but we are much better at comparing things. You may struggle to estimate how long it will take to mop the kitchen floor, but you know the living room is going to take much longer because it's a bigger room. Sutherland suggests using comparative sizing when estimating the difficulty of a task. Instead of estimating by time, estimate tasks by categorizing them into relative sizes. Our brains will be able to compute these estimations much more easily.

(Shortform note: Although it's difficult to know how long a project will take, executives and clients may still want an estimation. Robert C. Martin’s The Clean Coder provides three methods for estimating a project’s length. The Delphi method combines individual assessments to come to a group consensus. The Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) uses a formula that includes an optimistic, pessimistic, and most likely time estimate. Another method, derived from the law of large numbers, is to estimate in smaller chunks and add them up.)

Sharing Knowledge

Humans are social creatures. Our ability to communicate complex ideas and learn from each other are some of our greatest strengths. Sutherland understands this and recommends a work structure in which communication is fostered and knowledge is shared. Throughout a project, make sure to give employees the opportunity to exchange ideas and learn about things outside their specialties.

The Power of Sharing Knowledge

A work culture that enables and encourages employees to share knowledge is much more effective than one that doesn’t. Experts note six benefits of knowledge sharing:

Employees use each other’s best practices

Employees make quicker, better decisions

Knowledge doesn’t leave when an employee does

Decreases costs of outsourcing and third-party training

Employee-based training is more interactive and effective

Employees gain a sense of belonging

Understanding Narratives

People understand the world through stories. It’s how we contextualize information and comprehend difficult concepts. Therefore Sutherland advises that when planning a project, think about it like a story, not an abstract concept. Who are you building the product for? Why do they want it? How are they going to use it? If the entire team knows the story behind the project, and each task within it, they will work much more efficiently.

The Power of Storytelling

There are several psychological reasons storytelling is so powerful:

Our brains have evolved through narrative: Since the earliest days of recorded history, humans have used stories to understand the world in the forms of myth, tradition, and symbol. We use stories to create our identities, teach social values, and explain how things work.

Stories connect people and help us empathize: When we hear a story, we're able to see things from a different perspective. Our emotional response to narratives dictates most of our decisions.

Stories provide structure and meaning: The world is a lot more chaotic and random than we like to think. By imposing a narrative on the events in our lives, we give them an order we're better equipped to understand.

Principle 2: Build and Maintain an Effective Team

In modern businesses, Sutherland insists, too much emphasis is put on individual achievements, rather than the team’s accomplishments. But he argues that the team, not individuals, is creating a product, so it’s important to focus on collective performance. This holistic approach to management, emphasizing teamwork, is a pillar of the Scrum framework. Sutherland describes the three common characteristics of successful teams. He then explains the three roles within a Scrum team and the specific things they should do to create value.

Three Traits of Successful Teams

Sutherland gives us three common characteristics of effective teams:

Ambition

When creating a product, a team must aspire to be great. Without ambition, or what Sutherland calls transcendence, it’s impossible to achieve great things. Just the decision to strive toward a higher goal can be enough to rise above mediocrity. From a leadership perspective, it's vital to instill in your team a common objective and to explain why that objective is worth pursuing.

Sutherland says one way to inspire your team is to challenge them. Set lofty goals, ones worth achieving, and the team will have a strong sense of purpose.

Set Audacious Goals

In Built to Last, Jim Collins and Jerry I. Porras also argue that success follows ambition. To prove their case, they examine companies that set what they call “big, hairy, audacious goals,” or BHAGs. They argue that merely having a BHAG sets a company up for success because it helps to motivate its workforce.

They say that a BHAG should be clear, compelling, and challenging, and they should align with the philosophy of the company. They suggest ways to ensure the success of your BHAGs:

Fully commit to your goals: It’s not enough to merely set an audacious goal, the entire organization must be willing to get behind it.

Think beyond the profits: Although companies are profit-driven, a visionary company looks beyond the quarterly profits and aims to achieve something great.

Continue setting audacious goals: If a company manages to meet one of their goals, they must not stop there. A company that continues setting ambitious goals even after success are more likely to maintain that success.

Freedom

Once an objective is set, Sutherland says, let the team figure out how to achieve it. A team should organize and manage themselves and be empowered to make their own decisions. This freedom, or autonomy, leads to a happier and more effective team. If people feel they’re being constantly guided by management, it can be deflating. Not only does it rob them of their ambition, but it also stifles their creativity. Both of these can lead to a drastic reduction in productivity.

As a leader, you shouldn’t tell your team exactly what to do or how to do it. Rather, you should provide them with an objective and the necessary tools to complete it. Set expectations, then step back and let them work.

(Shortform note: A results-only work environment (ROWE) is a management strategy that allows for a great deal of freedom. In a ROWE, you measure and compensate employees by their output, or results, rather than the hours worked. Studies show that ROWEs can increase a company’s productivity, retention rate, and employee happiness. Best Buy, for example, implemented ROWEs in the early 2000s. Between 2005 and 2007, voluntary turnover dropped 90% while productivity increased 41%.)

Integrated Purpose

In a traditional business setting, one that uses the Waterfall model, there are usually separate teams assigned to each task. Once each task is completed, it's then handed off to the next team. This “handoff model” is slow and tedious, doesn’t allow for the quick correction of mistakes, and cultivates a culture in which communication between teams isn’t valued. For example, you might have a design team, a marketing team, a sales team, and a production team, all meant to stick to their own specific assignment.

Sutherland argues that the handoff model isn’t an effective way to work and that instead, your team should have integrated purpose, or what he calls cross-functionality. Team members should have various specialties but not a strict separation of duties. The team should be constantly feeding off each other’s skills. Collectively, the team should have all the tools and information necessary to complete the project, and they should be in a continual state of collaboration. This way, everyone on the team knows where they stand. If something changes, the whole team knows right away. If a problem occurs, the whole team works to fix it immediately.

(Shortform note: Experts caution that although teams should have some ability to take on each other’s roles, you should still allow for some specialization: When building a creative workplace, intellectual diversity is a key component. A team that is intellectually diverse has a wide range of experience, opinions, and perspectives. Teams with different perspectives and life experiences are better able to come up with creative solutions than teams whose members all think alike. With different backgrounds comes different ideas, and thus a more well-rounded, nuanced, and comprehensive approach to problem-solving.)

New Product Development

Sutherland focuses on three fundamental characteristics of effective teams, but in the essay he based many of his thinking on, “The New New Product Development Game,” Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka describe six characteristics of effective teams:

Built-in instability: Management gives the development team a broad strategy or goal at the beginning of a project. This should challenge the team while allowing the freedom to meet the challenges.

Self-organizing project teams: Discussed in detail above, a self-organizing project team is more creative and independent.

Overlapping development phases: A team is more likely to work as a unit if they don’t use the sequential approach of the Waterfall Method.

Multilearning: People involved in the project are constantly learning at the individual, team, and company level. Also, they learn things outside of their areas of expertise, acquiring a diverse knowledge and skill set.

Subtle control: Management, while allowing freedom, has enough control over the project to avoid too much risk or ambiguity.

Transfer of Learning: Knowledge is not only shared amongst the development team, it makes its way into other projects and other parts of the organization.

Although Sutherland only specifically names three common traits of successful teams, Takeuchi and Nonaka’s ideas are seen throughout the Scrum framework.

The Scrum Roles

Sutherland proposes three roles within a Scrum team:

- Product Manager

- Scrum Coach

- Developers

These are the only three roles in a Scrum team. They are each responsible for working together to create consistent value throughout the Scrum process.

Product Manager

The Product Manager (or what Sutherland calls the “Product Owner”) creates the overall vision for the product and makes sure the product is both viable and valuable. The Product Manager’s responsibilities include:

- Determining the goal of the project and what it should look like when it's finished

- Creating the task list of everything that needs to be done to complete the project

- Ordering the task list by the value it brings to the project

- Relaying feedback from the customers or stakeholders to the rest of the Scrum team

- Making changes to the project objective and the task list based on the feedback

The Product Manager is responsible for important decisions that will determine the success of the project. Her job is to convince the team of her decisions and make sure the work being done is bringing value.

(Shortform note: In Inspired, Marty Cagan agrees with Sutherland’s basic framework of having a product manager direct the vision of the project, oversee its task list, coordinate messaging to customers and stakeholders, and adjust the project as needed. Cagan differs in that he calls this person a project manager rather than a product manager, and he draws attention to the difference—this person oversees the work and the process, not the technical details of the product itself. Although Sutherland uses the word “product” in his title for this role, he views the role in the same way Cagan does.)

Scrum Coach

While the Product Manager is responsible for making the product valuable, the Scrum Coach is responsible for making sure the team is working as efficiently as possible. She coaches the team in the ways of Scrum and keeps the team working within the Scrum framework. The Scrum Coach does this by:

- Encouraging the team to self-organize and share knowledge

- Keeping the team focused on the current task

- Finding and removing any impediments to the team’s progress

The Scrum Coach meets with the team daily to make sure things are running smoothly. Like the Product Manager, she doesn’t assign specific tasks. She just ensures that communication is open and the team is making consistent progress.

(Shortform note: The 4 Disciplines of Execution discusses the way organizational coaches can help implement a company’s vision. An internal coach benefits an organization in three ways:

- They can quickly provide the team with the information or support they need.

- They can help the organization learn to be self-sufficient.

- They can quickly train new employees or leaders in the ways of the organization.)

Developers

The Developers are responsible for completing the items from the task list. They’re the ones building the product with guidance from the Product Manager and Scrum Coach. The Developers duties include:

- Estimating the relative size of each task

- Deciding how to complete the tasks within each Sprint

- Finishing each task completely before moving on to the next

Although the Scrum Coach makes sure everyone is working within the Scrum framework, the Developers must still hold each other accountable. Because the Scrum framework gives the Developers the freedom to work as they see fit, it's their responsibility to create consistent value within each Sprint.

Inspired Versus Scrum

In Inspired, Cagan discusses the importance of engineers to the Product Manager. The engineers, like Sutherland’s developers, are responsible for building the product. The engineers and the Product Manager should have a close, collaborative relationship in which they share ideas. The engineers will understand the product in more detail than the Product Manager, so they will be able to provide creative, realistic solutions to problems. This is similar to Sutherland’s ideas, in which the developers create the product while the Product Manager focuses on the big picture.

On top of the key positions, Cagan provides other roles that may be needed for product development, including marketing experts, researchers, analysts, and test engineers. Sutherland would probably be against these extra roles for two reasons: 1) All these duties should be performed by people on the original team and 2) the specialized roles would get in the way of collaboration. Instead, these people would just be part of the Developer team.

Why Small Teams Are More Effective

Although you want your team to be dynamic and diverse, that doesn’t mean bigger is better. In fact, Sutherland argues that the bigger your team, the less effective they become. Ideally, he says that a team should consist of five to nine members. Adding extra members to your team will generate more problems than it fixes because the human brain can only hold so much information. More team members add more lines of communication, and our brains can’t keep up.

Furthermore, adding people to a project that is behind schedule will only slow it down even more. One reason is that it takes time to bring people up to speed, especially if the project is well underway.

Malcolm Gladwell and the Power of Small Teams

In The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell argues that small groups have a stronger social influence than large groups. One reason for this is because of humans' limited emotional capacity. We’re only able to maintain meaningful relationships with a small number of people. In a business sense, this is why it's best to work in small teams. If you can actually have a relationship with every member of your team, you're more likely to work well together.

Gladwell shows that organizations work best when limited to 150 or fewer people. This is much larger than Sutherland’s suggested team size, but the idea behind it is similar. The human brain can only process so much information. Larger teams lead to less communication and more hierarchies, which can slow down progress.

Remove Specific Titles and Roles

Sutherland argues that one advantage of small teams is that you can more easily remove specialized roles and titles. He advises doing this because it will help communication flow more freely among team members. If each team member has a specific role or title, they tend to do things that only fit within that specialized role. Furthermore, they may be inclined to withhold their specialized knowledge in order to preserve the power they have within the team. Both of these lead to a less communicative, and thus, less effective team.

Transactive Memory

Transactive memory is the idea that people who spend time together develop a specialized division of labor. In other words, each member of the group becomes a specialist in certain areas, and they rely on each other to remember and retrieve that particular information. You see this occur in couples, where one person knows how to fix the shower and the other is responsible for making the grocery list. But transactive memory is also helpful in work settings, as it reduces the memory load for each person and allows the group access to more information.

Although Sutherland recommends removing specialized roles, this is done to promote transactive memory within a team. Because team members are working together closely, they are more likely to share information. Because they don’t have specialized roles, they are less likely to withhold information.

How to Fix the System

In a system that relies so heavily on teamwork, make sure you pay attention to how the team interacts and where team members tend to place blame when something goes wrong. When observing the mistakes or faults of others, it’s common to blame personality or disposition flaws rather than the situation. This phenomenon, called “Fundamental Attribution Error,” is common and can lead to disharmony, low morale, and arguments among teammates.

Sutherland claims that it’s not our inherent qualities but the system in which we work that dictates most of our actions. Instead of blaming individuals, the Scrum framework looks to find problems within the organizational structure and eliminate them. If there is something slowing the team down, it's up to the team to figure out why and find a solution. If there is a person struggling to complete a task on time, don’t complain to your coworkers or quietly grumble to yourself in the corner. Ask what the problem is. Offer to help them. Pointing fingers isn’t going to help the team get things done. Focus on fixing problems collectively.

Fundamental Attribution Error

The fundamental attribution error is a long-recognized psychological bias that can negatively affect our personal lives and relationships as well as our professional ones. Here are some tips on how to avoid it:

Find an honest reason: If you find yourself judging another too harshly, come up with a situational reason a mistake may have occurred. This will help eliminate any negative thoughts.

Remember the good things: Fundamental attribution error usually occurs because of a pre-existing negative opinion of someone. Try to remember the good qualities about someone to help quell those negative feelings.

Give the benefit of the doubt: In general, assume people mean well, especially on the first occurrence of a mistake. Be sure to consider the circumstances, though. If a mistake is potentially harmful to others, giving the benefit of the doubt can be dangerous.

Exercise: Reflect on Your Teamwork

Most of us use teamwork almost every day, whether it be at school, work, or home. Sutherland advises that team members should be allowed the freedom to choose their assignments and direct their actions and that teams should be kept small—no more than nine members. Reflect on some experiences you’ve had working with others.

Think of a team project you had to complete in which you weren’t allowed much freedom. Now think of another team project in which you and the other team members had more say in how to complete it. Which of these was more fun, challenging, and effective? Do you think a team can have too much freedom?

Have you ever worked on a team with over ten members? If so, how did it go? Was there a lack of communication amongst the team? Did you ever feel out of the loop? Did any in-groups form in which you felt left out?

Principle 3: Prioritize the Work

When starting a project, Sutherland says the first step is to develop the overall vision you have for your company: what problems you’re going to solve, what you’re going to make, how you’re going to make it. Once you know what you want to build, you must prioritize the things you need to do according to the value they bring to the project.

Assess What Tasks Are Needed and Rank Them

Sutherland says the first thing to do is to create a task list, or what he calls a “backlog”: a list of all the things that need to be done to make your vision a reality. The task list should include every possible task that might be needed for the end product.

Then, with the task list complete, go through the entire list and rank each item by importance. To do so, ask the following questions:

- What will have the biggest impact?

- What is most important to the customer?

- What will make the most money?

- What items are the easiest to complete?

Once you have a clear picture of which tasks will bring the most value in the least amount of time, begin working on those tasks.

Traditional project methods would take these tasks and make a big roadmap for completing the project. The Scrum method takes a much simpler and straightforward approach, by simply beginning on the most important tasks without a large, comprehensive plan.

Further, the Scrum method leaves room for adaptation, which is a key part of the Scrum framework. It’s important to remember that the task list is always subject to change. It’s rare, Sutherland claims, that what a team thinks is most important to the customer actually is. As your project develops, you may find it necessary to move items higher or lower on the task list, add or remove items from the list, or even change directions entirely if market conditions change drastically enough.

Covey’s Time Management Matrix

In First Things First, Stephen Covey gives a framework for prioritizing tasks. The two things you should consider when choosing a task are importance and urgency. In the business sense, importance would be the amount of value a task brings to the project. Urgency deals with tasks that require immediate action. Covey suggests prioritizing importance over urgency, as unimportant but urgent tasks can be a huge waste of time. Important and urgent tasks are dangerous. You want to avoid being in the position of having to rush to finish something important. This is similar to Sutherland’s advice to tackle the most important tasks first.

Clarify and Estimate the Task List

Before moving on to the Sprint, Sutherland says the Developers should go over the task list and answer three questions. These questions will help the team ensure that the tasks are clearly defined and achievable, while also giving them a reference point for the amount of work future endeavors will take.

- Is each task doable? The team should have all the information and tools they need to complete the task.

- How much effort will each task take? The Developers should estimate the amount of work every task will require. Later, they’ll use these estimates to determine how many tasks will be completed in a certain amount of time. Remember to base your estimates on relative size, not length of time.

- Is there a standard for completion? There should be clearly defined requirements for a task to be considered finished. Each completed task should provide tangible value to the project. It should be able to be demonstrated and, if possible, tested by customers or other outside sources.

How to Assign Tasks

Crucial Conversations gives advice on how to assign tasks once you’ve decided what you want to do. In a Scrum team, the Developers are in charge of task assignment. According to Crucial Conversations, assignments have four elements, which we’ll examine through the lens of a Scrum project:

Identify the tasks: The tasks will be provided to the team by the Product Manager. The Developers should make sure they know precisely what they are trying to accomplish.

Identify who’s responsible: Assign each task to an individual or group of individuals. In a Scrum project it should be clear which Developers are working on each assignment.

Set deadlines: The Scrum framework is against setting specific deadlines for the completion of the project, but it may be helpful and motivating to set smaller deadlines for individual tasks.

Decide how you’ll follow up: The standard for completion serves as a follow-up for each task, as it holds the team accountable for full completion of a task. This is the step that corresponds most closely to Sutherland’s advice to Developers—his advice to ask the three questions examining the tasks is a more detailed exploration of how a Developer would follow up.

Exercise: Make a Task List

See how much writing down your daily tasks can help your productivity. Then think about how using a task list changes when in a group.

Make a list of the things you need to do tomorrow and then order them by importance.

Now look over the list. Has simply writing the tasks down helped clarify what is most important? Do you think you will get more or less done if you make a list like this every day?

How do you think making a personal task list differs from making a list for a team? Will it be more or less helpful? Why do you think so?

Principle 4: Using Sprints

A Sprint is the core process within Scrum. Sprints are fixed lengths of time, usually one or two weeks, in which the team works on a particular task or tasks. The key values of the Scrum framework are developed and maintained inside Sprints. Sprints are where the work gets done, where value is created, and where people turn ideas into reality.

(Shortform note: Sutherland and Ken Schwaber introduced the term “Sprint” in the essay “SCRUM Development Process,” which they first presented in 1995. Since then, the idea of working in Sprints has become ubiquitous in business management circles. Jake Knapp wrote a book on Sprints in 2016. We also see it show up in news articles that claim working in sprints will “transform your productivity,” and recommend working in short bursts even in your personal life.)

Sutherland gives us four phases to a Sprint cycle.

Phase 1: Plan

At this stage you should have a prioritized task list and a Scrum team ready to begin working. The goal of this phase is to determine three things:

- How the Sprint will bring value. The product manager begins by proposing how the product will increase in value during the upcoming Sprint.

- Which tasks will be completed in the Sprint. The team then chooses which items from the task list they will complete. The tasks must be fully completed within the chosen time frame, meeting the standards for completion defined in the task list.

- How the tasks will be completed by the Developers. The last step of Sprint planning is to plan out the work needed to complete the chosen tasks. This can be done by organizing the workload into daily tasks, but those decisions are left to the Developers. The Product Manager and Scrum Coach should have no say in how the tasks are completed.

Planning as a Habit

In The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen R. Covey gives advice on how to best prioritize your time and achieve your goals. When trying to tackle personal goals, he suggests weekly planning. Weekly planning is broad enough to allow for adjustment but narrow enough to ensure things are getting done. Covey gives a step-by-step guide to weekly planning:

Identify your roles

Identify one or two goals for each role

Assign a day for each goal

Schedule time for enriching activities

Build in time for the unexpected

Adapt the plan as needed

Covey’s advice thus aligns with Sutherlands: Covey recommends weekly planning because it can allow for frequent adjustment, and Sutherland recommends planning each Sprint for the same reason, to allow for frequent adjustment as the project proceeds.

Phase 2: Meet Daily

Sutherland recommends that during each Sprint, the Scrum Coach and Developers hold short meetings every day. He states these meetings should be held in the same place, at the same time, and they should be no longer than fifteen minutes. Consistency and simplicity are important.

During the meeting, each team member should report:

- What they accomplished yesterday

- What they will accomplish today

- What’s slowing them down

This helps the team know exactly where they are in the Sprint, what needs to be done next, and where they can improve. In these daily meetings, there should be no additional tasks assigned by management. If there are any impediments to the team’s progress, it's the responsibility of the Scrum Coach to remove them. The Daily Meetings help build communication, clarify direction, and increase efficiency.

Use Multiple Lists to Increase Efficiency

The Scrum framework gives a team a structure to the workflow: Each week or two weeks, a Sprint is completed and each day, the team meets to discuss progress. Different task lists are used for each type of check-in. Sutherland isn’t the only management expert who recommends using different task lists for different purposes: In Eat That Frog, Brian Tracy recommends four different lists to use depending on which timeframe you need to plan for:

Master list: This contains everything you want to do. Any time a new idea or task comes up it's added to the master list.

Monthly list: At the end of each month, move items from your master list to your monthly list.

Weekly list: Build the weekly list as you work. This way, at the end of each week you will already have your next week roughly planned out.

Daily list: Take items from the weekly list and list the tasks you wish to complete that day. Check off items as they are completed.

Phase 3: Demonstrate

After each Sprint, the team must demonstrate what they’ve produced in the Sprint. Anyone with a stake in the project or its outcome is invited to see this demonstration. Outside participants, such as customers, are encouraged to attend and give feedback. If no stakeholders or customers are able to attend, the Product Manager acts as their stand-in and attempts to view the demonstration from an outside perspective.

The idea behind the Sprint demonstration is to force Developers into making a finished, demonstrable product during each Sprint. Sutherland recommends building a prototype—something you can show the customer that actually functions even if it’s not fully fleshed out, so that you don’t waste time trying to make a perfect product but instead focus on building something that works that you can improve later.

Prototyping

In Inspired, Marty Cagan discusses the usefulness of prototypes in software development. Prototypes take less time and energy to make than a finished product, and they allow the team to flesh out ideas and see what works. Cagan gives four types of prototypes:

Feasibility Prototype: A prototype used to determine if a product can actually be created. You should only build enough to ensure the team is capable of completing it.