1-Page Summary

How often have you or your organization come up with an amazing plan, showed it off, admired it, been sure that it’s the solution to all your problems—only to have it die a slow death over the following months? The 4 Disciplines of Execution authors Chris McChesney, Jim Huling, and Sean Covey say this isn’t uncommon, because strategy (making the perfect plan) is much easier and better-studied than execution (actually carrying out your plan). Execution requires behavioral change, which is one of the hardest things to generate in yourself, your team members, and your organization.

McChesney, Huling, and Covey’s system—or 4 Disciplines—addresses this challenge with a framework for achieving important goals in spite of the deluge of day-to-day activities necessary to keep an organization running. This deluge, which the authors call “the whirlwind,” often occupies 100% of an organization’s time and energy, making it the biggest barrier to execution and behavioral change. While they acknowledge that deluge activities are essential, they say organizations need to dedicate 20% of that time to executing important strategies through the 4 Disciplines of focus, leverage, engagement, and accountability.

Overcome the Deluge With the Eisenhower Matrix

The Eisenhower Matrix, a time management tool developed by former US president Dwight Eisenhower and popularized by Stephen Covey, is a systematic way of prioritizing the deluge of day-to-day activities. The Eisenhower Matrix divides tasks into four categories and gives advice about how to handle each category:

Urgent and important: Do it. If you have a task that’s both pressing and significant, you should get it done as soon as possible. Examples include filing time-sensitive reports and attending (some) meetings.

Important, but not urgent: Schedule it. If there’s something that you need to do, but don’t need to do right now, make a plan for when and how you’ll handle it. Examples include employee reviews, team-building activities, and planning sessions. Your work with the 4 Disciplines will fall into this category.

Urgent, but not important: Delegate it. Eisenhower defined this category as tasks that need to be done, but that don’t require you, personally, to do them—hence his suggestion of delegating those tasks to somebody else. In First Things First, Covey says these are tasks that you trick yourself into wasting time on because you mistake time-sensitive tasks for important tasks. Either way, this category is a dangerous time sink and an excellent place to start if you’re trying to free up some time for more important tasks. Which of the tasks in your company’s day-to-day deluge fall into this category?

Neither urgent nor important: Ignore it. Tasks that aren’t significant or time-sensitive are, almost by definition, things that you can safely ignore. Examples might include going through old emails or scrolling social media.

Besides helping you achieve a specific goal, the 4 Disciplines also create behavioral changes that permanently raise an organization’s overall level of performance. Furthermore, the authors claim that their system works for any kind of team, no matter the team structure or the industry; it even works in personal or family settings.

McChesney, Huling, and Covey are executives and consultants for FranklinCovey, a leadership and consulting firm. The 4 Disciplines of Execution is based on their observations and methods. FranklinCovey also offers services in teaching and implementing the 4 Disciplines.

In this guide, we’ll connect the authors’ ideas with those from other popular self-help and business guides such as Awaken the Giant Within and Smarter Faster Better. We’ll also examine where the authors’ methods may be incomplete or unproven in practical settings. Taken together, this guide will provide the background and tools to effectively tackle the processes within this book.

The Wire Cable of Discipline

The authors chose the word “disciplines” to let us know that implementing these changes will require hard work and consistent effort. In The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari, Robin Sharma says that we can picture discipline as a wire cable—numerous small wires braided together like a rope. Individually, each wire is weak and easily broken; when they’re all together, they create a strong cable.

In the same way, numerous small practices and habits reinforce one another to create the discipline and inner strength to carry out your plans and achieve your goals. The introduction of The 4 Disciplines of Execution says something similar: The authors assert that the 4 Disciplines’ greatest benefits come from how they all work together, leading to much greater gains in productivity than if you tried to apply any one discipline on its own. Much of this book (and therefore this guide) is devoted to practical techniques and principles you can use to start creating your own wire cable of discipline.

Discipline 1: Focus

In Discipline 1, you will choose which goals to make your top priorities—ideally one or two goals, three at the absolute most. The authors call these “Wildly Important Goals (WIGs)” in order to emphasize that they should be your primary focus. The authors add that choosing so few goals may feel counterintuitive, but narrowing your focus is crucial for success because the human mind can only devote its best efforts to one thing at a time.

(Shortform note: Although the authors begin this book by separating strategy and execution, in Section 1 they acknowledge that the lines between the two are blurred—that a good strategy must, by definition, be executable. That’s why the first of their 4 Disciplines is about setting effective goals and devoting the proper amount of energy to them, which is generally considered to be part of strategy, not execution. In other words, in order to execute your strategy, you must first make sure that your strategy is a good one.)

For an organization, senior leaders choose the main goal or goals. Then, each team comes up with its own goals to support the organizational goal.

Consider BHAGs—Big, Hairy, Audacious Goals

If you’re a senior leader choosing a goal for your entire organization, Built to Last authors Jim Collins and Jerry I. Porras suggest choosing something bold, risky, and long-term: what they call “Big, Hairy, Audacious Goals (BHAGs).”

The authors argue that such goals are highly motivating, leading to greater efforts and, therefore, better results than “safe” conservative goals. They say that’s true even though BHAGs can take anywhere from 10 to 30 years to accomplish, and even then they only have a 50% to 70% success rate. The important thing is to believe you can achieve your BHAG and put forth the necessary effort to do so.

Your BHAG should be:

Clear: Make your goal concrete and specific (for example, “sell X units” rather than “be the best”). Couch it in simple language that’s easy to remember and communicate to others.

Compelling: BHAGs are meant to be inspirational and motivating. Therefore, it’s important to pick a goal that you and your employees can get excited about.

Challenging and risky: Pick something that has a chance to fail, even if you do everything right while trying to achieve it. If you’re guaranteed to accomplish your goal, then you’re not thinking big enough.

Appropriate: Your goal should reinforce your company’s image and ideology (or the desired image and ideology). For example, a company known for exclusive, highly expensive luxury goods might want its goal to relate to quality or customer satisfaction; it wouldn’t want to set a sales-based goal that drives it to sell cheaper, lower-quality merchandise.

Note that BHAGs are for organizational goals—they’re not appropriate for small team goals. 4 Disciplines will explain in a later section that team commitments should be short-term and revisited on a weekly basis.

McChesney, Huling, and Covey give four rules for choosing team goals:

- Rule #1: No team may choose more than two goals.

- Rule #2: Team goals must directly support the overall goal.

- Rule #3: Teams get to choose their own goals. Senior leaders can veto goals they don’t feel will support the organization, but they cannot choose the team’s goal.

- Rule #4: All goals must include an end point, expressed as follows: “From (current situation) to (desired situation) by (deadline).”

Having laid out four rules for goals, the authors suggest choosing goals by following these four steps:

1. Brainstorm. Ask yourself what kind of change would have the most impact on your organization or team. Consider things that aren’t working and things that, if they worked even a little better, would have a large impact. Involve peer leaders and your team in the brainstorming.

(Shortform note: Most people are familiar with brainstorming, but the person who invented the process—advertising executive Alex Osborn—included a step that many people overlook: Combine and improve the ideas. In other words, many “brainstorming” sessions consist entirely of people throwing ideas at the wall to see what sticks, but true brainstorming means looking for common ground between those ideas and seeing how they can build upon each other.)

2. Appraise. Consider the list of team goals you brainstormed. Which ones will have the highest impact on the company goal?

(Shortform note: You might reasonably be concerned about picking the wrong goal or goals—what if your appraisal is flawed, or the market situation changes? To combat this fear, bear in mind that Rework authors David Heinemeier Hansson and Jason Fried say that the single most dangerous thing you can do in business is fail to make a decision. A bad decision—such as choosing the wrong goal to pursue—can always be reevaluated and changed; a non-decision leaves you stuck, with no feedback to help you choose a wiser course of action.)

3. Check. Make sure that the goal you’ve picked is reasonable. The authors’ criteria for a reasonable goal are: The goal must support the company’s overall goal, must be measurable, must be driven by the team rather than the leader, and shouldn’t depend more than 20% on another team.

(Shortform note: It will be tempting to set easily achievable goals that you can feel good about accomplishing, but it can be more effective to set ambitious goals, or even impossible ones. In Awaken the Giant Within, Tony Robbins explains that setting big goals inspires you to work harder than setting goals you’re confident about reaching—so long as you work with the mindset that progress toward your goal constitutes success, and falling short of the goal is not failure.)

4. Write. Choose your goal and write it in the format specified in Rule #4: “From (current situation) to (desired situation) by (deadline).”

(Shortform note: Writing down goals isn’t just for recordkeeping, it also makes you more likely to follow through and achieve those goals—20% to 40% more likely, according to one study. This is because when you write something down, you’re more likely to retain it and consider it important than if you just trust yourself to remember your goal.)

Discipline 2: Leverage

Discipline 2 focuses on getting from your current situation to the desired situation you defined in Discipline 1. McChesney, Huling, and Covey call this Discipline “leverage” because it’s about using your effort more effectively. Instead of trying to push a big, heavy goal directly, you channel your energy into related goals that you can actually influence, which in turn moves your company closer to its main goal (like using a lever to move a heavy rock instead of trying to lift it yourself).

The authors say one major problem with implementation is that people generally measure results. Butresults, or lag measures, are fixed—they can’t change once they’re measured, and they don’t give you any information on how to proceed. For example, if your goal is to save up a certain amount of money, your only measurement might be the number in your bank account: If it’s lower than your goal, you don’t learn anything about how to increase it.

That’s why McChesney, Huling, and Covey recommend that you find a way to measure your efforts, or lead measures, rather than just your results. So, if you’re trying to save money, you might measure how many hours you worked in a week and how much money you spent during that week (results). But if you focus on working more and spending less (increasing your efforts), you’ll naturally reach your goal of saving up money—this is much more effective than simply checking your bank account and hoping that it’s higher than before.

The authors explain that whatever lead measures you use must have two essential characteristics: It must be predictive (a change in the effort will yield a change in the results) and it must be influenceable (your team must be able to directly impact the measurement without relying on other teams).

So, how do you choose good effort measurements for a team or a company? The authors suggest using the same four steps that you used for goal setting.

- Brainstorm: Ask yourself what kind of changes would affect your team’s goal or goals. Consider things you’ve never done before, things you could improve, and things you’re doing badly that might hamper you. Look at successful companies’ measures for inspiration. Involve your team in the brainstorming.

- Appraise: Consider the list of effort measures you brainstormed. Which ones will have the most effect on your team’s goals?

- Check: Your effort measure must be predictive, maintainable, measurable, and impactful. It must have an effect on the team goal, be driven by the team rather than the leader, and it must be influenceable—your team needs to have control over it—so it shouldn’t depend more than 20% on another team.

- Write: The effort measure statements don’t have a strict format like a goal statement, but they should still be specific, start with a simple verb, and be concise. They should be clear about expectations—does the lead measure need to be done daily or weekly? How often, how much, and how well? Are they concerned with team or individual performance?

How Athletes Do Their Best

The focus on effort, rather than results, echoes the mindset that many athletes use to consistently play at their best. According to sports psychologist Jim Taylor, focusing on results (like winning or losing the game) is ineffective for a couple of reasons:

Worrying about results (especially bad results) makes you nervous, which can stop you from performing your best.

The results are largely out of your control—they depend on your teammates, your opponents, and to some extent on random chance.

Therefore, Taylor instead suggests having these three goals:

Pre-game: Prepare. Do everything within your power to be as ready for the game as you can possibly be.

In-game: Give your all. Don’t settle for playing “well”—play your absolute best. Go all-out, take chances, and push yourself to the limit.

Post-game: Regret nothing. No matter what the outcome was, know that you did your best. Rather than wasting time and energy regretting what happened in the last competition, start preparing for the next one.

All of these same principles apply to business as well: Focusing too heavily on results can lead you to make short-sighted, reactionary decisions that prevent your company or team from doing its best. It’s better to prepare as best you can for whatever challenge you’re facing, give your all, and then start getting ready for the next challenge.

Discipline 3: Engagement

In Discipline 3, the authors tell you to engage your team by making the 4 Disciplines into a game that they can win. You already did some engagement work in the previous two disciplines by consulting your team members about the team goal and lead measures. When people choose their own goals and feel ownership, they’re more engaged. They’re also more engaged when they enter a competition their team can win—humans have a natural urge to compete and love to win.

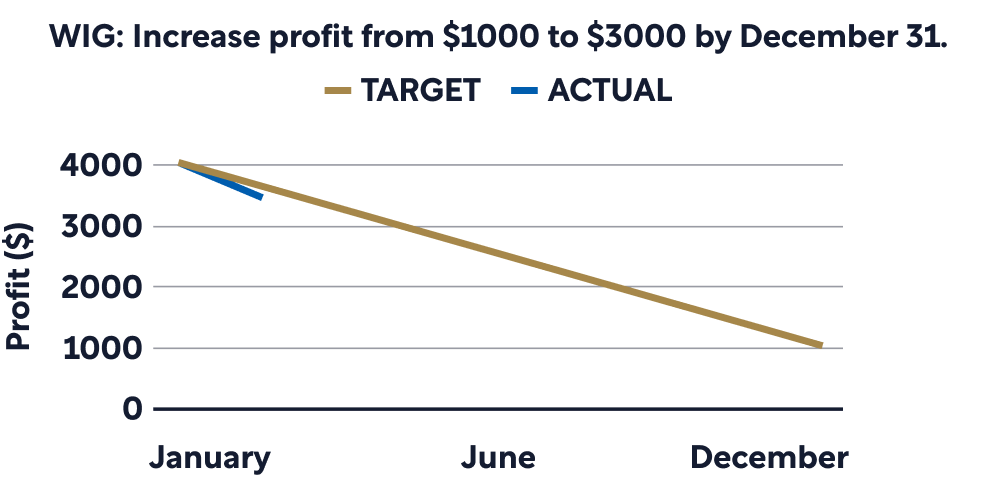

McChesney, Huling, and Covey suggest designing a scoreboard to go with the game; better yet, have your employees design and create it. This scoreboard must tell your team if they’re winning (if they’re on track to meet the goal), and it’s a constant reminder of the game you’re all trying to win. For example, the scoreboard might be a graph with two lines: one that goes from your starting situation to your desired situation over the time allotted (as stated in Discipline 1) and another that shows your actual progress toward that goal.

The authors recommend creating a separate visual for your effort measurement—perhaps a chart where each team member tracks what they’ve accomplished so far that week.

Counterpoint: Gamification Is Unproven

What the authors describe in this section is known as gamification: using gaming elements like scores, leaderboards, and achievement badges to make work more engaging. However, gamification is a relatively new idea, and it’s currently unclear how effective it is.

Gamification started with the observation that gamers will happily spend hours doing repetitive tasks—superficially similar to what they might do at work—with no tangible reward. If managers and executives could make work similarly enjoyable by applying gaming elements, the theory goes, they’d reap benefits in employee morale and productivity—the workers would be happier and the company would be more profitable, creating a win-win situation.

Unfortunately, gamification has had underwhelming results. Common criticisms of the practice include:

It’s a new name for old ideas. Employee competition and leaderboards are hardly new ideas (for example, “Employee of the Month” awards existed long before gamification).

It can feel condescending. Employees work for money; trying to boost engagement with prizes and badges can feel like you’re trying to win them over with cheap gimmicks instead of increased wages.

It misses the point. Gamers play games because they’re fun. Applying gaming mechanics to something that isn’t inherently fun won’t get people engaged, so gamification is doomed to fail.

Discipline 4: Accountability

In Discipline 4, the authors recommend holding a weekly accountability meeting—what they call a WIG (Wildly Important Goal) session. Because achieving the goal is now a game, people are accountable to their teammates as well as the boss. When people know others are depending on them, they’re more motivated and engaged, they try harder, and performance becomes a matter of personal pride. Regular goal sessions and mandatory attendance are key to this discipline—accountability requires consistency.

According to the authors, the goal session should take place at least once a week, last less than 30 minutes, and have a specific agenda: Review the scoreboard, report on last week’s commitments (and celebrate them), and come up with new commitments.

McChesney, Huling, and Covey say that goal session commitments must influence your current effort measurements (deluge tasks—the endless day-to-day business of running the company—do not belong in these meetings). Commitments must be focused, specific, impactful, and take no longer than a week to complete. The person who makes the commitment must be able to do most of the work themselves.

The authors add that leaders should make weekly commitments too. The most effective commitments for leaders are ones that help their team achieve their individual commitments and improve their execution. For example, if a team member requires a new piece of software, a leader could secure approval for the purchase.

Accountability Requires Empowerment

To hold employees accountable for their commitments, you must first empower them to carry out those commitments. The authors say that team members should choose their own goals, and that any individual commitment must be achievable by the person who made that commitment, but they never directly address employee empowerment.

The Leadership Challenge explains how to empower employees, noting that empowerment directly leads to accountability. In brief, it works like this:

Give employees the authority to make decisions and carry them out—remove as many managerial controls and approval processes as possible.

Hold employees responsible for the decisions they make and the actions they undertake, both the good and the bad.

Employees will naturally develop feelings of accountability. Because they’re acting on their own authority and reaping the benefits (or penalties) of their decisions, they’ll develop a sense of ownership for their work: It truly feels like their work, rather than something they’re doing for their boss or for the company.

The Leadership Challenge also notes that empowered, accountable employees will be much more engaged with their work (remember Discipline 3)—because they feel responsible for their own projects, they’ll naturally go beyond their specifically assigned roles and tasks in order to achieve the best results possible.

Implement the Four Disciplines at the Organizational Level

The authors provide six steps to implement the 4 Disciplines across an entire organization:

- Choose the overall goal. Use the steps in Discipline 1.

- Choose team goals and lead measures. Use the steps in Disciplines 1 and 2.

- Train leaders in the 4 Disciplines. The training covers what the disciplines are, how to teach and communicate them to their teams, how to solicit feedback, and roleplay practice. The authors have free resources for doing this on their site, and also offer paid consulting and training services.

- Launch the program. Team leaders hold a two-hour launch meeting with their respective teams, during which they explain what the 4 Disciplines are, communicate and solicit feedback on the goals and lead measures, and explain the scoreboard.

- Guided execution. Someone deeply familiar with the 4 Disciplines helps everyone through the weekly practice of attending goal sessions, making commitments, and keeping score.

- Quarterly meetings. Every few months, leaders attend a leader version of a goal session. Each team leader will discuss their team’s progress, and they can also be recognized for their successes.

Overcome Resistance to Change

One thing McChesney, Huling, and Covey don’t explicitly address in this process is the need to get people on board with the new direction you’re taking. Major changes in company or team processes (such as implementing the 4 Disciplines) often lead to pushback from employees and team members.

Heading off that resistance—and dealing with it if it does arise—can be key to successfully implementing the 4 Disciplines and other major changes. Here’s one method of overcoming opposition to change:

Raise awareness. Get people talking about the change, even if what they have to say about it isn’t good at first. Allow your employees to have intense discussions about it, and welcome criticism and feedback.

Explain why. Once employees know what is happening, tell them why it’s happening; how the new process will benefit them and the company as a whole.

Adjust the process. Take employee feedback seriously, especially from the ones who are most opposed to the change. Addressing their concerns can often make a good change even better, and they’ll feel more engaged with the process if they’re able to contribute to it.

Acknowledge past mistakes. If your company has a history of making bad changes, even if you had nothing to do with those changes, you may have trouble convincing employees or team members that this new process will be for the best. The best way to overcome past failures is to admit to them and, if possible, to correct the past mistakes.

Benefit From Permanent Behavioral Changes

As your team and organization move through the 4 Disciplines process, the behaviors your team members have adopted in each Discipline (like engagement and accountability) will start to become habit.

The authors say there are five stages of behavioral change during this process:

- Set the stage. In this stage, your team gets involved in choosing the team goal and lead measures and settling on a time for the weekly goal session.

- Begin the process. Officially launch the program. The top 20% of your team will get on board right away, 20% will resist, and 60% will be somewhere in the middle. Make sure everyone keeps following the process and, as the leader, demonstrate commitment to the method.

- See good results. Once your team starts to see results, they’ll stop being so resistant to the new changes, become more engaged with the process, and become more accountable for their own contributions to it.

- See even better results. Now the team members are actively changing their behavior, often even more than the lead measurements require. The whole team’s performance improves.

- The 4 Disciplines are second nature. By the time your team achieves its goal, the behaviors they adopted to reach it will be habits. Your team will be well-prepared for the next challenge, and the achieved goal goes back into the daily deluge.

Counterpoint: Don’t Get Complacent

It’s not always enough to go through an organizational change like the 4 Disciplines and trust that the changes will stick. That’s why the business fable Our Iceberg Is Melting has another step after you reach your goal: Don’t get complacent.

Rather than patting yourself on the back and going back to business as usual, Iceberg authors Holger Rathgeber and John Kotter say there are two necessary things to make sure your organization continues to benefit from the work your team did:

Make sure the changes will stick. The authors of 4 Disciplines are confident that people will naturally keep using their method—however, it’s more effective to officially write the process and expectations into your company or team policy. Doing so will ensure that employees (even those who weren’t involved in the process the first time) will know how to effectively set and reach goals and why it’s important to do so.

Be ready to do it again. There will always be changes to adapt to and new goals to strive for, so you must always be ready to go through the 4 Disciplines again. The good news is that it will be easier after the first time, because your employees will (mostly) be familiar with the process and will have seen that it’s effective—therefore, there will be less resistance and less time lost to teaching the process.

Strategy vs. Execution—Or What Vs. How

There are two parts to getting results, strategy and execution. Strategy covers what to do to achieve change (the plan) and execution covers how to actually do it.

Strategy is the easier of the two and traditional business education (such as MBAs) focuses on it. To learn strategy, you study a single organization in depth. You look at “photographs” (single moments in time) of the company or executive. Then you copy what’s working.

Execution is more like a movie. You have to study it over time, and you have to study many different companies. You look at why things happen. Execution, at its most powerful, involves behavioral change, and not just your own. Execution is hard because you have to change the behavior of other people. Sometimes this is the behavior of certain people in the organization, sometimes it’s everyone in the organization. And a grudging agreement to temporarily change won’t work—you need people’s commitment and engagement.

Types of Strategies

There are two main types of strategies, stroke-of-the-pen strategies and behavioral-change strategies:

- Stroke-of-the-pen. These strategies are executed by an order or authorization. They use resources such as planning, money, and so on, and they are almost guaranteed to execute. They sometimes evolve into strategies that require behavioral change

- For example, they are things like a major investment, adding new staff, or changing a product mix.

- Behavioral change. These strategies are executed by getting people to do something different. The resources are people, and these strategies often fail to execute.

- For example, they are things like getting a department to use a new software system, getting two teams to collaborate, or reducing costs.

A study from consulting firm Bain & Company found that about 65% of initiatives required major behavioral changes from front-line staff, and the managers often fail to consider or plan for this. You’re more likely to hear a manager complaining about the specific employees than how hard it is to get people to change their behavior. Specific employees aren’t the reason strategy fails to execute. The system is the reason, and as a leader, the system is your responsibility.

Why Execution Fails

There are many reasons you and your company fail to effectively execute your strategies, including “the whirlwind.”

The Whirlwind

The main reason execution fails is because of the whirlwind—day-to-day operations urgently required to keep the organization running. The whirlwind takes up so much energy and focus that people don’t have energy or time left over to do new things. Urgency (the whirlwind) will beat out importance (new goals) every time. This is why most strategic goals fizzle out rather than blow up.

You’ve probably seen the effects of the whirlwind on your staff. For example, have you ever been explaining a new goal to someone and found them not really listening? While you’re talking, they’re thinking about the day-to-day tasks the conversation is taking them away from, what they might call “their actual work.” A teacher buried under essays to grade and swamped by parent-teacher conferences doesn’t have time to think about long-term goals like improving test scores.

Other Factors

Besides the whirlwind, there are some other more goal-specific reasons execution fails:

- People don’t know or understand the organization’s goal.

- For example, in one of the authors’ initial surveys, they discovered that only 1/7 of employees could successfully name even one of their organization’s top goals. The other 6/7 named a goal that didn’t exist. The lower the person was in the company’s hierarchy, the worse their understanding of the goal.

- Lack of passion.

- For example, in the same study, the authors learned that only 51% of people were passionate about the goal.

- Accountability.

- For example, the study found that only 19% of people were held accountable for their work on the organization’s goals.

- Lack of actionables.

- For example, the study found that 87% of people didn’t know what they were actually supposed to be doing to achieve the goal.

There are more subtle reasons too, such as lack of trust, bad compensation, bad processes, and bad decision making.

4DX—A Path to Execution

4DX stands for the 4 disciplines of execution. 4DX is an operational system containing the disciplines: focus, leverage, engagement, accountability. They are principles (not guidelines or practices) that help you not only achieve a particular strategy, but that create lasting behavioral change, therefore permanently amping up the performance of your team. 4DX has some ancillary benefits as well, mainly that your employees will become more engaged, and they can apply what they’ve learned from 4DX in the workplace to their personal lives.

The four disciplines aren’t new ideas or rocket science—they’re natural laws. Companies such as Weight Watchers have been successfully using similar methods for years. You’re probably already goal-setting, collecting data, creating scoreboards, and holding meetings. However, 4DX takes you beyond understanding principles to actually implementing them. 4DX prescribes a specific, particular way of applying the four disciplines that should earn you the kind of results you’ve never been able to achieve before.

The authors researched the disciplines, experienced trial and error, and have offered the following list of research to assure you that 4DX is well-tested and will work in any country or field:

- Surveyed 13,000 people internationally

- Surveyed 17 different industry groups

- Internal assessments of 500 companies

- Survey almost 300,000 leaders and team members

- Worked with people in 1,500+ implementations

Remember that the disciplines are laws of nature. It doesn’t matter if you like them or even think they’re necessary—they will act on you. You may as well learn to use them.

4DX is not designed for calming the whirlwind—it is designed to help you execute strategic goals while still maintaining the whirlwind.

There are 3 things to keep in mind while reading this book:

- The disciplines are easy to understand but hard to put into practice. They take a lot of effort over a long period of time. The end goal has to be wildly important to merit the commitment. When you achieve the end goal though, you’re not just achieving that specific goal; you’re training your organization to achieve more goals using the same methods.

- The disciplines are counterintuitive. Some of the things you’ll be asked to do will feel unnatural, or run against your instincts or what you’ve always believed about execution.

- The disciplines work in tandem. Using only one might help, but they’re most powerful when used together as they’re interrelated. You must do them in the order they appear.

(Shortform note: The 4 Disciplines of Execution is organized into three parts. Part 1 defines the disciplines, Part 2 describes team implementation, and Part 3 describes organization implementation and some miscellany. For clarity and concision, we have rearranged the information so that the definition of a discipline is followed by the team implementation. We have omitted a section about 4DX software—learn more about it here.)

Defining Discipline 1: Focus

The key of this discipline is to focus on—and only on—the wildly important. Genetically, human beings work best when they do one thing at a time. Multitasking overloads our brains, and when our brains are overtaxed, they slow down. As you practice multitasking, you actually get worse at thinking and problem-solving. As a result, it’s physically impossible to be most effective when concentrating on too much at once.

You can see the harmful effects of multitasking in the workplace too. When you have too many goals, you get hit with the law of diminishing returns. If you have four to ten goals, you might achieve one or two. If you have more than ten, you won’t achieve any of them. Too many or unfocused goals also make the whirlwind worse. What might be five goals at the top of an organization cascades down to many smaller goals at the bottom of the hierarchy, creating too much to focus on. Also, conventional organizational goals often lack measurability, focus, and a deadline.

Therefore, when you want to create change, choose one, at max three, very important goals to work toward. Call them Wildly Important Goals (WIGs) to make it easy for you and staff to remember that they’re top priority. These goals should not come from the whirlwind, and this discipline doesn’t apply to the whirlwind. (The whirlwind is made up of the essential day-to-day activities that keep your organization running. If you ignored parts of it, your organization wouldn’t survive.)

Additionally, this discipline helps you more clearly communicate your strategy to your organization. Choosing a WIG forces you to translate strategy from ideas to a specific outcome. When there are only a few specific outcomes, it’s easy for your staff to differentiate what’s goal and what’s whirlwind.

Focus for Leaders

As a leader, however, you can’t simply focus on one sole thing. You can use different parts of your brain at the same time, just don’t overload them. Think of your brain like an air traffic controller. A controller must be aware of all the planes that are approaching, taxiing, or leaving, but only one of those planes is really important—the one that’s landing at this exact moment. Be aware of all your “planes” (tasks including the whirlwind), but only focus on the landing “plane” (your WIG).

Many leaders understand that focus is important, but still find this discipline hard to put into practice. There are both external and internal forces keeping you from focusing, and often the internal forces are more difficult to overcome. Here are the forces:

- Your own nature. As a leader, you’re ambitious and creative, which drives you to do more. You see beyond what others see, and you’re always finding existing things to improve and new opportunities.

- Quest to appear successful. If you try everything, something might work. And if it doesn’t, by taking on so much, you’ve demonstrated a ton of effort, so you look good. Choosing a single goal raises the stakes—if you fail, you don’t have anything to fall back on.

- Difficulty of saying no. Saying no is counterintuitive for leaders, who are by nature people who are looking for opportunities. A further challenge is that opportunities don’t show up all at once. You can’t compare their strengths and weaknesses and choose the best one. When they show up alone, they all look good.

- For example, Apple’s Steve Jobs was very good at saying no. He made a single phone type, the iPhone, instead of the 40 different models his competitors were making.

- Other people’s goals and agendas (particularly those of people above you). You must meet your responsibilities to others as well as yourself. You don’t have any control over how many goals your boss gives you, but you do have control over which goal you choose for a WIG

- Whirlwind. Remember that WIGs are separate from the whirlwind. If you try to turn everything in the whirlwind into a WIG, you’ll be overwhelmed. WIGs require changes in behavior, and no one can change that much at once. Budget 80% of your time and energy to maintaining or slowly improving the whirlwind. Use 20% for your WIGs.

Four Rules for Organizational Application

4DX can be used in any context, but the authors focus on team and organizational settings. Therefore, in much of the following, the authors refer to two types of WIGs: overall WIGs and team WIGs.

The overall WIG is the WIG for the entire organization, chosen by the senior leaders.

Team WIGs are the goals of specific teams. They move the organization closer to the overall WIG, but the focus or language of the team WIGs may be different from those of the overall WIG.

Once an organization has an overall WIG, there are four rules for applying Discipline 1 across the organization:

Rule #1: No team focuses on more than two WIGs.

Across an organization, there may be many WIGs, but within a team, there cannot be more than two.

Rule #2: The WIGs at lower levels of the organization must directly help achieve those at higher levels.

Imagine the WIG at the top of the organization as a war. WIGs at lower levels are battles. The only reason to fight a battle is to help win a war. Once you have an overall WIG, consider how to achieve it with the fewest number of team WIGs (rather than making a to-do list of all the things that must be done to achieve it). This simplifies the strategy.

For example, an Internet provider had a WIG of “Increase sales from $6 to $9 million by February 28.” An outside sales team committed to raising $1 million and the major-account division committed the remaining $2 million. The technology team committed no money but improved the company’s record for uninterrupted service, which was very important to customers and helped the other teams achieve their WIGs.

Rule #3: Senior leaders can veto but not choose the lower level WIGs.

This rule combines the best of top-down (clarity from senior leaders) and bottom up (engagement). The senior leader knows what’s most important, but the team members are the people who will actually have to transform their behavior, so their input is important. If you just do top-down, you’ll have problems with engagement, and accountability might only come from authority. If you just do bottom up, the WIG might not be aligned with the overall WIG. That’s why seniors keep veto powers, in case the team-selected WIGs aren’t appropriate.

Rule #4: All WIGs must contain a measurable result and deadline, in the form of “from point A to point B by deadline.”

This format sounds simple, but many leaders struggle with it. Once they figure it out, they’ve achieved clarity and focus.

Consider a goal in the incorrect format like this one from a travel agent: “Increase customer satisfaction.” How do you measure satisfaction? What is the deadline? In short, how do you know if you’ve achieved it? Put into WIG format, the goal becomes: “Increase our customer satisfaction ratings from an average of 50% satisfaction to 70% satisfaction in six months.”

What should the deadline be? A year is a good starting point (since companies often measure things on a calendar or fiscal year). Some take six months to two years. Any project-based WIGs take around the same time as the project. The time frame must be long enough to achieve a compelling goal, but short enough to maintain enthusiasm for the vision.

Example: NASA

Here’s an example of the effectiveness of adhering to Discipline 1:

In 1958, NASA had seven very important goals along the lines of increasing human knowledge about space, improving spaceships, long-range studies, positioning the US in the space race, military applications, and cooperation with other nations. Some of these goals were measurable, but none of them had a deadline.

In 1961, J.F. Kennedy gave NASA a WIG in the correct “from point A to point B by deadline” format: put a man on the moon and bring him back before 1970.

There were three lower-level “battle” WIGs to support Kennedy’s “war” WIG:

- Get a spacecraft to the right position on the moon, keeping in mind that the moon is moving in orbit.

- Find a way to power rockets carrying heavy lunar modules fast enough to break free of Earth’s gravity.

- Develop a capsule and landing gear that would keep a person alive both in transit to and from, and while on, the moon.

When Kennedy announced his WIG, accountability, morale, and engagement at NASA exponentially increased. At the time, NASA didn’t have the technology to achieve any of the three “battle” WIGs, but they got it done—Neil Armstrong walked on the moon in 1969.

(Kennedy was also a good example of saying no to good ideas. He was asked why he chose to focus on man-on-the-moon instead of other worthy goals, and he said this goal was most important.)

A Note on Project WIGs

Discipline 1 still applies to project WIGs, but you need to be careful about your point B value. The obvious choice is 100% completion, but that’s not as concrete as a numerical value such as profit or revenue. Once you factor in things like scope expansion, it might be hard to actually measure project completion. Instead, relate the point B value to the business outcome. Add to your from point A to point B by deadline.” For example, “Launch a new app by July 31, meeting 100% of the specified e-commerce functions.”

Exercise: Why Is Focus So Hard?

Most leaders know that focus is important but find it difficult to do.

What factors make it difficult for you to choose a focus? Consider internal factors such as your own nature or desire to look good, what others ask of you, and your whirlwind.

Think of three new projects you’re excited to work on. Then, choose only one of them. How did you decide which one to pick?

Implementing Discipline 1: Focus

A WIG must challenge your team, but it must also be achievable. Don’t game your team by choosing something impossible while privately thinking if they manage 75% of it, you’ll be happy. Long-term, this will affect your ability to engage your team and produce results.

There are four steps to selecting WIGs:

Step 1: Brainstorm a List of Possible WIGs

To brainstorm, come up with ideas on your own and consult team members and peer leaders, if applicable.

Brainstorm on Your Own

Brainstorm a list of possible WIGs even if you think you already know what the WIG should be. Ask yourself, “If everything about my organization stayed the same, where would a change have the most impact?” (Don’t ask, “What’s most important?”—you’ll get distracted by the whirlwind and other people’s opinions.) Come up with as many ideas as you can. The more ideas you have to choose from, the better your final WIG will be.

To come up with ideas, look within and outside of the whirlwind, and consider your mission.

- If you’re choosing a WIG from inside the whirlwind, your options are:

- Something that’s very badly broken that absolutely must be fixed, for example, going over budget

- Something in your value proposition that isn’t working, for example, unsatisfactory customer service

- Something that’s already going well but would have a large effect even if it was only improved a little, for example, an increase from 80% to 90% satisfaction could generate a lot more revenue

- If you’re choosing from outside the whirlwind, your WIGs will usually be about strategy. (This kind of WIG will be totally new to your team and will require an even bigger change in behavior.)

- For example, you might want to launch a new product

- If you’re choosing something to align with your mission, consider results beyond your organization

- For example, a thrift-store chain got a new president. The old president had done a good job and the company was doing well financially and operationally, so the company looked at choosing a WIG to do with their mission, which was to help people with disabilities and people who are homeless become more self-reliant. They eventually decided that the WIG should be to help workers with disabilities find jobs outside their organization. The thrift-store company couldn’t hire every person with a disability, but they did have the capacity to train them in retail.

Brainstorm with Team Members

Including team members in the discussion of choosing a WIG increases their engagement with that WIG. They have different skill sets and knowledge bases than you, so they might come up with ideas you never could have. They’ll also be the people doing a lot of the work in the next three disciplines, so it’s important they be consulted.

In addition to the same things you would consider yourself, consult your teammates on the following:

- To achieve the overall WIG, what area of team performance do you want to improve? (Assuming that all current performance stays the same)

- In areas where the team is already succeeding, what one strength would you improve even more to contribute to the overall WIG?

- In areas where the team is struggling, what one weakness most needs to be improved?

(If your team is really big, you can talk to a representative group.)

Brainstorm with Peer Leaders

Peer leaders are particularly important to consult when your organization has an overall WIG. These leaders may depend on you, or you on them. While brainstorming with peer leaders, in addition to the same things you’d consider alone, ask for ideas regarding:

- If your team is part of an organization with many goals, figure out which goals are most important.

- If your organization already has an overall WIG, come up with ideas that will directly contribute to it.

- If the team is the whole organization, come up with ideas that will grow the organization or support the mission.

If your team is a support function (HR, finance, IT, and so on), wait to choose your team WIG until after the line functions finalize theirs. Then, you can use your WIG to help them achieve theirs. For example, if a sales team wants to move to a new model, HR can choose a WIG that involves helping people get the training they need.

Shortform Example: Book Production Department: Brainstorming

Each implementation section, throughout the whole summary, will reference the experience of the production department of a publishing house.

Maria is the leader of the production department of a large publishing house. When the publishing house started implementing 4DX, the senior leaders came up with this overall WIG: “Decrease costs from $1 million to $800,000 by the end of the year.”

The production department (and all the other departments of the publishing house) brainstormed team WIGs that would support the overall WIG. Maria and her team came up with a list of ideas such as:

- Reduce the need for outside help such as freelance designers and photographers

- Reduce the number of at-press changes (once the printer has set up files, there’s a charge per changed page)

- When purchasing stock images, avoid the more expensive rights-managed agencies

Step 2: Assess Impact

Once you have a list of possible WIGs, determine the ones that have the most impact on the overall WIG.

Some guidelines:

- If the overall WIG is financial, then the team WIG should have something to do with money: revenue, profitability, cost savings, etc.

- If the overall WIG is quality, then the team WIG could have something to do with productivity or customer satisfaction.

- If the overall WIG is strategic, then the team WIG could address the mission, new opportunities, or how to reduce threats.

Shortform Example: Book Production Department: Assessment

Maria and her team calculated the possible savings of all their ideas. Maria now knew which WIG would reduce costs most in her department, but she was looking for a WIG that would have the greatest contribution to the entire publishing house. At-press changes were not only expensive, they also caused a delay. When books printed a week later than scheduled, the marketing department had to pay for rush rather than regular shipping to ensure books made it to events on time. Marketing would also benefit from the stock image idea. Every time a rights-managed image is used, there’s a fee. If book covers used royalty-free images instead, marketing could then reuse the image in press kits and promotion materials without any additional cost.

Step 3: Test the Top Team WIG Candidates

Test each potential WIG. If the answers to all of the following questions are yes, the WIG passes the test.

- Does it support the overall WIG? Review step 2.

- Is there a way to measure it? There must be a way to measure it from the very first day. If you have to build a measurement system, choose a different WIG, because there’s no point starting 4DX without a score.

- Can your team achieve the WIG without significant help from another team? Your team should have at least 80% ownership. If it doesn’t, your team won’t feel engaged and accountable. However, it’s fine for two teams to have the same WIG, though, as long as they’re aware they share the outcome (both succeed or both fail)

- Are the results driven by the team rather than the leader? The team needs to have an impact on the results or they won’t be engaged.

Shortform Example: Book Production Department: Testing

Maria and her team tested all their ideas and chose to reduce at-press changes. This supported the overall goal, was easy to measure, didn’t depend on other teams, and the results were team-driven.

Step 4: Write the WIG in the “From Point A to Point B by Deadline” Format

Start with a simple verb.

- Good: Cut costs...

- Bad: In order to create a reduction in costs, we anticipate...

The lag measure must be expressed as “from point A to point B by deadline.”

- Good: from 85% to 95% customer satisfaction by February 28

- Bad: Increase customer satisfaction

Be concrete, precise, and simple.

- Good: Reduce time lost incidents from 8 per year to 1 per year by March 31.

- Bad: Our aim is to increase safety, according to our mission, which is...

Don’t put in any language about how you’re going to do it.

- Good: Increase profit from $8 million to $10 million over six months.

- Bad: Increase profit from $8 million to $10 million over six months by increasing revenue in the following five areas…

Shortform Example: Book Production Department: Statement

Maria and her team came up with this WIG: “Decrease costs for at-press changes from $4000 to $1000 by the end of the year.”

Yield

After implementing Discipline 1, you’ll have a WIG statement in the form of “[Simple verb] from [point A] to [point B] by [deadline].” If you’re applying the discipline across an organization, all of your teams will have their own WIG statement in this format, and the team WIGs will directly support the overall WIG.

Exercise: Choose a Team WIG

There are four steps to creating a team WIG.

Invent an overall WIG for your organization. (If you’re not clear on the overall goals of your organization (not uncommon), or you’re not having a brainwave, you can use this one, which should apply to most organizations: increase profit from point A to point B over the next year.)

Brainstorm a list of possible WIGs for your team. Think of your own ideas first, and then imagine what your coworkers and peer leaders might suggest.

Assess the impact of your brainstormed team WIGs on the overall WIG. Your team WIG should directly contribute to the overall WIG. Consider if the overall WIG is financial, strategic, or quality-related.

Test your best three team WIGs, keeping in mind their impact on the overall WIG. Are the team WIGs measurable? How would you measure them? Would your team depend on another team to achieve them? Is it the leader or the team members driving the results? How do you know?

Write your final WIG in the format [Simple verb] from [point A] to [point B] by [deadline].

Defining Discipline 2: Leverage

Think of your WIG’s point A as a big heavy rock. No matter how hard your team pushes against it, it’s immovable. However, if your team applies a lever, the rock shifts. The team has to move the lever a lot to move the rock a little, but the rock does move. Discipline 2 is about finding the right lever to move the WIG value from point A to point B.

Point A and point B values are also called lag measures. Lag measures are results. They tell you if you’ve reached your WIG, so they’re very important. However, as the name implies, the actions that produced these results have already happened, so there’s nothing you can do to change them. Some examples of lag measures are revenue, profit, customer satisfaction, and body weight on a scale. (The whirlwind of daily tasks is full of lag measures.)

The lever in the rock example above is a lead measure. Lead measures quantify the actions that have the most impact on the WIG. Lead measures don’t tell you if you’ve achieved the WIG; instead they forecast if you will achieve the WIG. They’re predictive of the lag measure and, because the actions that drive them are ongoing, they’re influenceable. For example, if your lag measure is your body weight on a scale, as above, your lead measures are what and how much you eat, and how often you exercise.

Because lead measures directly affect lag measures, the more you move your lead measure, the more your lag measures will move.

Most people know that the lead measures are important. The key to discipline 2 is measuring lead measures. For example, if you’re trying to lose weight, everyone knows diet and exercise are factors. However, not everyone actually measures and tracks calorie intake or time spent exercising.

There are two critical characteristics of lead measures:

- Predictive. A change in the lead measure must create a change in the lag measure.

- For example, consider a lag measure that’s how often your car breaks down. A predictive lead measure would be how often you have it serviced. A non-predictive lead measure would be what color you paint it.

- Influenceable. Specifically, directly influenceable; your team must be able to influence this measure without dependence on another team or outside force.

- For example, consider the lag measure that’s how many crops you grow. An influenceable lead measure would be how often the crops are fertilized. A non-influenceable measure would be the amount of rainfall—there’s nothing anyone can do about it.

Why Leaders Fail to Focus on Lead Measures

Though fixating on lag measures doesn’t get results (because the lag measures are the results), leaders focus on them for two reasons:

- It’s easier to get data on lag measures than lead ones. There are almost always already systems in place to measure lag measures; sometimes you have to come up with a new system to get lead. It takes discipline to keep getting data.

- For example, it’s easy to step on a scale and weigh yourself (lag measure), but it’s a lot more work to keep track of how many calories you eat or how many minutes you spend exercising (both lead measures)

- Lag measures are the results you have to achieve and the results you’re held accountable for. It’s not surprising that people focus on the numbers that measure success and failure.

Even when leaders shift their focus away from lag measures, they may still struggle with lead measures. Why? It’s rarely a matter of ignorance or effort—most leaders have some idea of what factors will influence their results. Leaders struggle with lead measures because:

- They aren’t employing Discipline 1. Even if they know what the lead measures are, they’re not focusing on them because they’re dealing with too many goals, or they’re stuck in the whirlwind.

- They know what the lead measures are but they don’t know if anyone’s actually doing them because they’re not tracking.

- For example, suggestive selling is hardly a new idea in retail, but salespeople have to actually do it, regularly, for it to work.

Implementing lead measures is the hardest part of 4DX because:

- They’re counterintuitive. Lag measures are the obvious place to focus, because the results are what matter.

- They’re hard to measure. Tracking behaviors (especially new ones that have never been done before) is harder than tracking results. On the bright side, it’s so much work to get data on lead measures that if you were tempted to disobey Discipline 1, you’ll self-enforce once you realize the time commitment required for measuring even a single WIG’s lead measures.

- They come with a false sense of simplicity. They require focus on a single behavior that might not seem relevant, especially to those outside the team.

Types of Lead Measures

There are two types of lead measures, both perfectly acceptable to use in Discipline 2.

- Small outcomes are lead measures that create multiple new behaviors. The team must achieve a result, but everyone can use whatever method they want, and the team is accountable for the result.

- For example, achieve average customer satisfaction scores of 80% each week.

- Leveraged behaviors are lead measures that force everyone on the team to do the same beneficial behavior. The team doesn’t have to achieve a result, but must do specific behaviors throughout the week, and the team is accountable for doing the behavior.

- For example, each team member must help at least 50 customers per week.

Example: Water-Bottling Plant

Here’s an example of one company’s journey to find influenceable, predictive lead measures:

A water-bottling plant came up with the following WIG: “Increase bottling from 45 million gallons to 50 million gallons by the end of the year.”

At first, the company struggled to understand the difference between lead and lag measures. Their early suggestions for lead measures were to keep track of water production by day or month—these might be more frequently measured than the WIG result, but they’re still lag measures. Then, the production manager identified a problem that stopped the company from producing more water—the machines had too much downtime.

The next step was to translate the problem into a lead measure. They came up with: complete preventative maintenance on each machine once a week.

Water production increased at a rate faster than anyone expected. The plant had known that the factor they chose as a lead measure was important, but instead of focusing on only this factor, they’d been trying to tame the whole whirlwind at once. Their efforts were so spread out they had little effect on anything.

A Note on Process-Oriented Lead Measures

If your WIG comes out of a process (for example, a ten-step sales process), you might find your lead measure within the process itself. Look at the individual steps of the process. Where are the leverage points? Where is performance failing? Make those leverage points your lead measures. For example, if step 4/11 is business analysis, and this is a place that would have the most impact on the process result, look for a lead measure there.

If you try to improve the whole process at once, you’re forgetting Discipline 1.

A Note on Project WIGs

Project milestones aren’t necessarily good lead measures. They have to be predictable and influenceable like any lead measure, and they also need to take long enough and be significant enough that a team can make weekly commitments to them.

If your WIG is multiple projects, it’s more useful to choose lead measures that apply to all projects, such as procedures like project communication.

Implementing Discipline 2: Leverage

Finding lead measures can be challenging. If you’re trying to do something you’ve never tried before, you have to do new things. How do you know what these new things should be? Like coming up with a WIG, there’s a four-step process:

Step 1: Brainstorm a List of Possible Lead Measures

Like step 1 of WIG brainstorming, come up with as many ideas as possible. The most effective lead measures may not be the ones that first occur to you. Make sure you focus on ideas that will help achieve the WIG. You’re not looking for a catch-all list of things it would be good to do. Coming up with lead measures requires a bit of that Discipline 1 focus.

While brainstorming, consider:

- What have we never done before that will help achieve the WIG?

- What are we good at that we can use to achieve the WIG?

- What are we bad at that might get in the way of us achieving the WIG?

- What are the activities we already do that are most important to achieve the WIG? Keep in mind the 80/20 rule—80% of your results will come from the top 20% of your actions. Choose your lead measures from these top activities.

- What did other people or companies with similar WIGs do? What were their lead measures?

Shortform Example: Book Production Department: Brainstorming

Maria and her team brainstormed many possible lead measures, including:

- Create a pre-press checklist to catch the most common errors

- Find printers that don’t charge for at-press changes

- Ask the author to do a final review of the book files

- Run preflight software on book files before sending to press

- Ask another staff member to look over files before submission

- Create a consistent file-naming convention so no one accidentally submits the wrong file

Step 2: Assess Impact

Determine which lead measures will have the most impact on the team WIG. Probably all the ideas you come up with are good ideas, and you and team members feel like you should be doing all of them, but don’t fall into this trap—pick just a couple.

Shortform Example: Book Production Department: Assessment

Maria and her team narrowed their ideas down to these top three:

- Create a pres-press checklist. Many of the at-press changes were the same mistakes in different books.

- Run preflight software. Software would catch errors not easily visible to the eye.

- Create a consistent file-naming convention. When book files didn’t have version numbers, it was difficult to tell which file was the final version.

Step 3: Test the Top Lead Measure Candidates

Test each potential lead measure. If the answers to all of the following questions are yes, the lead measure passes the test. Four of the questions are the same as in the WIG test, noted with an asterisk (*).

- Is it predictive? Will the lead measure influence the lag measure?

- *Can your team achieve the WIG without significant help from another team? (Is it influenceable?)

- Is it maintainable? The goal of a lead measure is to make new behaviors a habit. Therefore, ongoing processes are a better choice than one-offs.

- Ongoing processes: Attend all meetings of the volunteer executive.

- One-off: Sign up to be a member of a volunteer executive.

- *Are the results driven by the team rather than the leader? The team needs to engage with the measure or they won’t be interested.

- Weak lead measure: A leader more frequently audits.

- Strong lead measure: A team responds to audit findings.

- *Is there a way to measure it? You have to be able to measure the lead measures.

- Is the lead measure worthy of the effort it will take to carry out and measure? The lead measure must create enough impact to be worth the trouble, and shouldn’t have any negative side effects

- For example, a fast-food chain hired inspectors to visit restaurants. All the workers thought the inspectors were spies and morale dropped.

Shortform Example: Book Production Department: Testing

The production department’s lead measures passed all the tests.They were predictive, influenceable, maintainable, team-driven, measurable, and didn’t create any negative side effects. While testing, the department realized that it would be easier to remember to run preflight software if it was part of the checklist, so they combined those two measures.

Step 4: Write the Lead Measures in their Final Form

When writing your lead measures in their final form, consider the following, and be specific. The considerations that are the same as for the WIG are noted with an asterisk (*).

Individual vs. team?

- If you track individual performance, you create a high level of accountability, but it’s harder to get perfect results because everyone has to meet the same standard. This requires detailed scorekeeping.

- For example, each person must sign up two people for the customer loyalty program per day

- If you track team performance, you allow differences in performance between team members, but it’s easier to achieve results because team members can make up for each other’s weaknesses (not necessarily a good thing—low performers can hide).

- For example, the whole team must collectively sign up ten people for the customer loyalty program per day

Daily or weekly? (Weekly is the minimum.)

- If you track daily, you create the highest level of accountability because each day must be the same

- For example, sign up two customers per day per team member

- If you track weekly, this allows for variability between days but you’ll still get the same numbers at the end of the week as you would have by tracking daily.

- For example, sign up 14 people per week per team member

How much and how often? Come up with numerical values for your lead measures. Pick numbers that are challenging but not impossible. When making this decision, keep the following in mind:

- Choose higher numbers if it’s a matter of safety. For example, Erasmus swabs 100% of every patient admitted to the hospital because the only acceptable number of hospital-acquired infections for them is zero.

- Use trial and error to land on appropriate numbers. For example, a building-materials client sent out two emails every week before a sale but didn’t get much response. They tried sending out three emails, and it was the magic number.

- Remember that more isn’t always better. For example, for a long time, drug companies very regularly visited docs. Doctors got so tired of them they banished salespeople from their offices.

How well? This is optional, but the best lead measures go beyond numerical values and have a quality component.

- If your lead measure is something your team already does, they have to do it much better than they currently are in order for it to move the lag measure

- For example, a sales team might have a lead measure of: “Upsell the all-inclusive package to four vacationers per week per team member.” The lead measure could additionally include direction about how well each team member must pitch: “Using our proven script, upsell the all-inclusive package to four vacationers per week per team member.”

*Start with a simple verb

- Good: Call five clients...

- Bad: Communicate via telephone...

*Be concrete, precise, and simple

- Good: Sell five pairs of shoes per team member per day.

- Bad: With the goal of increasing profit, sell... (Avoid any how-to language—your WIG already covers why you’re doing things.)

Shortform Example: Book Production Department: Statement

The production department settled on the following lead measures:

- Each team member renames files for two books per week

- Complete the pre-press checklist for 90% of files sent to press

Yield

After implementing Discipline 2, you’ll come out with a short list of lead measures that will drive the WIG’s lag measure.

Exercise: Find Lead Measures

There are four steps to finding lead measures.

Recall the team WIG you came up with in the previous exercise. Brainstorm a list of possible lead measures that will affect the WIG’s lag measures (X and Y). Remember, lead measures must be both predictable and influenceable.

Think about how the lead measures you came up with above will influence your team WIG. You probably came up with several good ideas—narrow the list down to the most impactful two or three.

Test your top lead measure ideas. Are they maintainable, measurable, impactful? What makes them so? Do team members move the measures, instead of the leader? How do you know?

Write your lead measure in its final form. Start with a simple verb and keep the wording concise and concrete. Consider: are your tracking individual or team performance? Is the timeline daily or weekly? How much and how well should the measure be executed?

Defining Discipline 3: Engagement

Discipline 3 engages your team by making the achievement of the WIG into a game they can win. Humans have a natural urge to compete, and people behave differently when they see an opportunity to win—they become highly motivated and engaged, and this drives a high level of performance.

The opposite is also true—it’s human nature not to try as hard as you can if no one’s keeping score. For example, consider this anecdote about an important high school football game. Hurricane Katrina had knocked down the scoreboard, but the field was fine, so the game went ahead. But because the fans couldn’t see the score, no one knew what was going on in the game, and no one cared about the game.

The authors claim that an opportunity to win is one of the most powerful ways to engage people, more powerful than money, benefits, conditions, and workplace relationships. People desperately want the opportunity to achieve.

People perform best when they are personally winning. They don’t necessarily care whether the organization or their boss is winning, they care if the team they’re on is winning.

Winning, in the context of Discipline 3, is achieving the WIG. The score is lead and lag measures.

Your team must always know the score or else they don’t know what to do to win. If they don’t know, they’re not trying to win, they’re just trying to not lose (survive the whirlwind of their daily activities). A conceptual understanding of lead and lag measures is completely different from a team that knows their score.

The leader must set up the game so it’s winnable—the lead measures must influence the lag measures.

Scoring

The score is measured on a literal scoreboard. There are two types of scoreboards, and as you’ll see, the one you want to use is a player’s scoreboard:

Leader’s (“coach”) scoreboard

A leader’s scoreboard is made up of complex spreadsheets or visuals that display leader-level data with an overwhelming amount of data. This scoreboard is so complicated that only the leader can read it or draw any conclusions from it. Leaders create this kind of scoreboard instinctively and you probably already have some version of this that contains data such as historical trends, detailed analysis, and so on.

The leader updates these kinds of scoreboards.

Employees’ (“players”) scoreboard

An employees’ scoreboard is made up of simple, visual graphs that show only the important information—where you are and where do you need to be, i.e., are you winning or losing? Leaders have to consciously choose to create (or ideally get their employees to create) this kind of scoreboard

The players update the scoreboard and it forces them to act.

A player’s scoreboard has these requirements:

- It’s simple. The card should only contain minimal information. Don’t include any extra information such as reports, year-over-year comparisons, and so on. A simple scoreboard is easier to update, and the easier it is to keep score, the less likely it is that people will put it off when the whirlwind strikes.

- For example, consider a scoreboard at any professional sports game. It contains only a few pieces of information such as the score and time left in the game.

- It’s visible. The scoreboard has to compete with the whirlwind for attention, so it needs to require no extra work to access. Put it where people will see it often, or if you have remote team members, do a digital version. A public scoreboard makes people more accountable, because everyone can see who’s contributing most. If you want to be most motivating, post it where other teams can see it.

- For example, if employees on day and night shifts can see each shift’s scores, they might compete to beat each others’ production numbers.

- It’s complete. Typically, scoreboards have a visual for the WIG and each lead measure. The scoreboard must display the target and where the team is currently at. On the WIG’s visual, the target is the point B value. On the lead measures’ visuals, the target is usually a static standard of performance that must be reached and maintained. If you don’t have data on your target, estimate. (For example, if your WIG is to improve something you’ve never measured before, or it's something qualitative.) It is critical to have a target line, even if it’s not based on hard data, because if you don’t have a target, you can’t tell if you’re winning. In the interest of completeness, you can also include:

- Legends and simple labels so everyone understands what the scoreboard shows.

- If your scoreboard is anything other than a trend line, it can be helpful to do the math and show the numerical difference between the target and current numbers.

- You can also do ramp-up targets for lead measures rather than a static target, if you prefer.

- It’s quickly readable. Anyone looking at the scoreboard should be able to tell within five seconds if they’re winning or losing. The scorecard must show where they are and where they should be at an exact moment in time. You can use colors such as red and green to make things even more obvious.

The scoreboard must be regularly updated or people will lose interest and the whirlwind will overtake the game.

The scoreboard itself isn’t what engages people, the game does. For example, no one’s going to comment on how beautiful the scoreboard was at the Olympic gold medal hockey game, they’re going to comment on the game. The scoreboard is a just a reminder—a constant reminder—of the ongoing game.

Example: Production Plant

Here’s an example of the effects of a scoreboard:

A Canadian plant hadn’t hit its target production number in 25 years. The plant was old and remote, their technology was outdated, and they had quality issues (low 70s compared to high 80s in the other companies’ plants). When the leaders put up a scoreboard, everything changed. People realized they were losing, and wanted to turn that around. The night shifts and day shifts competed to be more productive. Everyone knew each other and on the weekends, when they’d hang out and play hockey, they wanted to be able to brag about their shift doing better than the other. The plant’s quality score became the best in the company and the plant massively exceeded its production targets.

Exercise: What Engages You?

People are most engaged when they feel like they’re playing a game they can win.

Imagine the last time you did something without keeping track of the score. For example, you might have been playing catch with your daughter, reading a book, or making dinner. How motivated and engaged were you?

Now, imagine you were doing a version of that activity that involved competition. The examples from above transform into playing a baseball game, coming up with the most insightful response in your book club, and competing in Iron Chef. How motivated and engaged are you now?

Pick an activity you'd like to get better at. How can you use competition to increase your engagement?

Implementing Discipline 3: Engagement

There are three steps to implementing Discipline 3:

Step 1: Choose a Scoreboard Format

There are several options for format:

- Trend line. Trend lines are most effective for lag measures. You can see where you’re supposed to be and where you are.

- Common gauges (speedometer, thermometer, and so on). This is most effective for time measures (for example, process speed).

- Bar chart. This is most effective for comparing performance of individuals or teams.

- Andon chart. An andon chart shows symbols that represent the status of measures, such as a smiley face when something is on target, or a sad face when it's not. This type of chart is most useful for displaying lead measures.