1-Page Summary

Every day, we’re confronted with decisions small and large, whether it’s what to eat for breakfast or which career to pursue. Because our information is often messy and unclear, however, the right decision isn’t always obvious. According to Gabriel Weinberg and Lauren McCann, the remedy is mental models.

In Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models, Weinberg and McCann argue that mental models–concepts and patterns used to analyze various situations–provide the framework to optimize decisions amidst uncertainty. More generally, they argue that using these models can lead to super thinking, the ability to accurately understand the world.

Weinberg and McCann’s unique backgrounds are evident in different aspects of Super Thinking. As founder and CEO of DuckDuckGo, a search engine worth over $100 million, Weinberg brings business savvy to the book’s discussions of mental models for successful companies. As a well-published statistician who performed research for pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, McCann brings expertise to the book’s discussions of formal models for decision-making.

In this guide, we’ll proceed from general to specific uses of mental models. While Weinberg and McCann discuss more than 300 mental models, we’ve focused on a limited selection of some of the most useful models. First, we’ll discuss mental models more broadly in Part 1. Next, we’ll discuss mental models designed to avoid pitfalls in reasoning in Part 2, and mental models to use instead in Part 3. Finally, in Part 4 we’ll discuss mental models geared toward creating successful businesses. We’ll provide additional perspectives that expand on–and occasionally push back against–the mental models that Weinberg and McCann recommend.

Part 1 | Mental Models: What They Are and What They’re Good For

We’ll begin by explaining what mental models are, where they come from, and why they’re valuable in decision-making.

In short, mental models are concepts and patterns that help us understand various situations across distinct topics. For instance, the mental model of supply and demand dictates that the relation between supply and demand determines prices: If supply exceeds demand, the price decreases, and if demand exceeds supply, the price increases.

(Shortform note: In The Great Mental Models Volume 1, Shane Parrish and Rhiannon Beaubien describe mental models as representations of how things work. Weinberg and McCann, however, go further, using the term “mental models” to describe a wide array of concepts beyond mere representations of how things work. For example, they even refer to generic phenomena such as multitasking and organizational culture as mental models. For clarity, we’ve italicized the mental models included in this guide.)

Super Models and Super Thinking

Although mental models arise from a particular context, some mental models are useful outside of their original contexts. Weinberg and McCann call these super models, which are the focus of Super Thinking. By recognizing recurring patterns across disparate fields, super models provide a shortcut to superior reasoning.

For example, consider the concept of critical mass. In physics, critical mass refers to the mass of an atom at which a nuclear chain reaction becomes possible. Once an atom’s critical mass is reached, a chain reaction can occur, causing an explosion. Similarly, businesses reach critical mass when their customer base reaches a certain size, leading to explosive growth of the customer base. Dating apps, for instance, reach critical mass once they have enough members to establish a viable dating pool, because many new members join only after a sufficiently large dating pool exists.

Such models are useful, Weinberg and McCann argue, because they help you achieve super thinking—they provide you the means to more accurately understand the world and its underlying mechanisms. Super models eliminate misconceptions and inefficiencies in our reasoning, instead offering reliable patterns and heuristics to analyze various situations.

(Shortform note: In The Great Mental Models Volume 1, Shane Parrish and Rhiannon Beaubien argue that mental models can serve an even broader purpose: cultivating wisdom. Though it’s unclear what constitutes wisdom, Parrish and Beaubien claim that it involves the ability to see creative solutions to various problems. In this view, wisdom is practical–it helps us know what to do in the face of unexpected challenges.)

By improving our ability to evaluate information, super models improve our decision-making. When used in concert, disparate super models form a set of tools to inform our decisions in virtually any situation.

Part 2 | What to Avoid: Shoddy Reasoning and Unforeseen Consequences

To understand the general advantages of mental models, we’ll discuss mental models that help us avoid common pitfalls in decision-making. This discussion is two-fold: First, we’ll examine models that help us avoid shoddy reasoning, and second, we’ll examine models that help us avoid unintended consequences. By applying these models, we’ll make better-informed decisions whose consequences we understand.

Pitfall 1: Shoddy Reasoning

Weinberg and McCann assert that, when reasoning, we naturally defer to conventional thinking and our intuition, which is our ability to reason subconsciously. However, conventional thinking and intuition are shaped by inflexible assumptions, which means they can be rigid. For example, the practice of bloodletting–withdrawing someone’s blood for medicinal purposes–was part of conventional medical practice because it fit neatly with Humorism, the theory that we’re composed of four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile). Since Humorism was an entrenched assumption, it led to a rigid belief in the efficacy of bloodletting for roughly 3,000 years until the practice was largely discredited in the late 1800s.

(Shortform note: In Freakonomics, Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner argue that we defer to conventional thinking because it’s convenient and allows us to avoid the complexity of the real world. Because conventional thinking is typically founded upon anecdotes, rather than quantitative data, it results in misconceptions. Consequently, they argue, appealing to conventional wisdom often leads us away from truth.)

In light of this rigidity, conventional thinking and intuition can mislead us in situations where they’re inappropriate. For instance, in the case of bloodletting, the conventional assumptions of Humorism misled physicians into harming their patients. In this section, we’ll examine such situations so we know when to avoid this type of reasoning.

Inappropriate Intuition

To determine whether intuition is inappropriate, Weinberg and McCann use Daniel Kahneman’s model of fast and slow thinking, outlined in Thinking, Fast and Slow. Kahneman distinguishes between fast thinking, where our mind operates quickly and involuntarily (as in doing basic math), and slow thinking, where we reason carefully and deliberately (as in doing calculus).

They argue that we should avoid leaning on intuition in situations suited for slow thinking. For instance, imagine that you’re an American visiting a less-talkative culture, and none of the locals are willing to talk with you. If you rely on intuition, you might incorrectly conclude they’re impolite or rude, when there are simply different norms at play. In this case, use slow thinking to consider these unfamiliar norms instead of making a snap judgment.

(Shortform note: One reason intuition leads us astray in these situations is its tendency to perceive patterns and connections between events, even when there are none. One example of this is gambler’s fallacy, the belief that incidental patterns that happened in the past will hold true in the future. For example, when playing roulette, gambler’s fallacy might cause us to believe that the ball is more likely to land on red if it’s landed on black multiple times in a row. At an extreme, our intuition can lead us to embrace beliefs we know are false; in one study, subjects intuitively held beliefs about probabilities that they knew to be false.)

Reason From First Principles

In situations that call for slow thinking, a more helpful mental model is reasoning from first principles. McCann and Weinberg explain that first principles are self-evident assumptions that ground your reasoning. For example, in deciding which career path to pursue, you might follow the first principle that upward mobility is valuable.

(Shortform note: Reasoning from a foundation of self-evident assumptions isn’t a novel idea—René Descartes proposed a similar approach, called foundationalism, in his Meditations on First Philosophy. However, many have rejected the notion of self-evident assumptions as illusory. For example, Euclidean geometry rests on the seemingly self-evident assumption that two parallel lines never intersect. But even this assumption has been rejected—mathematicians like Carl Gauss have constructed coherent systems which deny this “parallel postulate.” So, it’s best to treat even self-evident assumptions with skepticism.)

First principles provide a sturdy foundation for our beliefs, helping us avoid the shortcomings of conventional thinking. Because the assumptions underlying conventional thinking are often misguided, using first principles can help us avoid them. For example, conventional astronomy once placed the Earth at the center of the solar system. However, Copernicus rejected this conventional view because he accepted the first principle that the most logical mathematical model of stars’ movements was correct. Since the heliocentric model was the best mathematical model of the stars, Copernicus accepted it instead.

(Shortform note: Because our conventional beliefs are ingrained, the unconventional beliefs derived from first principles often draw social backlash. Galileo, for example, was branded a heretic by the Roman Catholic Church and sentenced to life-long house-arrest for accepting the Copernican view that the Earth revolved around the Sun.)

De-Risk Assumptions

Still, even seemingly self-evident assumptions can be mistaken. To avoid false assumptions infiltrating your reasoning, Weinberg and McCann recommend another mental model: De-risk your assumptions by testing their validity with objective measures.

This de-risking process can look different depending on the assumption. For instance, a conservative political candidate might assume they’ll comfortably win historically Republican districts. In this case, de-risking might involve conducting a poll to test this assumption.

(Shortform note: De-risking works well for empirical assumptions, but it’s less practical for value judgments. For instance, Weinberg’s company, DuckDuckGo, assumes that promoting internet privacy is valuable. To take another example, PETA assumes that speciesism—the view that certain species are inherently superior—is wrong. It’s unclear how to de-risk either of these assumptions—we can’t run experiments to determine the truth of speciesism or the value of privacy. When your assumptions can’t be de-risked, it’s best to proceed with caution.)

Account for Your Frame of Reference

False assumptions aren’t only a risk when reasoning from first principles—we’re also susceptible to false assumptions rooted in our own perspective.

For example, consider a model from Einstein’s theory of relativity, the frame of reference. In physics, an object’s frame of reference is roughly its location relative to which its speed and direction can be measured. To oversimplify, we could say that relative to our location inside a moving airplane, we’re currently stationary, though relative to the location of the airport, we’re currently traveling north at 550 mph.

We all have our own personal frames of reference, our subjective experience through which we perceive the world. To reason objectively, we need to keep in mind our own frame of reference and the biases afflicting it. Weinberg and McCann caution that one factor impacting our frame of reference is availability bias, where we overemphasize recently acquired information. For instance, a news report about recent shark attacks might make us think they’re a major issue, when they actually only cause about one fatality every other year.

Exploiting Your Frame of Reference to Influence Your Decisions

In Nudge, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein argue that policymakers and businesses should exploit biases in our frame of reference to “nudge” us toward better decisions. They suggest techniques including:

Narrowing our available decisions—for example, payment menus might offer only three possible tip options.

Implementing default decisions—for example, subscriptions might offer a free trial period, then default to charging you once the trial ends.

Offering clear incentives—for example, Germany pays you for each bottle you recycle.

Although Thaler and Sunstein encourage nudging consumers to make better decisions, beware of organizations that attempt to nudge you toward undesirable decisions. For instance, some businesses use payment prompts to nudge you toward “guilt tipping,” where you tip an unreasonably high amount. By only listing exorbitant tip options, these businesses exploit your availability bias to your detriment.

Fundamental Attribution Error

Another issue caused by our frame of reference is the fundamental attribution error, where we misattribute the motivations of others to character or personality, rather than external factors. For example, if we thought our server was being cold, we might conclude that they’re rude and impolite, not that they’ve just had a bad day.

To combat this error, Weinberg and McCann encourage seeking out the most respectful interpretation of others’ behaviors. Essentially, this involves viewing others’ actions charitably, rather than cynically. This advice squares well with Hanlon’s Razor, a mental model stating that we shouldn’t attribute someone’s behavior to malice if we can instead attribute it to carelessness.

(Shortform note: Hanlon’s Razor is only meant to be a general heuristic. As such, it can lead us astray in situations where malice is a better explanation than carelessness, even if both offer possible explanations. In Pride and Prejudice, Jane Bennett exemplifies the danger of misusing Hanlon’s Razor: When Caroline Bingley repeatedly tries to sabotage Jane’s budding relationship with her brother, Jane repeatedly—and implausibly—gives Caroline the benefit of the doubt.)

Pitfall 2: Undesired Consequences

Now that we’ve seen how to avoid shoddy reasoning, we’ll learn how to avoid harmful consequences by improving our predictions about the future. To do so, we’ll learn several mental models that illuminate the inadvertent consequences of our actions.

Inadvertently Harming Your Neighbor

The first unintended outcome Weinberg and McCann discuss results from the tyranny of small decisions, where individually reasonable decisions collectively create a worse outcome for everyone. For instance, you might think your vote doesn’t matter and therefore refrain from voting. While this seems reasonable, democracy would crumble if everyone followed suit.

The tyranny of small decisions is especially prevalent regarding public goods, since it’s tempting to think that it won’t matter if we take more than our rightful share. However, public goods can be jeopardized if everyone follows suit, illustrating another mental model: the tragedy of the commons. For instance, during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, people flocked to stores to buy excessive amounts of groceries. This created shortages, leaving many without access to vital items.

Kant’s Antidote to the Tyranny of Small Decisions

In his Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, Immanuel Kant recognized that decisions that seem individually reasonable can lead to collective catastrophe if everyone makes them. Consequently, he argued that for an individual decision to be rational, it must be universalizable: you can rationally wish that anyone in the same context could make the same decision. So, for example, lying is normally irrational, because the trust that underlies our communication would be destroyed if everyone constantly lied.

Accordingly, consulting Kant’s universalizability maxim can help prevent the tyranny of small decisions and the tragedy of the commons. If we ask, “Would it be rational to want everyone to make the decision I’m contemplating?” we can better determine which decisions might lead to collective disaster. In practice, this can help us understand why we should normally vote, tell the truth, and conserve public goods, to list a few.

Failure to Think Long-Term

In a similar vein, some decisions yield benefits in the short term while leading to long-term disaster. To illustrate, consider the mental model based on the boiling frog, which stays in a pot of water as the temperature gradually increases, eventually finding itself boiled alive. Although the increase in temperature feels nice in the short term, it creates a long-term catastrophe.

Weinberg and McCann argue that we’re susceptible to such decisions because of short-termism. In finance, this refers to emphasizing short-term results to the detriment of long-term results. For instance, a company that only focuses on marketing current products might fail to develop new products necessary for future success. Weinberg and McCann suggest that short-termism afflicts our general decision-making as well.

(Shortform note: Certain cultures are more oriented around short-term progress than others, indicating a cultural basis for short-termism. The United States, for example, is especially susceptible to short-termism. East Asian countries, by contrast, are typically inclined toward long-term thinking.)

To combat short-termism, heed the precautionary principle and act with extreme caution when an action’s potentially harmful consequences are unknown. More concretely, this involves analyzing potential risk by considering the harmful consequences that an action could lead to. Ask yourself, “Is there reason to think that this action has dangerous consequences?” If the answer is “yes,” pause before acting. By adhering to this principle, Weinberg and McCann suggest we’re less likely to run into harmful consequences down the road.

Pushback Against the Precautionary Principle

Although the precautionary principle seems intuitive, legal scholars have argued that it has untenable consequences. In particular, when all possible decisions have potentially harmful consequences, the precautionary principle ends in stalemate. For instance, critics of nuclear power object to its potentially catastrophic consequences, while the alternative—fossil fuels—might lead to devastating climate change. The precautionary principle offers little help in such situations.

More generally, these situations illustrate conflict between the precautionary principle and expected-utility theory, the view that the rational decision in a given context maximizes utility—in short, it yields the highest net benefit, on average. Because high-risk decisions sometimes have sufficiently high rewards, expected-utility theory might recommend making such decisions where the precautionary principle counsels caution. For example, the possibly vast rewards of transitioning to nuclear energy could justify our doing so, in spite of the risks.

To reconcile these decision-making principles, some have argued that the precautionary principle is simply a helpful heuristic to use in practice, not a foolproof law of decision theory. In other words, the precautionary principle is a useful guideline, despite being theoretically questionable.

Part 3 | What to Do Instead: Make Efficient, Well-Informed Decisions

At this point, we have a good grasp of what to avoid when making decisions. Now, we’ll turn to mental models demonstrating what to do instead.

First, we’ll examine the general fundamentals of decision-making, exploring an array of mental models for increasingly complex situations. Afterward, we’ll explore ways to make decisions efficiently, since making the best decision is pointless if it takes an impractical amount of time.

Fundamentals of Decision-Making

Weinberg and McCann assert that decision-making is difficult because nobody has access to perfectly accurate, comprehensive sources of information. Rather, our information is often messy and flawed, so we can’t always predict how our decisions will pan out. In this section, we’ll explore decision-making models to recommend the best choice based on the complexity of the decision.

Least Complexity: Pro-Con List

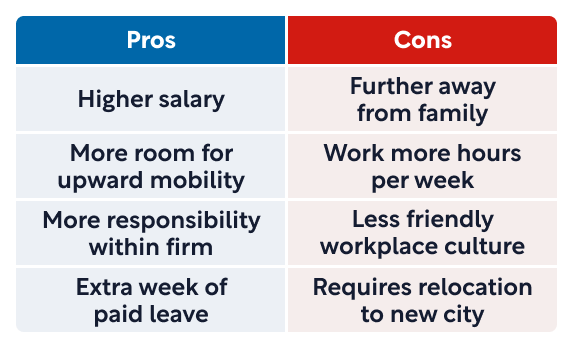

First, let’s look at the best-known decision-making tool: the pro-con list, which sorts the pros and cons of a decision in parallel columns, making it easier to see the positive and negative consequences. For instance, imagine you’re a lawyer deciding whether to accept a higher-paying position that would require moving away from your family. In this situation, you could draft the following pro-con list of accepting the position:

Popularity notwithstanding, Weinberg and McCann argue that the pro-con list has several flaws:

1. It creates a false dichotomy, since many consequences don’t fit neatly as pros or cons.

(Shortform note: The false dichotomy created by pro-con lists is an example of narrow framing, where we constrain our perceptions of outcomes by forcing them into imperfect categories. This narrow framing distorts our perception by casting outcomes as black and white, causing us to ignore nuance and subtleties that might be crucial to our decision.)

2. It fails to weight different pros and cons, so you focus solely on the quantity of pros and cons.

(Shortform note: To mitigate this problem, consider dividing pros and cons into major and minor subcategories. For example, more room for upward mobility could be a major pro, whereas an extra week of paid leave might only be a minor pro.)

3. The grass-is-greener mentality leads us to naturally overemphasize pros. (Shortform note: While the grass-is-greener mentality inclines us toward decisions that require change, status quo bias—the preference for our current situation over alternatives—inclines us against making decisions which involve substantial change. In such cases, we may be naturally predisposed to overemphasize the cons of change, rather than pros.)

So, while a pro-con list may work well enough for simpler decisions, Weinberg and McCann caution against using it in more complex decisions.

More Complexity: Cost-Benefit Analysis

To improve, Weinberg and McCann recommend creating a cost-benefit analysis of your decision. Unlike pro-con lists, a cost-benefit analysis lists the cumulative costs that a decision will incur alongside its cumulative benefits. It thus quantifies the consequences of your decision.

At a rudimentary level, a cost-benefit analysis might weigh individual pros and cons on a scale of 10 to -10, summing these values to recommend a decision—if the total is positive, the decision is worthwhile, and if it’s negative, the cost is too high. Returning to our pro-con list above, you might retool it into the following cost-benefit analysis:

Unlike the pro-con list, the cost-benefit analysis yields a more conclusive verdict: You shouldn’t take the new position, since the cons outweigh the pros.

To further improve your analysis, Weinberg and McCann recommend assigning each cost and benefit an explicit monetary value. For instance, relocating to a new city might cost $10,000, whereas an extra week of paid leave might be worth $3,000.

(Shortform note: While assigning costs and benefits a monetary value can be helpful, remember that monetary value diminishes beyond a certain point. For example, if you currently make $40,000 a year, a $15,000 raise could tangibly improve your quality of life. However, if you’re currently making $250,000, it’s unlikely that a $15,000 raise would have the same impact. So, be sure to consider these diminishing returns alongside your cost-benefit analysis.)

Most Complexity: Decision Trees

Both the pro-con list and the cost-benefit analysis assume that you’ll know what will result from your decision. But Weinberg and McCann recognize that sometimes, there are many possible outcomes, and you have only a rough idea how likely any given outcome is. For instance, when governments institute new policies, they rarely know the exact consequences beforehand.

In such cases, use a decision tree to handle this uncertainty. In addition to assigning monetary values, decision trees also assign probabilities to each outcome, representing the likelihood that it will occur.

To see this in action, let’s continue the lawyer example with a few caveats: First, if you accept the new position, there’s an 80% chance that you’ll thrive and eventually become a partner. Second, the increased pressure might make you crack, so there’s a 20% chance that you’ll end up getting fired at the new job. Finally, you’re 100% certain that staying at your current job will lock you into your current position—an associate—for the foreseeable future.

Here, there are three possibilities: You accept the new job and become a partner, you accept the new job and crack under pressure, or you stay at your current job and remain an associate. Assuming you’ve assigned these three outcomes values of $100,000, -$50,000, and $75,000, respectively, you can create the following decision tree:

This decision tree lists possible decisions in the first node (rectangles), the likelihood of a given outcome in the second node (ovals), and the monetary value of that outcome in the third node (diamonds).

Crucially, decision trees allow us to calculate each decision’s expected value, the average monetary value resulting from a decision. To do so, multiply the likelihood of each outcome by its respective monetary value, and then sum them up for each decision. If your decision has two possible outcomes, your calculation would look like this:

(Outcome 1 likelihood)x(Outcome 1 monetary value) + (Outcome 2 likelihood)x(Outcome 2 monetary value) = (expected value)

For example, you’d calculate the expected value of accepting the new job with this formula:

(0.8)x($100,000) + (0.2)x(-$50,000) = $70,000

By contrast, the expected value of keeping your current job is more straightforward:

(1)x($75,000) = $75,000

Because the expected value of keeping your current job is higher than that of accepting the new job, the decision tree recommends keeping your current job.

Does Deliberation Yield More Satisfying Decisions?

The decision-making tools Weinberg and McCann discuss all assume that deliberation leads us to make better decisions. However, this assumption might be false; one recent set of studies showed that, even for complex decisions, people were generally more satisfied with decisions made without deliberation. For example, among customers shopping for complex products at IKEA, those who purchased products without deliberating were more satisfied than those who purchased products after deliberating.

One possible explanation for these results is that customers who deliberate before making decisions have higher expectations, making them harder to satisfy. It’s possible that conscious deliberation still leads to better decisions, even if it doesn’t lead to more satisfying decisions. Consequently, this allows us to reconcile the studies’ results with Weinberg and McCann’s assumption that deliberation helps us make better decisions.

Efficient Decision-Making

So far, we’ve learned how to make decisions amid uncertainty. Now, we’ll focus on making decisions efficiently. To do so, Weinberg and McCann discuss mental models designed to maximize our efficiency. We’ll examine three:

1. Before approaching specific decisions, identify your north star, your overarching goal or vision. When you orient decisions toward your north star, your abilities compound and you become more efficient at pursuing your goals.

(Shortform note: Weinberg and McCann don’t offer actionable advice for finding your north star. However, Simon Sinek’s Start With Why provides a strategy: Step back and reflect on your motivations for your actions. This might involve asking, “What do I particularly enjoy about my job?” For example, if you own a bakery, you reflect and realize that baking serves your larger goal—bringing your community together in a warm environment.)

2. After identifying your north star, perform deep work, a concept from Cal Newport’s book, Deep Work. This involves spending extended periods of time dedicated to one important task, free of distractions and interruptions. In the long run, performing deep work will yield greater returns than juggling various tasks at once.

(Shortform note: Weinberg and McCann discuss deep work as an alternative to multitasking, which diffuses your concentration across various activities. However, Newport clarifies that deep work is also an alternative to task-switching, where you frequently shift gears from one task to another. Because mental residue from the previous task takes several minutes to overcome, Newport argues that task-switching also inhibits efficiency.)

3. Perform high-leverage activities to get more out of your decisions. In physics, a lever allows you to lift heavier objects than you could on your own. Similarly, high-leverage decisions create oversized results from less effort.

(Shortform note: In certain contexts, the term “leverage” has a negative connotation, as it involves exploiting an advantage to get what you want. For example, a corrupt politician might leverage their influence to get unpopular bills passed. Alternatively, in The Great Mental Models Volume 2, Shane Parrish and Rhiannon Beaubien argue that leverage can be an extension of reciprocity. In other words, leverage allows you to offer others the best exchange for your services, which benefits all parties.)

Part 4 | Professional Uses: Decisions for Successful Companies

So far, we’ve focused on general principles of decision-making, with an eye toward pitfalls to avoid and models to apply instead. In Part 4, we’ll explore more specific uses of mental models, focusing on professional uses for business leaders.

First, we’ll examine mental models to understand general strategies for building successful companies and business models. Next, we’ll focus on building successful teams and helping your employees reach their potential. Then, we’ll examine mental models geared toward increasing and retaining your market power. Finally, we’ll conclude by discussing mental models designed to avoid, or minimize, conflict with competitors.

Use Natural Models to Become Adaptable

In evolutionary theory, the process driving evolution is natural selection. Broadly speaking, natural selection dictates that genes which contribute to genetic fitness—the ability to survive and reproduce—are most likely to be passed down. For example, giraffes with longer necks can reach food more easily than those with shorter necks, which improves their odds of surviving and reproducing. In turn, that trait is more likely to be passed down to future generations.

Weinberg and McCann argue that natural selection likewise applies to societal contexts, as ideas that adapt to society’s evolving preferences are more likely to thrive. Businesses that adapt to these shifting preferences are better positioned for success, while those unwilling to adapt are quickly left behind. Weinberg and McCann provide a variety of mental models to help maximize adaptability and put your business on the path to success.

Adaptation as an Infinite Game

By constantly adapting to a dynamic society, you treat business as an infinite game–like Tetris–where the objective is to continue playing indefinitely. In doing so, Simon Sinek argues that you’ll be more successful than if you view business as a finite game—like chess—that has a fixed endpoint. To treat business as an infinite game you adapt to, Sinek encourages the following:

Be prepared to pivot proactively. By anticipating changing societal preferences, you can position yourself to thrive when change does occur.

Study worthy competitors. By studying successful competitors’ strategies, you can learn additional ways to adapt and survive.

Build trusting teams. If you cultivate trust, your employees are more likely to discuss ideas for improving your company.

Overcome Inertia

A primary obstacle to adapting is inertia. In physics, inertia refers to an object’s tendency to continue along the same path in the absence of external forces. For example, if you’re playing billiards and shoot the eight ball toward the corner pocket, it will continue in that direction unless an external force acts upon it.

Similarly, Weinberg and McCann argue that personal and professional inertia makes us resistant to changing our current path, which creates harmful rigidity. To avoid this rigidity, we must constantly question our beliefs and assumptions, and be willing to experiment with change. Netflix exemplifies the value of resisting inertia—in 2007, they shifted from physical DVD rentals to online streaming, upending the entertainment industry.

(Shortform note: In The Great Mental Models Volume 2, Parrish and Beaubien discuss a closely related physics model: friction, a force that hinders motion. In a business context, external factors can create friction and hinder adaptation. For example, computer companies might encounter friction via hardware manufacturing issues, and start-ups might encounter friction in the form of funding issues. When working in concert, friction and inertia can lead to stagnation: Because of inertia, entities that are currently stationary tend to stay stationary, and because of friction, external factors make it difficult to change paths.)

Create Momentum

Closely related to inertia is momentum. To succeed as a business, Weinberg and McCann propose pursuing ideas and products whose momentum is increasing.

To identify ideas and products with increasing momentum, seek out those about to reach a tipping point. In short, a tipping point is the moment when a system begins to rapidly shift. For example, in the 1990s, Baltimore reached a tipping point that sparked a syphilis epidemic, as a large number of those in high-density areas were exposed.

In business, tipping points occur when products are purchased not only by early adopters—those willing to try new ideas without social pressure—but also by the early majority—those willing to try ideas popularized by early adopters. By remaining aware of trends among early adopters, you can anticipate which products are likely to gain momentum in the future.

How to Reach the Tipping Point

Among your own products, you need to reach tipping points to maximize momentum. In Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey Moore provides a guideline for helping you reach tipping points by crossing the “chasm” between the early and mainstream market. This guideline includes four steps:

Use your intuition to choose a niche market to target.

Develop a “simplified whole product” for your niche—roughly, this is your core product and necessary external components. For example, a simplified whole product of a smartphone would include the phone and its operating system and charging devices.

Position your product by developing a position statement that situates it among competitors in the market.

Secure a distribution channel to sell your product to potential customers.

For example, imagine you want to create a dating app. First, you might intuitively see the potential for a dating app for divorcees, and choose them as your niche market. Next, you could develop a beta version of your website ready for a smaller pool of members. After that, you could position your product as a viable alternative to the competition, highlighting its advantages. Finally, you could purchase advertisements located in places most viewed by divorcees.

Harness Your Team’s Potential

Still, Weinberg and McCann recognize that adaptability alone isn’t sufficient for success—you also have to harness your employees’ potential to build thriving teams.

In particular, Weinberg and McCann’s goal is to build 10x teams, those composed of competent employees positioned to thrive in light of their unique skills. To build these teams, they argue that one obvious strategy—recruiting only all-star employees—won’t work, because Joy’s Law states that most of the smartest, highly talented people in the world always work for someone else. Since you can’t bank on everyone being a natural all-star, it’s crucial to instead harness your employees’ potential.

(Shortform note: Even when they’re available, star employees can create challenges in your team. For example, hiring a star can result in more interpersonal conflict—possibly owing to jealousy and resentment—which hurts productivity. In a similar vein, providing too much positive feedback to your star can feed their ego and harm team performance. So, star employees aren’t always worth the trouble.)

Organizational Culture

The first step toward building 10x teams is creating a strong organizational culture. In short, organizational culture refers to the shared beliefs, practices, and values of a given organization.

Weinberg and McCann clarify that strong organizational culture isn’t one-size-fits-all. Still, certain steps are essential to shaping a positive culture, including:

- Designate a concrete north star.

- Make your core values explicit.

- Reward employees for outstanding performances.

- Embody your desired norms and values.

By taking these steps, leaders can actively shape company culture in the desired direction.

More Ways to Improve Organizational Culture

While Weinberg and McCann view organizational culture as only one component of thriving businesses, Patrick Lencioni argues that it’s the single biggest advantage a business can attain. In The Advantage, Lencioni offers several recommendations for improving organizational culture to supplement Weinberg and McCann’s strategies:

Encourage healthy debate among the leadership team, allowing members to determine the best idea on its merits.

Foster accountability among team members. This decreases the burden on leaders to hold everyone accountable.

Implement achievable short-term goals. This guarantees consistent improvement and prevents stagnation.

Although these steps don’t invoke mental models, they offer helpful insights into the foundation of a healthy organizational culture. When utilized alongside Weinberg and McCann’s suggestions, they can help you nurture effective teams that are prepared for success.

Winning Employees’ Hearts and Minds

Weinberg and McCann further claim that winning hearts and minds is a key mental model for garnering support. In military contexts, this involves directly appealing to citizens’ emotions and reason to gain their support. For instance, Ukraine employed this model in its war against Russia in 2022, with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy framing the war as one against tyranny and evil, while simultaneously combating disinformation by Russian media.

Similarly, winning hearts and minds in a business context ensures that employees are intrinsically motivated. To do so, clearly communicate values and demonstrate the tangible needs your business meets. In turn, you’ll win employees over to your cause, which encourages them to persevere through challenges. By contrast, employees who are only extrinsically motivated will jump at the opportunity to leave when another offer satisfies their extrinsic desires better—for instance, when a higher-paying job comes along.

Building Organizational Health for Remote Companies

Weinberg and McCann’s advice for winning hearts and minds is geared toward companies that operate in-person. However, the Covid-19 pandemic shifted many companies to remote work. For such companies, it can be harder to establish a cohesive organizational culture, since there’s less in-person interaction to reinforce norms and values. But there are strategies to mitigate this problem:

Organize monthly all-hands’ meetings, which provide an avenue for clear communication and strengthen your team’s sense of belonging.

Introduce fun team-building activities, which reinforce the personal connection between your team members.

Create avenues for casual conversation, which yields a warmer environment.

Praise individual accomplishments, which reminds employees that they’re appreciated.

Manage the Individual

In addition to team-building, maximizing potential requires managing each employee in the manner best suited to them.

One key to managing individual employees is placing them in roles tailored to their skills. For instance, Weinberg and McCann advise that introverts can be better suited to isolated positions, such as strategic roles, whereas extroverts can perform better in communicative environments, like sales roles.

(Shortform note: Studies suggest that, in the workplace, extroverts are both higher-paid and more quickly promoted than their introverted colleagues. Consequently, introverts are incentivized to act more extroverted. However, introverts who act extroverted in the short term can experience fatigue and diminished performance in the long term. Accordingly, it’s important to avoid excessively encouraging introverts to become more extroverted in the workplace.)

Similarly, recognizing the specific needs of your organization can clarify which employees to recruit. For instance, generalists—those who prefer learning about a broad range of topics—can thrive in start-ups, where employees need to perform a wider array of tasks. By contrast, specialists—those who prefer learning in-depth about individual topics—can thrive in larger organizations, which can afford to invest in experts.

(Shortform note: In The Great Mental Models Volume 2, Shane Parrish and Rhiannon Beaubien observe that the generalist vs. specialist distinction is likewise applicable to entire companies. Generalist companies, like Walmart, offer wide ranges of products. By contrast, specialist companies, like Untuckit (which sells casual men’s shirts), focus on more specific niches.)

Guidance Within the Role

Once placed in the optimal role, employees need further guidance and nurturing to maximize their potential.

In particular, Weinberg and McCann argue that managers should encourage deliberate practice from their employees. A notion pioneered by Anders Ericsson in Peak, deliberate practice occurs when we’re placed in situations at the brink of our abilities and receive consistent feedback on our performance. For example, a novice chess player might analyze positions on the edge of their understanding, then review this assessment with an expert coach.

(Shortform note: In Peak, Ericsson clarifies further components of deliberate practice to keep in mind. For example, deliberate practice needs to involve precise, objective measurement; there must be a concrete way to determine your performance and progress. Moreover, deliberate practice must be competitive; you need incentives to succeed and disincentives to fail.)

Gain Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Once you’ve learned how to fulfill your team’s potential, the final step is to derive a sustainable competitive advantage. In essence, this is a long-term edge over competitors that you can exploit. For example, Tesla has derived a sustainable competitive advantage by producing its own car batteries, which consistently cuts costs while delivering higher-quality batteries than the competition.

Though sustainable competitive advantage is widely touted as the holy grail of business, some recommend instead pursuing transient advantages, short-term edges that collectively yield long-term success. In particular, they argue that sustainable competitive advantage is unrealistic, as globalization and increased digitization have made it harder to derive long-term edges. So, rather than pursuing sustainable advantages, they recommend seeking short-term advantages to exploit.

For example, Amazon gained transient advantage by offering incrementally more products: It started as a platform for selling books, then added CDs, then expanded to products like toys and electronics, and eventually launched a streaming service. None of these advantages were sustainable—other companies also sold CDs and goods online, and other streaming services emerged—but each one provided a short-term advantage that Amazon exploited for a certain period. (However, these short-term edges may have collectively yielded a long-term edge, because the sheer range of products available on Amazon is now a sustainable competitive advantage.)

Finding Secrets

Weinberg and McCann suggest that one key to deriving a sustainable competitive advantage is finding secrets. Typically, these are little-known pieces of information that can yield high-leverage opportunities. For instance, in the late ’90s and early 2000s, Canadian sports bettor Bob Voulgaris used data analytics to identify edges when betting, as casinos weren’t yet systematically using analytics. From this secret, he netted millions.

However, secrets can also be well-known information deemed too risky to act upon. For example, the possibility of electric cars was well-known before Tesla; in 1900, they were even the most-purchased car type. Yet, because it was widely assumed that they were financially untenable, traditional automakers decided to focus on gas-powered cars. By challenging this assumption, Tesla exploited a widely known “secret” to become a trillion-dollar company.

While there’s no foolproof method to finding secrets, Weinberg and McCann encourage intellectual curiosity and openness to new ideas from unexpected places. More concretely, they recommend surrounding yourself with people from other fields, since secrets in one field are often well-known in another.

Further Steps for Finding Secrets

Weinberg and McCann cite Peter Thiel’s book, Zero to One, as the origin of their proposal to find secrets. In the book, Thiel offers several additional steps for finding secrets:

Believe that secrets are out there. Resist the temptation to believe that we’ve already uncovered all the relevant secrets.

Examine questions that mainstream thinkers seem to ignore or deem worthless. These questions often reveal secrets.

Be willing to look foolish by questioning conventional assumptions. Adherence to these assumptions can inhibit our ability to unearth secrets

Historically, the Wright Brothers exemplified these steps in developing the first successful airplane. By questioning the conventional assumption that flying was technologically impossible, they discovered secrets—like using wing warping to generate more lift—which culminated in a successful flight in December of 1903.

Reaching Product/Market Fit

Despite their importance, Weinberg and McCann argue that secrets alone can’t guarantee success. Rather, they help us design a product that fills a gap in the market and consequently becomes in demand. In other words, secrets help us develop product/market fit.

Product/market fit is pivotal in determining which of various similar products will thrive. After all, although over 170 companies currently produce smartphones, only one of them is Apple. More generally, the first product that reaches perfect product/market fit is likely to succeed.

(Shortform note: Products that attain product/market fit still undergo the product life cycle, often culminating in market decline, where they fall out of favor with consumers. For this reason, it’s important to continue adapting even after reaching product/market fit, or your success could be short-lived. Once again, it’s key to remember Simon Sinek’s advice in The Infinite Game: treat business as an infinite game, where the goal is to continue playing.)

Customer Development

To achieve product/market fit, Weinberg and McCann advocate engaging in customer development. Simply put, this involves experimenting with your customer base so that you best understand their perspective. By keeping this perspective in mind when creating your product, it’s more likely that your product will be attuned to customers’ wants and needs.

For example, customer development might occur via focus groups, where random samples of customers discuss your product before its launch and share impressions. Harkening back to Part 2, this process lets you de-risk assumptions about your product’s viability and potential. By incorporating the feedback gleaned from customers into further iterations of your product, Weinberg and McCann claim that you’ll be able to quickly reach product/market fit.

(Shortform note: Weinberg and McCann discuss customer development in the context of specific products. However, customer development is also applicable to entire business models. In particular, start-ups can use customer development to determine the strengths and weaknesses of their potential business models. For example, start-ups might run surveys to assess consumer needs, and develop business models to meet those needs.)

Minimize Damage from Conflict

Even with sustainable competitive advantages, successful companies must be wary of conflict with competitors. To that end, Weinberg and McCann offer mental models designed to either avoid conflict altogether or minimize fallout once it begins.

Deterrence

To avoid conflict in the first place, deterrence is a useful strategy. This involves employing a threat to deter the opposition from engaging in conflict. Parents of rebellious children, for example, might deter them from sneaking out by threatening to ground them if caught.

As one particularly useful form of deterrence, Weinberg and McCann recommend the carrot and stick model. This model consists of some form of negative punishment (the stick), alongside some form of positive reinforcement (the carrot). For example, a professor might deter students from skipping class by threatening to reduce their grades while also promising a grade boost for those with perfect attendance. By using this model, you reap the benefits of both punishment and positive reinforcement, which increases the likelihood that conflict will be avoided.

(Shortform note: The efficacy of positive reinforcement versus punishment varies depending on your desired goal. Generally, positive reinforcement is more effective at encouraging action, while punishment is more effective at encouraging inaction. However, some argue that this asymmetry doesn’t hold for children, for whom rewards work consistently better.)

Containment

When deterrence fails, the next step is containment. In short, containment involves taking steps to prevent further escalation and minimizing the damage. For example, if you’re a food distributor who’s realized that customers purchasing a particular food product are falling ill, you might recall that product to stop further damage.

Weinberg and McCann argue that, in the long term, containment can prevent further harm, because conflict left unchecked can start a domino effect of further damage. For example, Blockbuster failed to contain initial conflict with Netflix, with Blockbuster CEO John Antioco spurning a $50 million offer to purchase Netflix. This failure to contain the budding problem created a domino effect, ultimately leading Blockbuster to declare bankruptcy in 2010.

(Shortform note: While containment can prevent domino effects, it can also have adverse consequences. For example, consider the historical paradigm of containment: President Harry Truman’s strategy in the Cold War to prevent the expansion of the Soviet Union. To prevent communism from gaining influence, Truman provided military and economic assistance to countries at risk of Soviet invasion. However, scholars allege that Truman’s containment strategy inadvertently inhibited diplomacy and the possibility of dialogue with the Soviets. Containment, then, isn’t always a risk-free approach.)

Appeasement

If all else fails, Weinberg and McCann recommend appeasement, even if you have to make significant concessions to your opposition. For example, imagine you’re locked in a legal battle with competitors that threatens to harm your company’s reputation. In this case, it might be worthwhile to make a settlement offer to appease them. By doing so, you make a short-term concession, but prevent possible long-term catastrophe.

(Shortform note: The most famous historical example of appeasement was actually a flop: In 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement, licensing the German annexation of Sudetenland to appease Germany and avoid further conflict. This decision famously proved moot: Conflict ensued nonetheless. Though the Munich Agreement is often cited as a cautionary tale against appeasement, this may be a case of hindsight bias—thinking an outcome was easier to predict in hindsight than it actually was.)

Exercise: Make Difficult Decisions

Weinberg and McCann offer multiple decision-making models designed to analyze increasingly complex decisions. In this exercise, practice applying these models to decisions you’ve made in the past as well as decisions you’ll make in the future.

Think back to a time when you made a difficult decision. Why was the decision so difficult? What method(s) did you use to reach the decision?

How could you have used one of Weinberg and McCann’s models (pro-con list, cost-benefit analysis, or decision tree) to inform that decision? Use one of the decision-making models to reevaluate your decision.

Describe one difficult decision that you’re either facing, or will face in the near future. Why do you expect this decision to be difficult?

Apply one of Weinberg and McCann’s decision-making models to this decision. How did the model make the decision easier or harder to make??