1-Page Summary

Important and memorable moments—the grand events of your life that make you who you are, like your wedding or the first time you met your grandchild—are naturally meaningful to you. But smaller, everyday experiences—like a day at the beach or a fulfilling conversation with a friend—hold just as much power.

According to authors Chip and Dan Heath, these daily defining moments—short, memorable experiences that are meaningful to you—are happening around you constantly. You can learn to recognize their potential and apply time, effort, and strategic thought to turn them into defining moments that shape memories or change perceptions.

Investing in these smaller moments can enhance your life in myriad ways. A well-engineered defining moment can have a tangible outcome like increased revenue from satisfied clients or improved test scores from motivated students. Other times, you’ll create defining moments with a more personal objective—deeper relationships with your friends and family, a better understanding of yourself and your values and motivations, or mentees who are confident in taking on new challenges.

(Shortform note: Several reviewers of The Power of Moments questioned whether defining moments can ever feel “real” if they’re engineered. This criticism misses a central idea of the Heaths’ argument—defining moments already exist and therefore are genuine. “Engineering” moments doesn’t mean staging a false event—it simply means giving attention and effort to important events that might otherwise go undetected.)

What Makes for a Defining Moment

Before they get into different methods of creating such moments, the Heaths discuss two foundational aspects of defining moments: They’re both meaningful and memorable.

The Four Elements That Create Meaning

To engineer meaning, the Heaths say your moment should incorporate at least one of four emotion-boosting elements:

- Elevation: The moment is elevated beyond everyday experience, either through sensory pleasures or the element of surprise.

- Insight: The moment helps you discover something new about the world or yourself. Often, these moments have a transformative and influential effect on the course of your life.

- Pride: The moment gives you a sense of validation around your achievements or a sense of pride in your actions.

- Connection: The moment makes you feel more deeply connected to whoever shares it with you, and strengthens your relationship with them.

Shortform Commentary: Where These Four Elements Come From

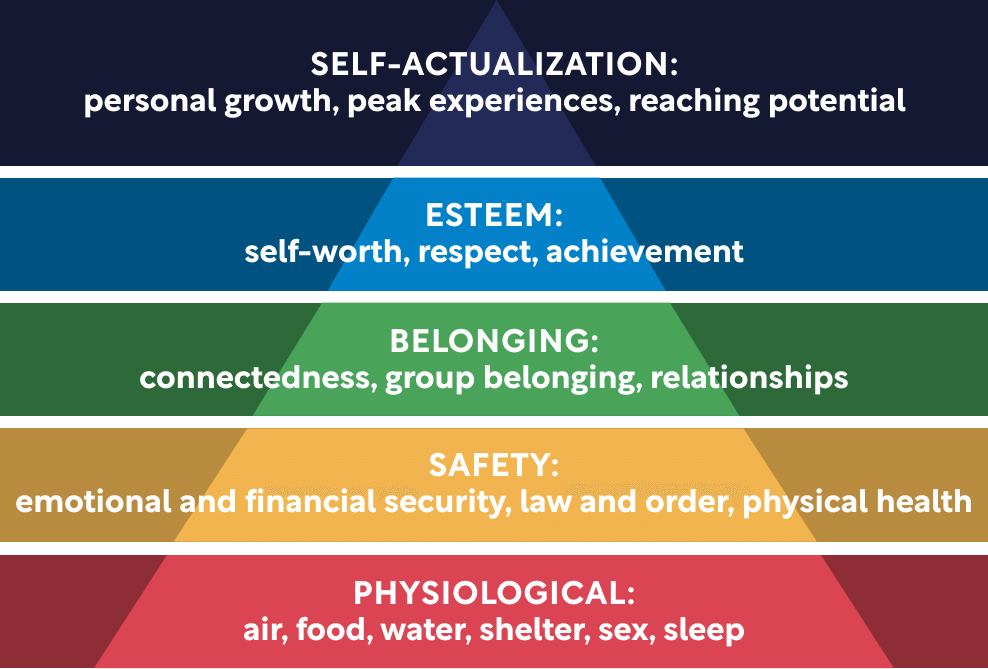

The Heaths don’t note the exact research that led them to these four elements, but their ideas align closely with those of psychologist Abraham Maslow. Maslow is well-known for his “hierarchy of needs”, which describes the requirements for a person to become self-actualizing—constantly growing, discovering, and finding meaning in her life. There are five tiers to the hierarchy:

- Level 1: physiological needs such as food, water, and shelter.

- Level 2: safety needs such as physical health or law and order.

- Level 3: needs of belonging such as relationships and connectedness.

- Level 4: needs of esteem such as self-worth, respect, and achievement.

- Level 5: needs of self-actualization such as personal growth, peak experiences, and reaching your potential.

The Heaths’ four elements align with Maslow’s three “higher needs” of self-actualization, esteem, and belonging:

- Elevation: Self-actualizing people are capable of experiencing “transcendent” moments, or moments elevated above the everyday experience that create a sense of delight, wonder, and surprise.

- Insight: Insight is the core of the self-actualization tier of the hierarchy. As we’ll discuss, insight leads to personal growth, discovery, and a realization of your potential.

- Pride: Pride is the core of the esteem tier of the hierarchy. As we’ll discuss, pride helps you feel achievement and respect and increases your sense of self-worth.

- Connection: Connection is the core of the belonging tier of the hierarchy. As we’ll discuss, connection can strengthen your bonds with groups or in personal relationships.

In short, elevation, insight, pride, and connection are the elements that allow humans to live, not simply survive.

What Makes a Moment Memorable?

While the Heaths discuss what makes a moment meaningful, they don’t delve into what makes it memorable, which is the second characteristic of a defining moment. In order to be memorable, most defining moments should have an aspect of novelty or unexpectedness. Unexpectedness is important because when you experience emotions in a moment of surprise, you experience them more intensely than you would in an “everyday” situation.

- For instance, the joy of spending time with your friends isn’t as intense as the joy of being surprised with a puppy for your birthday.

These high-intensity emotions send a signal to your brain that something important is happening—your brain responds by paying more attention than usual to the event at hand, while blocking out unrelated, external stimuli.

Moments Defined by Elevation

Moments defined by elevation transcend everyday patterns and impart positive feelings like delight, motivation, and engagement. In short, elevated moments are the positive peaks that you look back on fondly.

(Shortform note: In his hierarchy, Maslow lists “peak experiences'' as a component of the highest need, self-actualization. Maslow described peak experiences as small, everyday events that give us a feeling of newness or delight—in other words, as with elevated moments, we transcend everyday dullness.)

There are three ways to use elevation: Increase sensory pleasure, raise the stakes, and go off script with strategic surprise. Successful, memorable moments incorporate at least two of these methods.

Strategy 1: Increase Sensory Pleasure

Increasing sensory pleasure depends on making a moment look, feel, taste, or sound better than what you’re used to. For instance, getting dressed up to go out to a fancy restaurant looks, feels, and tastes different from eating in your sweatpants on the couch.

(Shortform note: The Heaths don’t discuss which sensory appeals work best, but numerous studies have concluded that memory links most strongly to your sense of smell. You can use this information to engineer small, special moments in a variety of contexts. For example, you might wear a certain “date night” perfume or cologne to make outings with your partner feel more special, or bake a certain type of cookie every Friday afternoon with your kids—each time you smell these particular scents, you’ll recall happy memories of your experiences.)

Strategy 2: Heighten the Stakes

The second way to elevate a moment is to raise the stakes. The Heaths explain that adding high stakes to a situation makes an otherwise flat, unengaging experience into a standout, exciting experience—for instance when you look back at your high school career, you’ll more likely remember your debate team championship than your algebra classes.

(Shortform note: One reason that high-stakes experiences stand out in your memory may be that the prospect of a high reward forces your brain to use long-term memory to “help out” your short-term working memory. As a result, your attention is more fully focused on the event—your brain re-engages in order to process all the information you’re taking in.)

Strategy 3: Go Off Script

The last method of elevating a moment is going off script, which the Heaths define as acting in a way that goes against what people expect. Meaningfully going off script doesn’t mean completely upending the scripts of your life. Memorable experiences are not wholly amazing—they’re largely mundane, with one or two exceptional peaks. Your goal, then, is to deliberately punctuate overall familiar and comfortable scripts with one or two strategic surprises.

(Shortform note: These strategic surprises are surprises that break behavioral patterns (or scripts) in a way that challenges assumptions about what comes next and draws the audience in.)

Example: The Difference Between Easy Surprises and Strategic Surprises

You want to make your weekly HR meeting more engaging. There are two ways you might go about it:

- Scenario A: You bring cupcakes to your meeting. It’s a nice gesture, but the surprise isn’t memorable or meaningful because the rest of the meeting unfolds the same way it always does.

- Scenario B: You examine your meeting’s script and decide to add a strategic surprise. You assign each of your team members a “new hire” role and send them out to interview their “new teams” for advice on maintaining work/life balance. At the end of the hour, your team members meet up and discuss their new insights. By going off your regular meeting script, you’ve elevated the experience and created a defining moment for your team members.

Moments Defined by Insight

The second element you can use to create defining moments is insight. Moments defined by insight inspire realizations or transformations that affect your future choices and actions. The Heaths suggest three ways you can spark meaningful, memorable insight: forcing others to confront an uncomfortable truth, putting yourself in situations where you must confront self-truths, and mentoring others.

1) Force Someone to Confront a Truth

The Heaths first explore how you can spark insight in others by setting up a moment in which they will be forced to confront an uncomfortable truth. They note three essential factors to making the moment defining:

- Have a clear conclusion: Know exactly what conclusion you want your audience to come to. This is often the easiest part of the process—you usually know exactly what truth needs revealing.

- Operate on a short time frame: Create a situation that will guide your audience to their discovery over a matter of minutes or hours, or even more immediately.

- Allow audience discovery: Let the audience discover the conclusion themselves, instead of telling them what to do.

These factors result in an “aha! moment,” or what psychologist Roy Baumeister dubbed the crystallization of discontent: a sudden moment in which any vague negativity or discomfort you’re feeling suddenly crystallizes in a pattern—you discover links between seemingly unrelated issues and the core problem becomes startlingly clear.

Why These Three Factors?

These three factors are crucial to creating insight because together, they replicate the conditions of a spontaneous crystallization of discontent. In her book Radical Acceptance, author Tara Brach discusses the Alcoholics Anonymous program, which notes that an addict begins changing when they hit rock bottom, an experience that echoes the Heaths’ three factors:

They realize that their lives are not within their control (an instantaneous realization, or a short timeline).

They understand that they must make a change to their lifestyle (a clear conclusion).

They have to come to this realization on their own—addiction support organizations stress that the addict is the only person who can take on the recovery process. In other words, they can’t get help until they understand the problem and decide to treat it themselves.

Example: Get Your Boss to See a Problem

Imagine that you work on the website design of a major retailer. You know the site isn’t user-friendly, but you’re not able to get your higher-ups to approve funding to do a UX overhaul. You arrange a one-hour meeting with them, where you pull up a retail website and ask everyone to accomplish a simple task, such as making a purchase or leaving a review.

It quickly becomes obvious that the site is an unusable mess and your higher-ups become frustrated. You agree with their frustrations and then make your big reveal: except for the products, the website and its functions are an exact copy of your company’s website. This is how clients feel when they are interacting with your site. Your higher-ups have their aha! moment and approve funding for your project.

2) Set Up a Situation for Self-Insight

The Heaths explain that using insight to create defining moments for yourself depends on pushing your boundaries—you must put yourself in situations that expose you to the possibility of failure. This is because the process of stepping outside of your comfort zone and risking failure leads to what psychologists call “self-insight”: an understanding of your values, abilities, goals, and motivations.

When you put yourself in risky situations, either you will succeed or you will fail. While success is certainly a reason to celebrate, keep in mind that failures—and the valuable learning opportunities they offer—should be celebrated as well.

How Failure Helps Us Learn About Ourselves

Barbara Frederickson and Daniel Kahneman (author of Thinking, Fast and Slow) found that the brain uses the emotional climaxes of experiences as “price tags” or reference points when recalling an experience. We use these reference points to determine whether repeating the experience is worth the “cost.” The negative emotions of failure create a reference point that acts as a type of warning: “If you continue on this route, it will cost you—you’ll feel these negative emotions again.”

- For example, you leave your corporate job to become the owner of a coffee shop. But the customers are demanding, the hours are long, and the income is unpredictable. One day, you realize, “This job is way too stressful. I miss the structure of the office.” The “cost” of owning a coffee shop is too high and not aligned with your values and motivations.

Shortform Commentary: Why You May Need a Mentor

Self-insight is a great reward for taking on new challenges, but actually pushing yourself into situations that come with a risk of failure can be very difficult, especially in the current global trend of people holding themselves to impossibly high standards of perfection. To break out of this mindset, it’s helpful to seek out a mentor who can support you through the process of leaving your comfort zone and exposing yourself to the possibility of failure.

(Note: Read our guide to Ryan Holiday’s Ego Is the Enemy to learn how to choose an appropriate mentor, ask them for their help, and develop a mutually beneficial relationship.)

The following section is geared toward mentors trying to push mentees into defining moments of self-insight. However, it can also help you, as a mentee, understand what makes for a great mentor and the benefits of seeking one out.

3) Push Others Into Self-Insight as a Mentor

As a mentor, your job is to push your mentee into situations that will spark her self-insight, providing the type of productive pressure that helps coax out her best self. The Heaths note that great mentors do four key things: Set high expectations, express confidence in the mentee, provide direction, and assure support. This formula sends the message, “I have high expectations, but I know you can reach them. I will present new challenges to you, and I will have your back if you fail.”

How the Mentorship Formula Cultivates a Growth Mindset

Your mentee can experience more instances of self-insight if you help her change the way she thinks about risk and failure. In Mindset, Carol S. Dweck explains that people typically have one of two mindsets:

Fixed mindset: The mindset that intelligence, ability, or talent can’t be learned or improved. People with this mindset avoid asking for help and have an intense fear of failure because they feel it defines them and exposes the limits of their abilities.

Growth mindset: The mindset that intelligence, ability, or talent can be trained or developed over time. People with this mindset are comfortable asking for help when they need it and overcome failure relatively easily because they see it as an opportunity to better understand themselves and to grow their abilities.

As a mentor, you want to help your mentee cultivate a growth mindset. The Heaths’ four-part formula helps touch on several aspects of guiding someone into this mindset:

High expectations and confidence: By being demanding and reassuring, you help them become more comfortable with challenging goals, but bolster their confidence in their ability to stretch themselves.

Direction: By giving your mentee a specific high-challenge project, you prevent them from defaulting to a project that seems easier or carries a lower risk of failure.

Support: Assuring your mentee of your support expresses to her that it’s okay to ask for your help—she doesn’t need to fear what you’ll think of her if she fails or can’t accomplish the goal alone.

Moments Defined by Pride

The third element you can use to create a defining moment is pride. Moments defined by pride surface and celebrate your best self—the “you” who earns recognition for your efforts, crushes ambitious goals, and acts with courage in situations that call for it. The Heaths suggest three strategies for multiplying instances of achievement and recognition:

- Build small, personally motivating “wins” into the journey toward a big goal.

- Recognize others’ efforts and make their progress visible.

- Prepare yourself to act with courage when necessary.

Strategy 1: Create and Celebrate Small Wins

The Heaths explain that everyone approaches goals differently: Some people might feel that accomplishing the goal is the only thing to be proud of, and others might think the journey to the goal is just as important as the goal itself. The Heaths suggest enhancing the instances of pride you feel while working toward a goal by adding small, personally motivating wins into the journey.

(Shortform note: Recall the fixed mindset and growth mindset discussion from Carol S. Dweck’s Mindset: Those with a fixed mindset often only care about the achievement of the goal, and those with a growth mindset can more easily see the value of the journey. The Heaths’ suggested strategy of celebrating small wins is helpful because it caters to both these mindsets. The frequent achievements cater to those with a fixed mindset, and the value placed on the pursuit of a goal caters to those with a growth mindset.)

Goals are often too large and ambiguous, and it’s all too easy to get lost along the way between Here and There or become discouraged or demotivated. Building small, achievable, and fun wins into the journey toward your goal serves several important purposes:

- Small wins are concrete and create a clear roadmap in the right direction.

- You’re more likely to stay engaged with small wins based on your particular motivations.

- You allow yourself multiple opportunities to feel good about your abilities.

(Shortform note: Studies have also shown that continuously celebrating small achievements is a fairly easy way to boost your overall happiness—it’s much easier to continue pursuing a goal when it feels good, or even fun, rather than like a chore.)

For example, if you want to lose weight, it’s best to abandon the old, vague roadmap of “eat healthy and exercise.” Think of small goals that feel like causes for celebration to you such as using the stairs instead of the elevator, cutting out soda for 30 days, going for a drink with friends when you hit 10,000 steps for the day, and logging 50 Zumba classes.

Strategy 2: Recognize Efforts and Progress

The Heaths note that there’s a common misconception that people who work hard are likely to feel proud of their work. It’s not so simple: Pride doesn’t come from hard work alone—it comes from the results of your hard work being noticed.

(Shortform note: Research shows that the strongest indicator of productivity is how a team member feels—if she feels positively toward her organization and herself and is motivated by her work, her productive performance will naturally increase. Team leaders, therefore, should focus their efforts on their team members’ feelings. The research determined that the most effective way to lift a team member’s mood is to make sure that she has a consistent sense that she’s making progress in meaningful work—what the researchers dubbed the progress principle.)

Recognition is the easiest way to use the progress principle to create pride for others. Pride that comes from recognition is especially memorable—largely because it’s so rarely practiced. When practicing recognition, your focus should be on the frequency of your praise, not the grandeur. People feel most satisfied when their efforts are being recognized consistently, not just when they accomplish a big goal.

(Shortform note: The progress principle specifies that team members who have a consistent sense of their progress experience heightened mood and productivity. Frequent recognition meets this need as well as reminding the team member that their work has meaning.)

Strategy 3: Prepare Yourself Mentally for Courage

The Heaths say that the third way to create pride is to act with courage—standing up for someone else, calling out injustice, or fighting for something we believe in.

(Shortform note: In Dare to Lead, Brené Brown—an expert on shame and vulnerability—explains “practicing courage” as developing unwavering integrity: A commitment to acting in alignment with what you understand, personally, to be the right thing to do—even in situations that make you feel vulnerable or exposed to the risk of failure.)

The Heaths note that while you might not have any control over when opportunities to act with courage appear, you do have control over how you react to these opportunities.

Usually, when you see something wrong or unjust, you don’t react right away, or at all—most people don’t naturally know how to immediately react to these situations. Without a specific planned response, we end up spending too much time deliberating what we should or could say or do, and miss the moment.

(Shortform note: In their book Switch, the Heaths put a name to this phenomenon of clamming up when faced with the task of making a choice—decision paralysis. When presented with numerous options or ambiguity, we’re predisposed to conserving our mental energy by defaulting to whatever decision feels easiest or most familiar, or not doing anything at all.)

To avoid decision paralysis, plan out exactly how you’d respond to an opportunity to act with courage—what the Heaths call “preloaded responses.” Preloaded responses are reactions that you’ve drilled into your memory so that they’re immediately ready in a situation that calls for it.

- For example, “When I see Bill and his friends mocking my sister at school, I will walk over, ask them to stop, and walk her to class. ”

While thinking of your preloaded responses, ask, “How can I get the right thing done?” This question asserts that you know what’s right and now must make it happen. It’s not a matter of what you should do, but what you will do.

Shortform Commentary: Support Preloaded Responses With Precommitments

Asserting that you know the right thing to do and planning out how to make it happen can apply to smaller, very personal moments of courage as well. Doing the right thing and acting with integrity matters, even if you’re doing it just for yourself. To help you with this, you might support your preloaded response with a precommitment—a pact you make with yourself about the way you’ll act in a certain situation.

In his book Indistractable, Nir Eyal outlines several ways you can use precommitments to push yourself into doing the right thing:

- Create social pressure: This kind of pact makes it harder to do something undesirable. You might make a precommitment with someone else—you’re not likely to break the pact because of the added pressure of being “watched” by someone else. For example, you might ask a friend to walk home from work with you every day so you don’t stop at the bar.

- Put money on the line: This kind of pact attaches money to your precommitment—if you break it, you lose the money. You might attach a $100 bill to your fridge and make a pact: If you buy beer, you have to burn the money.

- Identify with your future self: Commit to the identity you want to have by talking about yourself as someone who has that identity. For example, instead of saying, “I’m someone who’s trying to quit drinking,” you might say, “I’m someone who is quitting drinking.”

Moments Defined by Connection

The fourth element you can use to create a defining moment is connection. Moments defined by connection are experiences that can strengthen your group relationships or deepen your individual relationships.

Part 1: Use Connection to Strengthen Group Relationships

Defining moments for groups happen in experiences that create a shared meaning for everyone present—experiences that underscore the mission everyone is working toward together. These experiences are essential for reminding the group members that they’re united in something important and larger than themselves. The Heaths identify three steps to create moments of connection for groups: 1) Create a shared moment, 2) Allow for voluntary struggle, and 3) Reconnect members with their work’s meaning.

Why These Three Strategies Strengthen Groups

In his book The Culture Code, Daniel Coyle reveals three crucial psychological elements that solidify one’s place within a culture and contribute to the success of a group: safety, vulnerability, and purpose. Each of the Heaths’ three steps helps establish these elements:

Safety: Coyle describes safety as the feeling that you belong within the culture. When you stage a social group event, you help members connect with like-minded people and understand their place within the group.

Vulnerability: Coyle describes vulnerability as the ability to expose your personal weakness and ask for support. When a group collaborates against a shared struggle, members expose their weaknesses and learn to ask one another for help.

Purpose: Coyle describes purpose as the feeling that you’re part of the group for a reason. Creating a moment to clarify the meaning and impact of a group member’s presence reminds them why they contribute to the group’s cause.

1) Create a shared moment: The social reality of being together with a group of people working toward the same cause is essential to understanding the magnitude of the group’s impact.

(Shortform note: Researchers find that remote work contributes strongly to lower employee job satisfaction and motivation. Many employees attribute this to a lack of social contact (or shared moments): Without the opportunity to meaningfully collaborate and chat with colleagues or see the impact of their work on clients, the work experience becomes endless, disengaging flatness.)

2) Allow for voluntary struggle: People naturally create strong bonds when they are struggling together, but they need to have chosen to be part of it. People who are forced to take on extra work become resentful and disengaged, whereas those who choose to struggle will have a genuine connection to the work and to others who do the extra work for the same reasons.

(Shortform note: Shared struggle is a powerful bonding tool—the Heaths discuss how it might bring together people who are already part of the same group, but studies have shown that pain or struggle enhances bonding in groups of people without any shared identity. Part of the reason for this is that struggle naturally forces group members to ask for help and show vulnerability, which is a foundational element of relationship-building.)

3) Reconnect with work’s meaning: Group members need to know that their work is much larger than themselves—you have to cultivate a group’s sense of purpose by showing them the impact of their work. Purpose is what allows people to see beyond their mundane or difficult individual tasks and feel a significant connection to the larger mission.

(Shortform note: Many organizations try to cultivate their employees’ passion instead of their purpose, but passion is a poor motivator that has caused a recent decline in workplace satisfaction: Studies cited in Cal Newport’s So Good They Can’t Ignore You show that only 45% of Americans report being happy with their jobs, likely because they feel that they should be doing something that aligns with their passions.)

Part 2: Use Connection to Deepen Individual Relationships

The Heaths explain that, contrary to what you might think, relationships do not naturally deepen or grow stronger over time. Without regular maintenance, relationships easily plateau—they won’t develop any further without a bit of engineering. A properly maintained relationship has positive peaks that serve as the defining moments that deepen the relationship.

In relationships, these positive peaks happen in instances of responsiveness—engagement with someone else that makes it clear that you’re listening to and care about them. Responsiveness conveys three essential messages:

- Support: I actively support you and will help you get what you want or need.

- Understanding: I know what’s important to you and who you are.

- Respect: I respect who you are and your wants or needs.

Responsiveness in Personal Relationships

In personal relationships, responsiveness is part of a formula: vulnerability + responsiveness = intimacy. In practice, this formula looks fairly simple: You share something (vulnerability) and then wait to see if the other person shares something in return (responsiveness). By choosing to respond, they express respect, understanding, and support.

The Heaths stress that intimacy doesn’t come from either responsiveness or vulnerability alone—it’s crucial that there’s an exchange between the two. When completed, this simple exchange allows the relationship to progress and deepen instead of plateauing. Keep in mind that this exchange doesn’t happen naturally—someone needs to take the first step to start the cycle of vulnerability. If you want richer, deeper connections, you must either be willing to be open with others or recognize when others are opening up to you.

The Importance of Aligning Expression and Reception

The Heaths’ approach to responsiveness is somewhat one-size-fits-all: Someone expresses vulnerability, and by expressing vulnerability in exchange, you reveal that you see them, care about them, and understand them. A crucially important point that this approach misses is that not everyone gives and receives support, understanding, and respect the same way.

Gary Chapman’s The Five Love Languages is well-known for its lessons in determining what actions make you and those in your life feel seen and understood. The book focuses on the way we express love through five “languages'': acts of service, physical touch, words of affirmation, gifts, and quality time. Knowing someone’s love language means that when they open up to you, you can respond to their vulnerability in a way that aligns with the way they view understanding and care—thereby deepening your relationship.

For example, your friend reveals to you that she’s behind on a project at work and is worried she’ll be fired if she doesn’t get it done.

You reply with your love language, words of affirmation: You say, “That’s so stressful. You’re so organized, though—I know you can do it.” Rather than feeling understood, she feels that you’re just saying nice things as a way to brush off her concerns.

You reply with her love language, acts of service: You say, “That’s so stressful. How about I pick up your kids from school each afternoon and feed them at my place? That way you can stay late at work without worrying. Let me know if I can do anything else.” Your friend feels understood and deeply connected to you because you’ve shown that you care in a way that makes sense to her.

Conclusion: What Defining Moments Give Us

Looking for moments that you can enhance with elevation, pride, connection, or insight can multiply the rich experiences that make your life meaningful. Focusing on meaningful moments is a way to reconnect with what’s important to a well-lived life. Investment in these moments offers you the opportunity to re-engage with your life and fight against the everyday flatness that causes days, months, and years to speed by.

Shortform Introduction

In The Power of Moments, brothers Chip and Dan Heath examine what makes certain moments more special or memorable than others. They propose four elements—elevation, insight, pride, and connection—you can engineer into small, everyday moments to make them exceptional. These lessons are applicable in all areas of life: Make richer memories with your children, increase employee loyalty, and give clients an experience they’ll never forget.

About the Authors

Chip and Dan Heath are brothers and co-authors. Chip is a professor of organizational behavior at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Additionally, he’s worked with 530 startups, helping them refine their business strategies and missions. Dan is a senior fellow at the Duke University CASE center, where he works with social entrepreneurs, helping them broaden their impact and fight for social good.

Together, they’ve written four bestselling books: Made to Stick, Switch, Decisive, and The Power of Moments. Their writing is often compared to that of Malcolm Gladwell, writer of popular psychology books like Outliers and Blink: Like Gladwell, they bring the concepts they discuss to life with entertaining anecdotes. This accessible style has helped many readers connect with tricky ideas around business strategy and human behavior, garnering their books rave reviews around the world.

Connect with Chip and Dan:

The Book’s Publication

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Published in 2017, The Power of Moments is the Heath brothers’ fourth book. Due to the international success of their three previous books, The Power of Moments was highly anticipated and became an instant New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller.

The Book’s Context

The Heaths’ focus on making the most of present moments dovetails with an increasing interest in personal fulfillment and happiness, partly in reaction to our society’s obsession with busyness and the pressure to always be “on.” Tired of being buried in work and social media upkeep as life’s richest moments pass them by, people are increasingly working on turning their focus to engaging more fully with the present (or living mindfully) and accumulating experiences rather than material things.

While the book may appeal on a personal level to a preoccupation with living in the now, it also appeals on a professional level to organizations by suggesting ways that they can use memorable moments to retain both employees and clients:

- Not only are employees more highly educated than ever before, but they also have access to websites that contain thousands of job listings, salary comparisons, and company ratings by insider employees. They can keep a constant eye out for a better offer or an environment where their skills and expertise may be better appreciated. As a result, employers must think about ways to retain employees and make their company stand out.

- The rise of online shopping means that consumers aren’t restricted to purchasing what’s nearby or most convenient. Consumers have near-endless options when it comes to choosing services or products, organizations must find ways to continually stand out against the competition.

When employees and clients have unlimited choice, organizations must step up and continually create special, memorable experiences that boost satisfaction and loyalty.

The Book’s Strengths and Weaknesses

Critical Reception

Reviews for The Power of Moments are generally positive. Many agree that the concepts of the book are accessible, eye-opening, and strikes a good balance in speaking to both the professional and personal experience.

Positive reviewers also commend the book for approaching the self-help genre from a new angle—instead of handing out tired clichés or directing readers to make major changes to their lives, the Heaths push readers to reflect on and recognize the life-enriching opportunities they already have. Finally, reviewers like that the Heaths don’t exclusively examine success and why things work—they take care to explore failures and explain why things don’t work.

On the other hand, Publishers Weekly and other negative reviews bring up several points of criticism. First, they suggest that the book’s principles and suggested actions skew too much toward corporations and the ways organizations might use memorable moments to increase client or employee satisfaction and loyalty, rather than discussing ways that individuals or families can apply the principles to their personal lives.

Second, the Heaths seem to gloss over a glaring question: When you’re engineering special, meaningful moments, can they ever truly feel genuine? To some, the Heaths’ process of analyzing data and pinpointing patterns seems far too rational for real, lived moments.

Commentary on the Book’s Approach

As mentioned, the Heaths express their ideas in an approachable way, weaving together research and suggested applications of their ideas with entertaining case studies and anecdotes.

For the most part, they discuss both successful and unsuccessful types of moments in an attempt to convey why the actions they discuss are critical. Additionally, they attempt to strike a balance between professional and personal examples and applications of their ideas (but, as reviewers suggest, the book seems to skew more toward professionals.)

Commentary on the Book’s Organization

The Heaths start with a discussion of memory, exploring some of the psychological phenomena behind why we remember the things that we do. From there, they build into a discussion of “defining moments”: Memorable and meaningful moments that can be engineered by adding positive, memorable events to experiences such as transitions, milestones, and negative situations. Throughout the rest of the book, they discuss four elements that you can add to these experiences in order to make them defining:

- Elevation

- Insight

- Pride

- Connection

(Note: The Heaths flip-flop between calling elevation, insight, pride, and connection “elements” of defining moments and “types” of defining moments. We’ve chosen to use “elements” throughout—both for consistency and to underscore the Heaths’ point that everyday, forgettable moments become memorable when enhanced with certain elements.)

Our Approach in This Guide

We’ve extended the authors’ ideas to fill the gaps that reviewers’ two main criticisms highlight—that the book caters too much to a corporate audience and doesn’t explain how engineered moments can be genuine.

To address the first critique, we’ve introduced more examples that better demonstrate how the Heaths’ principles work in both professional and personal settings.

To address the second critique, we’ve reorganized some of the book’s content and added commentary to better explain the psychology behind memorable moments and clarify how the impact of defining moments can be genuine, even if the moment itself is staged.

A weakness in the Heaths’ organization is that they only discuss the power of novelty or surprise in moments that use the element of elevation. However, novelty or surprise is an essential addition to all four elements because unexpectedness is what makes certain moments stand out in your memory. Consequently, we’ve moved the discussion of novelty and unexpectedness to the first chapter on the psychology of memory, in order to include it in our core understanding of what makes a moment both meaningful and memorable.

Finally, the Heaths occasionally focus on the successes of their selected case studies without fully discussing the underlying circumstances or psychological phenomena that contributed to the moment’s success. In these instances, we’ve added commentary to fully explore reasons for the success of the Heaths’ chosen case studies.

Chapter 1: The Psychology Behind Memory

Large, important moments of your life—such as your wedding or the birth of your first child—naturally stand out in your memory. What’s less obvious is that with a bit of thought and effort, you can engineer small, everyday moments to stand out in your memory just as much as these big moments.

These small, memorable experiences are called defining moments because they have the potential to change the way you think, shape your perceptions of an experience, or establish new connections.

Two Psychological Phenomena That Form Defining Moments

Before trying to engineer memorable moments, it’s important to understand how memory works. There are two psychological phenomena that determine which experiences tend to stand out in your memory.

1) The Peak-End Rule

It’s obvious why some events—like marriage, or having kids—would stand out on the timeline of your life. But what about smaller, simpler moments such as a particular family vacation or an outing with a friend?

Typically, the way you recall special memories is shaped by the “peak-end rule,” proposed by psychologists Barbara Frederickson and Daniel Kahneman (author of Thinking, Fast and Slow). The peak-end rule states that when people reflect on an experience, they tend to ignore the duration of the experience. Instead, they focus on two key parts:

- The emotional peaks—the moments of strongest positive or negative emotion

- The end of the experience.

Imagine you spend a day at the beach with your kids. The drive is long, and it’s cloudy when you arrive. As you set up your umbrella and blanket, the sun finally peeks out. Around lunchtime, your kids are delighted to see a pod of dolphins playing just offshore. By the end of the day, everyone is exhausted, sunburned, and a little cranky. You pack up just before dark and spot an ice cream truck on the walk to the car, so everyone ends the day snacking on their favorite ice cream.

If you were asked about your day right after finishing your ice cream, you’d reflect on all the events of the day and chalk it up to a fairly average experience. However, if you were approached several weeks later and asked to reflect on the day, you’d likely give it a rave review. This is because, according to the peak-end rule, the parts of the day that will stand out in your memory are seeing dolphins (the peak) and eating your favorite ice cream with your kids (the end). All the other parts of the day—the cloudy sky, the sunburn, the long drive—fade into the background of these two positive experiences.

Our Terminology in This Guide

Throughout the book, the Heaths use “peak” to mean positive defining moments. In contrast, Kahneman uses “peak” to mean an experience’s most intense emotions—positive or negative.

To avoid confusion between these multiple meanings—while preserving the Heaths’ useful visual of “peaks” and “pits” against the “flatness” of everyday life—we’ll use the following terminology:

Emotional highs (the Heaths’ “peaks” and Kahneman’s “positive emotional peak”) will be referred to as positive peaks.

Emotional lows (the Heaths’ “pits” and Kahneman’s “negative emotional peak”) will be referred to as negative pits.

Longer Timelines Warp the Peak-End Rule

Kahneman’s research shows that the peak-end rule holds when an experience is relatively short and has a definite beginning and end—a day at the beach or a week of camping, for example. However, the Heaths explain that when it comes to recalling long-term experiences, the peak-end rule changes.

Peak: Peaks retain their importance—that is, one or two exceptional moments can make a mundane experience stand out in your memory as wholly amazing.

- For example, you start a new job. Your company sets up an incredible orientation program, and in your seventh month you receive the sales team’s “MVP Award.” Looking back on this first year, you might report it as a great experience, though most of your time was spent on meetings, dull tasks, or filing paperwork. The mundane day-to-day events fade into the background of several exceptional events.

End: On the other hand, endings tend to lose their importance and blur with beginnings. When you left college and headed into your first job, it was both an ending and a beginning. When it comes to long-term experiences, it makes more sense to think in terms of transitions rather than beginnings and endings.

This builds to the Heaths’ main point: When you think back on your life, you won’t recall every moment, nor will you consider your life’s “average” happiness. Your memory will naturally highlight positive peaks and transitional experiences.

Your Experiencing Self Versus Your Remembering Self

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman underscores the benefits of focusing on the creation of exceptional moments in the present. His research reveals that we have two “selves”:

The experiencing self, who feels the moment-to-moment emotions of an experience—their evaluation of the experience is a sum of the emotions they felt.

The remembering self, who reflects on past experiences—their evaluation of the experience depends on the peak-end rule (that is, they base their evaluation on the most emotionally intense moments and the end.)

You tend to naturally give more weight to your remembering self because you make most of your decisions based on your memory of an event. Kahneman, however, suggests that you can have more pleasure by consciously giving more weight to your experiencing self, spending more time creating moment-to-moment happiness. The Heaths’ creation of defining moments that increase our day-to-day happiness and engagement aligns with this argument.

2) Novelty or Unexpectedness

A second reason defining moments stand out is that your brain responds more actively to novelty than it does to routine. Imagine you were watching identical images of a dolphin flash across a screen, every image appearing for exactly two seconds. Suddenly, in the middle of all these dolphins, a photo of a red backpack flashes across the screen for exactly two seconds. A psychological study has found that, if you were to report afterward how long each image stayed on the screen, you would claim that the red backpack was on the screen for significantly more time than the identical dolphins, even though every image was shown for two seconds.

This happens because after seeing the same image multiple times, your brain doesn’t need to process any more information about it and “checks out.” When the new image suddenly appears, your brain re-engages. It processes a lot of new information in the same amount of time it was previously processing no new information—this tricks you into thinking you were seeing the image for a longer period of time.

The Reminiscence Bump

The way the brain responds to novelty reveals a key idea about memory and the importance of creating defining moments. If you were to reflect on your life and name the most memorable events, it’s likely that most of the named events occurred in your late adolescence and early adulthood. This is called the “reminiscence bump,” and it happens because you experienced many “firsts” between the ages of 15 and 30, such as your first kiss, your first job, or your first apartment. Because of the inherent novelty of these firsts, they stand out in your memory. However, after about age 30, your “firsts” naturally reduce and there are fewer opportunities to experience novelty—the flat routine of everyday life takes over and your brain, seeing the same “image” again and again, disengages. This is why time seems to speed up as you get older.

By creating experiences of novelty or unexpectedness, you create “red backpacks” that stand out against the monotonous “dolphins” of your life. They re-engage your brain and force you to process new information—not only does this allow you to more fully experience and enjoy moments and create richer memories, but it also makes you feel that time is passing more slowly.

(Shortform note: Our brains are hardwired to respond to novelty because this trait had a large part in our evolution and survival. The survival of biological species depends on being able to detect novel, and possibly threatening, additions to their environment. Following Darwin’s survival of the fittest theory, humans whose brains had a strong response to novel stimuli were able to respond more quickly to attacks or natural disasters and therefore survive, whereas those with a weak response to novelty were more likely to be caught off guard and die off.)

What Does This Mean for Defining Moments?

So far, the Heaths have explained that increasing the number of defining moments in your life means that you have more positive memories to look back on and a more present, slowed-down engagement with your life.

Before they get into different methods of creating such moments, the Heaths discuss two foundational aspects of defining moments: they’re both meaningful and memorable.

What Makes a Moment Meaningful?

To engineer meaning, the Heaths say your moment should incorporate at least one of four emotion-boosting elements:

- Elevation: The moment is elevated beyond everyday experience, either through sensory pleasures or the element of surprise.

- Insight: The moment helps you discover something new about the world or yourself. Often, these moments have a transformative and influential effect on the course of your life.

- Pride: The moment gives you a sense of validation around your achievements or a sense of pride in your actions.

- Connection: The moment makes you feel more deeply connected to whomever shares it with you, and strengthens your relationship with them.

The Heaths emphasize that a defining moment doesn’t need to use all four of these emotion-boosters—just one or two will do.

Shortform Commentary: Where These Four Elements Come From

The Heaths don’t note the exact research that led them to these four elements, but their ideas align closely with those of psychologist Abraham Maslow. Maslow is well-known for his “hierarchy of needs”:

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs describes the requirements for a person to become self-actualizing—constantly growing, discovering, and finding meaning in her life. The Heaths’ four elements align with Maslow’s three “higher needs” of self-actualization, esteem, and belonging:

- Elevation: Maslow notes, in Toward a Psychology of Being, that self-actualizing people are capable of experiencing “transcendent” moments, or moments elevated above the everyday experience that create a sense of delight, wonder, surprise, and so on.

- Insight: Insight is the core of the self-actualization tier of the hierarchy. As we’ll discuss in Chapters 5-6, insight leads to personal growth, discovery, and a realization of your abilities and potential.

- Pride: Pride is the core of the esteem tier of the hierarchy. As we’ll discuss in Chapters 7-9, pride helps you feel more moments of achievement, feel respected, and act as your best self—all of which increase your sense of self-worth.

- Connection: Connection is the core of the belonging tier of the hierarchy. As we’ll discuss in Chapters 10-12, connection can strengthen your bonds within groups or deepen your personal relationships.

In short, elevation, insight, pride, and connection are the elements that allow humans to live, not simply survive.

What Makes a Moment Memorable?

While the Heaths discuss what makes a moment meaningful, they don’t delve into what makes it memorable, which is the second characteristic of a defining moment. In order to be memorable, most defining moments should have an aspect of novelty or unexpectedness.

Novelty, as we’ve discussed, makes moments stand out against the generally predictable landscape of life. Unexpectedness is important because when you experience emotions experienced in a moment of surprise, you experience them more intensely than you would in an “everyday” situation.

- For instance, the joy of spending time with your friends isn’t as intense as the joy of being surprised with a puppy for your birthday.

These high-intensity emotions send a signal to your brain that something important is happening—your brain responds by paying more attention than usual to the event at hand, while blocking out unrelated, external stimuli.

In the following chapter, we’ll explore how to pinpoint which moments could be made more meaningful and memorable.

Exercise: Reexamine Your Defining Moments

Defining moments are small, everyday events that are meaningful and memorable. Looking back at your own experiences is a good way to understand how small moments can stand out in your memory.

Think back on the past few months and pick out a small, everyday moment (like getting dinner with friends, taking a day trip with a spouse, or spending time with your kids) that was meaningful to you. Describe the event.

Now examine your answer to the above question. What were the positive peaks of the experience? How did the experience end?

How do you think the peak-end rule contributed to your overall memory of this event?

Chapter 2: How to See the Potential for Defining Moments

There’s a common misconception that defining moments are large milestone events—such as the birth of your child—or simply happen as a matter of pure serendipity—such as going to a café and bumping into the woman you’ll marry. However, the Heaths emphasize that most defining moments happen in small, everyday events, and what makes them stand out is how you shape them by investing your time, effort, and strategic thought.

(Shortform note: As we noted in our introduction, the publication of the Heaths’ book coincided with a growing trend of people trying to engage more mindfully with their lives. Their central argument that defining moments happen in small, special instances likely strikes a chord with people living mindfully because focusing on the significance of small moments is a central practice of mindfulness.)

Investing in these moments allows you to build a richer life for yourself and others. By seizing on the potential of small experiences, you can create deeper connections with the people around you, increase brand loyalty among satisfied clients, have a memorable influence on your students or employees, and multiply the fulfilling experiences of your life.

In this chapter, we’ll look at three situations where opportunities to create defining moments often come up naturally.

Three Common Situations for Defining Moments

What we know about the psychology of memory suggests three naturally occurring situations with defining moment potential: transitions, milestones, and negative pits.

Situation 1: Transitions

Many large transitions, like your bar mitzvah or college graduation, are natural defining moments: They clearly mark a shift from one stage of your life to another in a memorable and meaningful way. However, many people don’t realize how many small transitions happen around us every day—many of which can be made just as memorable and meaningful as the large, obvious ones.

When everyday transitions aren’t marked off by a clear moment, they blend into the flat “sameness” of life, becoming forgettable and meaningless. In some cases, these unmarked transitions—and the lack of clear division between the way things were and the way things are—can cause anxiety. Transitions have the potential to become memorable and meaningful when you engineer a clear moment that carries you from one stage to the next.

Example: Moving On After a Pet’s Passing

After losing your beloved dog Rocky, you struggle to find a new dog to adopt. Eventually, you realize you’re still deeply attached to Rocky and are looking for an exact replacement for him so it feels like he never left.

To help you let go of this attachment, your partner sets up a small ceremony at Rocky’s favorite dog park. You set up a toy box filled with his old toys. Then, you affix a small plaque commemorating Rocky to the bench you two always shared—it helps you have a place where you can continue to feel close to him. After the ceremony, you start the paperwork to adopt a dog you visited a few weeks ago. The ceremony helped you mark the transition from your life with Rocky to your life with a new dog.

What Types of Transitions Need “Shape”?

Transitions often fall under four categories—expected, unexpected, unrealized, and gradual—and they can be large, emotional events or small, personal events. Added shape can be useful for any of these transition types.

Expected: These types of transitions are planned out and relatively predictable—often, they’re experiences that most people can relate to. For example, a personal, expected transition may happen when you change jobs and need to transition from an old way of thinking to a new way.

- For this experience, you can add shape by putting together a personal celebration or two when you make the transition between roles, as Michael D. Watkins suggests in The First 90 Days. You might purchase a new suit or organize a lunch with your new team members where you’ll talk about your new role and get to know them better.

Unexpected: These types of transitions happen at unpredictable times and often aren’t aligned with the experiences of those around you. For example, an emotional, unexpected transition may happen when you receive a diagnosis of a life-threatening illness.

- When Professor Randy Pausch received his terminal pancreatic cancer diagnosis, he added shape to the unexpected transition by creating The Last Lecture to talk about his life experiences and lessons. This lecture was a way to mark the end of his life, say goodbye to friends and colleagues, and give his family a lasting memoir of his love.

Unrealized: “Unrealized” transitions are those that we expect will happen, but ultimately don’t come to pass. An unrealized transition might look like expecting to graduate college and then dropping out, or expecting to get married but never doing so.

- You can add shape to these types of transitions by creating an event that gives closure—for example, you might stage an “undiploma ceremony” to close the college chapter of your life and become more fully engaged in the path your life has taken instead of ruminating on “what could have been.”

Gradual: The gradual transition refers to progress that happens slowly over time—the person going through a gradual transition often isn’t aware it’s happening. This can look like developing a friendship or learning a new skill. (We’ll explore ways to add shape to progress in Chapters 7-9.)

Situation 2: Milestones

Milestones are life events that are acknowledged and feel significant, but are largely arbitrary—for example, turning 30 doesn’t change your life in any significant way, but it feels like an important event all the same. Like transitions, bigger milestones—such as your 21st birthday, retirement, or the purchase of your first home—are more celebrated and therefore more memorable. However, you can easily make small, often-unnoticed milestones into memorable positive spikes with a bit of attention and effort.

How “Adulting” Helps Create Milestones

In The Defining Decade, Meg Jay urges young adults to seek out and celebrate milestones to develop their confidence and pride in themselves—factors that positively affect the way the rest of their lives play out.

One way we can see young adults, especially millennials, seeking out milestones to celebrate is in the way they’ve latched onto celebrating instances of “adulting,” or acting in an adult manner—for example, buying a car, doing their own taxes for the first time, or going shopping for a new couch.

Some people scoff at this practice of celebrating mundane, obligatory activities and label it another way for millennials to make themselves feel “special.” However, the Heaths’ ideas support young adults’ efforts to find meaning in these novel—though mundane—activities and see them as small milestones along their path to adulthood.

Example: Celebrating an Employee’s 100th Day

As an example of how to highlight an often-unnoticed milestone, imagine you’ve started a new job. After about three months of working there, you walk into your office to find your cubicle decorated with a banner that reads, “Happy 100 Days!” and a bowl of your favorite candy sitting on your desk. You check your work calendar and see that you have two hours blocked off for a “special lunch event,” during which the organization’s president takes you out for a nice lunch, and you spend a few hours getting to know each other. In the afternoon, your boss stops by to drop off a company “swag bag” that includes a nice jacket, water bottle, and mug branded with the company logo.

An employee’s 100th day working for a company has great potential to be a defining moment, but most organizations don’t think to invest in it and let the day pass by just like any other. If you spot the event’s potential and invest time and effort into making it special for the employee, you’ll create a defining moment that will stand out when they look back on their career with you and will increase their satisfaction and loyalty.

Situation 3: Negative Pits

Recall that negative pits are the emotional lows of an experience—without any intervention, these are the moments someone will remember about an experience when they reflect on it. The Heaths observe that most people react to a negative pit by trying to find a way to fix it and lessen the negative emotions of it. For example, clients hate being on hold, so many companies will play music or trivia to fill the wait time. By fixing the negative pit of being on hold with an entertaining distraction, these companies help ensure that the long wait time isn’t what the client recalls most vividly about her experience.

The Heaths explain that hard moments can actually become positive defining moments when you go beyond simply repairing them—and instead, find a way to turn them into positive peaks to look back on fondly. There are two ways you might do this:

1) Create an unexpected positive experience in response to the pit. Take the pet supply company Chewy as an example: If you inform them that your pet has passed away, they cancel your food delivery subscription immediately. This is the response you expect of them. However, they then go above and beyond expectation to fill in your negative pit with something positive—they send you flowers and a handwritten sympathy card signed by the Chewy team. In this way, they create a positive defining moment that will stand out in your memory when you recall your experience with their brand.

2) Put together a plan of action in response to the negative pit. The Heaths attest that the most memorable—but most uncommon—way to fix a negative pit is to make a perceptible effort to fix it. In many cases, acknowledging a problem, coming up with a plan, and demonstrating a willingness to make things right can make people think of the experience as overall positive.

- For example, a car rental company finds that they don’t get very high customer satisfaction ratings when everything goes perfectly. Rather, their highest ratings come from instances of booking mix-ups and car breakdowns because these situations allow them to demonstrate an effort to work with the client and remedy the problem as quickly as possible. Though something went wrong, the company’s response creates a positive defining moment for their client. Instead of recalling the negative moment, she recalls their swift plan of action and willingness to do everything possible to fix the mistake.

In their book, the Heaths largely focus on turning negative pits into positive peaks within the context of customer service or team member satisfaction, but this idea can apply to personal experiences with negative pits as well—such as receiving a daunting diagnosis or experiencing failure.

Turning negative pits into positive peaks in these personal experiences often isn’t obvious or doesn’t look “fun” as it does in customer service or employee loyalty contexts. Rather, it shows up in personal transformations, a deepening understanding of yourself and your values, and a newfound appreciation of your strength or abilities.

We examine this point further and explore ways to make negative pits into meaningful, memorable experiences in our discussion of self-insight in Chapters 5-6.

Remember That Investment-Worthy Opportunities Are Everywhere

The Heaths urge you to remember that, while many opportunities for defining moments naturally crop up during transitions, milestones, and negative pits, not all opportunities for defining moments fall neatly into these three categories. Look at all experiences as potential defining moments, because any moment can be made more meaningful and memorable with attention, forethought, and effort.

In other words, not many moments are “engineered” from the very beginning. Most important moments in your life unfold naturally and spontaneously—and these small moments are happening all around you, every day. It’s not engineering experiences from the beginning that’s important. What’s important is your ability to see the extraordinary potential of small, spontaneous moments and your willingness to put in the effort to build them into defining, meaningful moments that matter.

(Shortform note: Several negative reviews of The Power of Moments questioned whether defining moments can ever feel “real” if they’re so carefully engineered. This criticism misses a central idea of the Heaths’ argument—defining moments already exist and therefore are genuine. “Engineering” moments doesn’t mean staging a false event—it simply means giving attention and effort to important events that might otherwise go undetected.)

Exercise: Find Opportunities for Defining Moments

Practice recognizing the importance of adding shape to small transitions and celebrating unseen milestones.

Think of your organization, your career, your classroom, or your relationship. What is a transition or milestone that could be better recognized? (For example, your child reading their 25th book or your transition back to playing a sport after recovering from an injury.)

What can you do to mark the transition or celebrate the milestone? (For example, creating a dinner based on your child’s favorite book, or getting friends together for a 5k in costume to mark your first post-injury run.)

Are you encountering a negative pit—a moment of pain or anxiety—in your organization, career, classroom, or relationship? Describe the pit and how it might have been created.

What is your plan of action to turn the negative situation into a positive peak? How can you make a perceptible effort to improve the situation?

Chapters 3-4: Create Defining Moments With Elevation

Over the next four chapters, we’ll examine different ways to use the elements of elevation, insight, pride, and connection to turn everyday moments into unexpected, emotionally charged experiences that stand out against the flat background of life.

The first element we’ll discuss is elevation. Moments defined by elevation transcend everyday patterns and impart positive feelings like delight, motivation, and engagement. In short, elevated moments are the positive peaks that you look back on fondly.

(Shortform note: In his hierarchy, Maslow lists “peak experiences'' as a component of the highest need, self-actualization. Maslow described peak experiences as small, everyday events that give us a feeling of newness or delight—in other words, as with elevated moments, we transcend everyday dullness.)

Some of these positive peaks are naturally occurring in social moments like weddings and graduations, performance moments like playing in a big game or giving a talk in your field of expertise, and spontaneous moments like an unexpected upgrade on your flight. However, most experiences don’t have natural positive peaks—but you can add positive peaks to them by choosing one or two moments to elevate thoughtfully.

While elevating certain moments will take a bit of extra effort, they’re worth the trouble—their absence, an endless routine lacking “peakiness,” leads to boredom and disengagement.

- Think of a dull relationship that stretches on for years. Everything’s fine, but nothing new ever happens. Eventually, you both mentally check out and decide to call it quits. Or, you spend years working in a job where every week feels exactly the same—it feels soul-sucking, and you start looking for work elsewhere.

Using elevation to produce novel, memorable events is key to creating experiences that foster positive feelings and increase engagement. The Heaths’ identify three ways to use elevation: increase sensory pleasure, raise the stakes, and go off script with strategic surprise. Successful, memorable moments incorporate at least two of these methods.

Method 1: Increase Sensory Pleasure

The first way the Heaths suggest elevating a moment is with increased sensory pleasure—that is, making a moment look, feel, taste, or sound better than what you’re used to.

- For instance, getting dressed up to go out to a fancy restaurant looks, feels, and tastes different from eating in your sweatpants on the couch.

Sensory differences make memories stick. This is because a sensory upgrade is a type of novelty—it forces the brain to re-engage, process more information, and make the experience richer and more memorable.

The authors note that upping the sensory appeal of a moment doesn’t need to be expensive or extravagant—it can be as simple as a team leader conducting her employees’ year-end meetings in a park instead of in her office, or a rabbi delivering the Torah to a synagogue member’s home during the COVID-19 pandemic so that his bar mitzvah would physically feel special, even if it needed to be done by video.

Which Senses Should You Elevate?

The Heaths don’t discuss which sensory appeals work best, but numerous studies have concluded that memory links most strongly to your sense of smell. You can use this information to engineer small, special moments in a variety of contexts. For example:

You wear a certain “date night” perfume or cologne to make outings with your partner feel more special—and, each time you smell it, you’ll recall memories of past outings.

You bake a certain type of cookie every Friday afternoon with your kids to celebrate the coming weekend. The moment stands out against the rest of the week, and your kids will recall it every time they smell that type of cookie in the future.

Many organizations invest a lot of money in scent branding to evoke certain emotions in their clients, make clients feel that their products are high-quality, and ensure that their clients recall their brand whenever they encounter a certain scent.

Method 2: Heighten the Stakes

The second way to elevate a moment is to raise the stakes. The Heaths explain that adding high stakes to a situation makes an otherwise flat, unengaging experience into a standout, exciting experience—for instance when you look back at your high school career, you’ll more likely remember your debate team championship than your algebra classes.

(Shortform note: One reason that high-stakes experiences stand out in your memory may be that the prospect of a high reward forces your brain to use long-term memory to “help out” your short-term working memory. As a result, your attention is more fully focused on the event—your brain re-engages in order to process all the information you’re taking in.)

Raising the Stakes Effectively

Raising the stakes can seem like the same thing as increasing stress, but this line of thinking is a mistake. Stress not only has a strong negative impact on memory recall, but it’s also usually not particularly meaningful. High-stakes situations that aren’t enjoyable or rewarding in any way cause stress.

- For example, assigning your students an oral presentation that counts for 50% of their grade raises the stakes of an assignment by adding stress. The students won’t look back on the experience as a positive one—among the other stresses of their academic careers, it likely won’t stand out at all.

To raise the stakes effectively, focus on increasing productive pressure: Pressure that’s interesting or fun in some way. Most experiences during students’ academic careers are focused on grades—productive pressure shifts the focus in a novel direction, toward fun. Rather than blending into the everyday stress of school, a fun experience stands out in students’ memories for years to come.

- Let’s reimagine the oral presentation: You have each of your students choose a personal hero to interview. Instead of having each student give their presentation in the classroom like regular presentations, you organize a “Hero Day” in the auditorium. Each student’s interview subject is invited to come to the special event where they’ll listen to the speeches and mingle at an afterparty. Hero Day adds productive pressure to the presentation—with the added pressure of having their heroes listening in on their work, the students feel excitement in putting together a presentation that best represents someone they look up to.

Method 3: Go Off Script

The last method of elevating a moment is going off script, which the Heaths define as acting in a way that goes against what people expect. Of the three methods of elevation, going off script takes the most effort but is usually the most worthwhile: Recall our discussion of the “reminiscence bump”—the most memorable times of your life are due to going off script, encountering something unexpected and new as a result.

The idea that going off script takes extra effort may be confusing at first glance. It doesn’t seem so hard to come up with the occasional novel experience or fun surprise every now and then. The problem with this thinking is the assumption that you can meaningfully elevate an experience with cheap, easy surprises.

- For example, you bring cupcakes to your weekly HR team meeting on improving employee experience. It’s a nice gesture, but the surprise won’t be memorable or meaningful as long as the rest of the meeting unfolds the same exact way it always does.

Going off script in a way that’s meaningful and memorable requires strategic surprises.

(Shortform note: Cheap, easy surprises are almost-predictable events—having a snack at a meeting is overall, an unremarkable event. In contrast, strategic surprises are surprises that break behavioral patterns in a way that challenges assumptions about what comes next and draws the audience in.)

How to Create Strategic Surprise

The Heaths say that there are two steps to creating strategic surprise:

- Identify scripts, or patterns, in your life, such as how your team meetings are run or how you spend time with your spouse after work.

- Determine how you can go off these scripts in a meaningful way.

For example, you examine your weekly HR meeting’s script and decide to add a strategic surprise: Assigning each of your team members a “new hire” role and sending them out to interview their “new teams” with questions about advice for new team members and maintaining work/life balance. At the end of the hour, your team members meet up and discuss your new insights. By going off your regular meeting script, you’ve elevated the experience and created a defining moment for your team members.

Meaningfully going off script doesn’t mean completely upending the scripts of your life. Remember, memorable experiences are not wholly amazing—they’re largely mundane, with one or two exceptional peaks. Your goal, then, is to deliberately punctuate overall familiar and comfortable scripts with one or two delightful surprises. There are usually two types of scripts that you’ll deal with.

Script 1: One-Off Experiences

The Heaths say it’s relatively easy to elevate experiences in places that people visit only occasionally—a hotel, for example.

Imagine a hotel near an airport that caters to people coming in and out of the city for meetings. It’s not very interesting: The décor is bland, there aren’t any nearby attractions, and there isn’t even a pool. However, this one hotel consistently gets rave reviews from guests, because they leverage the power of delight.

When you check in, the receptionist asks you what your favorite drink is. You go to your room and soon get a visit from a smartly-dressed staff member, there to deliver your chosen drink—on the house. On top of the charming unexpectedness of the free drink, the moment certainly appeals to the senses: The staff member’s clothing makes the moment feel a bit fancy, and nothing compares to the first sip of a cool drink after a long day of meetings. This small moment becomes the positive peak that stands out against your mundane business trip and the underwhelming hotel—the moment that you remember as you write your review and tell others about your trip.

In one-off scripts, your goal is to go against what someone expects. The hotel’s free drink delivery stands out as a defining moment because it disrupts the client’s expectation—that the hotel staff will simply check them into their room with no special treatment.

(Shortform note: You can think of the one-off script like a fun fact that you use to make a good first impression when meeting someone new. It retains its delightful quality because they don’t hear you say it every day—you only use it once for the one-off experience of meeting.)

Script 2: Repetitive, Everyday Experiences

In contrast, creating moments of delight is a little more difficult in places that people visit regularly, like a café. Even delightful surprises lose their charm if you experience them every day. In cases like this, it’s critical to remember the “strategic” part of the surprise: You want to go off script, but be careful not to create a new script in the meantime.

- For example, imagine you owned a café that started a new Free Cookie Friday—for your regular clients, this would be a fun surprise for a week or two, and then it would become just another part of their coffee break script.