1-Page Summary

What if you could write so clearly that your reader could perfectly understand your main ideas within the first 30 seconds of reading your prose? In The Pyramid Principle, writing expert Barbara Minto claims this is possible. She argues that the secret to clear, effective writing is beginning with your conclusions. She envisions strong writing to be structured like a pyramid, with conclusions at the peak and supporting evidence branching out beneath.

Minto developed this writing approach while working for a management consulting firm. She noticed that many of her colleagues were producing unclear reports that failed to reflect the strength of their ideas. She discovered that their writing was unclear because their ideas weren’t logically organized. Workers around the world now use her method to improve the organization of their reports. However, Minto’s approach works for any type of nonfiction writing. You can use it to improve how you write everything from emails to essays.

We’ll begin this guide by exploring why people produce unclear writing and why it’s a problem. Then, we’ll turn to solutions by presenting Minto’s method, which we’ll call Pyramid Writing. Throughout our guide, we’ll compare Minto’s ideas to those of other writing experts, such as William Zinsser. We’ll also explore some of the brain science behind Minto’s ideas. Furthermore, we’ll supplement Minto’s strategies with additional actionable ideas, such as how to enhance your nonfiction writing using techniques from fiction writing and poetry.

The Problem: Unclear Writing

According to Minto, people often produce unclear writing that’s time-consuming and mentally taxing to read. We’ll begin this section by exploring people’s typical writing process. Then, we’ll examine people’s typical reading process. Finally, we’ll contrast these two processes to illustrate why our typical writing approach fails to meet readers’ needs.

The Typical Writing Process

Minto argues that most people brainstorm ideas while they write, resulting in conclusions-last writing: writing that ends in a conclusion. First, they brainstorm ideas by writing sentences. Next, they review their ideas and consider how they relate to each other. Finally, they summarize these relationships in a concluding sentence. Here’s an example of conclusions-last writing: “It was an achingly gorgeous fall day. I knew that winter was around the corner. I also knew that nothing on my to-do list was urgent. So I decided to spend my Monday afternoon strolling through my tree-lined neighborhood.”

(Shortform note: Minto claims that most people automatically produce conclusions-last writing, but whether or not this is true for you may depend on your cultural background. One expert on intercultural communication claims that everyone is capable of presenting information in a variety of orders, but every culture tends to prefer one order over the others. For instance, people from continental European cultures tend to present their conclusions last, whereas people from Anglo-Saxon cultures usually present their conclusions first.)

The Typical Reading Process

Whereas writers typically formulate conclusions after they generate ideas, Minto claims that readers naturally formulate conclusions while they read. Our brains are wired to automatically identify the logical relationships between ideas and develop conclusions that summarize those ideas. This process helps us remember information since it’s easier to recall a single conclusion than to remember the multiple separate points that support it.

(Shortform note: Research in psychology supports Minto’s claim that formulating conclusions about a group of ideas helps you retain information. According to psychologists, we naturally engage in chunking: a process in which we compile related information into a thematically related “chunk.” Chunking helps you hold information in your working memory (your brain’s system for temporarily storing information). As Barbara Oakley explains in A Mind for Numbers, chunking also helps you retain information over time: Your long-term memory also stores information in the form of chunks.)

Why Conclusions-Last Writing Overburdens Readers

Minto argues that conclusions-last writing overburdens readers in two ways: 1) It makes reading more effortful and time-consuming, and 2) it confuses them. Let’s explore these two problems further, then illustrate them with an example.

Problem 1: Conclusions-Last Writing Makes Reading More Effortful

First, Minto argues that conclusions-last writing requires readers to expend time and energy forming conclusions as they read. When a writer doesn’t supply a conclusion up front, the reader defaults to their natural tendency of generating a conclusion themselves. This is a higher-order thinking skill that requires mental energy and slows down the reading process.

(Shortform note: Research supports Minto’s idea that it’s mentally taxing for readers to formulate their own conclusions. To formulate your own conclusions about a set of information, you engage in synthesis, a complex thinking process. When you synthesize, you summarize the information you read and use it to construct new meaning. Synthesis is a more complex and cognitively demanding thinking process compared to comprehension, which simply involves understanding information. A reader who encounters a conclusion at the beginning of a written piece can focus on comprehending the author’s conclusions, whereas a reader engaging with conclusions-last writing must expend mental energy synthesizing the author’s conclusions.)

Problem 2: Conclusions-Last Writing Creates Confusion

Second, according to Minto, conclusions-last writing can confuse readers. The conclusion that the reader forms as they read may differ from the author’s conclusion. When the reader finally encounters the author’s conclusion and notices it’s different from their own, they’ll likely become confused.

(Shortform note: Although Minto implies that you should avoid confusing your readers, research reveals that in some circumstances, confusion can actually improve people’s learning. When something you’re learning makes you confused, you become motivated to relieve that confusion. This motivation can deepen your engagement with the content and improve your memory of it. However, confusion only promotes learning and retention when learners have the skills and time to persist through that confusion. For instance, a reader with strong reading skills and the time to re-read may benefit from the confusion of conclusions-last writing. By contrast, someone with weaker reading skills or less time to re-read may not benefit from confusion.)

Example: A Conclusions-Last Opinion Piece

Let’s illustrate these two problems by considering this example of writing: “My workplace hosts a monthly, mandatory community-building lunch for employees. Some people arrive in high spirits because these lunches help them feel connected to others. Others arrive grumpy and stressed because they believe these lunches cut into their valuable work time.” (Note: This example omits the conclusion entirely.)

Most readers will automatically expend mental energy and time trying to find the similarities among these three sentences and summarize them into a conclusion. For instance, a reader might form this conclusion: “The writer is upset that some of their coworkers bring a negative attitude to work lunches.” Contrast this with the writer’s actual conclusion: “Some workplaces’ efforts to reduce employee burnout backfire when they make community-building activities mandatory.” Because the writer didn’t express this conclusion at the start of their paragraph, the reader interpreted the paragraph in a different way than the author intended. This lack of clarity could leave the reader feeling confused.

The Solution: Pyramid Writing

According to Minto, Pyramid Writing solves the problem of unclear writing by ensuring that you express your conclusions first. We’ll begin this section by explaining the main elements of the pyramid that gives this approach its name. Next, we’ll describe what it’s like to read Pyramid writing. Finally, we’ll explore what it’s like to write it.

The Elements of the Conclusions-First Pyramid

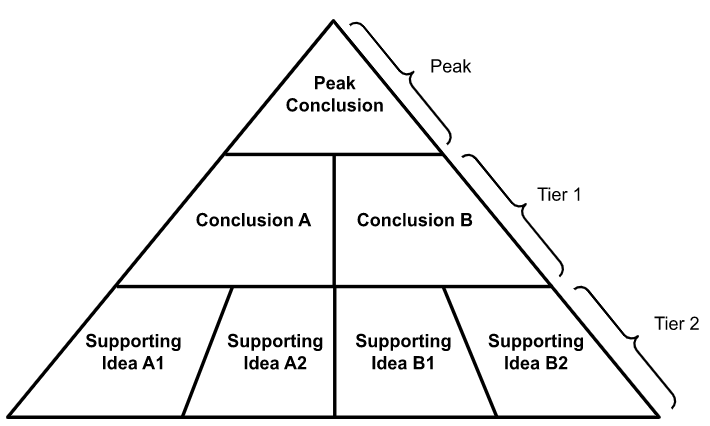

Let’s explore Minto’s pyramid structure, which we’ll call the Conclusions-First Pyramid. Here, we’ll visualize this pyramid and explain each of its labeled elements:

- The Peak: The top of the pyramid, which we call the Peak, represents the beginning of your written piece. This is where you present your piece’s main conclusion, which we’ll call the Peak Conclusion.

- Tier 1: After your Peak Conclusion comes the ideas it summarizes—the ideas that support it. These supporting ideas are the “bricks” that hold up the Peak Conclusion. We’ll call the row these supporting ideas occupy Tier 1.

(Shortform note: Minto isn’t the first writing expert to model their writing after a pyramid: Since the early 20th century, journalists have been structuring their writing using an inverted pyramid model (one that’s wide at the top and pointed at the bottom). Like Minto’s model for Pyramid Writing, this inverted pyramid has writers begin their pieces with the most important ideas. In this model, the wide base of the pyramid represents the beginning of a news story, where you share the most important takeaways. Less important information comes next: This is represented by the narrowing of the pyramid.)

Let’s explore how the structure of your Conclusions-First Pyramid may vary depending on the length and complexity of the piece you’re writing.

Structure 1: A Two-Tier Pyramid

Minto explains that you can plan out brief, simple pieces of writing using a pyramid with only two tiers. For example, the earlier piece about employee burnout needs only two tiers: an opening sentence that shares the Peak Conclusion, followed by a pair of Tier 1 sentences that share examples supporting that conclusion.

(Shortform note: What are some ideal scenarios for using a two-tier pyramid to structure your writing? You might think of the two-tier pyramid as a model for any paragraph that fits within a larger piece of writing. The conclusion would form the paragraph’s first sentence, and the supporting ideas would follow. Other simple forms of writing that you could structure using a two-tier pyramid include comments on online videos and social media posts, descriptions of items you’re selling online, and letters.)

Structure 2: A Three-Tier Pyramid

By contrast, Minto claims that multi-page pieces of writing (such as reports or books) need a pyramid with more than two tiers. Longer, more complex pieces of writing require that you also support the ideas in Tier 1. To accomplish this, add another tier below Tier 1. As shown below, when you add this new tier (which we’ll call Tier 2), the ideas in Tier 1 become conclusions for Tier 2’s supporting ideas.

For example, imagine you’re writing a two-page report. You begin the report with an introduction paragraph in which you share your Peak Conclusion and preview your Tier 1 conclusions that support the main conclusion. Then, you divide the rest of your piece into two sections: one for Conclusion A and another for Conclusion B. Each section features two paragraphs: one for each idea that supports the Tier 1 conclusions. These paragraphs form Tier 2.

(Shortform note: Although Minto doesn’t explain this explicitly, the structure she proposes for multi-paragraph pieces of writing features pyramids within a pyramid. Your entire piece forms a large pyramid topped with a conclusion that summarizes all the piece’s ideas. Within this large pyramid are smaller pyramids: Tier 1 conclusions with supporting evidence branching out beneath them. For instance, the diagram above includes three pyramid structures: a large pyramid topped by the Peak Conclusion, a second pyramid topped by Conclusion A, and a third pyramid topped by Conclusion B. Adding another tier below Tier 2 would create an additional set of smaller pyramids.)

Next, let’s explore why structuring your writing using a Conclusions-First Pyramid improves your reader’s experience.

The Reader’s Experience of Pyramid Writing

Minto argues that the structure of Pyramid Writing meets your reader’s need for logical clarity. Because you begin your writing by sharing your Peak Conclusion, your reader won’t have to form conclusions as they read. Instead, they can focus on fully understanding your ideas. By the time they reach the end of your piece, they’ll have a clear understanding of your ideas and overall argument.

(Shortform note: Because Pyramid Writing meets readers’ need for logical clarity, this type of writing may also free up your reader’s mind to engage more deeply with your ideas. In How to Read a Book, Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren claim that when readers aren’t focused on simply comprehending the text, they can engage in more sophisticated types of reading. One type of sophisticated reading is analytical reading: when you thoroughly understand an author’s ideas and critique those ideas.)

Next, let’s examine what it’s like to create Pyramid Writing.

The Writer’s Experience of Pyramid Writing

Minto explains that Pyramid Writing has you brainstorm and organize your ideas before you write them. As you generate new ideas during the brainstorming stage, you deposit them into the Conclusions-First Pyramid. Then, when it comes time to write, your ideas are already organized in a conclusions-first structure.

(Shortform note: Research supports Minto’s claim that it’s beneficial to brainstorm and organize your ideas before you write. Writers who take time to generate ideas and plan their structure before writing produce more organized final pieces. Furthermore, this process makes writing less mentally taxing. Experts theorize that brainstorming your ideas in advance reduces the strain on your working memory (your brain’s system for temporarily storing information) because it separates idea generation and organizing from the act of writing. If you try to generate, organize, and write ideas at the same time, your working memory—which has limited capacity—may become overloaded.)

In the following sections, we’ll break down the steps of using this pyramid structure to improve your writing process and its final outcome. To reflect Minto’s claim that you should separate brainstorming from writing, we’ve broken her process into these two stages.

Stage 1: Brainstorm

In this section, we’ll describe two steps for brainstorming your ideas: clarifying your topic and filling out the Conclusions-First Pyramid. We’ll illustrate these two steps using this one example: Imagine you’re sending an email to your neighborhood mailing list about your city’s upcoming composting program.

Step 1: Clarify Your Purpose

According to Minto, before you fill out your pyramid, you must clarify your purpose: what you want your piece to teach your readers. Minto claims that all readers are motivated to read so that they learn something new. To ensure you’ll fulfill this motivation, brainstorm answers to these two questions:

Question 1: What main question would your readers have about your topic? For example, if your topic is your city’s new composting program, your neighbors might wonder, “Should I compost?”

(Shortform note: Before determining your question, it may be helpful to pinpoint who your audience is and why they’re reading your piece. Briar Goldberg, the director of speaker coaching at TED, argues that public speakers should try to align their message with their audience’s goals. This makes it more likely that they’ll find your speech useful and memorable. You can apply this same idea to your writing, as well. While brainstorming your question, follow this advice from Goldberg: Consider who your audience is, why they’re taking time to pay attention to your ideas, and what they’ll likely want to gain from your ideas.)

Question 2: What’s your answer to your reader’s question? This answer will be your Peak Conclusion. For instance, your answer to the question “Should I compost?” might be “You should compost.” However, Minto points out that you may not always know your answer this early in the brainstorming process. In this case, skip brainstorming your answer—you’ll formulate it in the next step.

(Shortform note: How can you generate a strong, compelling answer to your reader’s question? In Get to the Point!, communication expert Joel Schwartzberg argues that a strong point (or in this case, a strong Peak Conclusion) meets these two criteria: 1) It’s an idea someone might disagree with, and 2) it requires analysis to explain. A conclusion that meets these criteria goes beyond what’s obvious, which justifies the existence of your written piece. For instance, the conclusion that you should compost meets Schwartzberg’s first criterion because someone could form a reasonable argument about why you shouldn't compost. Furthermore, this conclusion meets Schwartzberg’s second criterion because you must include analysis to thoroughly explain why you should compost.)

Step 2: Fill Out the Conclusions-First Pyramid

After you clarify your purpose, your next step is to use the Conclusions-First Pyramid to structure your ideas. According to Minto, there are two approaches to filling out the pyramid: a peak-to-base approach and a base-to-peak approach. The first approach has you fill out the pyramid from the top down. Minto recommends using the peak-to-base approach if you’ve already formulated an answer (the Peak Conclusion). By contrast, the base-to-peak approach has you fill out the pyramid from the bottom up. Use this approach if you haven’t yet brainstormed a Peak Conclusion or if the peak-to-base approach didn’t work for you.

(Shortform note: Although Minto presents a peak-to-base approach and a base-to-peak approach as a choice between two options, one expert on writing argues that you might use both approaches if your writing piece involves research (for instance, if you’re writing an opinion piece). In this case, you might begin by using an approach similar to Minto’s peak-to-base approach: You generate a main conclusion, then you develop details to support it. However, while conducting research to find these supporting ideas, you may discover that your original conclusion no longer matches the evidence. To remedy this, use a base-to-peak approach: Revise your Peak Conclusion to reflect what your researched evidence reveals.)

Here, we’ll further explain how to use each approach.

Approach 1: The Peak-to-Base Approach

Minto claims that when you already have your Peak Conclusion in mind, you can generate your remaining ideas by imagining you’re having a dialogue with a skeptical reader: someone who asks follow-up questions about each idea in your pyramid, starting at the peak. Your answers to their questions about the Peak Conclusion will become your Tier 1 ideas. If they continue to have questions about your Tier 1 ideas, you’ll answer those questions in Tier 2. Continue this process of adding tiers to your pyramid until you answer all of the skeptical reader’s questions.

For example, imagine a skeptical reader encounters your Peak Conclusion for the composting email: “You should compost.” They’ll most likely wonder, “Why?” The diagram below illustrates how your answers to this question form the conclusions in Tier 1. A skeptical reader would likely continue to have questions about these Tier 1 ideas. You can find the answers to those questions in Tier 2.

(Shortform note: It might be easier to use Minto’s strategy of generating ideas through questions and answers if you enlist the help of someone to play the role of the skeptical reader. Brainstorming with someone else can help you generate more ideas and clarify your existing ideas. Find a friend, colleague, family member, or mentor who’s willing to be your skeptical reader and willing to have their voice recorded. Instead of imagining the question-and-answer dialogue with a reader, have that dialogue with the person who’s helping you. Later, listen to the audio recording and transcribe your ideas into the pyramid format.)

Approach 2: Base-to-Peak Approach

According to Minto, a base-to-peak approach is a strong alternative to the peak-to-base approach, especially if you’re having trouble formulating your Peak Conclusion and/or your Tier 1 conclusions. To use the base-to-peak approach, follow these four steps:

Step 1: List ideas that answer your audience’s question. For example, in response to the question, “Should I compost?”, generate two lists: one list with reasons why a reader should compost, and one list with reasons why they shouldn’t compost.

(Shortform note: List-making is a helpful technique for generating ideas, and many experts claim that you should prioritize generating a large quantity of ideas over generating only quality ideas. When quantity is your focus, your ideas flow freely and you’re more likely to generate original, thoughtful ideas. When quality is your focus, there’s a risk your inner critic will stifle your creativity and you’ll end up with fewer strong ideas in your list.)

Step 2: Group your ideas based on their similarities. For instance, imagine you generated these four reasons why your reader should compost:

- The city will convert your organic waste into compost you can use in your garden.

- You’ll be entered into a raffle for a gift card to the gardening store.

- Using compost in our garden will reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

- Composting will divert our organic waste from landfills.

The first and second ideas are both reasons why composting benefits the individual reader. The third and fourth ideas are both reasons why composting benefits the community.

(Shortform note: A variety of techniques can assist you with grouping your ideas. One technique, called mind mapping, involves writing ideas in circles and drawing lines to connect ideas that are thematically related. Another technique is to use a highlighter to color-code your list items based on the similarities they share.)

Step 3: Generate a conclusion for each group and insert them into your pyramid. For example, this conclusion summarizes the first group of ideas: “Composting benefits you.” The conclusion summarizes the second group of ideas: “Composting benefits the community.” Write these conclusions in Tier 1, and write the specific supporting ideas from Step 2 in the tier below these conclusions.

Step 4: Generate a Peak Conclusion from your group conclusions. For example, write “You should compost” at the top of your pyramid.

(Shortform note: In How to Take Smart Notes, Sönke Ahrens argues that a bottom-up (or base-to-peak) approach offers an advantage over a top-down (or peak-to-base) approach: It prevents you from activating your confirmation bias. This bias is the tendency to search for and favor information that supports your existing beliefs. According to Ahrens, when you’re using a top-down or peak-to-base approach that has you form a conclusion first, you’ll only look for supporting evidence that confirms your conclusion—which could be an issue if your conclusion is wrong. By contrast, when you use a bottom-up or base-to-peak approach that has you wait to form a conclusion, you’re more likely to consider a wider variety of evidence and viewpoints and reach a more accurate conclusion.)

Stage 2: Write

After you’ve brainstormed your ideas in a pyramid structure, the next stage of Pyramid Writing is converting those ideas into prose. In this section, we’ll share four goals for doing so. We call these “goals” rather than “steps” to emphasize that you can accomplish them in any order.

Goal 1: Write a Clear, Engaging Introduction

According to Minto, your piece should begin with a clear, engaging introduction so that your reader understands your conclusions within the first 30 seconds of reading. Minto argues that doing this is polite: By providing your readers with a brief preview of your piece, you’re giving them the information they need to determine whether they should keep reading. For instance, imagine someone reading your composting email already believes she should compost. Once she reads your introduction, she’ll realize within the first 30 seconds that you agree; and from there, she may decide there’s no use reading a piece she already agrees with.

(Shortform note: How much can someone read in 30 seconds? Researchers estimate that adults’ average silent reading rate (the rate for reading in their heads) is 238 words per minute. An introduction that someone can read in 30 seconds should be close to half of that length: about 120 words. Most five-sentence paragraphs are close to that length. To respect your reader’s time, aim to explain your conclusions within a paragraph like this.)

Furthermore, Minto argues that you can make your introduction engaging by structuring it like a fictional story. Fictional stories typically have three parts: a beginning that sets the scene, a middle that introduces a problem, and an ending that resolves the problem. According to Minto, this structure works well for nonfiction introductions as well because it smoothly eases your reader toward your Peak Conclusion.

(Shortform note: Minto’s recommendation to enhance your introduction with techniques from fiction can be extended to other areas of your nonfiction piece as well. For example, you might apply the fiction-writing technique of building suspense to the title of your nonfiction piece. Fiction writers create suspense by leaving information out of their writing. Doing so plants questions in the reader’s mind and leaves them eager to discover the answers—so, they read on. To create suspense in your nonfiction piece’s title, drop a hint that there’s a problem without revealing the entire problem. Many of the most-read news articles feature suspenseful headlines that hint at a problem, such as “This is Why Uma Thurman is Angry.”)

Let’s explore how to craft a fiction-inspired introduction that features a beginning, middle, and end.

Introduction Element 1: The Beginning

According to Minto, the beginning of your introduction provides the reader with context for your topic. She claims that people tend to be receptive to new ideas they might disagree with if you first provide them with a familiar context. To do this, provide a “where” and “when” that together establish a context that the reader will recognize and relate to. For example: “As you may have heard, our city is starting a new composting program next month.”

(Shortform note: How can you write a beginning sentence that establishes context and captures the reader’s attention? One writer recommends that you breathe life into your nonfiction writing by borrowing techniques from poetry. For instance, you can establish a context for an essay using a blazon: a list of descriptions that paint a picture of your “where” and “when.” Ta-Nehisi Coates’s well-known article “The Case for Reparations” provides an example of how to establish context with a blazon: “Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.”)

Introduction Element 2: The Middle

Minto explains that the introduction’s middle is where you share the question you brainstormed earlier (to which your Peak Conclusion is the answer or solution). The role of the middle is to pique your reader’s curiosity, compelling them to read on. You could phrase the middle as a question: “Should you compost?” Alternatively, you could phrase the middle as a problem: “I’ve heard many of you are unsure whether you should participate in the city’s composting program.”

(Shortform note: Research supports Minto’s claim that raising a question or problem compels your reader to continue reading. Psychologists claim that when we encounter an unfinished task in the form of a problem or question, we experience the Zeigarnik effect: We can’t stop thinking about that unfinished task, and we crave the relief of discovering how it resolves. Cliffhangers in books, movies, and TV use this effect to keep audiences hooked during breaks from the story.)

Introduction Element 3: The End

Finally, Minto claims that you should end your introduction by stating your Peak Conclusion and your Tier 1 conclusions. Sharing your Tier 1 conclusions provides the reader with a roadmap of what’s ahead, which improves the clarity of your piece. You can share your Peak Conclusion and Tier 1 conclusions in separate sentences, or you can combine them into a single sentence. This example does the latter: “I strongly encourage you to consider participating in the city’s composting program because it benefits both you and the community.”

(Shortform note: Starting your piece with context (in the form of the beginning and middle) before sharing your Peak Conclusion seems to contradict the premise of conclusions-first writing. However, we can infer from Minto’s recommendations for writing an introduction that your reader needs this context in order to comprehend your Peak Conclusion. Arguably, a piece of writing that begins with an introduction like this is still conclusions-first because you share the conclusions before you fully explore the Tier 1 ideas that support them.)

Goal 2: Order Ideas Logically

According to Minto, a second goal to work toward when writing is presenting your ideas in a logical order that reflects how they’re related. That way, your reader won’t have to expend mental energy or time determining how your ideas connect. First, decide which of your Tier 1 conclusions you’ll share first. Then, determine the order for each Tier 1 conclusion’s supporting ideas. Here are two options for how to order ideas:

Option 1: Action order. Share ideas in this order if one idea must happen before another, either because it must occur earlier in time or because it causes the idea that follows it. For instance, these three ideas are presented in action order: “The city will collect our organic waste, turn this waste into compost, and return the compost to us so we can garden with it.”

Option 2: Importance order. Alternatively, present your ideas in order of importance. Readers usually assume that ideas that come earlier in a sequence are more important.

(Shortform note: To help your readers follow the logical throughline of your ideas, consider using transition words and phrases. In On Writing Well, William Zinsser claims that transition words and phrases (such as “for example” and “finally”) show your reader how your ideas relate, which helps them follow your ideas’ logical order. If you’re expressing ideas in action order, use transition words such as “First” and “Next” to clarify that the ideas relate sequentially. For example: “First, the city will collect our organic waste. Then, they’ll turn this waste into compost. Finally, they’ll return the compost to us so we can garden with it.” If you’re expressing ideas in importance order, present the most crucial idea first and then use transition words such as “furthermore” and “additionally” to signal you’re moving on to another idea.)

Goal 3: Make Your Organization Clear to Your Reader

Third, Minto argues that your writing must signpost the pyramid structure you brainstormed so that it’s easy for readers to identify your conclusions and follow your logic. Here are three tips for making your organization clear to readers:

Tip 1: Use hierarchical headings. According to Minto, this style of signposting uses distinct heading styles for each level in your pyramid, signaling to your reader when you’re moving onto a conclusion’s supporting ideas. For example, you could use large, uppercase letters to indicate the title of your piece, medium-font text to title each of your Tier 1 conclusions, and small-font text to title each of the headings for your Tier 2 ideas.

Tip 2: Make your conclusions easy to spot. Minto claims that you can do this by bolding or italicizing sentences that contain your conclusions.

Tip 3: Use nesting. This involves indenting a piece of text to indicate that it supports the conclusion above it. Bullet points are a common form of nesting.

Clear Organization Also Aids Your Reader’s Memory

Hierarchical headings, easy-to-spot conclusions, and bullet points not only help your reader follow your ideas’ logical flow but also help your reader to remember your ideas. Let’s explore some research in psychology that suggests Minto’s strategies aid your reader’s memory.

Hierarchical headings: Researchers claim that headings help the reader build a mental representation of your piece’s organization. When readers think back on what they read, they conjure this mental representation and better recall the text’s ideas.

Easy-to-spot conclusions: One study on the psychology of font found that readers remember bolded ideas better than ideas that are italicized or presented in a normal style.

Nesting: Bullet points are a particularly useful form of nesting because they turn a set of ideas into a list. According to research, we remember information better when it’s in a list.

Goal 4: Craft a Motivating Ending

How do you end a conclusions-first piece of writing? Minto argues that you should end your piece with a new, motivating idea instead of simply restating your Peak Conclusion. A piece of Pyramid Writing doesn’t need a traditional concluding paragraph (in which you restate your main argument), since you’ve already shared your conclusions according to the conclusions-first approach. Instead, the best ending is one that presents a new idea: one that motivates your readers to either take your ideas seriously or take some sort of action. Let’s explore these two types of motivating endings.

Type 1: A Reminder of Your Ideas’ Significance

Minto claims that this type of ending provides context for why your ideas are important, which motivates readers to take your ideas seriously. For instance, imagine you’ve written a training manual for your employees. End your manual with these words: “Your day-to-day work—from contacting customers to filing receipts—keeps the business running and improves our customers’ lives.”

Type 2: A Call to Action

According to Minto, this type of ending motivates the reader to put your ideas into action. End with a call to action by sharing a specific action you’d like them to take and describing why it’s important. For example, imagine you’ve written an opinion piece to convince your readers to help formerly incarcerated people become voters. Your ending might be: “If you’re fed up with talking about change and are ready to spend time making change, join us at our meeting next week to learn how you can help ensure that eligible voters get to the polls by Election Day.”

When to Use Each Type of Ending

Minto doesn’t provide guidance on how to determine when to use each type of ending (or whether a neat ending is even necessary for your piece). To decide which type of ending best suits your writing, consider the piece’s purpose. Experts often claim that a piece of nonfiction writing usually has one of these three purposes: to inform, express, or persuade. Here, we’ll explore which of Minto’s ending strategies (if any) may work best for each purpose.

Informative writing: The purpose of informative writing is to educate the reader on a specific topic. Examples include news articles, reports, training manuals, meeting agendas, and meeting minutes. End informative writing with a reminder of your ideas’ significance so that people feel their time reading your piece was well spent. If your informative writing requires a response from your reader, end with a call to action that specifies what you need from them.

Expressive writing: The purpose of expressive writing is to reveal your opinion or share your experiences. Examples include personal essays, opinion articles, thank-you messages, and memoirs. Expressive writing may not need a concluding paragraph if it’s already chronological in nature (as in the case of a memoir). However, as with informative writing, it may be useful to end your expressive writing with a reminder of your ideas’ significance.

Persuasive writing: The purpose of persuasive writing is to convince someone to agree with your perspective. Examples include editorials, advertisements, political speeches, and cover letters. It’s effective to end persuasive writing with a call to action: This type of ending will indicate that your perspective is useful because it leads to action. Furthermore, a call to action brings about the change you want to see, bringing you the satisfaction that your writing has a purpose.

Exercise: Use the Pyramid Structure to Plan a Piece of Writing

In The Pyramid Principle, Minto claims that strong writers brainstorm and organize their ideas into a pyramid structure before they begin writing. Practice this now: Pick something to write, brainstorm your conclusions and supporting ideas, and draft your introduction.

Think about something you’ll need to write soon. It could be informative (such as a report summarizing your company’s progress), expressive (such as a thank-you letter to a friend), or persuasive (such as a message persuading your social media followers to contribute to a fundraiser). Then, describe your writing piece’s topic, question, and answer (or Peak Conclusion). (For example, your topic may be an upcoming fundraising effort for hurricane relief victims. A reader may wonder, “Why should I donate?” Your answer may be that their donation will save lives and restore victims’ hope.)

Now, use Minto’s top-down approach to generate ideas that support your Peak Conclusion. Start by imagining what question a skeptical reader would ask in response to your answer (your Peak Conclusion). Then, write your Tier 1 conclusions. (For instance, a skeptical reader may wonder, “How will my donation save lives and restore hope?” This could lead you to generate the following two conclusions: “Your donation will provide hurricane victims with emergency supplies such as medicine, food, and water” and “Your donation will provide hurricane victims with hope and reassurance that their community is here to support them.”)

Continue using this question-and-answer technique to generate your next row of supporting ideas. (For instance, a reader might wonder how their donation will provide medicine, food, and water to hurricane victims. You could explain which organizations will be using their donation and what type of relief each organization will provide for families.)

Finally, in the space below, draft an introduction that includes a beginning (which establishes the “where” and “when” of your topic), a middle (which raises the question or problem), and an end (which shares your Peak Conclusion and Tier 1 conclusions). (For example: “A local charity is raising funds to support hurricane survivors. Why should you donate? Because doing so will provide hope to those who’ve suffered great loss and save lives by providing food and water.”)