1-Page Summary

Today we can do amazing things: we can predict hurricanes and tornadoes, we can build skyscrapers of all shapes, and we can save people from heart attacks and severe injuries that would have been fatal a few decades ago.

Yet highly trained, experienced, and capable people regularly make avoidable mistakes. Some can be fatal. After experiencing his own mistakes and observing those of colleagues, Boston surgeon Atul Gawande set out to learn why smart people make avoidable errors and how to prevent them.

The result is The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, in which Gawande proposes a simple solution: a checklist. The book chronicles his exploration of the uses and benefits of checklists in many fields, including aviation, construction, and medicine. While not a how-to manual, his book builds the case for checklists and makes a plea for widespread adoption of checklists as a safety net for human fallibility.

He argues that we fail to get simple things right because in numerous professions — for instance, medicine, engineering, finance, business, and government — the level and complexity of our collective knowledge has exceeded the capacity of any individual to get everything right.

Most professions, especially medicine, have traditionally responded to failure by requiring more training and experience. Training of medical personnel, police, engineers, and others is more extensive than ever. But while training and experience are important, expertise can’t eliminate human fallibility. What’s needed is a different strategy for preventing failure that takes advantage of knowledge and experience but also compensates for human flaws. The solution is a checklist.

Increasing Complexity

To understand how easy it is to make mistakes, despite our ability as humans to accomplish amazing things, consider how complex medicine has become as it has advanced.

An Israeli study several decades ago showed that the average ICU patient required 178 actions or procedures a day. We have a greater-than-ever chance to save someone who’s seriously ill, but it requires both deciding the right treatment and ensuring that 178 tasks are done correctly each day. There’s as much chance to harm a patient as to help.

In complex environments, checklists can help to prevent failure by addressing two problems:

- Our memory and attention to detail fail when we’re distracted by more urgent matters.

- People have a tendency to skip steps even when they remember them.

Checklists protect against failures because they remind you of the minimum necessary steps by spelling them out. They allow you to verify each step while also establishing and instilling a performance standard.

The Aviation Industry Turns to Checklists

In 1935, the Army Air Corps asked airplane manufacturers for a new long-range bomber. Boeing’s Model 299, which exceeded specifications, was favored to win. However, during a flight competition held by the Army in Dayton, Ohio, the Boeing model crashed, killing two crew members.

The plane was much more complicated than previous aircraft — the pilot had many more steps to follow and forgot to release a new locking mechanism on the elevator and rudder controls. To prevent future crashes, Boeing’s test pilots came up with a checklist that fit on an index card, with step-by-step checks for takeoff, landing, and taxiing. Using the checklist, pilots went on to fly the bomber, which became the B-17, 1.8 million miles without incident. Checklists have since become essential in aviation.

World Health Organization Checklist

In 2006, Gawande assisted the World Health Organization (WHO) in solving a problem: Surgery was increasing rapidly worldwide, but surgical patients were getting unsafe care so often that surgery was a public danger. WHO needed a global program that would reduce avoidable harm and deaths from surgery.

Gawande and his team came up with a 19-point checklist. Results of a pilot study at eight hospitals worldwide using the Safe Surgery Checklist exceeded expectations:

- Rates of major complications for surgical patients in all eight hospitals fell by 36 percent. Deaths fell 47 percent.

- Infections fell by almost half.

- The number of patients having to return to the OR because of problems fell by a quarter.

Since the results of the WHO checklist were published, more than a dozen countries pledged to implement checklists. By the end of 2009, about 10 percent of U.S. hospitals and 2,000 worldwide had implemented or pledged to implement the checklist.

Creating a Checklist

Boeing’s flight deck designer, Daniel Boorman, is an expert on checklists. Before creating a checklist, he recommends two things:

1) Define a clear ‘“pause point” or logical break in the workflow at which the checklist is to be used.

2) Decide whether to create a Do-Confirm list or a Read-Do list.

To use a Do-Confirm checklist, team members perform their jobs from memory. Then they stop and go through the checklist and confirm that everything that was supposed to be done was done. To use a Read-Do checklist, people carry out the tasks as they read them off, like a recipe.

Once you’ve chosen the type of checklist, follow these guidelines:

- Keep the checklist short, typically five to nine items.

- Focus on the “killer” items or steps that are most dangerous to miss.

- Keep the wording simple and exact.

- Use language and terminology familiar to the user.

- Fit the checklist on one page.

- Test your checklist in the real world — have people use it and provide feedback.

Hero With a Checklist

On Jan. 25, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549 left La Guardia Airport with155 passengers on board, hit a flock of geese, lost both engines, and crash-landed in the icy Hudson River. Investigators later called it the most successful ditching in aviation history. Pilot Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger III was hailed as a hero.

But Sullenberger emphasized repeatedly that it was a team effort. The 155 people on board were saved by something much bigger than individual heroism and skill. It was the crew’s ability to follow vital procedures (checklists) in a crisis, stay calm, communicate, and function as a team. This is the definition of heroism in the modern era.

Checklists don’t replace the need for skill, boldness, and courage — they enhance these qualities by improving focus, making sure you have critical information when you need it, facilitating communication and teamwork, and minimizing human error.

Introduction

In the 21st century, we can do things that were unthinkable not long ago. We can predict hurricanes and tornadoes, we can build skyscrapers and buildings of all shapes, and we can save people from heart attacks and severe injuries that would have been fatal a few decades ago.

Yet highly trained, experienced, and capable people regularly make avoidable mistakes. Some can be fatal. After experiencing his own mistakes and observing those of colleagues, Boston surgeon Atul Gawande set out to learn why smart people make avoidable errors and, more importantly, to find a way to prevent them. The result is The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, in which Gawande proposes a simple solution: a checklist.

In a 1970s essay on human fallibility, Samuel Gorovitz and Alasdair MacIntyre argued that in some cases we fail due to “necessary fallibility” — because we’re trying to do something humans are incapable of. Much of the universe is unknown to us; there are limits to what we can know and do.

Yet we also fail frequently in areas where we have control. Gorovitz and MacIntyre argued there are two reasons:

- Ignorance or lack of knowledge.

- Ineptitude, meaning we have the knowledge, but don't apply it correctly.

Mistakes due to ignorance can be addressed with more education and experience. But knowledge doesn’t make a difference if we fail to apply it or do so incorrectly. An experienced meteorologist can miss signs of a storm’s likely behavior, or a skilled doctor can forget to ask a patient a critical question.

Ineptitude in Action

Surgeons like Gawande often tell each other stories of mistakes and near misses, puzzling over how they could have missed seeing something that turned out to be vital. For instance, a surgeon friend told Gawande s story about treating a drunken patient with a stab wound received at a Halloween costume party. The emergency department determined the two-inch-wide abdominal wound wasn’t an extreme injury although he needed surgery, so they parked the patient while the operating room was readied.

Then a nurse noticed his condition was deteriorating. They began life-saving measures and rushed him immediately to the operating room, where they discovered that the man’s stab wound went 12 inches into his body, right into the aorta. With great effort, they managed to save him.

In the process of assessing the patient, the team had gotten almost everything right, but they’d forgotten to ask what he’d been stabbed with, which would have indicated the severity of the injury. A party-goer dressed as a soldier had stabbed him with a bayonet.

In another case, the same surgeon was removing a cancer of the stomach when, about halfway through the procedure, the patient’s heart stopped. The team couldn’t find any cause as they worked to resuscitate him and called for additional personnel and equipment. A senior anesthesiologist who’d been in the room earlier, before the patient had been put to sleep, arrived to help. He asked the attending anesthesiologist if he’d done anything additional since they’d last spoken. The doctor said yes, he’d given the patient potassium when lab reports arrived showing his levels were too low.

When the team dug the IV bag out of the trash, they discovered that the patient had been given the wrong concentration — a lethal dose. Through a variety of heroics, they managed to bring him back. The team was shaken: they’d had all the necessary knowledge and tools, but their ineptitude nearly killed him.

An Explosion of Knowledge and Complexity

In trying to do the right things, the challenge of the 21st century is ineptitude, rather than ignorance. It used to be the reverse. For most of human history, we struggled with scientific ignorance. We didn’t understand how things worked or what caused illnesses and how to treat them.

For instance, doctors didn’t know how to treat heart attacks or how to prevent them as recently as the 1950s. Patients were prescribed morphine and bed rest and, if they survived, they lived as invalids. Today, however, we have a host of treatments and procedures that save lives and limit heart damage. Also, we can prevent many heart attacks because we understand and can mitigate the risks of high blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking, and diabetes.

But while science has increased our knowledge dramatically, we still often fail. The reason isn’t lack of money, malpractice, or government or insurance issues. It’s the enormous and ever-increasing complexity of many fields today. We struggle to apply knowledge the right way at the right moment. Under pressure, we make simple mistakes and overlook the obvious.

For instance, authorities at all levels make numerous mistakes when disasters strike. Attorneys make mistakes in complex legal cases, most commonly administrative errors. We have foreign intelligence failures, cascading banking industry failures, and software design flaws that compromise the personal information of millions of people. Deciding the right treatment among the many options for a heart attack patient can be extremely difficult. Each one involves complexities and pitfalls.

Getting the right thing done is a challenge too. From research, we know that heart attack patients who will benefit from cardiac balloon therapy should have it within 90 minutes of arriving at a hospital. After that, survival rates drop. But a 2006 study showed less than a 50 percent likelihood that a medical staff could get everything done that needed to be done in less than 90 minutes. Similarly, at least 30 percent of stroke patients get insufficient care, and the same is true for 45 percent of asthma patients and 60 percent of pneumonia patients. Knowing the right steps and trying hard aren’t enough.

A Different Strategy

Those on the receiving end of such failures naturally react with outrage. We can forgive ignorance and accept that others tried their best with what they knew. But when the experts know what to do and fail to do it, we’re likely to blame gross negligence, incompetence, or heartlessness. This ignores the complexity of many jobs today.

The problem is that across numerous professions — medicine, engineering, finance, business, government — the level and complexity of our knowledge is more than any individual can apply correctly in all circumstances. Knowledge has saved and also overwhelmed us.

Most professions, especially medicine, have traditionally responded to failure by requiring more training and experience. Training of medical personnel, police, engineers, and others is more extensive than ever. Due to increased training requirements, doctors don’t practice independently until their mid-thirties. But while training and experience are important, expertise doesn’t address human fallibility. We need a different strategy for preventing failure that takes advantage of knowledge and experience but also compensates for human flaws.

The solution is a simple checklist.

Chapter 1: Managing Extreme Complexity

To understand how easy it is to make mistakes, despite our ability as humans to accomplish amazing things, consider how complex medicine as become.

The World Health Organization’s international classification of diseases (ninth edition) lists over 13,000 different diseases, syndromes, and injuries. There are treatments for nearly all of them, but there are different, complicated steps for handling each one. Doctors can choose among more than 6,000 drugs and 4,000 medical and surgical procedures.

A Boston clinic affiliated with Gawande’s hospital began with a straightforward goal in 1969: to provide the full range of outpatient services its patients might need throughout their lives. Delivering that care led to the construction of more than twenty facilities and the employment of six hundred doctors and one thousand other health professionals covering fifty-nine specialties.

In a typical year, each doctor at the clinic evaluated an average of two hundred and fifty different diseases and conditions in patients who had more than 900 other medical issues. Each doctor prescribed some three hundred medications, ordered more than a hundred different tests, and performed an average of forty different kinds of office procedures. With new genetic findings, types of cancer, diagnoses, and treatments being developed constantly, electronic records systems can’t keep up, and many diagnoses have to be listed as “other.”

More Opportunity for Error

Hospital care is increasingly complex as well, especially critical care performed in intensive care units or ICUs. Fifty years ago, ICUs were uncommon. Today, thanks to our ability to save people from so many things that were once fatal, critical care is an increasingly large part of what hospitals do. Over a normal lifespan, most people will end up in an ICU at some point.

An Israeli study several decades ago showed that the average ICU patient required 178 actions or procedures a day. We have a greater chance than ever before to save someone who’s seriously ill or injured, but it requires both deciding the right treatment and ensuring that 178 tasks, encompassing various individual steps, are done correctly each day. There’s as much chance to harm a patient as to help. For instance, with all the tubes required, there are myriad ways to introduce infection. In fact, about half of ICU patients end up with a serious complication.

An increasing number of training programs focus on critical care; about half of all hospitals now have intensive care specialists, called intensivists. But with the increasing complexity of medicine, even specialization can’t keep up. So, in addition to specialists, we have superspecialists, who study and practice one thing, like laparoscopic surgery or pediatric genetic diseases. They have greater knowledge and ability to handle the complexities of a particular job, but they haven’t managed to avoid making mistakes.

Surgery is perhaps the most specialized area in medicine. An operating room has an array of specialists. For instance, there are many kinds of anesthesiologists — for instance, one type focuses on pain control. There are also pediatric, cardiac, obstetric, and neurosurgical anesthesiologists.

Surgeons are highly specialized to the point that they joke about “right ear” and “left ear” surgeons. General surgeons are becoming obsolete and specialties are rapidly dividing into subspecialties.

We’ve seen great advances in surgery, but with greater specialization and more surgery being done — Americans average seven operations in a lifetime — the opportunity for harm also is great. In the U.S. there are three times as many deaths following surgery as there are from traffic accidents. Research shows that at least half the deaths and major complications are avoidable.

The medical profession has tremendous knowledge, but despite extreme specialization and training, practitioners still miss important steps and make mistakes. When superspecialization of medicine isn’t enough, it’s time to look more widely for answers.

Chapter 2. The Benefits of Checklists

In complex environments, checklists can help to prevent failure by addressing two problems:

1) Our memory and our attention to detail fail when we’re distracted by more urgent matters. For instance, if you’re a nurse, you might forget to take a patient’s pulse when she’s throwing up, a family member is asking questions, and you’re being paged.

Forgetfulness and distraction are especially risky in what engineers call all-or-none processes, where if you miss one key thing, you fail at the task. For instance, if you go to the store to buy ingredients for a cake and forget to buy eggs, you can’t make the recipe because it wouldn’t work without eggs. The consequences are more serious if a pilot misses a step during take-off or a doctor misses the key symptom.

2) People have a tendency to skip steps even when they remember them. In complex processes, certain steps don’t always matter, so people may play the odds and skip them. For instance, if measuring all four of a patient’s vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, temperature, and respiration) only rarely detects a problem, you might become lax about checking everything.

Checklists protect against such failures because they remind you of the minimum necessary steps by spelling them out. They allow you to verify each step while also establishing and instilling a performance standard.

Boeing Discovers Checklists

In 1935, the Army Air Corps asked airplane manufacturers for a new long-range bomber. Boeing’s Model 299, which exceeded specifications, was favored over models by Martin and Douglas. However, during a flight competition held by the Army in Dayton, Ohio, the Boeing model stalled at 300 feet and crashed, killing two of five crew members.

The plane was much more complicated than previous aircraft — the pilot had more steps to follow and forgot to release a new locking mechanism on the elevator and rudder controls. After the accident, a newspaper called the new model “too much airplane for one man to fly.” The Army Air Corps chose Douglas’s smaller design, and Boeing took a big financial hit.

Nonetheless, the Army bought a few Model 299s as test planes and a group of test pilots studied how to prevent future pilot errors. Instead of focusing on requiring longer training, they came up with a pilot’s checklist. Flying up to that point had not been especially complicated, but flying the new plane required too many details to be left to memory.

The test pilots made their checklist simple, clear, and concise — it fit on an index card — with step-by-step checks for takeoff, landing, and taxiing. Using the checklist, pilots went on to fly the bomber, which became the B-17 Flying Fortress, 1.8 million miles without incident. The Army ordered 13,000, and the bomber gave the allies a big air advantage in World War II.

Checklists have become essential in aviation, averting problems and accidents. In notebook and electronic forms, they’re a standard and crucial part of pilot training and aircraft operation.

Medical Checklists

In medicine, the four vital signs mentioned above (pulse, blood pressure, temperature, and respiration) have become an important regular check on how a patient is doing. Missing one can be dangerous.

Medical practitioners didn’t consistently measure and record the four vital signs until the 1960s, when nurses in Western hospitals designed patient charts that included them. Checking them off on a chart was a way of ensuring that in a busy and demanding environment, they wouldn’t forget to make the checks every six hours. Hospitals have since added a fifth vital sign, the patient’s pain level on a scale of one to ten.

In 2001, a critical care specialist at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Peter Pronovost, decided to try a checklist for doctors, targeting a common problem in ICUs: central line infections. A central line is a type of catheter placed in a large vein that allows multiple IV fluids to be given and blood to be drawn. Pronovost’s checklist listed the steps for avoiding infections:

- Wash your hands with soap.

- Clean the patient’s skin with antiseptic.

- Put a sterile drape over the patient.

- Wear a mask, hat, sterile gown, and gloves.

- Put a sterile dressing over the insertion line.

He asked nurses to watch doctors put lines in patients for a month and note and how often they carried out each step. More than a third of the time, doctors skipped at least one step. He then enlisted the hospital administration to authorize nurses to stop doctors if they skipped a step on the checklist.

Over a year, the line infection rate dropped from 11 percent to zero. Over 15 more months, there were only two line infections. Pronovost calculated that at just a single hospital, the checklist had prevented 43 infections and eight deaths and saved $2 million.

Building on Success

Pronovost tested more checklists in the Johns Hopkins ICU. For instance, his team created a checklist to ensure nurses checked patients for pain at least once every four hours and provided medication if necessary. The number of patients suffering untreated pain dropped from 41 percent to 3 percent.

They created another checklist for patients on mechanical ventilation or breathing assistance. Steps included making sure they received an antacid and propping up the head of the bed. The proportion of patients not receiving the specified care fell from 70 percent to 4 percent, incidence of pneumonias dropped by a quarter, and 21 fewer patients died than in the previous year.

Pronovost’s teams also found that care improved when they had doctors and nurses in the ICU create their own checklists for what should be done. The average length of stay in the ICU declined by half.

These checklists helped jog their memory and established the importance of basic steps, which even experienced staff had overlooked. They also set a higher standard for performance. For instance, before the ventilator checklist was implemented, half of the ICU staff hadn’t realized the importance of giving patients antacid medication.

Statewide Implementation

In 2003, Michigan Health and Hospital Association implemented Pronovost’s central line checklist throughout the state’s ICUs; it became known as the Keystone Initiative.

As part of the implementation process, each hospital assigned a senior hospital executive to hear staff concerns and help to solve problems. Executives learned that the right soap, shown to reduce line infections, wasn’t available in more than two-thirds of ICUs. They quickly provided the soap to all Michigan ICUs. Other important supplies that were often unavailable were provided as well.

In 2006, the Keystone Initiative published its findings in a landmark article in the New England Journal of Medicine. Within the first three months of using the checklist, the central line infection rate dropped by 66 percent. In terms of infection rates, the average ICU in Michigan did better than 90 percent of ICUs nationwide. In the first eighteen months, hospitals saved an estimated $175 million and more than 1,500 lives.

Miracle in Austria

Checklists have saved lives around the world. In 2001, a medical journal reported the recovery of a three-year-old girl who fell into an icy pond in a small town in Austria. It took her parents thirty minutes to find her, pull her out, and start CPR, while on the phone with EMTs. When rescue personnel arrived, they continued CPR and a helicopter got her to a small hospital, where staff put her on a heart-lung bypass machine and took her directly to the OR. At the two-hour mark, her heart began to beat and in six hours her temperature, which had been 66, reached normal. She had lung damage and brain swelling, but was able to go home in two weeks. She completely recovered by age 5.

The medical staff had pulled off something hugely complicated. Dozens of people had to carry out many steps correctly and in the right order. Usually, patients in such cases don’t survive. The hospital had previously lost drowning victims and had devised a new system in hopes of saving lives in the future.

They succeeded with the help of a checklist. Under the leadership of the cardiac surgeon, they had made a checklist, designating key roles for the rescue squads and the hospital telephone operator. For instance, rescue teams were to alert the hospital to prepare for a possible cardiac bypass before they even arrived on the rescue scene to allow preparation to get underway. The telephone operator would then notify a list of people to have everything set up. With the checklist in place, the team’s first success was the rescue of the little girl. Two other such rescues followed.

Chapter 3: From Simple to Complex

The successful experiences of using checklists in aviation decades ago suggest they could be applied widely. They protect even the most experienced from making mistakes in a whole range of tasks. They provide a mental safety net against typical human lapses in memory, focus, and attention to detail.

Professors Brenda Zimmerman and Sholom Glouberman, who study complexity, defined three kinds of problems: simple, complicated, and complex.

- Simple: An example of a simple problem is baking a cake from a mix — there’s a recipe and a few techniques, but once you’ve learned them, following the recipe usually works.

- Complicated: An example of a complicated problem is sending a rocket to the moon. Complicated problems can be broken down into smaller problems. Solving the problem involves many people, teams, and specialists. Unexpected issues pop up, but you can learn, repeat the process, and perfect it. Timing and coordination are key.

- Complex: An example of a complex problem is raising a child. Every child is unique. You learn from raising one child, but the next child may require a different approach. With complex problems like raising a child, the outcome is uncertain. Yet it’s possible to raise a child successfully.

In classifying the three problems described so far in this book — the bomber crash of 1935, the issue of central line infections, and the rescue of a drowning victim — the key problem and solution in each case were simple:

- To avoid crashing the bomber, focus on the rudder and elevator controls.

- To reduce central line infections, maintain sterility.

- To saving a drowning victim, be ready to perform a cardiac bypass

All could be resolved by using a simple tool to compel the needed behavior — a checklist. We’re constantly confronted with similar simple problems that can be mitigated by checklists — for instance, a nurse’s failure to wear a mask while putting in a central line or a surgeon’s failure to recall that one cause of a cardiac arrest could be a potassium overdose.

But can checklists be used to address complicated or complex problems, such as ICU work, where there are many tasks performed by multiple people, dealing with individual patients with individual and complex problems? Medicine encompasses all three types of problems — simple, complicated, and complex. It’s important to get basic things right, while allowing skill, judgment, and ability to react to the unexpected.

The medical profession could learn from the construction industry, which handles the design and construction of huge and complicated structures with the help of sophisticated checklists addressing the full range of problems.

Demise of the Master Builder

People used to hire master builders, who designed, engineered, and oversaw the construction of large and small projects from start to finish. For instance, master builders built Notre Dame and the U.S. Capitol building.

However, by the mid-20th-century master builders became obsolete because one person alone couldn’t master the advances occurring at every stage of the construction process. Architectural design and engineering design became separate specialties. Other specialties and subspecialties developed. Builders split further into areas of expertise such as finish carpenters and tower crane operators. Major projects now involve 16 different trades and hundreds of workers who must do their jobs in coordination with others.

The construction process is orchestrated using sophisticated schedules and checkpoints that enforce roles, communication, and follow-through. The major advance in the industry over the last few decades has been perfecting this process of tracking and communication.

To manage increased complexity, the entire construction industry was forced to evolve. However, much of medicine is still structured like the master-builder era — with a lone physician executing all of a patient’s care — even though times have changed to the extent that a third of patients have at least 10 doctors involved in their care by the last year of their life. As a result, care can be uncoordinated and subject to error.

In construction, failure isn’t an option. Massive structures must stand up straight and withstand all kinds of pressures and potential disasters such as fires and earthquakes.

The Rise of the Construction Checklist

To see how this works, the author visited the Russian Wharf project in Boston while it was under construction in 2006. The project, completed in 2011, consisted of a high-rise, glass-and-steel waterfront building that incorporated commercial and residential space while retaining historic aspects of the original building on the site.

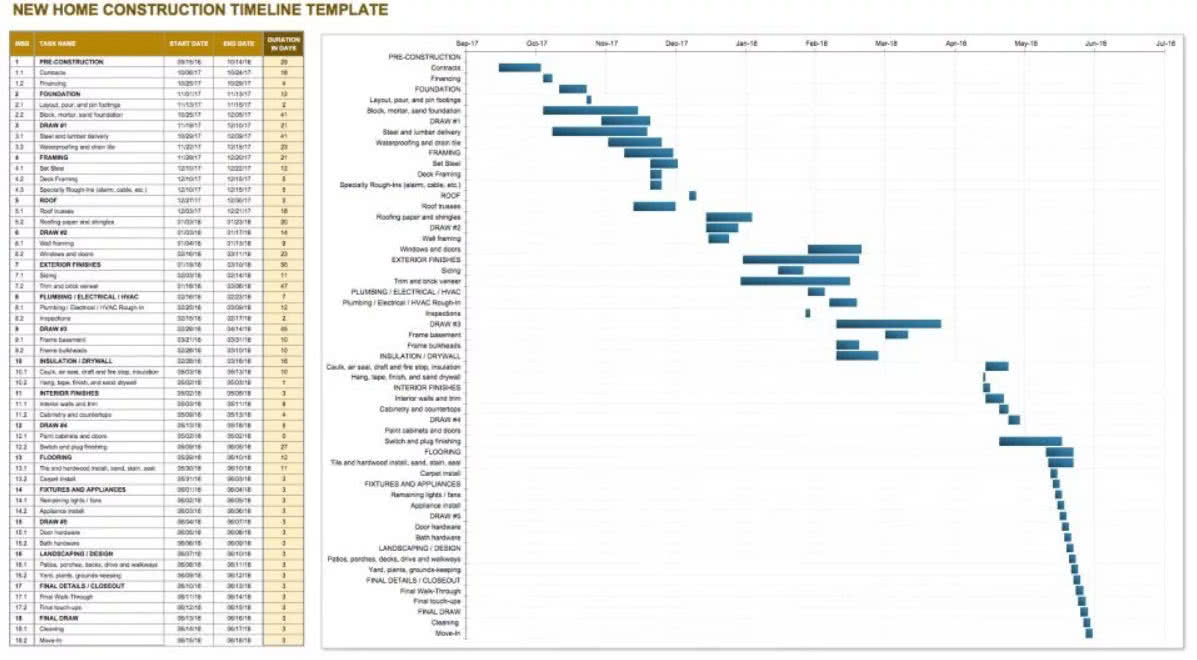

The nerve center for the project was a room where the construction schedule, essentially a huge checklist, was posted on the wall. This consisted of multiple, large sheets of paper containing numerous computer-created, color-coded lists. They listed every task by order and date — for instance concrete pouring and steel delivery for each story were scheduled at certain times. As each task was completed, the project executive noted it on the schedule and printed out the next phase of work. The construction schedule was designed to build the project in layers, using day-by-day checks to ensure that the knowledge and skills of hundreds of people were correctly applied at the right time and place.

(Shortform example: above, an example construction schedule.)

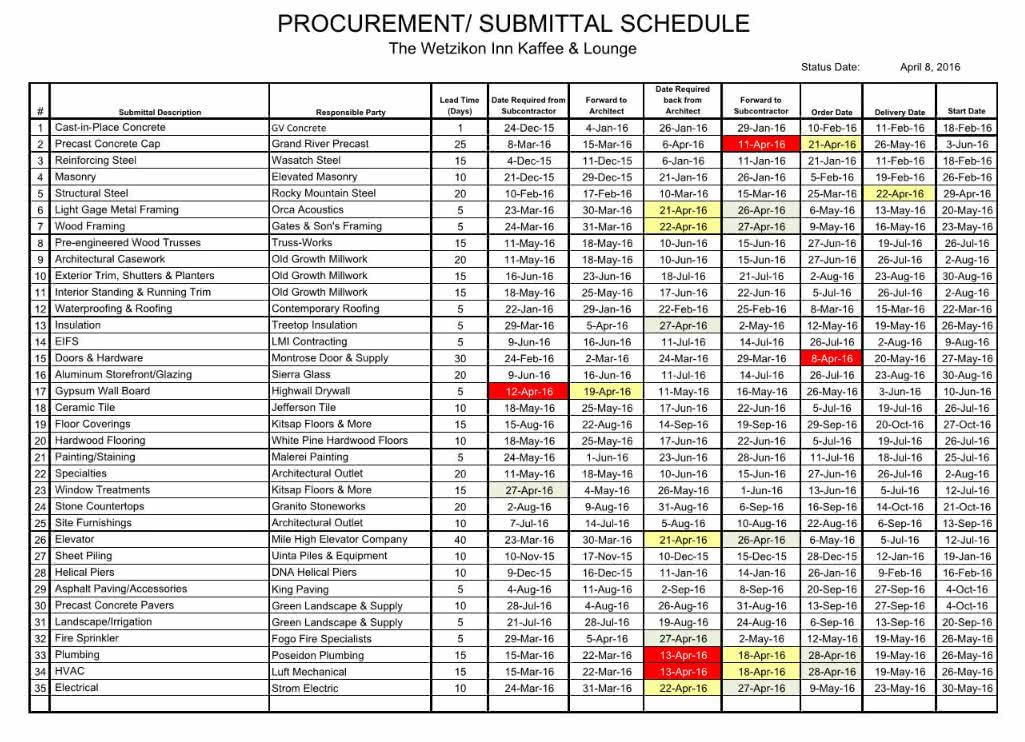

A second type of schedule, called a submittal schedule, specified when people were to communicate, about what, and with whom. The submittal schedule dictated that various experts speak to each other on specific dates regarding progress in specific areas, as well as who needed to share, or submit, information before the next steps could proceed.

Besides maintaining communication, the submittal schedule was a means of handling unexpected developments. Experts could make judgments, but they had to discuss problems with a team, taking others’ concerns into account and agreeing on what to do.

(Shortform example: above, an example submittal schedule.)

The submittal schedule operated on the assumption that if you got the right people talking to each other, problems could be averted or addressed. To deal with the unexpected, the builders relied on communication and group knowledge, rather than the expertise of an individual.

Success Built on Communication

The reason for the construction industry’s emphasis on communication is that failure to communicate is the most common reason for major building errors.

For example, there was a serious communication oversight in the construction of the Citicorp building, now called The Citigroup Center, in Manhattan. It features an unusual design — a slanted top and a nine-story stilt-style base. During its construction in the 1970s, the welding contractor building the base changed specifications without consulting the architects — the contractor switched from making welded joints to less-strong bolted joints, which could have failed and caused the building to collapse in 75 mile-per-hour winds.

The architect discovered the change in 1978, a year after the building opened, when he reviewed the plans in response to a question from a Princeton engineering student. He informed the building’s owners and not long afterward, Hurricane Ella began moving up the coast toward the city. An emergency crew worked secretly at night to weld two-inch-thick steel plates around two hundred bolts to successfully secure the building.

While the construction industry’s checklist process hasn’t been perfect, it’s been amazingly successful. Building failures are extremely unusual. And although buildings are more complex than ever, and are built to higher standards for such things as earthquakes and energy efficiency, they take a third less time to build.

Chapter 4: Empowerment and Checklists

A striking feature of the building industry’s strategy for handling myriad steps correctly in complex situations is empowerment.

That’s not the way complexity and risk are usually handled elsewhere. Most authorities centralize power and decision-making via a command-and-control model. That’s one way of using checklists: to dictate instructions to workers down the line so they do things in a prescribed way.

A construction schedule checklist works that way — but it’s paired with the submittal schedule (the one that establishes communication processes), which is based on a different philosophy of power for solving non-routine problems. The submittal schedule pushes decision-making out from the center. People have the ability to make their own judgments based on their experience and expertise, but they’re required to communicate with others and take responsibility.

For example, because determining whether every detail is correct requires more knowledge than any one person can possess, building inspectors mostly make sure that builders have the right checks in place and require them to sign affidavits attesting that they have ensured the structure meets code requirements. They spread the authority and responsibility.

Why Empowerment is Important

When authorities don’t relinquish power in a complex situation, they’re likely to fail. The response when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans on Aug. 29, 2005 illustrates both how centralized power fails and how empowerment works in such situations.

(Shortform note: While the Katrina example doesn’t demonstrate the use of checklists, it suggests why incorporating empowerment and communication into checklists, as the building industry does, is key to checklists’ success.)

Initial reports after the hurricane made landfall in New Orleans at 6 a.m. were falsely reassuring because, with power and cell service down, they were extremely incomplete. Director Michael Brown and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) announced the situation was mostly under control.

But by afternoon the levees had been breached and 80 percent of the city was flooded; 20,000 people were stranded at the Superdome, 20,000 were at a convention center, and another 5,000 had been deposited on an overpass by rescue helicopters. Tens of thousands were stranded in attics and on rooftops.

The government’s command-and-control system became overwhelmed, with too many decisions to make and too little information available. But authorities clung to the traditional model. They argued with state and local government officials over the power to make decisions, resulting in chaos. Supply trucks were halted and requisitions for buses were held up while local transit buses sat idle.

Wal-Mart executives, however, took the opposite approach from command and control. Recognizing the complexity of the circumstances, CEO Lee Scott announced to managers and employees that the company would respond at the level of the disaster. He empowered local employees to make the best decisions they could.

Within 48 hours, employees had gotten more than half the 126 damaged stores up and running, and they began providing help wherever they saw needs — for instance, distributing diapers, water, baby formula, and ice. While FEMA couldn’t figure out how to move supplies, Wal-Mart managers created paper credit systems for first responders, providing them with food and supplies.

Individuals felt empowered to make their own decisions. The assistant manager of a severely flooded store drove a bulldozer through it, loaded up everything useable, and gave it away in the parking lot. When she learned that a local hospital was running out of drugs, she broke into the store’s pharmacy to get what the hospital needed.

Meanwhile, instead of issuing instructions, senior company officials facilitated the team — they set goals, measured progress, and opened communication lines with the front line and official agencies.

Given the common goal to do what they could and coordinate, employees came up with some spontaneously creative solutions, including:

- Mobile pharmacies as well as free medications at their stores for evacuees without a prescription.

- Free check cashing for payroll and other checks.

- Clinics that offered inoculations against flood-borne illnesses.

Within two days, the company got tractor trailers full of supplies past roadblocks and into the city. They provided water and food to refugees a day before the government appeared on the scene. In total, Wal-Mart sent 2,498 trailer loads of supplies and donated $3.5 million in goods to shelters and command centers.

The lesson is that under extreme and complex conditions, where a single person has insufficient knowledge to make the right calls, if people are empowered to act, work together, and adapt, they can achieve extraordinary success where centralized control would fail.

Incorporating Empowerment into Checklists

The building industry consistently and successfully manages complexity with its two-pronged approach to checklists:

- A schedule/checklist to ensure that important things get done.

- A checklist to make sure people communicate, coordinate, and take responsibility, while being empowered to tackle small and large problems and uncertainties.

The building industry’s approach combined with the experience of Hurricane Katrina suggests that in complex situations, checklists are essential for success. But they also must allow room for judgment coupled with communication and responsibility.

Checklists Everywhere

As he explored the capabilities of checklists, author Gawande began finding them in use in unexpected places. Here are two examples:

1) Van Halen concerts: Many people have heard the story about rocker David Lee Roth’s insistence that Van Halen contracts with local concert promoters contain an unusual clause. It requires that a bowl of M&Ms be provided backstage, but with all of the brown candies removed or the show would be canceled. In at least one case, the band canceled a show for that reason.

Roth later explained in his memoir, Crazy from the Heat, that the clause actually was a test to see whether the promoter had read the details of the contract. Reading the “fine print” was important because the contract was, in effect, a checklist of steps that needed to be taken to set up the stage safely. If the directions weren’t followed exactly, people could be injured. Roth added the M&Ms clause when the group started performing in smaller regional venues where local crews might make technical errors with the set-up. It paid off because in Colorado the local promoter had failed to read weight requirements, and the equipment would have fallen through the arena floor.

2) Rialto restaurant, Boston: Jody Adams, chef and owner of the popular restaurant focusing on regional Italian cuisine, uses checklists to achieve excellence and consistency.

A recipe for each dish is placed in clear plastic sleeves at each station — line cooks need to consult them because recipes are revised at times. Also, there’s a checklist for every customer. When an order is placed at the front of the restaurant, it’s printed out in the kitchen, with customer details and preferences noted in a database from previous visits. The sous chef reads the orders aloud, and line cooks are expected to repeat the items to confirm they heard them correctly.

Adams also has a communication checklist to ensure that her staff recognizes and handles unexpected problems as a team. An hour before opening, she has a quick team meeting to discuss any unexpected issues or concerns — for example, a delay in a birthday party of 20 girls, which meant they’d arrive during the dinner rush. Whatever the issue, everyone gets a chance to speak and they plan how to handle it.

As a final check, Adams or her sous chef reviews every plate before it leaves the kitchen to make sure it looks good and matches the order. About 5 percent are sent back.

Even in a profession like cooking, which is more art than science, checklists are helpful.

Chapter 5: The WHO Checklist Project

In 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO) asked Gawande to organize a group to solve a problem: Surgery was increasing rapidly worldwide, but surgical patients were getting unsafe care so often that surgery was a public danger. WHO sought a global program that would reduce avoidable harm and deaths from surgery.

Data from 193 countries showed that the volume of surgery worldwide had skyrocketed by 2004. Surgeries exceeded totals for childbirth, but the death rate for surgery was ten to one hundred times higher than for childbirth. At least seven million people a year were disabled by surgery, and one million died.

The growth was due in part to improved economic conditions, which increased people’s longevity and therefore their need for surgeries. Health systems were greatly increasing the number of surgical procedures performed and the types of surgeries. There were more than 2,500 different surgical procedures. Safety and quality of care for surgical patients was becoming a big issue everywhere.

Surgery is often life-saving, even when performed under dire or substandard conditions. But failures leave millions disabled or dead. In the U.S. alone, when Gawande began the WHO project, at least half of surgical complications were preventable, and there were a variety of causes and contributing factors. He set out to find examples of public health interventions and campaigns that had succeeded. He found several examples, all of which shared three characteristics: they were simple, their effects were measurable, and the benefits could be applied elsewhere.

Simple, Measurable, and Applicable Solutions

A U.S. public health worker in Pakistan came up with a way to reduce deaths, infections, and diseases among children in poor areas of Pakistan, with a high level of illiteracy, overcrowding, open sewers, and contaminated water.

The health worker provided soap donated by Proctor & Gamble along with simple guidelines describing six situations in which people should use it and instructions on hand-washing techniques. The soap was a behavior-change vehicle. People appreciated getting the free soap, even though some already had their own own soap. They also liked its scent and a significant number followed the instructions, which were basically a checklist. The incidence of diarrhea among children fell 52 percent. The incidence of pneumonia fell 48 percent and bacterial skin infections fell 35 percent.

The successful soap project was simple, measurable, and widely applicable.

Columbus Children’s Hospital

In 2005, Columbus Children’s Hospital developed a checklist to reduce surgical infections, one of the most common complications of surgery in children. A key to avoiding infections is giving an antibiotic within sixty minutes before the surgeon makes an incision. However, this step was often missed — the hospital’s records showed that a third of pediatric appendectomy patients didn’t get the antibiotic at the right time.

So the hospital’s director of surgical administration designed a checklist, which was put on a whiteboard in each operating room. It included a step to confirm that antibiotics had been given. The director, who was also an airplane pilot, called the program “Cleared for Takeoff.” A key feature was a metal “tent” labeled with the slogan, which the nurse placed over the scalpel when she laid out the surgical instruments. The surgeon couldn’t start until the nurse gave the OK and removed the tent.

After three months of using the system, the surgical director found that 89 percent of appendicitis patients had received the antibiotic. After ten months, 100 percent did — the checks instilled a performance standard.

University of Toronto

The University of Toronto performed a feasibilty study using a 21-item surgical checklist designed to catch a range of potential errors in surgical care. It combined task checks with communication points.

The surgical staff had to verbally confirm each item on the list — for instance, that an antibiotic had been given, that the right type of blood was available, and that test results were on hand. The checklist also incorporated a team briefing to talk about any risks or concerns as well as expectations (for example, how much blood loss was expected and what things to be prepared for).

Researchers monitored use of the checklist in eighteen operations. In ten, it revealed significant problems or ambiguities, including individual patient problems that a checklist wouldn’t typically catch.

Kaiser Hospitals

A study at a group of Kaiser hospitals in southern California further underscored the importance of communication and a sense of teamwork in surgery. The hospitals tested a thirty-item “surgery preflight checklist.”

The checklist included preventive steps for surgery’s three biggest killers — infection, bleeding, and unsafe anesthesia. However, a fourth killer — the unexpected — can’t be dealt with as readily with check boxes. So the program addressed it by setting up communication checkpoints. The checklist required surgical staff to stop and talk through the case together in order to be ready as a team to identify and address each patient’s unique concerns and risks.

This was unusual because, typically, surgery is treated as a one-person show. The operating room is referred to as a theater and functions as the surgeon’s stage. Surgeons like to think that surgical staff perform as a team, but often they really don’t. For instance, not all team members are aware of a given patient’s risks, problems they need to be ready for, or even why the surgeon is doing the operation. One survey of 300 staff members leaving the OR showed that one in eight weren’t sure where the incision would be until the operation started. This one-person-show approach makes it more difficult for staff to come together effectively in a crisis.

Checklists requiring communication also address another problem with surgery — “silent disengagement.” This is the tendency of each person to focus on a specialized task, sticking to their own area of expertise while not questioning what anyone else is doing or paying attention to the big picture. To avoid failures in surgery, staff members need to see their job not just as performing specialized tasks, but also as helping the group get the best possible results. This requires working as a team to address problems that arise and to ensure nothing falls through the cracks.

Kaiser’s checklist insisted that people talk together, which fostered teamwork. It also required staff members to introduce themselves with their name and role, ensuring all team members knew each other’s names. Studies in various fields have shown that people who don’t know each other’s names don’t work as well together as those who do.

Further, research at Johns Hopkins showed that when nurses were given a chance at the beginning of a procedure to state their names and concerns, they were more likely to note problems during surgery and offer solutions. The researchers referred to this as the “activation phenomenon” because giving people a chance to speak early on activated a sense of responsibility and willingness to speak up.

Results

Kaiser hospitals tested the checklist for six months in 3,500 operations. It caught numerous near errors, including almost doing the wrong procedure in one case. In addition, the rating by surgical staff of the teamwork climate improved from good to outstanding. Employee satisfaction rose and OR nurse turnover dropped.

None of these studies were proof that a checklist could be devised that would be effective and versatile enough to improve surgery outcomes around the world, but they provided a starting point for further exploration. Gawande and his team began drafting a potential surgical checklist, but soon realized they needed more information on what makes an effective checklist.

Chapter 6: Creating an Effective Checklist

While it should be simple to use, developing an effective checklist isn’t a simple task. It requires analysis, real-world testing, and revision.

Daniel Boorman, flight desk designer for Boeing, is an expert at developing checklists. He’s analyzed thousands of crashes and mishaps in an effort to figure out how to create checklists that prevent human errors.

Boorman’s checklists for Boeing aircraft fill a thick spiral-bound handbook with tabs. Yet each checklist is brief, consisting of a few lines on a page in large, easy-to-read type. Each applies to a different situation; together they encompass a range of scenarios. At the beginning of the notebook are what pilots call “normal” checklists for routine operations — for instance, steps to take before starting the engines. They’re followed by “non-normal” checklists for emergency situations such as engine failure, smoke in the cockpit, or an insecure door.

Over two decades, Boorman has learned how to make checklists that work. There are key differences between bad and good checklists.

Bad checklists are:

- Unclear and imprecise.

- Too long, impractical, and difficult to use.

- Created by pencil pushers who lack experience doing what their checklists dictate.

- Overly detailed. They try to spell out every single step, as if the users are clueless.

- Mind-numbing, rather than engaging.

Good checklists:

- Are precise, efficient, concise, practical, and easy to use even in the most difficult circumstances.

- Don’t try to spell out everything. They provide reminders of only the most important steps that even an experienced professional could miss.

How to Create a Checklist

(Shortform note: also see the Appendix: A Checklist for Checklists.)

Before creating a checklist, decide two things:

1) Define a clear ‘“pause point” at which the checklist is to be used (unless the moment is obvious, such as when something malfunctions).

2) Decide whether to create a Do-Confirm list or a Read-Do list.

To use a Do-Confirm checklist, team members perform their jobs from memory. Then they stop and go through the checklist and confirm that they completed every item on the checklist. In contrast, to use a Read-Do checklist, people carry out each task as they check it off, like a recipe.

(Shortform note: Choose the type of checklist that makes the most sense for the situation. For instance, a Read-Do list could be used when the sequence needs to be exact or the entire effort will fail, like in operating machinery or listing emergency tasks. A Do-Confirm list gives more freedom and is allowable when the stakes are lower, and a forgotten step can be done later out of sequence.)

Once you’ve chosen which type of checklist you’re creating, follow these guidelines:

- Keep the checklist short, typically five to nine items, which is the limit of short-term memory. After 60 to 90 seconds, a checklist becomes a distraction from other things. People are likely to skip or miss steps.

- Focus on the “killer” items or steps that are most dangerous to miss but that are still sometimes overlooked.

- Remember that checklists are not supposed to be how-to guides. They are quick, simple tools to aid the recall of experts.

- Keep wording simple and exact.

- Use language and terminology familiar to the user.

- Fit the checklist on one page.

- Avoid clutter and unnecessary or distracting colors.

- Use upper and lowercase text in a sans serif font for ease of reading.

Test your checklist in the real world — have people use it and provide feedback. Boorman tests his checklists in a flight simulator. Language that you think is clear may not be to someone else. In practice, things are always more complicated than anticipated. Keep revisiting and testing the checklist until it works consistently.

Why Pilots Trust Checklists

Some of the most effective checklists come from the world of aviation. Pilots readily turn to checklists because they’re trained to do so, from the beginning of flight school. They know their memory and judgment are fallible, and that lives depend on their recognizing that fact.

They also know that checklists have proven their worth and don’t hesitate to turn to them in emergencies. For example, pilots turned to a checklist and saved lives in 1989 when a forward cargo door blew out on a flight from Honolulu to New Zealand, and flying debris damaged a wing and two engines. In under two seconds, nine passengers were sucked from the plane and lost at sea.

The pilots didn’t know what had happened — they thought a bomb had gone off — but they knew cabin pressure and oxygen had dropped. Voice recordings show that they immediately turned to a checklist. Following protocol, they reduced altitude, shut down the two damaged engines, tested the plane’s ability to land with wing damage, dumped fuel to lighten their load, and safely returned to Honolulu with 328 remaining passengers and 18 crew members.

As another example, in 2008, the engines gave out on a British Airways flight from China when it was only two miles from London Heathrow Airport. The pilots crash-landed the Boeing 777 at 124 miles per hour in a grassy field a quarter-mile short of the runway, but everyone survived.

The cause wasn’t provable, but investigators theorized that ice crystals had formed in the fuel lines as the plane flew over extremely cold regions. Boorman’s Boeing team created a checklist of new procedures for dealing with a fuel blockage caused by ice crystals, and within a month it was in the hands of pilots and in cockpit computers.

Later that same year, it was put into action, when a Delta flight from Shanghai to Atlanta had engine failure over Great Falls, Montana, due to ice in the fuel lines. Pilots followed their checklist, slowing instead of revving the engine to give it time to recover, and 247 people were saved.

A Lesson for Medicine

While Boorman and his team at Boeing quickly got new information into a useful form and out to the people who needed it, the field of medicine is notoriously slow to put new information into action.

A study following nine new treatment discoveries showed that on average it took doctors 17 years to adopt new treatments for at least half of American patients. When it comes to errors, medical professionals don’t typically conduct investigations the way aviation investigators do. And even if they do investigate a failure and learn something, they might issue voluminous guidelines unlikely to be read, make an addition to a textbook, or mention the new information in a seminar.

The knowledge basically doesn’t get out because it hasn’t been put into a simple, usable form and distributed systematically. The world of medicine is in need of effective checklists.

Chapter 7: WHO Tests a Checklist

With information from Boorman on how to create an effective checklist, Gawande and his team created and began testing a Surgical Safety Checklist for WHO.

They chose a Do-Confirm approach to give people greater flexibility in performing their tasks, but had them stop at key points to confirm they hadn’t missed any steps. When researchers tested the checklist in a simulated surgery, they realized they hadn’t designated who was supposed to pause things and launch the checklist. They decided to have the circulating nurse call the pause rather than the surgeon, to send the message that everyone is responsible for the overall well-being of the patient in surgery.

They had a team in London try the checklist, then one in Hong Kong, and continued to improve it. The final WHO checklist listed 19 checks with three pause points and it took two minutes to go through. The checks were divided as follows:

- Before anesthesia: seven steps, such as checking patient consent, medication allergies, and availability of replacement blood.

- After anesthesia and before making the incision: seven more checks, including making sure team members have been introduced by name and role and have discussed aspects of the operation.

- Before the patient leaves the OR: five checks, including an accounting of all surgical equipment and a review of plans for the patient’s recovery.

Next was a pilot study of the Safe Surgery Checklist in eight hospitals around the world.

The researchers chose a diversity of hospitals, rich and poor, because failures can happen anywhere.

To establish a baseline, they collected data on current complications and death rates at the test sites. Of 4,000 patients, 400 had developed major complications from surgery and 56 died.

About half the complications involved infection, and a quarter involved failures that required a return to the OR to fix something or stop bleeding. Complication rates ranged from 6 to 21 percent, which indicated room for improvement everywhere.

They began implementing the checklist in the pilot hospitals in spring 2008. To help get buy-in, they provided each hospital with its failure data to show what the list was trying to address. They presented the checklist as a tool for people to try in hopes of improving their results.

Use of the checklist was well underway within a month and they began hearing encouraging stories. For instance:

- In London, the before-incision part of checklist caught a wrong-size prosthetic knee about to be used as a replacement.

- In India, surgical staff discovered a flaw in their system: they were giving the antibiotic too soon. Frequent delays in the operating schedule meant it had worn off by the time surgery started, so they changed their system.

- In Seattle, they caught problems with antibiotics, equipment, and overlooked medical issues. They also found that going through the list helped the staff respond better if an unexpected problem came up — they worked better as a team.

Three-Month Results

The results after just three months exceeded researchers’ hopes and expectations:

- Rates of major complications for surgical patients in all eight hospitals fell by 36 percent. Deaths fell 47 percent.

- Infections fell by almost half.

- The number of patients having to return to the OR because of problems fell by a quarter.

Overall, in the group of nearly 4,000 patients, 435 would have been expected to develop serious complications based on the baseline observation data. Instead just 277 did. Using the checklist had spared more than 150 people from harm and 27 of them from death.

Every hospital in the study saw a substantial reduction in complications. Seven of the eight hospitals experienced a double-digit drop. Because of their significance, the results were published by the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2009 as a rapid-release article.

Results had already begun to leak out prior to publication, and hospitals in Washington state had begun using Seattle’s checklist. The hospitals formed a coalition with Boeing (a major employer), the state’s insurers, and the governor to introduce the checklist across the state and track data.

In Great Britain, the chairman of surgery at St. Mary’s Hospital, which was part of the study, became the country’s minister of health and helped launch a campaign to implement the checklist nationwide.

Some surgeons objected that the study had not clearly established how the checklist was producing the results (the decline in complications from surgery). For instance, while the hospitals made improvements in procedures such as giving antibiotics and making sure they were doing the right procedure, the improvements didn’t explain why unrelated complications, like bleeding, fell.

Researchers suggested the results were due to improved communication. In spot surveys, surgical staff reported a significant increase in the level of communication. There also was a correlation between teamwork scores and results for patients — the more that teamwork improved, the more patient complications declined.

After using the checklist for three months, more than 250 staff members filled out an anonymous survey. Among the results:

- 80 percent said the checklist was easy to use, didn’t take long, and improved care.

- 78 percent said they saw the checklist prevent an error.

- 93 percent agreed that if they were having an operation, they’d want the checklist to be used.

Chapter 8: Heroism in Medicine and Aviation

If someone discovered a new drug that reduced complications from surgery as much as the checklist did in the pilot study, it would be rushed to the market. Competitors would start making better versions. If the checklist were a medical device, every surgeon would want it.

Since the results of the WHO checklist were published in early 2009, more than a dozen countries pledged to implement checklists. By the end of 2009, about 10 percent of U.S. hospitals and 2,000 worldwide had implemented or pledged to implement the checklist.

However, since this early enthusiasm, it’s proven more difficult to persuade doctors to change their Lone Ranger culture to one of teamwork, starting with checklists. If they did, good checklists could become as important for them as stethoscopes (which, unlike checklists, have never been proven to improve patient care).

Tom Wolf’s book, The Right Stuff, chronicles the passing of the maverick test pilot culture.

Being a test pilot was extremely dangerous when the job began — pilots needed courage and an ability to improvise: the right stuff. But as knowledge and complexity of flying grew, and pilots began using checklists and flight simulators, the emphasis shifted from grandstanding to safety, effectiveness, and teamwork in high-risk, complicated situations.

A similar shift is occurring in medicine and other fields as complexity demands new approaches, including checklists. Checklists don’t replace the need for skill, boldness, and courage — they enhance these qualities by improving focus, making sure you have critical information when you need it, and minimizing human error. What’s needed in today’s complex world is an updated definition of heroism. Again, aviation offers a model.

Redefining Heroism

On Jan. 25, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549 left La Guardia Airport with 155 on board, hit a flock of geese, lost both engines, and crash-landed in the icy Hudson River. Investigators later called it the most successful ditching in aviation history. Pilot Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger III was hailed as a hero.

But Sullenberger repeatedly emphasized that it was a crew effort. Many factors contributed to the “miracle on the Hudson”: procedures and checklists, the fly-by-wire computer system that controlled the airplane’s glide to the water, the copilot, and the cabin crew who handled the evacuation. Success was as much a result of teamwork and adherence to procedure as it was of skill and coolness under pressure.

Here’s how events unfolded. Sullenberger and First Officer Jeffrey Skiles, equally experienced pilots, were flying together for the first time. To begin with, they ran through their checklists and introduced themselves to each other and the cabin crew. They held a briefing, discussing the flight plan, potential concerns, and how they’d handle problems. They created a team, ready for the unexpected, which occurred ninety seconds after takeoff when the plane collided with a flock of geese. Two engines were each hit by at least three geese and immediately lost power.

Sullenberger made two key decisions almost instinctively: to take over flying the airplane and to land in the Hudson River. He knew the plane had too little speed to make it back to La Guardia or to Teterboro Airport in New Jersey. He had more hours than Skiles in flying the A320, and the key landmarks to avoid hitting were visible from his left-side window.

Skiles had just completed A320 training and was more recently familiar with the checklists. While Sullenberger looked for a place to land, Skiles went through the engine failure checklists to try and restart the engines, while also preparing for ditching. First, he focused on restarting, since that offered the best chance of survival. He completed the restart sequence without success on both engines, a remarkable feat in the short time they had. Next, he began ditching procedures: he sent distress signals, notified the crew, and configured the plane for an emergency water landing.

Sullenberger focused on the descent to the water. The fly-by-wire control system kept the plane from drifting and wobbling, and it maintained an optimal angle for descent. It enabled the pilot to focus on other critical things, including finding a landing site near ferries and keeping the wings level as the plane struck the water.

The three flight attendants also followed protocols: they instructed passengers to put their heads down and brace for impact. After landing, they instructed everyone to put on life vests, got the doors open, and made sure passengers didn’t waste time gathering belongings. They got everyone out in three minutes, with only two of the three exits useable. Sullenberger checked the condition of the plane and passengers, while Skiles ran the evacuation checklist, for instance making sure fire hazards were dealt with. Ferries and boats arrived to pick up passengers, while air in the fuel tanks kept the plane afloat. Sullenberger walked the aisle to make sure no one had been forgotten, and only then finally left the plane.

Who was the hero? The 155 people on board were saved by something much bigger than individual heroism and skill. It was the crew’s ability to follow vital procedures in a crisis, stay calm, and recognize where to improvise and not improvise. They operated as a team under complex and dire circumstances, having prepared to do so before the crisis.

This is the definition of heroism in the modern era.

Adding Discipline as a Value

All professional occupations have a code of conduct with three expectations in common:

- Selflessness: You place the needs of others who depend on you above your own.

- Skill: You strive for excellence in knowledge and expertise.

- Trustworthiness: You act responsibly toward others.

Unlike most professions, aviation has a fourth expectation: discipline, in following procedures and working with others. In medicine, the fourth element is autonomy, which runs counter to discipline. However, in large enterprises involving complex, high-risk technologies, where the knowledge needed exceeds the capacity of any individual, what’s needed is discipline.

The aviation industry has made discipline a norm. They study failures and incorporate checklists, which they regularly revisit and refine. They employ procedures and teamwork to make the systems we depend on work.

Medicine, however, obsesses over having great components but pays little attention to making them work together. Medical professionals don’t study failures with the intent of improving solutions. They just work harder, dropping the same balls repeatedly. The only viable option, given the complexity of the world, is to learn from and emulate pilots.

Chapter 9: Saved by a Checklist

In 2007 as soon as the Safe Surgery Checklist took shape, Gawande began using it in his surgeries. Hardly a week went by without the checklist enabling the team to catch something they would have otherwise missed.

For instance, in one week, there were catches in five cases, including:

- A patient hadn’t gotten the antibiotic she should have.

- The surgeon learned of a breathing risk at the last minute.

- The team discovered drug allergies, equipment problems, confusion about medications, and labeling mistakes.

In another case, the checklist saved the patient’s life. Gawande was performing surgery to remove a man’s adrenal gland because of a tumor. He made a catastrophic tear, resulting in massive bleeding and cardiac arrest. But due to the checklist, four units of the right blood were available and ready to go — this step saved the patient’s life. In addition, staff members were prepared to work as a team and everyone stayed calm and did what was needed. Although he had a long recovery, the patient survived.

Appendix: A Checklist for Checklists

Creating a checklist involves three phases, each with key steps, including the following.

Development

Establish clear, concise objectives. Each task you include should be:

- A critical safety step that is easily missed.

- A step not covered by other means.

- Actionable, requiring a specific response.

- Designed to be read aloud.

Also, include items to improve communication among team members. Involve team members in creating the checklist.

Drafting

The checklist should:

- Use logical breaks in the workflow (pause points). There should be fewer than ten items per pause point.

- Use simple sentences and language.

- Have a title reflecting its objectives.

- Have a simple, uncluttered, and logical format.

- Fit on one page.

- Minimize the use of color.

- List the date of creation or latest revision.

The text should be:

- Sans serif.

- Upper and lower case.

- Large enough to be read easily.

- Dark on a light background.

Finalizing

- Test the checklist with front-line users (in either a real or simulated situation).

- Revise it in response to repeated trial runs.

- Make sure it fits the workflow.

- Ensure the checklist can be run in a relatively short amount of time.

- Plan for regular review and revision.

Exercise: Applying a Checklist

Checklists help to prevent mistakes because: 1) our memory and attention to detail tend to fail when we’re distracted by more urgent matters and 2) we have a tendency to skip steps even when we remember them. Consider how you might use checklists in your everyday life.

Think of an important task you do regularly, such as changing the oil or doing other vehicle maintenance, that requires multiple steps. Think of a time when you forgot or skipped a step. What was the result?

How would a checklist help this process go more smoothly?

How could you find and incorporate a checklist — for instance, by creating a laminated list and/or having someone read the tasks as you do them?

Exercise: Checklists at Work

Checklists are widely used in the construction and aviation industries. Also, the book describes uses in medicine, finance, and in the restaurant industry. The author argues they’re applicable in virtually any field, but are underutilized. Consider how you might use checklists to improve your effectiveness at work.

Do you or anyone else at work use checklists in your occupation to improve outcomes for customers? If not, what are some ways they could be incorporated? What would the benefits be?

If checklists are used, how could they be improved or used more effectively?

What obstacles do you see to using or improving checklists at work? How could they be overcome?

Exercise: Make a Checklist

Checklists should be short, clear, and contain the “killer” steps (the ones with the greatest consequences if you miss them) as well as routine steps you might miss. Create a checklist to increase the effectiveness of your routines at work or at home.

Think of a task that you or others perform at home or at work that is error-prone (if you like, you can use the example you chose for one of the previous exercises). Describe what a checklist for this task would look like — define the task, determine the pause points or logical breaks in the workflow, and the steps to be taken after each pause.

Draft the checklist, and have someone else walk through it. How did it work? What improvements were needed?

How can you implement the checklist? If you need buy-in from others, how can you get it?