1-Page Summary

Investing well over the long term does not require incredible intelligence or deep insight. Instead, it requires two things:

- A rational framework for making decisions

- Preventing your emotions, and other people’s emotions, from overriding your framework

With these two elements, and without extensive trading experience, you can do better than more financially-educated people who lack patience, discipline, and emotional control.

Investing successfully in stocks requires keeping a few key principles in mind:

- A stock is not just a mere object you trade. It is a piece of ownership in a business. Therefore, the stock has a fundamental value that is often not the share price. Understand the business, and you understand the fundamental value.

- Pay attention to the price at which you buy stock. The more you pay for a stock, the lower your return will be. Buying stock carelessly, with the expectation that you can buy anytime at any price and still profit, is a mistake. As Graham says, “buy your stocks like you buy your groceries, not like you buy your perfume.”

- The market has constant mood swings. At times, it is over-optimistic, which makes stocks too expensive. At other times, it is pessimistic, which makes stocks cheap. The key is to buy from pessimists and sell to optimists.

- Keep a “margin of safety”—don’t get carried away and overpay for a stock, or a downturn can cause irrevocable losses.

This book covers two major types of intelligent investors—defensive investors and aggressive investors—and advises how each should invest. It also covers general investment principles and market behavior, popularizing Graham’s famous concepts of Mr. Market and Margin of Safety.

Let’s begin by discussing what investment is.

Investors vs. Speculators

What are investors? The term is thrown about loosely to describe anyone who buys or sells securities in the market. But since many people trade irresponsibly and by their emotions, describing them as “investors” seems too generous. For instance, if the stock market suffers a major drop, the media will report, “investors became bearish and pulled out of the market.” Yet these moments are precisely when sound investors would be buying stocks on the cheap.

Offering a more robust definition, Graham defines investment as an operation that, through extensive analysis, provides an adequate return and safety of principal. Everything that doesn’t fit this definition is speculation.

Investors and speculators therefore behave very differently.

Speculators trade on market movements of stock price They buy stocks as they move up, hoping to sell to someone who will pay more for it. When the price goes down, they sell to capture their gains or cap their losses. In all this, they ignore the fundamental value of what the company is worth.

Investors look at the fundamental value of the stock, independent of the stock price. In fact, Graham suggests that investors should be comfortable buying stock even if they could receive zero future information about its daily stock price. Investors also trade oppositely to speculators—they buy when the market is down, since stocks are cheap. Investors dread bull markets since it makes everything overpriced.

Speculators are swayed by popular opinion. They hear optimistic estimates from analysts and buy stock, without questioning the underlying value. They buy when everyone else is buying, and sell when everyone else is selling.

Investors are independent thinkers. They use a dependable system for decision-making.

Don’t Believe the Active Trading Hype

You’ve likely seen commercials for stock brokerages that let you trade more conveniently and with lower fees than ever before. Beware: brokerages make money when you trade, and not when you make money. Therefore, brokerages hype up speculation for common investors in their marketing, promising riches at unprecedented speed.

In reality, active trading worsens your performance. A 2000 study by finance professors found that the most active traders (who turned over more than 20% of their holdings each month) underperformed the market by 6.4% per year, while the least active traders (trading less than 0.2% of holdings each month) matched the market.

Defensive vs. Aggressive Investors

Having distinguished investors from speculators, Graham defines two different types of intelligent investors: defensive investors and aggressive (or enterprising) investors.

Defensive investors want to avoid spending too much time on investing. They like simplicity and don’t love thinking about investments or money. Their goal is to perform on average, in line with the market, and to avoid serious mistakes.

Aggressive investors are willing to devote serious time and energy to research stocks and select good ones. They enjoy thinking about money and see smart investing as a competitive game they want to win. Their goal is to achieve better returns than the passive investor (Graham says an extra 5% per year, before taxes, is necessary to justify all the effort.)

Both approaches can be intelligent and can perform well. The key is choosing the right type of investment for your temperament and goals, to stick with it over your entire investment timeline, and to keep your emotions well under control.

The Defensive Investor

How Should Defensive Investors Invest?

Graham’s recommendation is to split investments between stocks and bonds. The default split is 50-50 between stocks and bonds. This allows you to participate in both the gains of stocks as well as the relative safety of bonds.

At times, you can shift your balance in favor of stocks or bonds. If you feel stocks are overpriced and due for a downturn, you can shift your investment to 25% in stocks and 75% in bonds. Likewise, after a steep market downturn or when stocks are cheap, you might shift to 75% in stocks and 25% in bonds. But Graham advises no more than a 75-25 imbalance.

Why not 100% into either bonds or stocks?

- Stocks on average rise faster than inflation, whereas bonds might not, so holding stocks better protects against inflation.

- However, stocks don’t always outperform bonds at all times. At the time of Graham’s last revision in 1973, bonds were outperforming stocks. Keeping a balance helps you weather a variety of economic conditions.

- Stocks fluctuate much more than bonds do, and the wild oscillations of a 100% stock portfolio will test your psychology.

Dollar-Cost Averaging

If you have a lump sum of money, how would you invest it? Some investors, tempted to get higher than market returns, might choose to “time the market,” waiting until a market dip to invest. The very likely risk is that the investor turns out to be entirely wrong, either losing out on gains as the market rises, or mistiming the bottom.

In contrast, Graham recommends dollar-cost averaging—split up the lump sum into multiple investments of equal amounts, distributed over a longer period of time (such as every month or quarter). This is a straightforward strategy that requires minimum thinking and emotional investment.

Dollar-cost averaging carries psychological benefits: you remain emotionally detached from the swings of the market. Regardless of whether prices are up or down, you invest the same amount.

It also helps you avoid the delusion that you can predict the market. Zweig notes that your response to any question about the market should be “I don’t know and I don’t care.”

Low-Cost Index Funds are the Default Option

In the book, Graham spends a few chapters giving advice on choosing specific individual bonds and stocks because, in the mid-20th century, those were the only options available to investors.

Since then, a large number of low-cost index funds have become popular (such as those by Vanguard). These funds hold a wide basket of assets, such as stocks and bonds, thus providing diversification with minimal effort. Near the end of his life, Graham noted that index funds should be the default choice of most everyday investors, rather than picking individual stocks (his protege Warren Buffett agrees).

Choosing Individual Stocks

If you do want to choose your own stocks, as a defensive investor you should buy only stocks of high-quality companies at reasonable prices. Use these seven criteria to filter the options:

- Size: More than $100 million in revenue

- Small companies face more volatility and may be unable to survive bad events.

- Graham’s criterion was set in 1970, and $100 million in revenue may be too small today. Nowadays, sufficient size might mean a market value of at least $2 billion.

- Strong financials: Assets at least double liabilities, and working capital more than long-term debt

- Dividends: Paid continuously over the last 20 years, without interruption

- Earnings: Positive in each of the past 10 years; no unprofitable years

- Earnings growth: At least 33% total growth in per-share earnings in the past 10 years (a bit less than 3% annually)

- A company that is shrinking over time will not be a good long-term investment.

- Use 3-year average earnings at both the beginning and end of the 10-year period.

- Price-to-earnings ratio: No more than 15 times the average past 3-year earnings

- Beware of analysts who calculate a “forward P/E ratio” using not historical earnings but “next-year’s earnings.” Predictions are notoriously unreliable, and often the forward P/E ratio is used merely to justify an overpriced stock.

- Price-to-book value ratio: No more than 150% of book value (also known as net asset value; calculated by subtracting total liabilities from total assets)

- In his commentary, Zweig notes that many companies today have a greater amount of value in intangible assets such as brand value and intellectual property, which don’t show up in book value. Thus, more companies are priced at higher price-to-book ratios.

These seven criteria are stringent and often cut away the majority of stocks. This is deliberate—at any time, most stocks are likely not good choices for the defensive investor.

The Aggressive Investor

In contrast to defensive investors, who want to minimize time and get acceptable results, aggressive investors want to devote serious time to investment research to achieve better returns than average.

When describing these investors as “aggressive,” Graham is not urging any carelessness or impulsiveness, despite general connotations of the term “aggressive.” In stark contrast, aggressive investors should methodically value potential investments, be patient for bargains, and maintain level-headedness when the market is reactive in either direction.

Expectations for the Aggressive Investor

How much in gains should a successful aggressive investor expect? An additional 5% per year, before taxes, is necessary to be worth the effort of all the research and work. (Graham notes repeatedly that good investors should not aim for stratospheric results, but rather modest and consistent returns over the long term.)

Beating the market is difficult, and Graham cautions—most professional money managers do not beat the overall market in the long term, after deducting fees. These funds employ highly intelligent and motivated people who dedicate their entire working days to researching and choosing individual securities. If they can’t outperform the S&P 500, do you think you realistically can?

Find Bargain Stocks

Graham’s core strategy is to find companies that are priced lower than their fair value. In other words, try to buy a dollar for far less than a dollar.

Why would this continue to work, despite the claims of the efficient market hypothesis? Because of human psychology. Markets are made up of people who are impulsive and follow each other. This can cause major fluctuations in price (both up and down) that are irrational relative to the stock’s underlying value.

When a company has fallen out of favor, its price will drop below what the fundamentals of the company would warrant. The stock has now become a bargain—if you buy them, they may later recover their prices and be good investments. Graham defines a bargain as a stock with a price that is below two-thirds of its value.

Bargains may occur when a large company endures a temporary setback, or when an entire industry falls out of favor. The market may overreact, moving certain stock prices into bargain territory.

Aggressive Investor Criteria

Like the defensive investor, start with statistical criteria for filtering all the stocks available. However, you can relax the criteria to include more companies:

- Size: No requirement for size. You can limit your risk with small companies by carefully identifying good companies and diversifying.

- Financials: Assets at least 1.5 times liabilities, and debt less than 110% of net current assets

- Dividends: Some dividends paid recently

- Earnings: Last 12 months’ earnings is positive

- Earnings growth: Last 12 months earnings’ more than earnings from 4 years ago.

- Price-to-earnings ratio: No more than 9 times earnings from the last 12 months

- Price-to-book value ratio: No more than 120% of book value.

To decide whether a stock is a good investment, you must do your own reasoned analysis. There is no such thing as good stocks and bad stocks—only cheap stocks and overpriced stocks.

- A strong company is not a good investment if its stock is overpriced.

- A stock at a low price is not a good investment if the company has poor future prospects.

- A stock with tremendous hype around growth, and high prices to match, is likely too speculative for intelligent investors.

- Yet a once-hyped stock that falls dramatically in value can then turn into a bargain stock worth buying.

Market Fluctuations and Mr. Market

When asked to predict what the market would do, the financier J.P. Morgan said, “it will fluctuate.”

You can be sure that the market will fluctuate. In all likelihood, you will not be able to predict when and how the market fluctuates. You can, however, respond to fluctuations in two critical ways:

- Steel yourself mentally for the fluctuations. Prepare for the idea that your portfolio may decline by 30% from its high point, and don’t tie your emotions to these fluctuations.

- Watch patiently and prepare to spot opportunities when they do appear. When the market sours on a stock, it can be an overreaction and present a bargain buying opportunity.

Mr. Market

You are not obligated to trade and sell with the market. You should use market pricing merely as an indicator for whether a stock is over- or under-priced, taking advantage of opportunities in your favor.

This sounds like common sense, yet countless traders behave as the market demands they do. They buy when stocks are going up and sell when they have gone down.

To illustrate how silly this is, Graham introduces his famous idea of Mr. Market. Say you own a piece of a business worth $1,000. Imagine a fellow named Mr. Market who is a manic-depressive sort of person and visits you once a day, asking to buy and sell your interest.

- When the market is up, he asks to sell another piece to you at exorbitant prices: $1,500, $2,000.

- When the market is down, he comes by asking to buy your stake for a steeply discounted $600.

Should you go along with this odd person, feeling exactly what he feels at every moment and doing what he demands?

Of course not. You know the piece of business is worth $1,000. You’d maintain your own rationality and politely ask this oddly behaving person to leave your house.

Mr. Market represents the whims and folly of other traders. His behavior should not influence yours. If you know the fundamental value of a business, why should the mistakes of other people influence your behavior? Behaving this way is like having your emotions and behavior dictated by other people.

You have no obligation to act according to market fluctuations. You should deliberately choose to transact only when it is in your favor. You shouldn’t ignore Mr. Market entirely, nor should you blindly follow whatever he tells you, but rather use his prices only when it is to your advantage. You are not obligated to trade with him.

Margin of Safety

In seeking good investments, Graham always made sure to build in enough margin of safety. In simple terms, margin of safety is a measure of how much can go wrong before an investment goes bad. If you make investments with a larger margin of safety, you have a greater likelihood of prevailing in the end.

Warren Buffett offers an analogy: If you’re designing a bridge that tends to support 10,000 pounds in everyday traffic, you should design it to carry 30,000 pounds.

Many of Graham’s investment criteria we’ve covered have margin of safety built into them:

- Interest coverage ratio: If a company’s earnings covers 5 times its interest expenses, then even if it suffers a sudden 20% drop in earnings, it has more than enough earnings remaining to continue paying interest and thus avoiding defaulting on debt. In contrast, a company that can only cover 1 times its interest expense is in danger of defaulting with just small setbacks to earnings.

- Price to book value: If you buy stock in a company when its market value is two-thirds of book value, the company’s book value can shrink by one-third before your investment becomes negative (relative to book value).

- Asset to liabilities ratio: If a company has assets at multiple times its liabilities, it can lose significant value before its bondholders suffer a loss.

A larger margin of safety prevents you from needing to be clairvoyant or unusually clever. You may not be able to predict market downturns or company setbacks, but with a large margin of safety, that doesn’t matter—your investment can still be successful.

As Warren Buffett has said about value investing, “if a business is worth a dollar and I can buy it for 40 cents, something good may happen to me.”

Introduction

Investing well over the long term does not require incredible intelligence or deep insight. Instead, it requires two things:

- A rational framework for making decisions

- Preventing your emotions, and other people’s emotions, from overriding your framework

With these two elements, and without extensive trading experience, you can do better than more financially-educated people who lack patience, discipline, and emotional control.

Investing successfully in stocks requires keeping a few key principles in mind:

- A stock is not just a mere object you trade. It is a piece of ownership in a business. Therefore, the stock has a fundamental value that is often not the share price. Understand the business, and you understand the fundamental value.

- Pay attention to the price at which you buy stock. The more you pay for a stock, the lower your return will be. Buying stock carelessly, with the expectation that you can buy anytime at any price and still profit, is a mistake. As Graham says, “buy your stocks like you buy your groceries, not like you buy your perfume.”

- The market has constant mood swings. At times, it is over-optimistic, which makes stocks too expensive. At other times, it is pessimistic, which makes stocks cheap. The key is to buy from pessimists and sell to optimists.

- Keep a “margin of safety”—don’t get carried away and overpay for a stock, or a downturn can cause irrevocable losses.

Warren Buffet read this book when he was 19 years old, and he still calls this “by far the best book about investing ever written.

Brief Biography of Benjamin Graham

Graham was born in 1894 and lived his childhood in New York. His father died when he was 9, the family business failed, and the family became poor. Her mother traded stocks on margin and became bankrupt in the stock market panic of 1907. This incident deeply influenced Graham’s thinking on the importance of not suffering grave losses in investing.

Graham attended Columbia for college and entered Wall Street. Here he obsessed over analyzing stocks and companies in minute detail. He eventually founded his investment firm, the Graham-Newman Partnership, where he employed a young Warren Buffett. Over 20 years, his firm returned 14.7% annually (after fees), compared to 12.2% for the stock market.

In 1956, Graham Graham retired and closed his partnership and continued teaching and writing, sharing his principles of value investing worldwide. He died in 1976, a few years after his last revision of this book.

Graham led the movement of “value investing” and deeply influenced some of the world’s most successful investors, most notably Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway.

Shortform Introduction

This book was first published in 1949, but it’s gone through multiple revisions since then. We’re summarizing the latest edition, which was published in 2003. Each of the 20 chapters in the book has two parts: 1) the original by Ben Graham, from his last revision in 1973, and 2) modern commentary by Jason Zweig, a finance columnist for the Wall Street Journal.

In his section, Graham often discusses the contemporary market of 1973, giving advice to the 1970s reader on how to invest based on the market conditions then. We’ll largely skim over these details to focus on the timeless principles, but we’ll keep the best examples.

Zweig’s modern commentary points out how Graham’s advice has been timeless through major stock market events, such as Black Monday in 1987 and the dot-com bubble in 2000. Since the book was written in 2003, it doesn’t address the great financial crisis of 2008 or the decade-long bull market following that, but disciples of Graham’s value investing would have little doubt the principles still hold.

Throughout the summary, by default the ideas come from Graham’s writing; we note which ideas and updates come from Zweig. Any mention of history after 1973 should be assumed to come from Zweig.

The book is written for investors in the United States investing in United States securities, but the ideas are likely applicable to any modern financial market.

Chapter 1: What Is Investment?

Let’s begin by defining who investors are, in the context of this book.

Investors vs. Speculators

What are investors? The term is thrown about loosely to describe anyone who buys or sells securities in the market. But since many people trade irresponsibly and by their emotions, describing them as “investors” seems too generous. For instance, if the stock market suffers a major drop, the media will report, “investors became bearish and pulled out of the market.” Yet these moments are precisely when sound investors would be buying stocks on the cheap.

Likewise, people describe “speculation” loosely. Yet after a stock market crash, when sentiment is poor and all stocks are considered too risky, they’re often the most attractive for investment.

Offering a more robust definition, Graham defines investment as an operation that, through extensive analysis, provides an adequate return and safety of principal. Everything that doesn’t fit this definition is speculation.

Investors and speculators therefore behave very differently.

Speculators trade on market movements of stock price They buy stocks as they move up, hoping to sell to someone who will pay more for it. When the price goes down, they sell to capture their gains or cap their losses. In all this, they ignore the fundamental value of the stock. (Shortform note: This style of trading is common in day trading, chart reading, and “technical analysis.”)

Investors look at the fundamental value of the stock, independent of the stock price. In fact, Graham suggests that investors should be comfortable buying stock even if they could receive zero future information about its daily stock price. Investors also trade oppositely to speculators—they buy when the market is down, since stocks are cheap. Investors dread bull markets since it makes everything overpriced.

Speculators are swayed by popular opinion. They hear optimistic estimates from analysts and buy stock, without questioning the underlying value. They buy when everyone else is buying, and sell when everyone else is selling.

Investors are independent thinkers. They use a dependable system for decision-making.

Speculators have erratic mood swings, and are impatient. Their feelings govern their behavior, and they don’t act by any methodical, reliable system.

Investors control their psychology through ups and downs. They rely on their dependable framework for decision-making and don’t act impulsively.

Speculation Disguised as Investment

In addition to trading based on market movements, Graham cautions against these common methods of speculation that masquerade as investment:

- Trading based on short-term earnings reports: estimating future earnings accurately is already difficult in itself. But studying earnings is so common and competitive, with legions of analysts on Wall Street, that even if you get it right, the stock price probably already reflects those earnings.

- Trading based on long-term growth prospects: here you may have a more optimistic view of certain companies than the overall market. But Graham is once again skeptical that an individual investor has the insight and vision needed to consistently outperform the market on these predictions.

In his commentary, Zweig shares examples of popular formulas that failed to perform:

- The “January effect”: A strategy published in the 1980s that claimed that small stocks dip at the end of the year and rise at the beginning of the year. The explanation is that investors sell their worst stocks by the end of the year to reduce taxes; investment firms also sell falling stocks by year-end to make their annual performance look better. The January effect looked strong up until the 1980s, after which it began disappearing.

- In 1996, a money manager named James O’Shaughnessy published a simple strategy in his book What Works on Wall Street: Buy 50 stocks with the highest one-year returns, 5 years of rising earnings, and share prices less than 1.5x revenues. He created funds based around this strategy, but they underperformed the S&P 500 through 2000, and some of those funds promptly shut down.

- The Motley Fool’s “Foolish Four”: Take the five stocks in the Dow Jones with the lowest price and highest dividend yields; discard the one with the lowest price; invest 40% in the stock with the second-lowest price, and put 20% in the other three. Repeat each year. When published, the technique claimed to produce a 10.1% annual return above market in a back-test over 25 years. But when applied going forward, this failed to perform any better than random stock picking.

The takeaways:

- Strategies that seem to work when back-tested against historical data may be illusory. If you look for enough patterns, you will find some that seem to work, by mere chance, but they will fail to deliver consistent performance over time.

- Even if the strategy really does work, if it becomes popular, the competitive market will adopt the strategy, thus erasing its possibility for profit. We’ll discuss this more in the last section of the chapter.

- Any simplistic strategy that mechanically picks stocks, without thorough consideration of the company’s underlying value, does not qualify as investment under Graham’s definition.

Speculation isn’t immoral or necessarily bad for society. Speculation based on the promise of future growth fuels innovation—new upstarts like Google or Amazon needed optimistic speculators to provide capital. But for most people, speculation is a poor way to attain wealth.

Don’t Believe the Active Trading Hype

You’ve likely seen commercials for stock brokerages that let you trade more conveniently and with lower fees than ever before. Beware: brokerages make money when you trade, and not when you make money. Therefore, brokerages hype up speculation for common investors in their marketing, promising riches at unprecedented speed.

(Shortform note: With the advent of mobile apps for trading and zero-commission trading, the barrier to trading is lower than ever. How do brokerages with zero commissions make money through trading? By selling order flow to market makers, who profit from inexperienced investors.)

As a result of these tools, trading activity has increased dramatically, as well as impatience—in 1973, a shareholder kept a stock for 5 years before selling it; by 2002, that shrunk over 80%, to 11 months. During frenzied periods, like the dotcom bubble in 1999, a share might be held an average of a few days.

Beyond just making poor investment decisions, active trading has other punishing drawbacks:

- A frenetic speculator who is desperate to buy or sell a stock may accept unfavorable prices for the sake of speed. For instance, someone who wants to trade 1,000 shares of a stock and misprices by 20 cents per share gives up $200.

- If you hold a stock for less than a year, any gains on that stock are taxed at ordinary income rates, rather than the lower long-term capital gains rate.

- (Shortform note: Recent research suggests that individual active traders even tend to earn below-market returns before accounting for fees—individual investors simply trade stocks poorly.)

Thus, accounting for small losses and taxes, an active trader might need to gain at least 5% just to break even.

A 2000 study by finance professors found that the most active traders (who turned over more than 20% of their holdings each month) underperformed the market by 6.4% per year, while the least active traders (trading less than 0.2% of holdings each month) matched the market.

The message is clear: “active trading is hazardous to your wealth.”

Shortform Exclusive: Why Do Individual Investors Do Worse?

There is ample evidence that individual investors do worse than the market. Why is this? Here are reasons borne out by research:

- Overconfidence: In general throughout much of life, people are overconfident about how much they know and how accurate they are. People who rate themselves as smarter than average trade more actively. Men tend to be more overconfident than women, and they trade more and perform worse than women do.

- Sensation seeking: Trading stocks is entertaining and provides emotional, visceral engagement the same way gambling does. In this way, trading can be seen to compete with other entertaining activities; when alternatives such as legal gambling and lotteries are introduced, active trading drops.

- Familiarity: Traders tend to over-invest in companies close to where they live or in the industry or company in which they’re employed. This leads to under-diversification and can have grave consequences when the employer goes bankrupt, as in Enron and Kmart.

- Disposition effect: Individual traders strongly prefer to sell stocks that have risen in value, and hold stocks that have fallen in value. In other words, they sell winners and hold losers. This is largely the opposite of what is prudent—the stocks that rise tend to rise even further, and likewise for falling stocks. (In turn, the reason traders do this can do with loss aversion, narrow accounting, and self-control issues. For more on these topics, see our summary of Thinking, Fast and Slow.)

If investors knew this, they would rationally invest in an index fund and stop trading. Still, many are attracted by the siren song and continue suffering poor returns.

Warnings for Speculators

At its most irresponsible, speculation should be seen as gambling. It can be entertaining and instructional, but it should never be confused for investing. Here are warnings for speculators:

- Don’t confuse your actions as investing when you’re really speculating. If your actions don’t require extensive analysis, don’t provide an adequate return over time, or don’t provide safety of principal, you’re speculating.

- Don’t be deluded by a speculative method that works in the short term. Good investing frameworks sustain over the long term. Day trading, chart analysis, and stock-picking systems may work for a short period, but they fail in the long run.

- Don’t speculate without knowledge or skill. Be humble about understanding your experience and track record. Study the results of other people with similar experience and skill.

- Don’t speculate with more money than you can afford to completely lose. If you really want to speculate, set aside some money for a speculation account (say, a max of 10% of your assets), and never add money to it.

Defensive vs. Aggressive Investors

Having distinguished investors from speculators, Graham then defines two different types of intelligent investors: defensive investors and aggressive (or enterprising) investors.

Defensive investors want to avoid spending too much time on investing. They like simplicity and don’t love thinking about investments or money. Their goal is to perform on average in line with the market, and to avoid serious mistakes.

Aggressive investors are willing to devote serious time and energy to research stocks and select good ones. They enjoy thinking about money and see smart investing as a competitive game they want to win. Their goal is to achieve better returns than the passive investor (Graham says an extra 5% per year, before taxes, is necessary to justify all the effort.)

Both approaches can be intelligent and can perform well. The key is choosing the right type of investment for your temperament and goals, to stick with it over your entire investment timeline, and to keep your emotions well under control.

In later chapters, we’ll dive much deeper into both defensive and aggressive investment strategies.

Exercise: What Kind of Investor Are You?

Define what kind of investor you should be.

Are you currently an investor or a speculator? Remember that investment is an “operation that, through extensive analysis, provides an adequate return and safety of principal.” investors always consider the underlying value of what they’re buying.

Have you ever speculated before? What did you do, and what was the result?

Going forward, how much time are you willing to spend on investment?

What are your expectations of returns, relative to the market average?

What kind of investor should you be? Why would you not want to be the other kind of investor?

Chapter 2: Inflation

Inflation is an increase in prices over time. A dollar today buys a lot less than a dollar did 20 years ago: the purchasing power of a dollar has decreased.

Inflation is an insidious problem, because it doesn’t change the actual balance of your bank account, it only changes the purchasing power of how much money you have. If 2% of your bank balance were deducted per year, you’d take notice and be alarmed. But when the same amount of money can buy 2% less in goods and services each year, it’s nearly undetectable.

Therefore, if you were to hold all of your savings simply in cash, it would gradually lose value because of inflation. In contrast, holding stocks in your portfolio reduces the effect of inflation. Even if inflation occurs in a given period, increases in the stock’s dividends and price may offset inflation. Bonds, being loans with fixed terms, don’t have the same flexible resistance to inflation.

We’ll discuss inflation in more detail and why stocks protect against it.

Measuring Inflation

How bad can inflation get? During certain periods, inflation can be rapid:

- In the US, in the 6 years from 1915 to 1920, cost of living nearly doubled.

- Also in the US, in the 10 years from 1973 to 1982, cost of living more than doubled.

- Zweig notes that since 1960, two-thirds of market economies have experienced inflation of at least 25% per year for at least a year. The US hasn’t yet experienced this, but it’d be unwise to assume it could never happen.

Averaging across much of the 20th century, Graham predicts that a reasonable assumption around inflation is 3% per year. (Shortform note: Since the start of the 21st century, inflation has stayed at a relatively steady 2% per year.)

Inflation and Stocks

How do stocks and businesses perform during inflation? There’s a lot of variability and plenty of exceptions to any rule, but, in his commentary looking back over the 20th century, Zweig notes in general:

- In periods of steady mild inflation, stock returns outperformed inflation.

- In periods of high (above 6%) inflation, stocks performed poorly. This might be because high inflation disrupts the economy—consumers purchase less, and businesses suffer.

Why Do Stocks Resist Inflation?

(Shortform note: This is a technical section we’ve included to be comprehensive; it’s not too relevant for the typical defensive investor.)

One theory of why stocks resist inflation is that during a time of inflation, a business’s costs increase, but it can also increase its prices at the same time, thus preserving its profits. In theory, a business can grow its revenues and profits at the same rate as inflation, and its stock price rises with inflation as well. In other words, a business can pass on the costs of inflation to its customers.

Graham analyzes these claims and finds that they fall short. Looking back on the 20th century, he agrees that stock prices have risen faster than inflation, but not because inflation had a direct effect on company financials. If the theory above were true, then companies would show higher earnings on capital during inflation (because the earnings should rise with inflation while the old capital investment stays the same). But this hasn’t appeared—earnings on capital have not kept pace with consumer prices.

Instead, much of the gain in earnings and stock price from 1950 to 1970 was due to two factors:

- Reinvestment of profits into the business

- Increasing corporate debt, used to grow the company faster

Protecting Against Inflation

Other than stocks, these two asset classes can also help protect against inflation:

- Real estate: Prices of real estate tend to rise with inflation. However, Graham warns that real estate prices can be volatile, and you can easily make mistakes buying the wrong property for the wrong price. In his commentary, Zweig recommends Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), which are tradable securities that hold a diversified basket of real estate properties.

- Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS): Introduced in 1997, TIPS are inflation-indexed bonds, meaning the value adjusts to inflation. You can buy them from the US government or from a fund as offered by Vanguard. Oddly, increases in TIPS principal value are taxed as income, so consider buying TIPS in a tax-deferred retirement account like an IRA or 401(k).

Other assets are commonly considered to protect against inflation, but Graham is skeptical:

- Gold: Gold’s supply doesn’t change much over time, as opposed to central banks creating more paper money, so it’s theoretically less subject to inflation. However, the price of gold has historically had a poor correlation with inflation, since gold prices fluctuate based on other factors.

- Exotic assets, like art or diamonds. Graham says he’s out of his depth here, and most readers likely are too.

Chapter 3: Is It a Good Time to Buy Stocks?

Is it a good time to buy stocks? This is a perennially difficult question to answer. Investment professionals, whose job is to figure this out, constantly get it wrong.

Public sentiment is even less reliable—when a large crash occurs, most people, having incurred large losses, declare stocks too risky; in reality, this is the time of greatest opportunity to buy. Conversely, when people expect growth to continue perpetually, they’re willing to buy at any price; this ebullience is inviting a steep crash to more reasonable levels.

In each edition of The Intelligent Investor, revised roughly every 5 years from 1949 to 1973, Graham gave an assessment of whether stocks were undervalued or overvalued, and thus whether investors should choose to invest or sit on the sidelines. In this chapter, he reflects on those predictions and the general method of evaluating the stock market. (Shortform note: For today’s readers, this is of course less relevant for its actual predictions and more to illustrate Graham’s thinking.)

Stock Market History

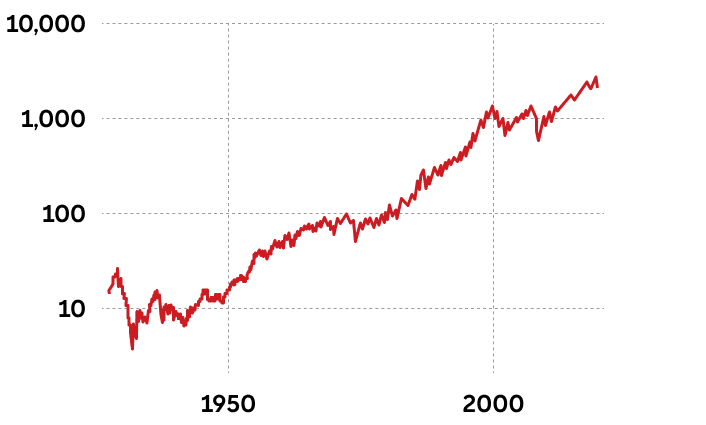

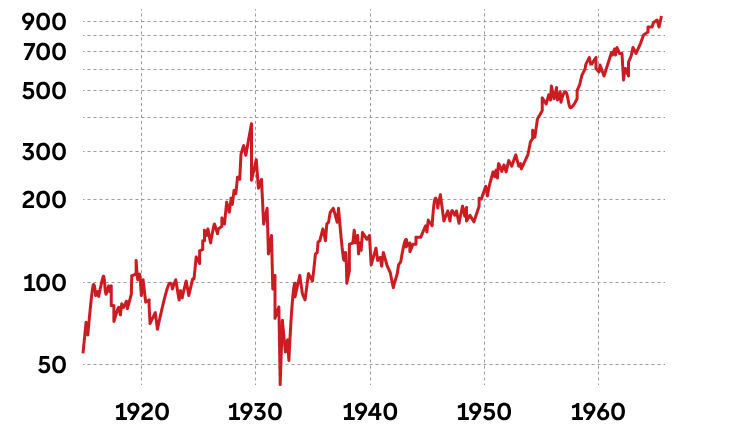

In hindsight, over the past 75 years, stocks have trended consistently upwards. Here’s a chart showing the S&P 500 on a log scale:

(Shortform note: Long-term stock charts are often shown in log scale since they better reflect percentage changes and compounded growth, as opposed to changes in absolute values.)

Over the long term, stocks have tended to rise—in the history of the S&P 500, the annual return is roughly 10%, without adjusting for inflation. Graham suggests this consistent long-term performance supports his advice that all portfolios should have a portion in stocks.

However, he heavily cautions against simplistically extrapolating from the past, and against the delusion that stocks will always increase and so are worth investing in at any time, at any price. These conditions tend to breed wanton overpricing, which tends to invite a steep correction downward.

While the general trend is up and to the right, in the short-term, stocks fluctuate. Look more closely at the chart, and you’ll see more detail:

- A major collapse in 1929, followed by fluctuations up until 1950. The S&P 500 would not reach the heights of 1929 until 25 years later.

- A strong growth period from 1950 to 1965.

- A period of relative flatness from 1965 to 1975.

- Generally strong growth from 1975 to the 2000 dotcom crash, with periodic recessions in between.

As we think about investments today, we don’t have the benefit of future information, and so it becomes important to assess whether the stock market is expensive or cheap.

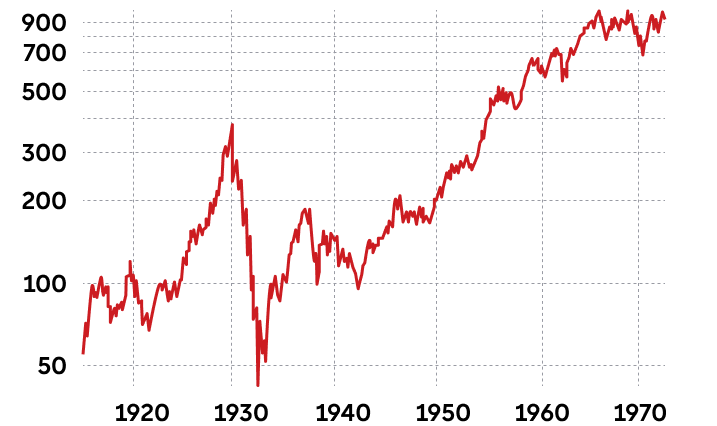

Shortform Exclusive: Inflation-Adjusted Returns

The book doesn’t address inflation in this chapter, but the inflation-adjusted stock returns have a significantly different shape:

Notably, during the highly inflationary 1970s and early 1980s, the stock market halved in real value, even though the absolute price stayed relatively flat. After adjusting for inflation, the annual return of the S&P 500 decreases from 10% to 7%.

Metrics for Evaluating the Stock Market

Of course, when investing today, you don’t have a stock chart for the future. You’ll need to assess the market to decide whether it’s cheap or expensive. Graham uses two major indicators of stocks in this discussion:

1) Price to Earnings ratio (P/E ratio)

This is the ratio of the stock price to the company’s earnings. If a company has earnings per share of $1, and its stock is selling at $10 per share, the P/E ratio is 10.

In general, a P/E ratio of 10 or below is low, and the stock is considered cheap. A P/E ratio of 20 or above is high (or the stock is expensive). (Shortform note: However, as discussed later, the P/E ratio is not by itself a good indicator of whether to buy a stock, since a failing company with poor future prospects will also have a low P/E ratio.)

2) Dividend yield, relative to bond yield

A stock’s dividend yield is the amount paid in annual dividends per share of stock, divided by its stock price. If a company pays $1 in dividends per share, and the stock price is $20, the dividend yield is 5%.

The bond yield is the return on a bond. Simplistically, if a bond costs $1,000 and pays $100 per year, the yield is 10%.

Comparing the stock’s dividend yield to the bond yield suggests whether stocks are likely to outperform bonds in the short-term, or vice versa. If the bond yield is notably higher than the stock’s dividend yield, it might indicate that stocks are overpriced.

Both of these indicators can be calculated for individual stocks, as well as for a collection of stocks or the stock market as a whole.

Graham’s Predictions

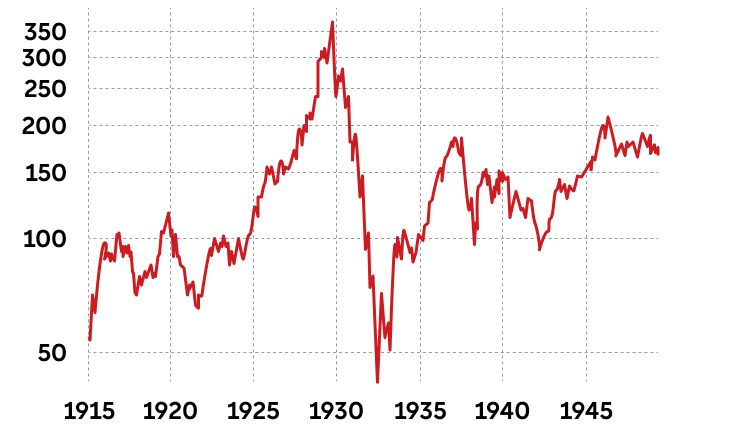

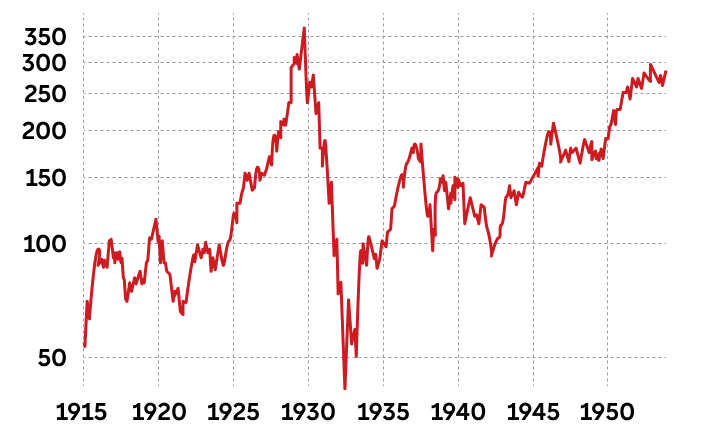

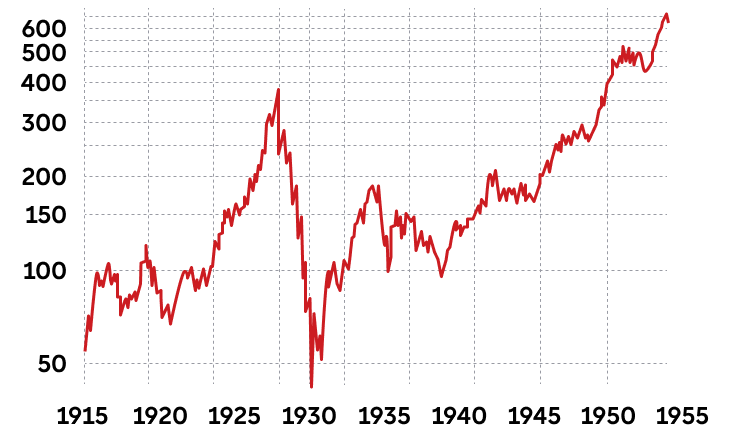

In each edition of The Intelligent Investor, Graham assessed then-current market conditions and declared whether the market was cheap or expensive. We’ll discuss his reasoning and how his predictions matched reality. (Shortform note: We’ve included stock charts of the Dow Jones Industrial Average up to each prediction time, to better show what was available to Graham at each point in writing.)

1948

Prediction: Stocks are not at too high a level.

- The ratio of stock price to the last 3 years of earnings is at 9.2x.

- The yield of stock dividend yield to bond yield is 2.1x.

Reality: From 1949 to 1953, the Dow gained 50%.

1953

Prediction: Stock prices are favorable, but prices have grown for longer than in most previous bull markets, and the price is historically high. Be cautious.

- P/E ratio is 10.2x.

- Dividend yield to bond yield is 1.8x.

Reality: The stock market grew 100% in the following five years. Graham admits they were too conservative in this edition.

1959

Prediction: The market is at an all-time high, and investors’ enthusiasm and momentum is likely to carry it to even greater heights. We’re in dangerous territory. Don’t delude yourself into thinking there will never be a downturn, and buying stocks is always profitable.

- P/E ratio is 17.6x

- Dividend yield to bond yield is 0.8x.

Reality: These were mixed results. The market grew to 1961, then fell rapidly in 1962, but quickly recovered into 1963 and grew from then on.

1964

Prediction: Be cautious. It appears the market is no longer held to traditional methods of valuation. We can’t rule out either extreme, that prices will continue growing by 50% or will suddenly collapse by 50%. If in doubt, reduce stocks to 50% of your portfolio.

- P/E ratio is 20.7x.

- Dividend yield to bond yield is 0.7x

Reality: The market fell to a notably low in 1970, then spent 1972 relatively close to 1965 levels. Graham feels this was appropriately cautious.

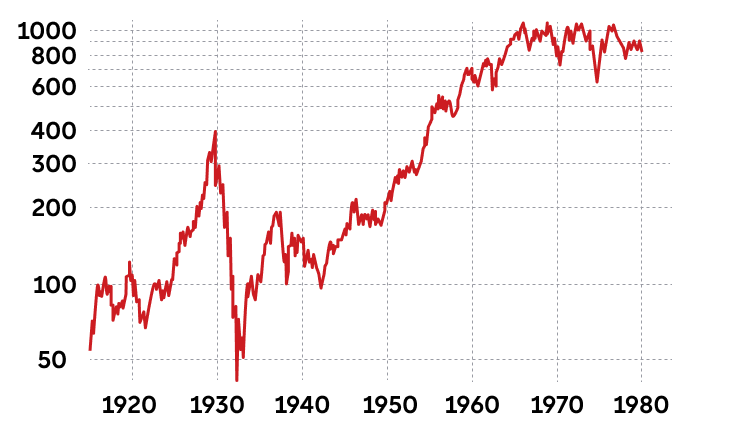

1971

Prediction: Stocks are still overvalued. There will likely be a major setback in stock value, or a brief bull market followed by an even larger setback.

- P/E ratio is 18.1x. This is lower than the recent high of 20.7x in 1963.

- However, the dividend yield to bond yield ratio is a dismal 0.41x, down from 2.1x in 1948. The situation has inverted, so that bonds are a much better investment than stocks.

Reality: The stock market suffered a major drop in 1973-1974, down 37% from the peak. Here’s a chart showing what happened after his last assessment:

Takeaways

Now that we’ve covered multiple historical data points, what’s important to take away from this?

1) Even experts like Graham have trouble picturing exactly what will happen in the future. At times Graham was too conservative in estimating how strongly stocks would grow; at others, he predicted a major setback that didn’t occur for quite some time. Beware of relying on so-called experts; make up your own mind through independent thinking.

2) Beware of relying too strongly on extrapolating from the past. Graham himself cautioned in 1953 that the market was at a historical high. The market grew by 100% in the following five years.

In commentary, Zweig notes that during the dotcom bubble, a slew of investment managers claimed this was an unprecedented new era of limitless growth, and they piled on each other with higher and higher price targets for the stock market. The stock market eventually fell over 30%, with some stocks losing over 99% of its value.

3) Practice contrarian thinking. If someone says stocks will always go up, ask, “why? If everyone buys stock according to this belief, then won’t stock prices be unreasonably high? And if companies can only earn finite amounts of profit, won’t the stock price at some point exceed a reasonable value for the company?”

In fact, Zweig suggests, the more enthusiastic investors are, the more likely a setback is to occur. And the more that stocks fall out of favor after a large shock, the more likely it’s a buying opportunity.

Chapter 4-5: The Defensive Investor

With some market fundamentals covered, we’ll now discuss the two major types of investors: defensive investors in this chapter, and aggressive investors in the next.

Defensive investors want to avoid spending too much time on investing. They like simplicity and don’t love thinking about investments or money. Their goal is to perform on average in line with the market, and to avoid serious mistakes.

We’ll cover how the defensive investor should invest, both from a philosophical point of view on how to behave and a tactical point of view on what stocks and bonds to buy.

How Should Defensive Investors Invest?

Graham’s recommendation is to split investments between stocks and bonds. The default split is 50-50 between stocks and bonds. This allows you to participate in both the gains of stocks as well as the relative safety of bonds.

At times, you can shift your balance in favor of stocks or bonds. If you feel stocks are overpriced and due for a downturn, you can shift your investment to 25% in stocks and 75% in bonds. Likewise, after a steep market downturn or when stocks are cheap, you might shift to 75% in stocks and 25% in bonds. But Graham advises no more than a 75-25 imbalance.

Why is this? Why not put 100% of your investment into bonds? Three reasons:

- Stocks on average rise faster than inflation, whereas bonds might not, so holding stocks better protects against inflation.

- Stocks tend to have better returns (though this isn’t always true; if interest rates are very high, as they were in parts of the 1970s and early 80s, bonds may provide better returns).

- If you invest 100% into bonds, but the stock market grows tremendously, you’d feel regret on missing out.

And why not 100% into stocks?

- Stocks don’t always outperform bonds at all times. At the time of Graham’s last revision in 1973, bonds were outperforming stocks. Keeping a balance helps you weather a variety of economic conditions.

- Stocks fluctuate much more than bonds do, and the wild oscillations of a 100% stock portfolio may test the investor’s equanimity. A terrible mistake you can make as an investor is to sell as the stock market craters, and buy at the peak of its hype. Holding a minimum 25% in bonds gives some psychological cushion against stock market falls.

In short, keeping a standard split is simple, provides adequate returns, and prevents your emotions from sabotaging yourself.

The Myth of Age

There’s a common rule of thumb that your split between stocks and bonds should depend on your age: subtract your age from 100, and that is the percentage that should be held in stocks.

But Graham never mentions age in his advice, for good reason. Zweig supports this point, arguing age shouldn’t affect your investment decisions—your personal circumstances are what matter.

In particular, you can feel more comfortable holding more stocks if:

- You do not need to sell your stocks at inopportune times to support your living costs.

- You can withstand severe drops in the stock market.

- You do not need your investments to provide cash income. Generally, bonds provide more in interest payments than stocks do in dividends.

Consider two different situations that buck the common wisdom:

- A retired 80-year-old who has a pension to cover all her living expenses, $2 million in assets, and grandchildren. Investing mostly in bonds is a mistake—she doesn’t need to rely on investments for income. Furthermore, her descendants, who will inherit her assets, have decades of investment in their timeline, and stocks will provide better returns on that timeline.

- A working 30-year-old who has $50,000 and is saving up for his down payment on a house. It’d be silly to put all of that in the stock market—if the stock market fell, he’d have to change his life plans.

Portfolio Rebalancing

Over time, as your investment values fluctuate, the proportion between stocks and bonds will deviate from your desired ratio. For example, if you start with $10,000 and a 50-50 split between stocks and bonds, over time you may end up with $6,500 in stocks and $5,500 in bonds, leading to a 54:46 split. At this time, you should “rebalance” your portfolio to return to 50-50. You can do this by selling stocks and buying bonds, or if you have more money to invest, you would buy relatively more bonds than stocks in this round of investment to return to a 50-50 split.

You shouldn’t rebalance more frequently than once or twice a year. If you’re checking your investments on a daily basis and spending hours per week, you’re getting too involved to be a defensive investor, and your emotions will likely start ruling your decisions.

Dollar-Cost Averaging

If you have a lump sum of money, how would you invest it? Some investors, tempted to get higher than market returns, might choose to “time the market,” waiting until a market dip to invest. The very likely risk is that the investor turns out to be entirely wrong, either losing out on gains as the market rises, or mistiming the bottom.

In contrast, Graham recommends dollar-cost averaging—split up the lump sum into multiple investments of equal amounts, distributed over a longer period of time (such as every month or quarter). This is a straightforward strategy that requires minimum thinking and emotional investment.

Graham argues for the psychological benefits of dollar-cost averaging: you remain emotionally detached from the swings of the market. Regardless of whether prices are up or down, you invest the same amount.

Practically, this prevents you from overreacting in bad directions:

- When the stock market crashes, most people become fearful about investing, yet this is the point at which stocks are cheapest. Dollar-cost averaging forces you to invest the same amount.

- Likewise, in a strong bull market, you might be tempted to buy stocks at steep prices. Dollar-cost averaging prevents you from getting carried away and investing more than is wise.

Psychologically, dollar-cost averaging helps you avoid the delusion that you can predict the market. Zweig notes that your response to any investment question should be “I don’t know and I don’t care.”

- Are technology stocks worth doubling down on? Is this hot new company worth investing in at its premium price? “I don’t know and I don’t care”—if you invest in mutual funds, they already capture a large part of most industries, and any hot company that succeeds will be a part of your portfolio soon enough.

- Is the stock market going to rise or fall in the next month? “I don’t know and I don’t care”—if it rises, your existing investments will capture that gain; if it falls, you will invest more later at a lower price.

(Shortform note: Dollar-cost averaging has been studied extensively, with both strong advocates and critics. Critics argue that it leads to subpar performance—in short, if the expected value of your investment is positive, then you should invest as early as possible to capture that expected value. Proponents of dollar-cost averaging suggest that, even if it doesn’t yield superior returns, it carries benefits in psychological ease and simplicity.)

What Stocks and Bonds to Buy?

Now that you understand the general split between stocks and bonds, what do you actually buy? Graham spends a few chapters giving advice on choosing specific individual bonds and stocks because, in the mid-20th century, those were the only options available to investors.

Since then, a large number of low-cost mutual funds have become popular. These funds hold a wide basket of assets, such as stocks and bonds, thus providing diversification with minimal effort. (Shortform note: For instance, Vanguard has a fund for the entire US stock market, as well as a fund for short-term Treasury bills. When you buy a share of such a fund, you essentially hold a small piece of everything the fund holds.) Such diversification makes dollar-cost averaging and rebalancing easy to execute, since you only need to buy one fund instead of balancing across dozens of stocks.

And in contrast to high-cost mutual funds in the 20th century, where annual fees might be as high as 1-2% of your investment, these days competition has driven the fees down to the range of 0.05% (a $10,000 investment would cost just $5 per year).

Graham was a big fan of index funds, and the modern defensive investor may do well simply by investing in index funds at Graham’s recommended split. But for comprehensiveness, we’ll cover his advice to the defensive investor for choosing specific stocks and bonds.

What Stocks to Buy?

For any investor, the classic mistakes in buying stocks are:

- Paying too high a price for a stock: This is especially risky in 1) strong bull markets, when the market seems like it can only rise with no possibility of a downturn, or 2) for hot stocks, where speculators drive up the price expecting the company to outperform in the long term.

- Withdrawing from the stock market after a steep crash, when most people view stocks as too risky. At this time, stocks are especially cheap.

To counter these mistakes, Graham issues four simple rules for choosing stocks:

1. Diversify, but not excessively.

Graham advises holding at least 10 and at most 30 stocks.

2. Buy large, prominent companies with conservative financing.

Let’s define each of the three terms:

- Large: In 1973, Graham defined large as having at least $50 million in assets or revenue. In modern commentary, Zweig suggests the bar is companies with at least $10 billion in market capitalization.

- Prominent: The company should be a leader in its industry, and be in the top 25% by size.

- Conservative financing: The company’s market capitalization should be no more than double its book value.

(Shortform note: Critics argue that book value is unreliable in modern times, since book value excludes the value of intangible assets like intellectual property or brand value. Thus, relying on book value alone would eliminate a swath of promising investments.)

3. Buy companies with a record of continuous dividend payments.

In 1973, Graham argued for companies that regularly paid dividends over the past 20 years. In recent times, companies have paid dividends much less regularly, so Zweig adjusts the time frame to the past 10 years.

4. Impose a price maximum on stocks you buy.

Graham argues for a maximum per-share price of 25 times average earnings over the past 7 years, or 20 times earnings over the past 12 months.

Notably, this rule excludes hot “growth stocks,” for good reason. Growth stocks often represent new companies that are growing rapidly but are unprofitable or have only meager earnings. Thus, their price-to-earnings ratio may be far above 20 times. Graham argues that these stocks are too risky for the defensive investor—without thorough analysis, a defensive investor is very unlikely to repeatedly pick the right stocks at the right times.

Finally, don’t buy common stock for its dividend income alone. The stock price must still be reasonable, and the company should be fundamentally sound.

We’ll return to more technical guidance on how to pick stocks in Chapters 14-15, after we cover more fundamentals of stock analysis and market mindset.

Don’t “Buy What You Know”

In his commentary, Zweig cautions against the common wisdom of “buy what you know.” The premise of “buy what you know” is that, as an ordinary consumer, you know what brands and products you like, and in this sense you might know more about the company than professional stock analysts. Thus, you should buy stocks of companies you like.

Of course, this simple-minded view violates Graham’s universal principles of considering the underlying value of the stock, and the stock price in relation to its value. If you were a disciplined investor, you would consider whether the stock was overpriced, regardless of how much you liked the company emotionally.

This applies generally to being complacent about what you’re familiar with. The more you think you know about something, the less you are to probe for real weaknesses.

Notably, this applies to people owning their own company’s stock in their retirement portfolios. Does it ever make sense to have a third of your entire stock portfolio in a single company? If not, then why would it make sense to invest it in your employer?

What Bonds Should You Buy?

Shortform Exclusive: Introduction to Bonds

(Graham skips over explaining what bonds are, assuming the reader already has knowledge. We wrote this introduction in case you’re unfamiliar.)

Bonds represent loans made by an investor to a borrower. As an investor, you can buy bonds from companies, municipalities, states, and national governments. When you buy a bond, you become a creditor—the bond issuer owes you money.

A bond consists of a few components:

- The principal: the amount of money that is borrowed, also known as the “face value”

- The coupon: the interest rate that is paid to bondholders.

- The maturity date: the date at which the principal will be paid back.

For example, say today you buy a treasury bond from the US federal government with a principal of $10,000. The term is 20 years, with a coupon rate of 4%. Every year, you will receive $400 in interest payments. In 20 years, the government will pay you back $10,000.

The bond is also tradeable. You can buy the bond from the government, then sell it to another investor. You aren’t required to hold onto a bond until the maturity date.

The bond therefore has a market price that depends on outside circumstances, particularly the market interest rates. Once it’s issued, a bond is a fixed instrument with defined terms—it will pay certain amounts at certain dates. The fixed amount that bond pays can have changing values in different periods:

- If the interest rate in the larger market declines, the price of a bond increases. For example, say you have a bond with a 4% coupon while overall interest rates are at 2%. The bond is paying out more than current interest rates, and it thus becomes more valuable. The price of this bond might significantly exceed the $10,000 in face value.

- Likewise, if the overall interest rate increases, the price of a bond decreases. For example, if interest rates rise to 6%, there are better opportunities to invest elsewhere than in the 4% bond. The price of a bond might fall much lower than the $10,000 in face value.

There are many more complexities to bonds, but this should suffice to build an intuition for how bonds work.

Zweig’s Commentary on Bonds

In his modern commentary, Zweig offers the following additional tips:

- Most bonds are sold in $10,000 lots, and you need at least 10 bonds to diversify away the risk of default. Therefore, unless you have $100,000 to invest in bonds, you should invest in bond funds instead. These diversify over a wide basket of bonds without your needing to do individual research.

- If you really want to buy individual bonds, instead of buying short-term or long-term bonds, strike the middle: 5-10 year maturity dates. These have more dampened fluctuations than long-term bond prices, while they capture more upside than short-term bonds.

Types of Bonds

When deciding what bonds to buy, there are more considerations:

- Tax status: some bonds provide tax-free coupon income, while others are taxable.

- Maturity date: are bonds with shorter terms or longer terms better?

- Risk of default: a borrower defaults when it’s unable to make payments on its loans. The borrower may ultimately declare bankruptcy, and the bond may lose a substantial part of its value. Thus, higher-risk borrowers can only issue bonds at higher interest rates—its lenders demand the extra payments to compensate for the higher risk of bankruptcy.

For tax status, the question is straightforward—a taxable bond should compensate for your income tax bracket with a higher coupon. For example, if your tax bracket is 30%, then a tax-free bond with a 7% coupon and a taxable bond with a 10% coupon are equivalent. Thus, a tax-free bond with a coupon rate higher than 7% would be relatively more attractive, and likewise for a taxable bond with a coupon higher than 10%.

Don’t buy tax-free bonds in your retirement accounts, like your 401(k) or IRA. In these tax-advantaged accounts, you should hold taxable bonds instead.

To address the other issues, Graham provides an overview of the major types of bonds. While the yields for all types of bonds fluctuate over time, the general properties stay consistent.

US Savings Bonds (Series E)

- Maturity: Up to 30 years

- Federal tax: Yes | State tax: No

- Risk of default: Very low

Notes:

- Allows for redemption at any time. Graham notes that this unique flexibility could compensate for lower returns.

- Graham discusses Series H bonds, but these were discontinued in the early 2000s.

Treasury Bonds

- Maturity:

- Treasury bills: Up to one year

- Treasury notes: Between 2 and 10 years

- Treasury bonds: 30 years

- Federal tax: Yes | State tax: No

- Risk of default: Very low

State and Municipal Bonds

- Maturity: 1 to 30 years or more

- Federal tax: No | State tax: Yes (unless in state of issue)

- Risk of default: Moderate (check credit ratings—AAA to A is safe)

Corporation Bonds

- Maturity: 1 to 10 years or more

- Federal tax: Yes | State tax: Yes

- Risk of default: Moderate to high (check credit ratings)

Notes:

- Higher-yielding “junk bonds” provide a higher return with higher risk of default. Graham advises defensive investors to steer clear of these, since they require detailed study to find bargains.

Preferred Stocks

Like corporation bonds, preferred stocks are issued by companies, but they’re a hybrid of common stock and bonds:

- They pay a fixed dividend rate, but only if the company decides to pay a dividend. If the company can’t or doesn’t pay dividends, the preferred stock doesn’t produce any payments.

- Because the dividend is fixed, it caps the profits available to the preferred stock holder. Common stock does not have this cap.

- In a company’s liquidation, preferred stock has more senior rights than common stock, but lower than bonds and creditors.

In Graham’s view, this is the worst of both worlds: limited upside combined with higher risk. Thus, he advises defensive investors to stay away from preferred stock. He does note that other corporations might consider buying preferred stock, since corporations pay a lower tax rate on dividends than on income payments from bonds.

Income Bonds

Income bonds are issued by companies. With income bonds, interest isn’t guaranteed to be paid, unless the company has enough earnings to pay it. A company that pays interest on these bonds can deduct it from its taxable income, which makes it an especially cheap form of capital.

Graham notes that these should be used more often by corporations, but still have a historical stigma as being issued by financially weak companies.

Chapter 6: The Aggressive Investor, Generally

In contrast to defensive investors, who want to minimize time and get acceptable results, aggressive investors want to devote serious time to investment research to achieve better returns than average.

When describing these investors as “aggressive,” Graham is not urging any carelessness or impulsiveness, despite general connotations of the term “aggressive.” In stark contrast, aggressive investors should methodically value potential investments, be patient for bargains, and maintain level-headedness when the market is reactive in either direction.

(Shortform note: Graham uses the terms “enterprising investor” and “aggressive investor” interchangeably—we use “aggressive” since it’s the more well-known of the two terms.)

Expectations for the Aggressive Investor

Effort Required of the Aggressive Investor

To be successful as an aggressive investor, you must devote your full effort and attention to the task. You should view your investing as equivalent to operating a full business—just as you can’t be half a business operator, you can’t be half an aggressive investor and half a passive investor.

Since most people can’t put in this effort, they should become defensive investors instead.

Expected Gains of the Aggressive Investor

How much in gains should a successful aggressive investor expect? The author says that an additional 5% per year, before taxes, is necessary to be worth the effort of all the research and work. (Shortform note: Graham notes repeatedly that good investors should not aim for stratospheric results, but rather modest and consistent returns over the long term. Due to compounding returns, an extra 5% a year makes a huge difference over time.)

A Warning from Graham

(Shortform note: This section originally came from Chapter 15.)

The task of beating the market is a difficult one, and Graham issues a caution—the evidence strongly suggests that most professional money managers do not beat the overall market in the long term, after deducting fees. These funds employ highly intelligent and motivated people who dedicate their entire working days to researching and choosing individual securities. Yet even they can’t outperform the S&P 500.

Why is it so difficult to beat the market? Graham offers two possible reasons:

Reason 1: The current stock price already has all existing information “priced in,” and from this point stock market movements are essentially unpredictable.

There are countless opportunistic investors and investment firms that behave like an aggressive investor—they study a company’s historical performance and future prospects, try to identify bargains and overpriced stocks, and invest accordingly. When the market is made up of many thousands of such people, the market price for a security already reflects the consensus opinion of the company’s value.

From this point on, any developments that affect stock price are unpredictable. When you try to predict the unpredictable, your chances of succeeding in the long term are slim.

Reason 2: Most investors have a bad strategy. If you adopt a non-consensus strategy, you might be able to beat them.

Most money managers might have a consistent problem in how they make investments. For instance, they might believe that a promising company’s stock is worth buying, no matter how high the price. They might also believe that certain industries and companies are toxic wastelands to be avoided, no matter how low the price.

In practice, no company’s stock price rises perpetually, and many companies that have fallen into temporary misfortune recover company performance and stock price.

If most traders in the market believe such ideas, then there can exist opportunities that are ignored by the rest of the market. Graham’s personal record as a consistently successful investor, as well as the records of his students such as Warren Buffett, suggests that such opportunities do exist.

How Should Aggressive Investors Invest, Generally?

To beat the overall market, the aggressive investor needs to practice a disciplined approach that is unpopular in the larger market.

Why unpopular? Investing is so competitive that any straightforward strategy that actually works consistently will quickly be adopted by the rest of the market, and the profits will evaporate. Graham cites an example from 1949, where buying the Dow Jones index below its intrinsic value and selling it above intrinsic value provided consistent returns over much of the past century. After 1949, this no longer worked—either because people adopted the strategy and thus bid up stock prices past the point where the strategy worked; or the strategy was illusory to begin with.

After all these warnings, what strategy can be used, then? In essence, Graham’s strategy is to use a framework to value companies reliably, then identify companies that are priced lower than their fair value. In other words, buy a company when it’s priced more cheaply than it’s worth. That’s what most of the remainder of the book is about.

Why does this strategy not lose its advantage over time, like other strategies? Graham suggests a few reasons:

- Speculators trade so erratically that, at any time, there will always be stocks that are overvalued and undervalued.

- Companies and entire industries may be undervalued simply because they fall out of fashion.

- Despite the claims of the efficient market hypothesis, there will remain pricing inefficiencies in the market, particularly because market movements are made of people following their own flawed psychology and of such people mimicking each other.

(Shortform note: The implication is that the patient, methodical, emotionally composed method suggested by Graham will continue to be unpopular. Most speculators are swayed by popular opinion, have mood swings, look for simple solutions, and are impatient for riches. Few will have calm control over their psychology and take on the burdensome task of thorough research, and so few will enjoy the fruits of the strategy.)

Enthusiasm is great for endeavors outside of investing. In investing, it will ruin you. Here you need self-control. You cannot let other people’s opinions and emotions sway your own.

Chapter 7: The Aggressive Investor, Specifically

With the general mindset established, we can now cover the specific choices of the aggressive investor. While the defensive investor can earn market returns simply by investing in general mutual funds, the aggressive investor needs to seek pointed opportunities to be above average.

Asset Classes to Avoid

An aggressive investor willing to do a lot of work will likely be more interested in a broad array of asset classes. If you know what you’re doing and can find good opportunities, you’ll likely enter areas that defensive investors should stay clear of.

However, Graham cautions against a set of instruments that even aggressive investors should be skeptical of. An investor’s success is defined just as much by what he chooses not to do as by what he does.

For the below issues, the aggressive investor should be cautious and scrutinize the security before investing.

- Be careful not to get carried away by the promise of higher returns while ignoring the risk and inadequate margin of safety.

- Avoid buying each of these securities at full prices. Consider buying them only at steep discounts (where prices are below two-thirds of their fundamental value).

In any of these classes, you may find clear bargains, but you need to be more careful than usual.

Defensive investors should avoid these entirely.

Second-Grade Bonds (Junk Bonds)

Companies with a sound position offer first-rate corporate bonds. More precarious companies with lower credit ratings issue lower-grade bonds (also known as “junk bonds”) with a higher interest rate.

One heuristic Graham uses to determine the grade of a bond is the ratio of company earnings to interest charges.

- In the railroad industry, for instance, he prefers that a company earn at least 5 times the annual interest charge; less healthy companies might only have enough earnings to cover 1 times the interest charge.

- In modern times, WorldCom sold $11.9 billion of bonds in 2001. However, its pretax income fell short of covering its interest charges by $4 billion. It could only pay off its interest by borrowing even more money. While its bonds did offer 8% yields for a few months, WorldCom went bankrupt in 2002.

It may be tempting to buy these lower-grade bonds purely for the sake of a higher yield. But Graham cautions that it’s unwise to seek attractive yield without adequate safety. The companies issuing lower-grade bonds have a higher chance of default and you may actually lose your entire principal, merely for an extra 1-2% of yield.

Therefore, a second-grade bond selling at par value is usually a bad investment. It’s better to buy lower-grade bonds at steep discounts. Because these bonds tend to rise and fall with markets, a patient investor will be able to find good deals.

In his modern commentary, Zweig mentions there are now junk-bond funds that allow more diversification across dozens of different junk bonds. While they do outperform Treasury bonds on paper, they tend to charge high fees.

Foreign Government Bonds

The trouble with owning foreign government bonds is that the owner of these bonds has no legal way of enforcing them. Unlike domestic companies, foreign governments are outside the domestic legal system.

Historically, foreign bonds have also had a poor history for much of the 20th century until at least when Graham wrote this book. For instance, Cuba issued bonds that reached a high of 117 in 1953, then defaulted on those bonds and brought the price down to 20 in 1963.

In his commentary, Zweig mentions there are now emerging-market mutual funds that, once again, allow diversification across foreign bonds. He notes that these have the useful property of not correlating strongly with the US stock market and may be useful as diversification, but don’t put more than 10% of total bond holdings into them.

New Stock Offerings (IPOs) and New Issues

In an initial public offering (IPO) or a new stock offering, privately owned companies “go public” and sell their stock to the public. This allows the company to sell their stock for cash, raising funds for further investment and allowing stockholders to cash out.

Not all new issues should categorically be dismissed, but they deserve extra scrutiny for two reasons:

- The underwriters of the IPO (commonly investment banks) own a large portion of shares, so they have a passionate interest in painting the best picture of the company to pump up the price.