1-Page Summary

The Big Short by Michael Lewis explores the origins of and fallout from the 2007-2008 financial crisis through the eyes of a handful of eccentric and oddball investors who saw that the U.S. housing market—and, by extension, the entire financial system—was built on a foundation of sand.

These investors were lifelong iconoclasts who refused to worship at the altar of high finance. They saw, simply by reading financial statements and exercising basic due diligence in their investment decisions, that Wall Street was caught up in a cycle of irrational exuberance regarding mortgage-backed securities. Major financial institutions had deeply overvalued these securities and had passed them off to investors throughout the financial system.

The group—Steve Eisman, Michael Burry, Greg Lippmann, Charlie Ledley, Jamie Mai, and Ben Hockett—discovered that subprime mortgage-backed collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) were essentially worthless. By simply doing the research and analysis that no one else was willing to do, this group (working largely independently from one another) saw that the CDOs were nothing more than repackaged bundles of mortgages issued to un-creditworthy Americans. These instruments had been wildly overrated by the credit ratings agencies, whose job it was to evaluate the riskiness of the securities. The bonds and CDOs sold for far more than they were worth because they’d been wrongly issued sterling grades from the agencies. The contrarian investors hypothesized that once the interest rates on those mortgages rose or housing prices stopped rising, the bonds and CDOs of which they were composed would become financial toxic waste that would poison the entire financial system.

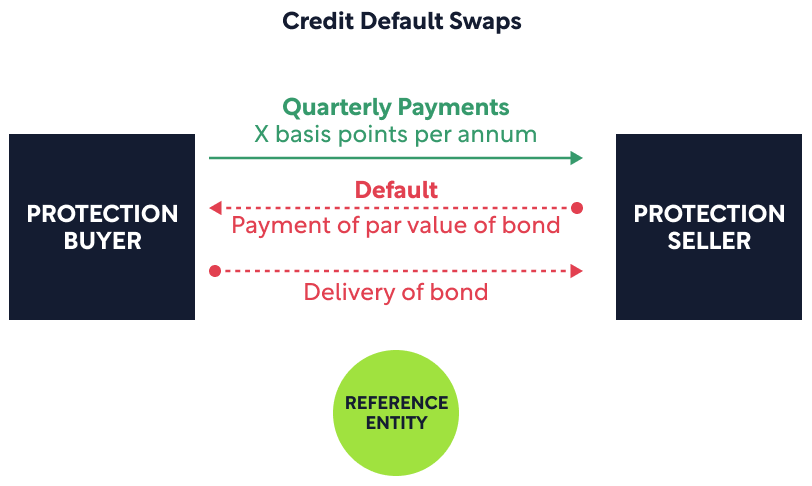

The eccentric group of investors further saw that they could profit from the colossal short-sightedness and mismanagement of major Wall Street investment banks. By purchasing a financial instrument known as a credit default swap, they could bet against (or “short,” in Wall Street parlance) these soon-to-be-valueless bonds and CDOs. The swaps functioned like an insurance policy. The purchaser of the insurance policy paid regular premiums to the seller. In the event of a calamity, however, like the collapse of the housing market, the seller of the swaps would have to pay the full face value of the referenced bond.

The group saw that the impending collapse of the subprime housing market would soon make their credit default swaps worth far more than they’d paid for them, as investors would be scrambling to buy insurance coverage against the losses on their devalued bonds and CDOs. It was like this group had found a way to purchase dirt-cheap fire insurance coverage on a house that they knew was going to be engulfed in flames the next day.

By detailing how a group of individuals discovered they could profit from the greed and stupidity of some of the world’s leading financial institutions, The Big Short helps us make sense of an event that most of us remember but few fully understand. It’s more than just a story about mortgage-backed securities, credit default swaps, subprime loans, collateralized debt obligations, and systemic risk. At its heart, The Big Short is a tale about the perils of greed and short-sightedness. It exposes the true nature of modern capitalism and forces the reader to seriously question the wisdom of the financial elites who wield so much economic and political power in our society.

Key Themes

The Big Short explores several key themes and enablers of the financial crisis, as well as the human missteps that led to it.

Greed: The Foundation

Above all, greed and short-sightedness were the prime drivers of the financial crisis. The big banks saw that they could get rich by extending mortgage loans to the least-creditworthy Americans and then bundling those loans into complex financial derivatives that they sold off to unwitting and uninformed investors.

In just a few years, these poorly understood financial products spread like a virus throughout the financial system, exposing both Wall Street and Main Street to catastrophic risk. Major players—including the big investment banks, the ratings agencies, insurance companies—all contributed to the creation and proliferation of these dubious financial innovations because they were enormously profitable.

Ordinary homebuyers weren’t inexcusable either—many took on mortgage terms that they had little chance of being able to meet, and some bought multiple houses on meager salaries. While the deceptive nature of how mortgages were marketed played a part in this behavior, consumers were also clearly trying to cash in on skyrocketing housing prices.

In short, all major stakeholders in the ecosystem were fueled by the desire for profit, which made it easy to overlook the other systemic problems below.

Inscrutably Complex Financial Instruments

The sheer complexity of the mortgage-backed securities is what enabled the risk from subprime mortgage bonds and CDOs to spread like wildfire throughout the financial system. No one seemed to understand how these convoluted financial products worked or how to properly evaluate what they were truly worth. Even the big investment banks themselves were confused as to how much of these toxic assets they actually owned.

The ratings agencies were particularly susceptible to these sorts of miscalculations. They were supposed to evaluate the riskiness of these products by assigning ratings to them—these ratings would then be used by investors to determine whether or not they were good investments. Thus, the ratings agencies had enormous influence over the prices that CDOs would command in the marketplace. But the agencies’ ignorance and lack of sophistication led them to assign undeservedly high ratings to the CDOs.

Corruption and Fraud

Explicit corruption and fraud also played a powerful role in creating the crisis. In many cases, the lenders who created the original bad loans that were to be packed into the CDOs deliberately misrepresented the terms of the mortgage to the borrowers. They lured these borrowers in with “teaser rates”—low initial interest rates on their mortgages which then ballooned into exorbitant rates after a few years. This acted as a ticking time bomb in the financial system, triggering a moment where millions of mortgages would fail at the same time.

There were also blatant conflicts of interest that made the subprime mortgage bond market dysfunctional. The ratings agencies already had a poor understanding of the financial products they were meant to be evaluating. But they were also corrupt—they were essentially paid by the big investment banks to issue rosy ratings to the dodgy financial products that the banks were cooking up. The banks were paying clients of the agencies, and the agencies risked losing the banks’ future business if they issued poor ratings to the CDOs.

Profits Encourage Short-Term Thinking

The agencies weren’t the only players who had short-term incentives that encouraged behavior which would be destructive in the long-term. Major insurance companies like AIG prioritized short-term greed over long-term financial stability, because it was highly profitable for them to do so. AIG, for example, insured billions of dollars worth of subprime CDOs, because they were raking in a fortune in insurance premiums. Few at the company bothered to think about what would happen if the underlying bonds failed, because the business was so lucrative in the short-term.

Bad Incentives Drive Bad Behavior

People faced perverse incentives at every level of the subprime mortgage disaster.

Borrowers had an incentive to borrow more than they could ultimately afford because they thought that (with ever-rising home prices) they would always be able to refinance and take out new loans to cover the old ones, using their homes as collateral.

Lenders were motivated to shower uncreditworthy borrowers with cash because they knew that they would just be bundling the loans into subprime mortgage bonds and pass them off to other investors.

The ratings agencies, likewise, had every reason to give their blessing to the whole process because they were being paid by the big investment banks to do so.

And, of course, the big banks themselves got bailed out by the federal government to the tune of $700 billion when the whole market collapsed. This raises another question: did the big banks know that they were too big to fail and that they would receive a bailout no matter what kind of irresponsible risks they took? If so, this would be a powerful incentive to take wild financial risks. After all, it’s easy to gamble when you know you’re playing with the house’s money.

Outsider Perspectives Can See Through the Smoke

Given the madness into which Wall Street had descended, it took a true outsider perspective to see through the smoke and mirrors. It is no coincidence that the group of investors who saw the crisis coming and found a way to profit from it were a collection of cynics, pessimists, oddballs, and neophytes who held no reverence for the supposed wisdom of the market. They were able to see how irrational and chaotic the subprime mortgage bond market was because they had always looked askance at Wall Street’s conventional wisdom. This gave them the necessary perspective to see a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity where no one else could.

Some of them, like Steve Eisman, were morally aghast at Wall Street’s fleecing of ordinary Americans. For others, like Michael Burry, betting against the housing market was simply an extension of the eccentric investing strategy they’d always pursued. But they all had in common the fact that they were iconoclasts and nonconformists who zigged when the rest of Wall Street zagged.

Chapter 1: An Untapped Asset—The Home

The deadly virus that infected the global financial system in 2008 was a relatively new class of asset: the mortgage-backed security. At its most basic level, a mortgage-backed security was a bond, a debt instrument. But it was very different from a traditional bond that might be issued by a government or a corporation. These latter types of bonds were essentially loans, for which the lender would be paid a fixed interest rate over a given period of time until the bond matured and the bondholder received the principal (or “face value” as it’s sometimes known).

Traditional bonds always entailed some level of risk (the company or government from which you purchased your bonds could default, or fall behind on; payment or interest rates could rise and erode the value of your bond on the open market), but these risks were relatively transparent and easy-to-understand for most investors. This was not to be the case with mortgage-backed securities.

Mortgage-Backed Securities

Mortgage-backed securities brought the world of high finance into the lives of everyday Americans—even if they had no idea how much their homes had become chips on the table in the vast casino of global finance. A mortgage-backed security was a bundle of home mortgages (often running into the thousands) that had been packaged together into a tradable asset. When an investor purchased one, she was purchasing the cash flows from the individual home mortgages that made up the security.

This type of asset had actually existed for decades before the global financial meltdown of 2008, though few investors (and even fewer ordinary people) had heard of it. For most of the 1980s and 1990s, it was an obscure corner of the overall bond market, drawing only occasional interest from major financial institutions like Morgan Stanley, Bearn Stearns, and Goldman Sachs.

Many investors at this time, in fact, shied away from them because the cash flows were undesirable. During this era, the bonds were made up of rock-solid mortgages to creditworthy homeowners who were in little risk of default. Ironically, this was the original problem that investors had with these securities. Borrowers could always pay off their mortgages any time they wished, and it was usually easiest for them to do so in a low-interest environment.

Buyers of mortgage-backed securities at this time weren’t concerned about default: they were worried about being paid back too quickly. As an investor, you want to be sitting on cash when interest rates are high so that you can reinvest that money and earn even greater returns. The basic nature of mortgage-backed securities seemed to cut against this basic investing principle. Because people were paying off their mortgages when interest rates were low, the holder of a mortgage-backed security received their money back precisely when it was least valuable to them.

Specialty Finance

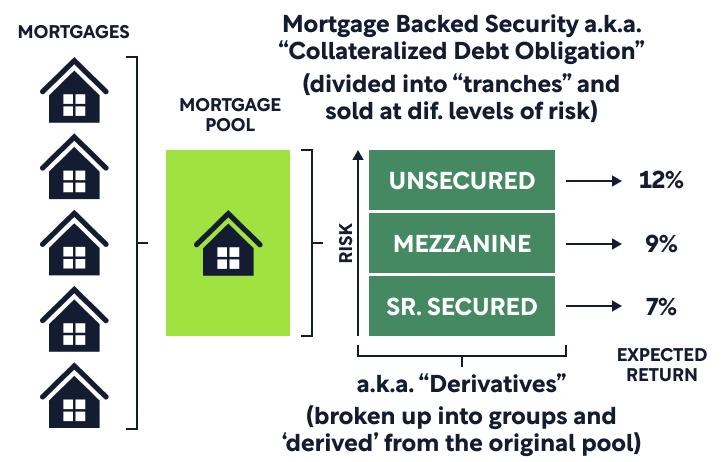

Wall Street, however, had a workaround to this problem. Instead of buying the whole bundle, investors could purchase a slice of the underlying mortgages (or “tranche” as they would become infamously known). Investors in the lowest tranche would receive the first wave of repayments (again, when this cash influx was least valuable). To compensate for the untimely cash flow, these investors would receive a higher interest rate from the bank on the tranche that they purchased.

The tranches ran on a sliding scale all the way to the top. Top-level investors would receive the last wave of mortgage repayments, presumably when interest rates were high and the new influx of cash would be of greatest value. These investors received the lowest rate of interest but enjoyed the security of knowing that they would be getting their money back at the time when it was worth the most.

But this whole structure created a perverse incentive: mortgages made to un-creditworthy borrowers could actually be worth more than mortgages made to qualified borrowers. If your biggest fear as an investor in mortgage-backed securities was that you’d be repaid too early, the last thing you wanted to see in your portfolio was a bunch of financially secure, stable, low-risk mortgages. You wanted high-risk mortgages that stood little chance of being repaid early. Such borrowers wouldn’t qualify for refinancing that would enable them to pay off their mortgages when interest rates fell. They would instead be on the hook for the entire life of the mortgage—making them the ideal borrowers for mortgage-backed security investors.

According to the theory behind these new bonds, even if a few people in the mortgage pool did default (as they invariably would), there were enough other mortgages for the bundle as a whole to be considered diversified—and thus, a safe and profitable investment.

Subprime

In the 1980s and 1990s, a new industry, led by firms like The Money Store, was being established to provide financial products and services to the least-creditworthy Americans. It bore the characteristically euphemistic name of “specialty finance.” The home loans issued to un-creditworthy borrowers became known as subprime mortgages. Although subprime mortgages still only represented a small fraction of the total U.S. credit market at this time, they received a boost from the nation’s growing income inequality. A more skewed income distribution created more and more potential subprime borrowers.

Superficially, the structure of subprime mortgage bonds resembled that of the original mortgage bonds that had been composed of mortgages to creditworthy borrowers. Investors would purchase different tranches, or tiers, of the bonds, only now they were exposed to a much higher risk of actual defaults, because the bonds were composed of subprime mortgages.

Subprime mortgage loan originators were happy to issue loans to almost anybody. Bad credit score? No problem! No income? Nothing to worry about! Past history of delinquency and/or foreclosure? Everyone deserves a second chance!

Home prices seemed to be going up and up with no end in sight. Indeed, the U.S. was living through a period in which the residential housing market had been on a general upward trend since the end of World War Two. The most secure, rock-solid investment appeared to be in homes. For this reason, subprime lenders were largely unconcerned with the risk of default. With the price of their homes always rising, borrowers would always be able to refinance easily. Refinancing simply meant using the equity in one’s home as a form of collateral to obtain a new loan. With this cash, people could pay their original mortgages (thus eliminating the possibility of default) and just take on new debt. It was a way to use a home as a piggy bank, a source of easy cash for over-extended borrowers.

And even if a few borrowers failed to make their mortgage payments on time or couldn’t refinance and obtain a new loan, the lenders would simply take back the house and issue a new mortgage to a new homeowner at an even higher principal, or money owed to the lender.

Moreover, the subprime lenders weren’t keeping the loans on their books. Through mortgage bonds, the loans they had issued to risky borrowers could be bundled, packaged, and sold off to other investors. Any risk of default would be their problem. These incentives contributed to a widespread degradation of lending standards across the mortgage industry.

Ramping Up

Despite the inherent irrationality of the subprime mortgage bond market, it continued to thrive and grow as the 1990s became the early 2000s. In the 1990s, the market was maybe $30 billion: a drop in the ocean of the global credit market. By 2005, there were $625 billion in subprime mortgage loans, $500 billion of which had been packaged into bonds.

Even more alarming, the quality of the underlying loans had only deteriorated over time. Seventy-five percent of the loans by this time were floating-rate or adjustable-rate. This meant that the borrowers received a low “teaser-rate” for the first two years or so of the mortgage, after which they would face rate increases and ever-larger payments (these latter were to become known as “balloon payments”). Of course, this meant that many borrowers would be unable to make their payments in just a few short years, which would, in turn, set off a wave of foreclosures. Although a few foreclosures were no big deal for investors, a large number would wipe out the value of the bonds made up of these mortgages. The time bomb had already been planted.

But the subprime borrowers and the financial institutions still were unable to see what a dangerous game they were playing. A massive game of hot potato was taking hold of the financial system. Lenders had an incentive to make as many subprime loans as possible and immediately sell them off to big Wall Street firms. These firms would then package them into mortgage-backed securities and sell them off to unwitting investors.

The loan originators and the big banks that assembled and sold the bonds were making so much money selling these bonds off to investors that neither really cared about the quality of the underlying loans. The banks pressured the subprime companies to make more and more loans, regardless of the borrowers’ financial position. It became a matter of quantity over quality and volume over value. This was easy to get away with in the unregulated, Wild West world of bond trading. Unlike the relative transparency of the stock market, the bond market was defined by the buying and selling of increasingly complicated financial instruments of which customers had an extremely limited understanding. This gave the bond traders a powerful informational advantage that they exploited to the fullest. The ignorance of the institutional investors who purchased these securities, like pension and retirement funds, was a goldmine for the big banks.

By 2005, the major players on Wall Street, who had once spurned the subprime game because they saw it as too risky, were now eager participants. Increasingly, this market dominated the overall bond market, and because the bond market dominated the dealings of all major investment banks, the subprime market affected the stock market as well. Every financial company had direct or indirect exposure to subprime. The value of their stocks was now inexorably tied up with the performance of highly dubious home mortgages. Subprime was now the tail that wagged the dog.

Steve Eisman: Financial Iconoclast

While the subprime market was growing and coming to cannibalize the wider financial system, an analyst named Steve Eisman was making a name for himself on Wall Street. Eisman had been fascinated by the existence of the subprime market and by the sheer madness of the whole enterprise ever since he’d first become aware of it in the mid-1990s. Originally an attorney, he switched gears relatively early in his career to become an analyst at Oppenheimer, a financial advisement firm.

Eisman rapidly developed a reputation as a brash truth-teller, unwilling to offer up the praise and platitudes that so many financial and banking leaders expected to hear. Wall Street, he saw, was awash in flattery, in which brokers, analysts, and customers told the financial class what it wanted to hear, even when it wasn’t true. Eisman tended to buck conventional wisdom. He was unafraid of telling the truth about the underwhelming performances of the companies he was tasked with analyzing—and telling it loudly.

On one occasion, he delivered a speech at a luncheon in which he lambasted the head of a major U.S. brokerage house (who happened to be in the audience), claiming that this man knew nothing about the business he led. Another time, Eisman crumpled up the financial statements of a Japanese real estate firm and told the CEO that they were “toilet paper.” With his often-unkempt appearance and unrestrained personality, he cut a unique figure among the smartly dressed and cautiously reserved Wall Street set.

But he was also guided by a strong moral compass and began to realize just how much of Wall Street’s business model was based on deceiving the clients whose interests it supposedly existed to serve while gouging working-class Americans out of their homes and savings. He saw these injustices even more acutely after his infant son, Max, passed away in a tragic accident. He saw that bad things could happen to anyone, anywhere, without any warning. This new ability to imagine a worst-case scenario amid a culture of unbridled (and ultimately, unfounded) optimism was to serve Eisman well as the financial sector began to lose all sense of rationality during the 2000s.

The Household Finance Corporation Scandal

The story of the Household Finance Corporation was an early indication to Eisman of just how rotten the lending business had become. In 2002, he obtained sales documents from Home Finance Corporation, a major player in consumer lending that had been founded back in the 19th century.

The sales documents offered borrowers a 15-year, fixed-rate loan, but used language designed to fool customers into thinking it was a thirty-year loan. Customers would think that they had twice as long to pay off their mortgage as they actually did and that they would be making lower monthly payments than they actually owed.

Household did this by “hypothetically” pitching to the customer what their “effective rate” of interest would be if they stretched their 15 years of payments over a 30 year period. The customers were then told that this was their “effective rate” of interest, even though this was entirely fictional. A customer could be bamboozled into thinking she was paying 7 percent interest when she would in fact be paying closer to 12.

To Eisman, this was blatant, even criminal fraud.He tried to sound the alarm about Household, contacting public officials and journalists. But he saw that regulatory officials were unwilling to act to bring Household to heel—the attorney general of the state of Washington even told Eisman that he feared there’d be no other company to make subprime loans in Washington if the state cracked down too hard on fraud.

To Eisman’s dismay, the leadership of Household was never punished—in fact, it was rewarded for its deception. The company settled a class-action suit out of court for $484 million (a fraction of what they had defrauded from customers), then sold itself to HSBC for $15.5 billion. The CEO personally made $100 million on the deal.

The impunity with which the company had acted was a genuine shock to Eisman. The CEO was being showered with wealth, when, in Eisman’s view, they should have “hung him up by his fucking testicles.” It was a revelation to Eisman. The market had not punished bad actors. The incentives had not worked the way they were supposed to. His political views began to shift too, as he started his transformation from a free-market, Reaganite Republican to a progressive, populist, almost socialist Democrat. He now saw the true ethos of the system: “Fuck the poor.”

Chapter 2: Placing the Bet

We’ve seen how the big banks had foolishly hitched their wagons to the subprime mortgage-backed securities market, which suffered from fatal structural weaknesses. But for some savvy investors who saw the mortgage bonds for what they really were, the banks’ short-sightedness represented an unparalleled opportunity. They could bet against Wall Street’s position and reap enormous profits. This was the world of short-selling.

Dr. Michael Burry: An Eye for Value

Dr. Michael Burry was, along with Steve Eisman, skeptical (to say the least) about the confidence with which Wall Street sold mortgage-backed securities. Burry was another outsider to finance, who’d come to Wall Street with an unconventional background and unique life story.

He had lost his eye at the age of two, when it was removed during surgery for a rare form of cancer. He wore a glass eye to replace the one he’d lost. Burry later would observe that this caused him to see the world differently, both literally and figuratively. Perhaps out of self-consciousness, he had trouble with interpersonal relations and thought of himself as something of a loner. To compensate for his social struggles (he would learn much later in life that he suffered from Asberger’s syndrome, a disorder on the autism spectrum), he learned to analyze data with a rigorous eye to detail, seeing patterns that no one else could see.

He was a medical doctor by training, who discovered a knack for investing and stock-picking when he was in medical school in the 1990s after studying the teachings of the legendary investor Warren Buffett. In his spare time (which, as a medical student, was rare) he started a blog on value investing that quickly became a favorite among traders and investment bankers—all of whom were amazed by his aptitude as a newcomer to investing and by the fact that he was doing this while attending medical school. As a value investor, Burry specialized in identifying companies that could be acquired for less than their liquidation value—that is, finding companies that the market was undervaluing. This form of investing was a natural fit for the analytical and unconventional Burry, who saw things that others could not.

The success of his blog established Burry as an acknowledged authority on value investing. Eventually, he quit medical school to pursue a career in finance. Joel Greenblatt of Gotham Capital offered Burry a million dollars to start his own fund, Scion Capital.

Scion was quickly delivering for its clients, no doubt due to Burry’s keen insights about true value and risk. He knew how to beat the market. In 2001, the S&P index fell by nearly 12 percent, but Scion was up 55 percent. In 2002, the S&P fell by over 22 percent, but Scion was up 16 percent. Burry believed that incentives were the driving force behind much of human behavior—and that his rival fund managers had poor ones. Most other managers simply took a 2 percent cut of the total assets under their portfolio, which they earned regardless of how their actually performed. Thus, their incentive was simply to hoard clients’ money, not to take the time and energy to grow that money.

Burry believed this to be inherently unfair. Scion took a different tack, only charging customers for the actual expenses incurred running the fund. Burry insisted on profiting only when his clients profited first.

The Secret Sauce

But what made Burry so successful? How was he able to consistently beat the market by such wide margins? It turns out, he wasn’t really doing anything special. There was no insider trading. He didn’t have secret information or special technology that anyone else on Wall Street didn’t have access to.

He was doing nothing more than buying stocks and analyzing companies’ financial statements. But simply analyzing statements set him apart. No one else was bothering to do the hard, tedious work of actually studying up on the companies they were investing in.

A $100-per-year subscription to 10-K Wizard gave him access to all the corporate financial statements he could ever need. If that didn’t get him what he needed, he would sift through obscure (yet publicly available) court rulings and government regulatory documents to glean valuable nuggets of information that could change the value of companies and markets. He was finding information in places no one else was bothering to look.

Avant! Corporation

A great example of how this paid off for Burry was the story of Avant! Capital. He stumbled upon the company while sifting through court documents to identify firms that had settled lawsuits out of court. He reasoned that having been forced to pay a settlement would be a good, low-key indicator of the kind of company that markets were likely to undervalue.

Avant! had paid $100 million out of court to settle an intellectual property dispute claim. The firm was still bringing in $100 million in revenue and had a workforce composed of Chinese nationals on work visas, who wouldn’t be able to simply abandon ship if the company faced more trouble. Despite these positive trends, however, Burry discovered that the company was only valued at $250 million. Clearly, the market was placing undue weight on the settlement and ignoring the fundamentals.

But where the rest of the investment community saw garbage, Burry saw opportunity. He bought as many shares of Avant! Stock as he could at $12-per-share, and continued to do so as the share price dropped to $2. Of course, this was the exact right time to be buying this stock. He became the company’s largest shareholder and was able to restructure Avant! to inspire new investor confidence. Four months later, the company sold for $22-per-share.

Shorting

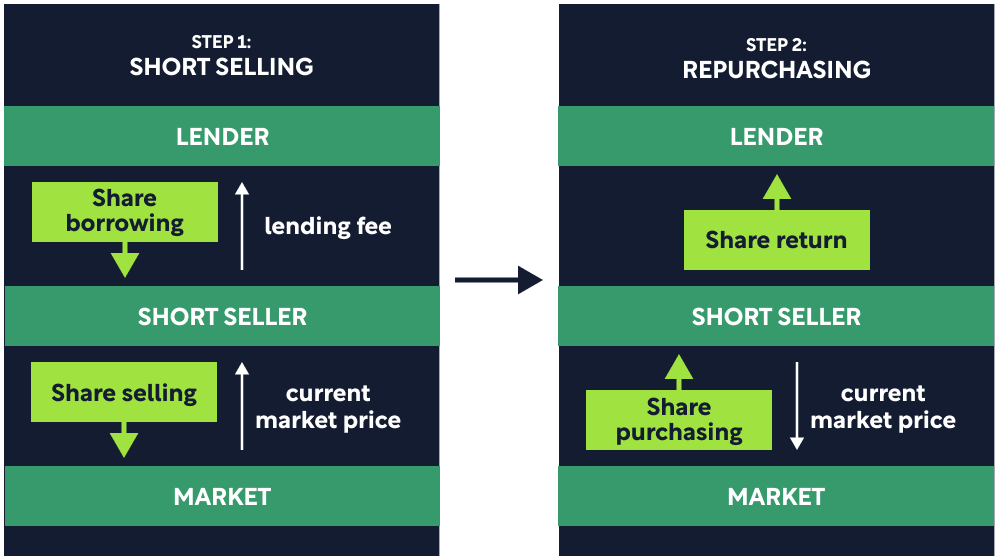

Given this background, Burry saw a rare opportunity in the subprime housing bond market, once again where no one else was looking. But this was a twist on his usual approach. Instead of looking for assets that were undervalued, he was going to target the subprime market because of his conviction that it was extraordinarily overvalued. He was going to short the housing market.

(Shortform note: “Shorting” an asset is a way of placing a bet against it. If you believe, for example, that General Electric is about to sustain major losses, you can acquire borrowed shares of GE stock through your brokerage, with the promise to return those shares at a later, agreed-upon date. If the stock declines in value between when you borrow it and when you must return it, you earn a net profit on the transaction. If you borrow 10 shares of GE when it’s selling for $100 per share and then immediately sell those shares, you pocket $1,000. If they’re selling for $50 each when you need to purchase them in order to return them, your net profit is $500—$1,000 minus the $500 you now need to spend to purchase the stock.

But if the stock has risen in value between when you borrowed the shares and when you must return them, you suffer a net loss on the transaction. If GE is trading at $150 per share when you have to return the stock, your net loss is $500—$1,000 minus the $1,500 you now need to spend to purchase the stock at its higher price.)

Burry had, with characteristic fastidiousness, studied the underlying loans which made up the pool of mortgages being stuffed into the bonds. He saw that borrowers with no income and no documentation were taking up a larger and larger share of the mortgages. Lending standards had collapsed in the face of the market’s insatiable demand for subprime, as loan originators devised more and more elaborate means to justify loaning money to clearly un-creditworthy borrowers. As we’ve seen, these loans were then being repackaged into bonds and sold off by the big banks.

But how would Burry short these types of bonds? Their structure made them impossible to borrow, as the tranches were too small to individually identify. The market didn’t have a mechanism for an investor like Burry, who believed that the subprime mortgage bond market was essentially worthless. But Burry knew a workaround to this problem. He was about to dive into the world of credit default swaps.

Credit Default Swaps

A credit default swap is an insurance policy on a bond. Like most insurance policies, the seller receives regular premium payments for a fixed term, roughly the same as an auto or home insurance policy might work.

For example, if you purchased credit default swaps on $100 million of GE bonds, you might pay $200,000 per year for 10 years. Thus, your losses would be capped at $2 million. But if GE defaulted on those bonds, your payout could be up to $100 million: 50 times what you initially put down. It was a classic asymmetric bet: fixed losses, but potential winnings many multiples over that amount.

Burry saw that now was the time to act. Once the teaser rates on the subprime loans went away and borrowers started getting hit with higher interest rates (in roughly two years), there would be a wave of defaults that would bring the mortgage bond market to its knees. Once that started happening, lots of investors would be desperate to purchase insurance on the bonds they’d invested in—and the only way they would be able to do this would be through the credit default swaps that Burry would own.

But he couldn’t wait too long to buy the swaps. Once the mortgage market started to crumble, the cost of purchasing insurance on subprime mortgage-backed securities would skyrocket, making his trade unfeasible. Timing was key—he needed to corner the market on credit default swaps before the rest of Wall Street caught on, while the swaps could still be had on the cheap.

But there was a hitch in his plan: there were no credit default swaps for subprime mortgage bonds. The banks would have to create them. Furthermore, most of the big firms that would be willing to create them might run into solvency issues and be unable to actually pay Burry the returns on his swaps if his catastrophic predictions were accurate. They were too exposed to subprime. He ruled out Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers as potential credit default swap sellers, reasoning that they were too deep in the subprime game to be able to pay him when the bonds failed.

In 2005, only Deutsche Bank and Goldman Sachs expressed any interest. Burry hammered out a deal with them to establish a pay-as-you-go contract, ensuring payment as individual bonds failed. In May 2005, he purchased $60 million in swaps from Deutsche Bank, $10 million apiece on six separate bonds. Burry hand-picked these bonds after having read the prospectuses, seeing that they were composed of the dodgiest, most questionable subprime loans.

Eventually, he set up a separate fund, called Milton’s Opus, dedicated solely to purchasing credit default swaps on mortgage-backed securities. In October 2005, he told his investors that they now owned roughly $1 billion of such assets. Some investors were outraged that Burry had tied up their money in (what seemed to them) such a risky bet. The U.S. housing market had never collapsed in the way that Burry had predicted. But Burry also knew that a full-on collapse wasn’t necessary for him to reap enormous profits. The way the swaps were structured, he would make a fortune if even a fraction of the mortgage pools went belly-up. The banks barely seemed to understand what they had sold him.

But within months, the market was starting to see the wisdom of Burry’s move. Before the end of 2005, representatives from the trading desks at Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, and Morgan Stanley were asking Burry to sell back the credit default swaps he’d purchased—at very generous prices. Their sudden interest in this financial instrument, which he’d helped them create mere months before, could only mean one thing—the underlying mortgages were starting to fail.

Exercise: Questioning Conventional Wisdom

Think about how wrong popular opinion can be.

Like the investors we’ve met, have you ever been convinced that the conventional wisdom on some topic was wrong? Describe the situation in a few sentences.

Have you ever made poor decisions because something was too complex for you to understand? Elaborate on what happened in a few sentences.

How can you avoid being lured into making decisions like this in the future?

Chapter 3: Doubling Down

By February 2006, many of the savviest players on Wall Street had their eyes on Dr. Burry’s big bet. Other traders were curious why Scion Capital, Burry’s fund, had taken such a dramatic short position against mortgage securities and why Goldman Sachs, in particular, had been so eager to sell him the credit default swaps. What did he know that everyone else didn’t? Greg Lippmann, the head subprime mortgage bond trader at Deutsche Bank, wanted in on the action.

Greg Lippmann: Financial Mercenary

Greg Lippmann was a bond trader with a reputation for being bombastic, crass, and nakedly self-interested. He was known for humble-bragging about how much money he made from his annual bonuses and loudly complaining that he wasn’t being paid enough. Even within the money-obsessed culture of Wall Street, this was beyond-the-pale behavior. Everybody was greedy, but you weren’t supposed to be so transparently greedy.

Although his nominal employer was Deutsche Bank, everyone who met him saw that he had zero loyalty to the bank or its leadership—he was in it purely for himself. This was also something he refused to disguise about himself, openly remarking, “I don’t have any particular allegiance to Deutsche Bank, I just work here.” But his own comically obvious self-interest also made him a keen observer of everyone else’s selfishness and greed. He saw through the phoniness of Wall Street decorum and noticed that everyone was exactly like him.

In early 2006, Lippmann went to Steve Eisman’s office with a proposal to bet against the subprime mortgage market. (As we’ll see in the next chapter, Lippmann couldn’t execute the scheme on his own.) Of course, he had simply copied Burry’s idea, but he presented it to Eisman as his own original strategy. He told Eisman that the underlying loans in the bonds would start to go bad even if housing prices didn’t fall—all they needed to do was stop rising. Borrowers would be unable to refinance using their homes as collateral, which would, in turn, trigger a wave of defaults. Lippmann noted that first-year defaults were already up from one percent to four percent. When the low teaser rates expired, that number would shoot up even more. Indeed, by the end of 2005, Lippmann himself had taken a $1 billion short position against the subprime mortgage bond market.

He also showed Eisman the powerful compelling logic behind the credit default swap bet. You wouldn’t have to pay premium costs for long—most of these nominally 30-year mortgages were really designed to be refinanced and paid off within six years. 30 years became six when low-income Americans couldn’t afford their mortgages after the teaser rate ended and they were forced to refinance. Because the ability to refinance depends on the home’s value, ever-rising home prices meant homeowners would always be able to refinance and borrow more money. If you purchased swaps on $100 million in subprime bonds, your maximum losses would only be the fixed annual premium costs of $2 million per year—$12 million total for six years. But if the default rate rose from 4 to 8 percent, you stood to reap the full face value of the original bond—$100 million.

Finally, despite his skepticism, Eisman did the trade with Lippmann. The logic was sound. Premiums on even the worst subprime bonds were less than two percent of the face value of the referenced bond per year. This was a minor cost compared to what he would earn when the subprime market imploded, which was a certainty. It was spending $2 million to make $100 million.How could he not seize this opportunity?

AIG: Shadow Bank

For Eisman and others to whom Lippmann brought this proposal, it raised an important question: Why had Goldman Sachs been so willing to sell Michael Burry $100 million in credit default swaps? In doing so, they were making a bet that millions of poor and indebted Americans would be able to pay their mortgages on time. No one believed that any major investment bank would be willing to make that stupid a bet, no matter how outwardly confident they were in their subprime mortgage bonds. Goldman couldn’t have been the one left holding the bag. So who was?

The answer was American International Group, Inc. (AIG). The insurance giant was ideally placed to enter the credit default swap market. It was a sterling, blue-chip corporation that—crucially—wasn’t a bank at all. It was an insurance company. And weren’t credit default swaps just another form of insurance?

As a non-bank, AIG could dive into the world of swaps, long-term options, and other risky financial ventures without being subject to bank regulation. It could engage in speculation free from requirements to keep capital reserves against risky assets. It could be on the hook for $100 million in subprime mortgage loans without needing to disclose to regulatory authorities or its shareholders what it was doing. AIG was operating in the shadows of the financial world, where the regulatory spotlight didn’t shine.

AIG began insuring Goldman Sachs’ and Deutsche Bank’s subprime mortgage bonds as quickly as they could get their hands on them. From their point of view, the loan pools were sufficiently diversified that there was little probability of them all failing at the same time. As far as AIG leadership was concerned, the premiums from the credit default swaps were free money. They could only lose if housing prices fell.

AIG, clearly, did not understand the nuances of the business in which it was no knee-deep. AIG was insuring piles of mortgages that it thought were no more than 10 percent subprime—in fact, that figure was over 95 percent. By 2004, AIG was on the hook for $50 billion in triple-B-rated mortgage bonds. They had taken the long position, gambling on destitute American homeowners to pay their mortgages on time.

The CDO: A Masterpiece of Complexity

Clearly, Goldman Sachs was fleecing AIG. The insurance giant seemed to have no idea just how risky the securities that they’d insured actually were.

How did Goldman Sachs achieve this? By creating a masterfully complex and opaque financial instrument known as a collateralized debt obligation (CDO). Essentially, the CDO was a product designed to conceal the true risks of mortgage-backed securities. If you recall, the mortgage-backed security was a bond made up of thousands of loans. The logic was that the bond as a whole was secure, as it was highly unlikely that the underlying mortgages would all tank at once—there was safety in numbers.

The CDO just applied this principle to the bonds themselves. A CDO bundled together the lowest-quality bonds into a whole new tower. It was a bundle of bundles. Bizarrely, the ratings agencies treated this repackaged product as an entirely new financial instrument and slapped a triple-A rating on it (the highest rating that can be given to an asset). We’ll get into why the agencies assigned such high ratings to these dubious financial products later in the summary, but for now, it’s just important to know that these ratings defied market logic and common sense. The CDO wasn’t a new financial product at all—it was just a Frankenstein monster made up of the dodgiest tranches of the original mortgage-backed securities. Yet the ratings agencies treated it as a completely separate portfolio of assets. Apparently, to Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch (the Big Three ratings agencies), the CDO was greater than the sum of its parts.

If this sounds confusing or abstract, that’s because it was supposed to be. Complexity was baked into the design—Goldman Sachs didn’t want customers like AIG to know what they were purchasing or understand the true value of the assets. Opacity was the point.

Synthetic CDOs: Wall Street Alchemy

The issue was compounded even further by the existence of synthetic CDOs. What are synthetic CDOs, and how did they amplify the problem?

An example comes in the shorts that the contrarian investors made. Essentially, Eisman, Burry, and Lippmann’s bets against the subprime mortgage market were more than just simple bets or insurance contracts. They were themselves financial instruments that created their own set of cash flows—the gains they stood to make when the mortgage bonds went bad represented the losses of an actual investor who’d purchased the original bonds. They were, in fact, a near replica of the original mortgage bonds, just with the cash flows going in the opposite direction.

By the very act of purchasing credit default swaps, Eisman, Burry, and Lippmann had created a synthetic mortgage bond—one which could, in turn, be rated by the ratings agencies and packaged off to another round of investors. These investors (like AIG) didn’t know it, but they were essentially making a bet on the outcome of another bet. And the process could replicate itself endlessly. New synthetics could be spawned from the first generation of synthetics. Wall Street didn’t even need to make new subprime loans anymore: through synthetics, they could create new derivatives out of thin air.

Thus, credit default swaps—an insurance product that, in theory, was meant to spread risk around and make the market as a whole more stable—ended up greatly increasing the risk from and exposure to the original mortgage bonds. The synthetics exponentially increased the size of the mortgage bond market. A $10 million CDO could be transformed into $1 billion of synthetics. It was pure speculation and abstraction—at this level, investors weren’t even speculating on actual assets like home loans and home buyers. They were betting on the performance of bets.

Chapter 4: Bubble Nation

Despite Steve Eisman’s keen awareness of how depraved, corrupt, and outright ludicrous the subprime mortgage market was, he still viewed Lippmann with deep suspicion. Lippmann seemed to be a caricature of a sleazy Wall Street bond trader, only out to screw the customer. If it was such a great deal, why was Lippmann offering them a cut of the action?

The answer was that Lippmann needed co-investors like Eisman for his plan to work. While he was confident that his bet against the market would pay off in the long-run, in the short-run, it was expensive. He was sustaining losses on the premiums due on the credit default swaps before the mortgages started failing. He needed other investors to help him share those losses. And, for once, he really wasn’t trying to screw his partners over—they would end up getting rich just like him.

Into the Belly of the Beast

As Eisman dug deeper into the subprime market, he became more and more convinced that Lippmann was right. The market was even worse than he could have possibly imagined. Lending standards, he saw, had deteriorated to the point where lenders were throwing money at people in the bottom 29th percentile of the income distribution—in other words, people who were poorer than 71 percent of the U.S. population!

Eisman and his partners went down to Miami—a flashpoint of the rising default crisis—and saw for themselves empty neighborhoods and subdivisions built entirely through subprime loans. This scene was replicated across the so-called “sand states” of Florida, California, Nevada, and Arizona. The “originate-and-sell” business model of subprime lenders like Long Beach Savings had thrown wads of cash at dubious borrowers, inflating a massive—and largely undetected—housing bubble in the process.

(Shortform note: Housing bubbles occur when the demand for houses increases and supply—the number of houses on the market—can’t keep up with demand. Consequently, home prices increase, sometimes dramatically. The bubble bursts when the tide turns and demand decreases sharply while supply increases—there are more houses available than people who want to buy them. Consequently, home prices plummet.)

The lending standards Eisman saw were obscene. Homeowners with no credit and no proof of income were issued mortgages with no money down. In one instance, a strawberry picker earning $14,000 per year was loaned the money to buy a house worth over $700,000. Eisman even saw the bubble affecting people within his own personal circle. His housekeeper was offered an adjustable-rate, no money down-mortgage to purchase a townhouse in Queens. His daughters’ baby nurse somehow managed to purchase six townhouses in Queens through easy credit. One of his partners even knew a stripper who had five separate home equity loans.

In Eisman’s view, the willingness of borrowers to take out these kinds of loans wasn’t the shocking part. Borrowers had always tried to get as much as they could from creditors. But it had traditionally been the rigid adherence to strict lending standards that had stopped lenders from giving money to obviously un-creditworthy borrowers. Why were they suddenly now so eager to lend money like this?

The answer, of course, lies in the fact that lenders were just repackaging these loans off to the big banks to be sliced and diced into CDOs to be sold to unwitting investors like insurance company AIG. But to truly understand the brewing crisis, we need to understand why mortgage-backed securities were considered so valuable. And for that, we need to look at the ratings agencies.

The Ratings Agencies: Rubber-Stamping Fraud

The credit ratings agencies are supposed to play an important role in the financial system. By evaluating the risks and returns of financial instruments, agencies like Moody’s and S&P help investors determine how much they should pay for these products. The pricing system on Wall Street was inextricably tied up with the grades that the agencies applied to the bonds being sold by firms like Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank. When Moody’s assigned a triple-A rating to a bond composed of worthless subprime mortgages, that bond became worth far more on the market than it really should have been.

Unfortunately, the big investment banks had become experts in playing the ratings agencies for suckers. People who worked at the agencies were widely seen by the big bond traders as second-rate intellects who could be easily manipulated into giving the stamp of approval to complex financial products that they didn’t understand. As one Goldman Sachs trader remarked, “Guys who can’t get a job on Wall Street get a job at Moody’s.”

Traders were surprised to see how easy it was to game the ratings. For example, Moody’s and S&P didn’t evaluate all of the mortgages in the CDOs to see what proportion of them were likely to go bad (and thus, cause the entire bundle to become worthless). All they looked at was the average FICO score (a measure of individual borrowers’ creditworthiness) of the entire portfolio. And a few outliers can always skew an average one way or the other. To be triple-A rated, all the ratings agencies required was that the average FICO score in the entire pool be 615 (still below the U.S. median score of 723).

Moreover, the agencies’ models took no account of the effect of the teaser rates. These models assumed that borrowers would be as likely to pay back their mortgages at an 8 percent teaser rate as they would be at a 12 percent adjustable rate. Of course, this made no sense.

Thick Skulls, Thin Scores

Thus, the investment banks could sprinkle a few high-quality mortgages into a pool of subprime loans and transform the whole package into an investment-grade bond that could be passed on to gullible investors at wildly inflated prices. In allowing this, the ratings agencies muddled the difference between averages and medians. A bond made up of all 615 FICO score loans stood a far lower chance of tanking than did a bond composed of one half 550 scores and another half 680 scores (even though both bonds would have the same “average” score). But the latter is what the agencies were short-sightedly marking up as triple-As.

Furthermore, not all FICO scores were created equal. One borrower’s score of 615might mean something totally different than that of another borrower. The agencies didn’t distinguish between “thin-file” and “thick-file” scores. Thin-file scores referred to those borrowers who had minimal credit history. It was easy to have a high score if you’d never borrowed money in the first place. Immigrants who’d never been given loans before thus had artificially high FICO scores.

And there was every incentive for the original lenders and bond traders to create packages of the worst, most un-creditworthy loans. These mortgages were simply the raw materials that they were using to construct their final products—mortgage-backed securities, credit default swaps, CDOs, and ultimately, synthetic CDOs. And, like any business, they wanted cheap raw materials.

On the Take

But the ratings agencies weren’t just stupid. As Eisman saw, they were corrupt as well. When he and his partners traveled down to Orlando to a subprime mortgage conference, they met with representatives from both Moody’s and S&P.

One woman from Moody’s shocked Eisman’s team with her candor. She had actually done her homework and seen these bonds for the junk that they actually were. But she was told by her bosses that she could not downgrade the bonds.

Although this woman didn’t say so explicitly, the reason was clear—the investment banks hawking these dubious bonds were clients of the ratings agencies. The ratings agencies were for-profit entities paid by the likes of Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank. Of course they weren’t going to alienate a powerful client by slapping a bad rating on one of their premier revenue-generating products.

And the agencies were making a killing. Since going public in 2000, Moody’s had seen its revenues go up from $800 million in 2001 to $2.03 billion in 2006. Most of this increase came from the fees they received from the Wall Street banks for rating CDO deals. This was a booming business, and the ratings agencies weren’t going to put a stop to the party by downgrading the bonds of their powerful clients. Essentially, the agencies were paid to accept the ludicrous assumptions of the finance industry: that home prices would continue to rise and that subprime loan losses would be no more than 5 percent.

Exercise: Examining Greed

Think about how greed and short-sightedness drive bad decisions.

Can you think of an incident from your personal experience in which greed led to a bad decision? Describe the event.

Why do you think the individuals in this case chose to place short-term greed over long-term strategy? What incentives did they have?

Chapter 5: Event-Driven Investing

By fall 2006, Gregg Lippman’s proposal (again, largely copied from Michael Burry’s strategy at Scion Capital) to short the housing market through credit default swaps had made the rounds in the financial world. But he still had few takers. Too many investors, it seemed, were leery about the idea of taking a short position against an asset that major players like Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, and Merrill Lynch seemed so sure about.

Two young, obscure start-up investors, however, heeded the call and saw the opportunity of a lifetime staring them in the face. Charlie Ledley and Jamie Mai had established their (admittedly short)financial careers by betting big on events that Wall Street seemed certain wouldn‘t happen. Profiting off the impending collapse of the subprime market fit perfectly into their theory of how the financial world worked.

Charlie Ledley and Jamie Mai: Garage Band Hedge Fund

Ledley and Mai weren’t career Wall Street guys. They barely had careers at all. Starting their fledgling money management fund, Cornwall Capital Management, with just $110,000 in a Schwab account, they were the sort of bit players that couldn’t even get a phone call returned at Goldman or Merrill. They were scrappers, a “garage band hedge fund.” In fact, they literally started out of a backyard shed in Berkeley, California.

But they had a theory about financial markets that proved to be all too prescient—and that would give them a powerful advantage as the subprime market spun itself into a more and more complex web. Their insight was that investors only understood their own particular slice of the market, whether it was Japanese government bonds or European mid-cap healthcare debt. Everyone was looking at the small picture, the micro. Cornwall’s strategy was to go macro and look at the big picture. With information so unevenly distributed, there had to be pricing mistakes—assets that were priced for far more or far less than they were actually worth, simply because investors didn’t understand what they were actually buying and selling. And that inefficient pricing mechanism could mean big money for the investors who did understand and bought at the right time.

Cornwall’s first test of this theory was with Capital One, a credit card company specializing in issuing credit cards to Americans with poor credit scores. In the early 2000s, their stock had tanked amid fears that they had insufficient capital reserved as collateral to cover the risky credit cards they’d issued. The company soon got into a regulatory dispute with the federal government. The market smelled fraud and investors fled in droves. Despite this, Capital One wasn’t posting unusual losses. Upon speaking with a mid-level corporate manager at Capital One (the only person who would return their phone call), Ledley and Mai discovered that he was buying stock in his own company—not the behavior they’d expect to see from officers at a company engaged in fraud. They determined that Capital One was more or less a sound company, the regulatory dispute was trivial, and that the market was irrationally penalizing them.

For Cornwall, the stock was clearly underpriced at $30-per-share. The best way to profit off this was not to buy the stock itself, but to buy the right to buy the stock at a fixed price for a defined period of time. And the options to buy Capital One stock at $40 for the next 2.5 years cost just over $3 each. It was another asymmetrical bet. If the company really was fraudulent, the stock would be worth nothing and your losses would be capped at $3-per-share of options that you’d bought. But if the company resolved its regulatory issues, the stock would likely jump to $60—double its current price and over 33% more than what you would pay per share once you exercised your options. It was a no-brainer. Cornwall bought $26,000 in Capital One options. When the stock rose, that position was worth $526,000. It was a strategy based upon exploiting the false confidence of other players in the market. They even came up with a name for it: “event-driven investing.”

Getting in the Door

This strategy paid off handsomely for Cornwall. The market for stock options was wildly inefficient. If some external event would cause a stock to be worth either $100 or $0 within a year, it was irrational for an option to buy the stock at $50 to be priced as low as $3. But the market was littered with opportunities like this. Wall Street’s model followed a bell-shaped probability curve for stock prices: it mistakenly believed that a $30-per-share stock was more likely to increase to $35 per share than to $45 per share. It assumed orderliness where there was, in fact, chaos. This was totally at odds with reality. Wall Street seriously underrated tail risk: the ability of extreme events to change asset prices in either direction.

By early 2006, Cornwall had $30 million in the bank. But Ledley and Mai were still small potatoes by Wall Street standards. They might have been high-net worth individuals, but they weren’t institutional investors—they weren’t managing other people’s money, just their own. On Wall Street, they were still second-class citizens. This wasn’t just about recognition or social prestige. Their lowly status denied them the right to trade in the highly complex options—like credit default swaps—being sold through the quantitative trading desks at the big investment banks. There was major money to be made, but Cornwall was locked out of the opportunity. But when they hired Ben Hockett, doors began to open.

Hockett was a former Deutsche Bank trader who’d left Wall Street behind to trade derivatives from the comfort of his home in Berkeley Hills. He wanted to be closer to his family and away from the wild culture of the financial world. He had an apocalyptic streak and was hyper-attuned to the possibility of extreme events. After learning that his house was wildly overpriced and lay on a geological fault line, he immediately sold it and moved into a rental—fearing that he would be hit with the unlikely combination of a housing bubble bursting and an earthquake. This was how Ben Hockett thought about the world.

But for all his eccentricity as both a trader and an individual, Hockett was a respected figure at the major banks. And he knew the right people to get Cornwall’s foot in the door. With a few well-placed phone calls and some meetings, Hockett got Cornwall its ISDA (International Swaps and Derivatives Association) Master Agreement, giving them the right to buy credit default swaps from the likes of Greg Lippmann. They now had a seat at the adult’s table.

Shorting with a Twist

When Ledley, Mai, and Hockett heard Lippmann’s pitch, they recognized credit default swaps as just another type of option, the kind they’d been trading in for years. The market had fantastically underpriced the probability of an extreme event—in this case, the subprime world going up in flames. By October 2006, the doomsday scenario already seemed to be happening. Home prices were falling and borrowers were defaulting. The bonds were already turning sour.

But the team at Cornwall took a slightly different shorting position than did Eisman, Burry, Lippmann, and others. Instead of betting against the lowest tranches of the CDOs, they purchased credit default swaps that enabled them to bet against the highest tranches. Why would they do this? Because they saw that the triple-A bonds were just as vulnerable to collapse as the triple-B bonds, but the swaps against them weren’t priced that way.

As you may recall, the CDOs rated triple-B and those rated triple-A were composed almost entirely of the same types of subprime mortgage bonds, which were in turn made up of the same types of worthless mortgages to low-income Americans. There was no reason to treat them any differently, but the corruption and incompetence of the ratings agencies caused insurance (credit default swaps) on them to be priced as though they were completely different things. A credit default swap on a triple-A CDO cost far less than on a triple-B because the market (irrationally) saw the triple-A as a safer class of asset.

Obviously, these bad loans were all subject to the same economic forces. If one subprime mortgage went bad, they were all likely to go bad. And all that was needed for the entire CDO to collapse was a 7 percent loss in the pools of home loans. Cornwall couldn’t believe the opportunity they were confronted with. On October 16, 2006, they bought $7.5 million worth of credit default swaps from Lippmann’s trading desk, betting against the double-A tranche (one rating below triple-A) of a CDO. Four days later, they bought another $50 million worth from Bear Stearns. Cornwall only needed to spend a fraction of the face value of the referenced CDOs. A small investment in credit default swaps translated to a potential enormous gain once the CDOs collapsed. By February 2007, they owned $205 million worth of credit default swaps against double-A CDO tranches. They had put their chips down.

Chapter 6: House of Sand

By early 2007, Greg Lippmann’s big gamble should have been paying off. Housing prices were falling, defaults were creeping up, but subprime bonds were somehow still standing strong. To him, it was almost as if the market had believed its own lies about the value of these assets.

And Wall Street’s continued delusions about subprime were costing him. With the swaps he’d purchased, he was paying $100 million in premiums, waiting for the bonds to go rotten. He was sure it was a profitable bet in the long-run, but it was costly in the short-run. He needed co-investors like Eisman and the team at Cornwall in order to maintain his position. And even a dyed-in-the-wool market cynic like Steve Eisman was beginning to have his doubts. Lippmann had to act. He had to show Eisman just how arrogant and dumb the people on the other side of their bet truly were.

Sin City

In January 2007, Lippmann flew Eisman and his team out to a giant annual convention of subprime lenders, speculators, and investors, dwarfing the similar convention Eisman had already attended in Miami. Given the excesses and financial hedonism of the subprime industry, the irony of the convention being held in Las Vegas certainly wasn’t lost on Eisman (nor would be the fact that Las Vegas would become ground zero for the housing market meltdown that was shortly to ensue).

Lippmann had Eisman meet a CDO manager named Wing Chau. Eisman hadn’t even known that there was such a thing as a CDO manager (because what was there to manage?), but here was one in the flesh. Chau was a middleman whose job was essentially just to take triple-B tranches of original CDOs (again, themselves composed of subprime mortgage bonds) and repackage them into new towers of bonds. He would then pass them off to unwitting investors like pension funds and insurance companies. And by buying more and more mortgages to immediately repackage and resell, CDO managers like Wang directly contributed to the demand for these bonds and the subprime mortgages of which they were composed. It was like a machine that nobody knew how to turn off.

And, to Eisman’s disgust, Chau was paid obscenely for doing nothing more than shuffling around stacks of useless debt. He received a 0.01 percent fee off the top of the total CDO portfolio he managed, before any of the investors he theoretically served got paid anything (the opposite, if you’ll recall, of Michael Burry’s client-first business model at Scion Capital). This, of course, gave the CDO manager every incentive to grow the pile of CDOs as large as he or she could, no questions asked about the quality of the underlying loans. And 0.01 percent was a lot when you were talking about billions of dollars. In just one year, a CDO manager like Chau could take home $26 million.

Lippmann knew that a figure like Chau embodied everything that Eisman hated about Wall Street. He was arrogant, mediocre, wildly overcompensated, and had his clients’ worst interests at heart. He was a living representation of the dumb wealth that Eisman found so appalling. Meeting Chau was just the sort of boost that Steve Eisman needed to continue shorting the subprime market. Not only did Eisman stand to make lots of money, but he would do so at the expense of the Wing Chaus of the world. That was a powerful enough motivation all by itself. After he left the dinner, Eisman pulled Lippmann aside and told him, “Whatever that guy is buying, I want to short it...I want to short his paper. Sight unseen.”

Troublemakers

Unbeknownst to Eisman, Ledley and Hockett were also in Las Vegas that same weekend. Like Eisman, they were aghast at the lurid spectacle of the subprime convention, and how eagerly investors seemed to be buying these toxic assets.

Everyone they spoke to had the same rationale: these loans had never defaulted in the recent past, so why should they now? They were using the statistically irrelevant past to predict the unknowable future. In fact, they underrated the chance of a catastrophe in the housing market precisely because it would be such a catastrophe. They had deluded themselves into believing that nothing so cataclysmic could actually happen. In thinking this way, they were no different than gamblers riding a “hot streak” at the roulette table, fooling themselves into thinking that the good luck on the last roll of the dice had anything whatsoever to do with what happened on the next roll.

It was a marvelous look inside the sordid world of the subprime mortgage-backed securities business. Eisman, Lippmann, Ledley, and Hockett met all of the key players who did their part to keep this engine of financial doom going—the investment bankers at the big banks selling these poison bonds to unknowing investors, the people at the smaller banks who packaged the loans into those bonds, the intermediaries who reshuffled those bonds into new CDOs, the loan originators, the CDO managers, and the people at the ratings agencies who gave the whole process their stamp of approval.

Eisman earned a reputation as a troublemaker at the convention. He couldn’t help himself when he was surrounded by thousands of (as he saw it) dumb, ethically compromised financial operators who were knowingly scamming the public. At one Q&A session, he harangued the CEO of Option One, a subprime lender known for making loans to particularly un-creditworthy borrowers. Eisman publicly called this man out as a liar, claiming that the default rate in their portfolio of loans wouldn’t be five percent (as the CEO claimed)—it would be far higher, especially once the teaser rates on the loans expired and homeowners got hit with the higher payments on their adjustable-rate mortgages.

Whistling Past the Graveyard

In February 2007, just after the convention in Las Vegas, a publicly traded, triple-B subprime bond index known as the ABX fell by more than a point on the bond markets. It was the first sign to the outside world that all was not well in the housing markets. Yet to the dismay of the short investors, the subprime market kept humming along, as though there was no impending crisis. The big banks seemed to be blithely ignoring the crisis and the ratings agencies refused to revise their positive ratings. The big Wall Street firms were insisting that generic “market sentiment” was driving the value of the bonds down, not the poor quality of the underlying loans themselves. The value of the bonds was completely divorced from the subprime loans underpinning them.

For the short-selling investors, it was as though they’d bought cheap fire insurance on a house that was already on fire. It shouldn’t have been this easy—their swaps were worth far more than they’d been purchased for. This incongruity became even crazier as the subprime bond indexes tumbled even further: by June 2007, CDOs had lost 30 percent of their original value. Ledley and Mai began to suspect that the markets were bluffing their way through the crisis, continuing to sell synthetic CDOs created from the original junk bonds. They had no choice: the banks were all so deep into subprime that they couldn’t afford to change their position.

The complexity of the financial instruments helped the banks continue to fool the markets. No one on Wall Street really understood these products, how they worked, or what was in them. There was total asymmetry of information, with the information mismatch heavily favoring the likes of Goldman Sachs. Thus, the banks were able to dictate the terms of an inefficient market. The prices of CDOs were whatever the banks said they were. Almost nobody had the knowledge (or was willing to do the work) to question this. Even the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), ostensibly Wall Street’s beat cop, had no clue what was going on with these derivatives.

The Contagion Spreads

But the fiction couldn’t be maintained forever. Eventually, the big players on Wall Street began to feel the pain. In June 2007, Bear Stearns announced that it had lost $3.8 billion on subprime mortgage securities. Cornwall should have been delighted, as they had bought most of the credit default swaps from Bear. What was bad news for the investment bank was surely good news for Cornwall. But there was a hitch: Bear had taken such a beating that they might not have the liquidity to actually pay Cornwall the face value of the bonds that the latter had insured.

The exposure to the fallout from subprime wasn’t just limited to Bear Stearns. British bank HSBC also announced in 2007 that they had taken major losses in their subprime lending business. These bonds were like a virus that had infected all of the major financial firms. And given the complexity of the CDOs, very few people inside or outside these firms could tell exactly how much exposure they had to subprime. No one knew for sure just how much of these toxic assets were littered across the balance sheets of the world’s leading financial institutions.

Eisman and his team, in fact, set out to investigate which firms had long positions on subprime (whether these firms knew that they had these positions or not). They called it “the great treasure hunt.” They were looking to take short positions against anyone who had made a bet that the subprime bonds would succeed: in the end, Eisman’s team bought swaps against the banks themselves, the loan originators, and the ratings agencies, fully confident that the whole fraudulent business (as Eisman saw it) would blow up in their faces. In conducting his treasure hunt, Eisman was continually struck by just how foolish and inept so many CEOs at financial institutions really were. The Masters of the Universe were clueless: the emperor had no clothes.

Exercise: Parsing Pessimism

Examine why skeptics and cynics turned out to be the big winners in the financial crisis.

Why were Eisman and the Cornwall Capital team so cynical about the financial system and CDOs specifically?

Explain, in a few sentences, why that cynicism proved to be so useful in predicting the housing crisis.

Is there something about which you’re pessimistic or cynical, but that most people are positive and hopeful? Describe what this is and why you feel so differently.

Chapter 7: Payday

While Eisman, Lippmann, and the Cornwall Capital team were looking into the eye of the coming storm in Las Vegas, Michael Burry was trying to placate his investors at Scion. He was confident that his bet against the housing market would be vindicated. But it was an expensive position to maintain, and one that was costing his wealthy clients significant money in the here and now, as he continued to owe the banks the premiums on the credit default swaps he’d purchased. For the first time, Burry was underperforming the market. In 2006, the S&P had risen by more than 10 percent—Scion had lost 18.4 percent.

Burry was baffled by how the market was behaving. The data from the mortgage servicers kept getting worse and worse as 2006 turned to 2007 (and the teaser rates expired). The loans were faltering at higher and higher rates, yet the price of insuring the bonds composed of these loans kept falling. It was as if a fire insurance policy on a house had become cheaper after the house was on fire. Logic, for once, had failed Dr. Burry. And he was facing an investor revolt, as his clients began to clamor for their money back out of his fund, thinking that he was either a criminal, a madman, or an idiot.

This was a major problem for Dr. Burry. There was language in Burry’s credit default swap contracts with the banks that allowed the major Wall Street firms to cancel their obligations to Burry if his assets fell below a certain level. Thus, even if Scion’s predictions proved to be correct, the big banks could bluff their way through the crisis, maintain high prices for subprime mortgage bonds, run out the clock on Burry, and force him to void his position before he collected a dime. It was imperative to him (and to his investors, though few were convinced) that there not be a mass withdrawal of funds from Scion. They would lose everything, right when they were on the cusp of winning everything.

Side-Pocketing

So what did Burry do? He told his investors, no, they couldn’t have their money back. He exercised a rarely used provision in his contracts with the investors that enabled him to lock up their money if it was invested in assets for which there either was no market or that could not be freely traded. He argued that credit default swaps were just such an asset and that the market for them was either fraudulent or totally dysfunctional. In doing this, he “side-pocketed” his investors’ money, keeping it invested until his bet had fully played out.

But as the aforementioned downturns in the subprime market began in 2007, Scion’s fortunes began to shift, just as Burry had told investors they would. In the first quarter of 2007, Scion was back up by 18 percent. The loans were going bad and borrowers were getting slammed with higher interest payments. The bill was finally coming due for Wall Street.

In just one pool of mortgages that Scion bet against, delinquencies, foreclosures, and bankruptcies rose from 15.6 percent to 37.7 percent from February to June 2007. More than a third of borrowers had defaulted on their loans. The bonds were suddenly worthless. The house was on fire. Investors were scrambling to either sell off these bonds (for a fraction of their original value) or purchase insurance on the bad bets they’d made—insurance that Mike Burry (as well as Eisman, Lippmann, Ledley, Mai, and Hockett) now owned in spades.

Howie Hubler: Hoist by his Own Petard

What went up on Wall Street eventually had to come down. Our collection of oddball investors were about to see their big-time bets pay off—although they didn’t know by whom they would ultimately be paid.

The big banks had made a catastrophic bet, often with upper management not even knowing what its bond trading desks were up to. The story of Howie Hubler, Morgan Stanley’s famed star bond trader, illustrates how the risk from subprime became so diffused throughout Wall Street’s balance sheets.