1-Page Summary

Thinking in Systems is an introduction to systems analysis. Many aspects of the world operate as complicated systems, rather than simple cause-effect relationships. Many problems in the world manifest from defects in how the systems work. Understanding how systems work, and how to intervene in them, is key to producing the changes you seek.

What Is a System?

A system is composed of three things:

- Elements: The individual things in the system

- Interconnections: The relationships between the elements

- Purpose or Function: What the system achieves

To define it more cohesively, a system is a set of elements that is interconnected in a way that achieves its function.

Many things in the world operate as systems.

- A football team consists of a group of players on the field, each with a specific role that interacts with the others. The larger team system also consists of coaches, support staff, and fans.

- Within the system of a corporation, people, machines, and information work together to achieve the corporation’s goals. This corporation then takes place within the larger system of the economy.

Stocks and Flows

Stocks and flows are the foundation of every system.

A stock represents the elements in a system that you can see, count or measure. It can be commonly thought of as an inventory, a store, or a backlog.

Flows are the means by which the stocks change over time. Inflows increase the level of stock, while outflows decrease the level of stock.

Let’s take a simple system: a bathtub.

- The stock is the amount of water in the tub.

- The inflow is water coming from the faucet into the tub. This raises the stock.

- The outflow is the drain that removes water from the tub. This decreases the stock.

This can be drawn on a stock-and-flow diagram, as here:

Many systems are analogous to the bathtub:

- In fossil fuels, the stock is the reservoir of fossil fuels. Mining lowers the stock, while natural processes increase the stock.

- The world population is a stock of people. The population grows with births and shrinks with deaths.

Properties of Stocks and Flows

Stocks take time to change. In a bathtub, think about how quick it is to change the inflow or outflow. It takes just a second to turn on the faucet. It takes minutes to fill the tub.

Why do stocks change so gradually? Because it takes time for the flows to flow. As a result, stocks change slowly. They act as buffers, delays, and lags. They are shock absorbers to the system.

From a human point of view, this has both benefits and drawbacks. On one hand, stocks represent stability. They let inflows and outflows go out of balance for a period of time.

- Your bank account stores money and gives your life stability. If you get fired from your job, the inflow of money will stop, but you can take money from your stock to continue living and figure out how to solve the problem.

On the other hand, a slowly-changing stock means things can’t change overnight.

- If a population’s skills become meaningless because of technology, you can’t re-educate the workforce instantaneously. It takes time for the information to work its way through the system and to flow to the population.

Where We Focus

As humans, when we look at systems, we tend to focus more on stocks than on flows. Furthermore, we tend to focus more on inflows than on outflows.

- When thinking about how the world population is growing, we naturally think about how increasing births must be driving the trend. We think less about how preventing death through better medical care also grows the population.

- Likewise, a company that wants to increase its headcount does so instinctively by hiring more people. It doesn’t often think as hard about how to reduce the outflow of people who quit or are fired.

This is just one example of how we, as simplicity-seeking humans, tend to ignore the complexity of systems and thus develop incomplete understandings of how to intervene.

Feedback Loops

Systems often produce behaviors that are persistent over time. In one type of case, the system seems self-correcting—stocks stay around a certain level. In another case, the system seems to spiral out of control—it either rockets up exponentially, or it shrinks very quickly.

When a behavior is persistent like this, it’s likely governed by a feedback loop. Loops form when changes in a stock affect the flows of the stock.

Balancing Feedback Loops (Stabilizing)

Also known as: negative feedback loops or self-regulation.

In balancing feedback loops, there is an acceptable setpoint of stock. If the stock changes relative to this acceptable level, the flows change to push it back to the acceptable level.

- If the stock dips below this level, the inflows increase and the outflows decrease, to increase the stock level.

- If the stock rises above the acceptable level, the inflows decrease and the outflows increase, to decrease the stock level.

An intuitive example is keeping a bathtub water level steady.

- If the level is too low, plug the drain and turn on the faucet.

- If the level is too high and the water spills out of the tub, open the drain and turn off the faucet.

Reinforcing Feedback Loops (Runaway)

Also known as: positive feedback loops, vicious cycles, virtuous cycles, flywheel effects, snowballing, compound growth, or exponential growth.

Reinforcing feedback loops have the opposite effect of balancing feedback loops—they amplify the change in stock and cause it to grow more quickly or shrink more quickly.

- As a stock level increases, the inflow also increases (or the outflow decreases), causing the stock level to further rise.

- In the other direction, as a stock level decreases, the inflow also decreases (or the outflow increases), causing the stock level to further decrease.

Here are examples of runaway loops in the positive direction:

- The more people there are in the world, the more they reproduce, which increases the stock of the world population.

- A healthy national economy grows in a reinforcing loop. In a nation, the more factories and people you have, the more you can produce. The more you produce, the more you can invest back in more factories and educating people.

Here are examples of runaway loops in the negative direction:

- In agriculture, plant roots help retain soil. The more that soil is eroded, the less roots can grow, which causes more erosion.

- In a natural emergency, a store may have a sale on its goods. The lower the stock of a good like toilet paper, the more fervently people want to buy it, which causes the stock to shrink further.

Building More Complicated Systems

From these basic building blocks, you can build up to more complicated systems that model the real world. In this 1-page summary, we’ll cover only one simple system and show how systems analysis can lead to an understanding of its behavior.

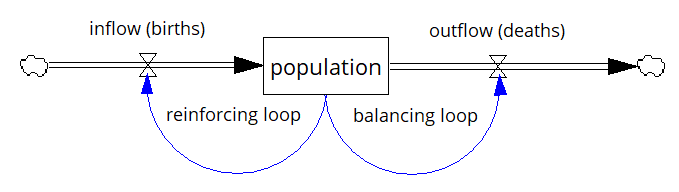

One Stock + One Reinforcing Loop, One Balancing Loop

We’ll look at a system with one stock and two loops that compete against each other—one reinforcing, and one balancing.

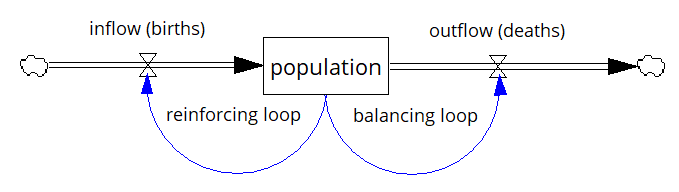

The concrete example we’ll use is the world population.

- The population is the stock.

- The reinforcing loop is birth rate—the more people there are, the more who reproduce. By itself, this leads to natural exponential growth.

- The balancing loop is deaths—the more people there are, the more who die. (Shortform note: In essence, the setpoint of this balancing loop is 0, and the further away from 0 the stock is, the more people who will die.)

The stock and flow diagram looks like this:

How does the population behave in this scenario? It depends on the relative strength of the two competing loops.

- If the birth rate is higher than the death rate, the population will grow exponentially. This is where the world overall currently is.

- If the death rate becomes larger than the birth rate, the population would shrink. (This can happen if the birth rate plummets, or the death rate skyrockets, or both.)

- If they are equal, the population will stay the same.

Different circumstances can drive the relative strength of the birth or death loop:

- Data suggests that as countries get wealthier, birth rates fall. Therefore, poorer countries with high current birth rates may not retain high birth rates as their economies develop.

- A lethal, contagious disease could drastically increase the death rate. For instance, during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, projections of populations in areas with high HIV prevalence had to account for higher mortality.

- Birth rate could also fall due to social factors, such as lower interest in raising children or fertility issues.

More Complicated Systems

Read the full summary to learn how:

- One stock + two balancing loops represents a thermostat keeping a room’s temperature

- Delays introduce oscillations into system behavior, as in a car sales manager trying to keep her inventory consistent

- How to model extraction of a non-renewable resource, such as fossil fuels

- How to model extraction of a renewable resource, such as fish in the sea

Why Systems Perform Well

Systems are capable of accomplishing their purposes remarkably well. They can persist for long periods without any particular oversight, and they can survive changes in the environment remarkably well. Why is that?

Strong systems have three properties:

- Resilience: the ability to bounce back after being stressed

- Self-organization: the ability to make itself more complex

- Hierarchy: the arrangement of a system into layers of systems and subsystems

Creating systems that ignore these three properties leads to brittleness, causing systems to fail under changing circumstances.

Resilience

Think of resilience as the range of conditions in which a system can perform normally. The wider the range of conditions, the more resilient the system. For example, the human body avoids disease by foreign agents, repairs itself after injury, and survives in a wide range of temperatures and food conditions.

The stability of resilience comes from feedback loops that can exist at different layers of abstraction:

- There are feedback loops at the baseline level that restore a system. To increase resilience, there may be multiple feedback loops that serve redundant purposes and can substitute for one another. They may operate through different mechanisms and different time scales.

- Above the baseline loops, there are feedback loops that restore other feedback loops—consider these meta-feedback loops.

- Even further, there are meta-meta feedback loops that create better meta-loops and feedback loops.

At times, we design systems for goals other than resilience. Commonly, we optimize for productivity or efficiency and eliminate feedback loops that seem unnecessary or costly. This can make the system very brittle—it narrows the range of conditions in which the system can operate normally. Minor perturbations can knock the system out of balance.

Self-Organization

Self-organization means that the system is able to make itself more complex. This is useful because the system can diversify, adapt, and improve itself.

Our world’s biology is a self-organizing system. Billions of years ago, a soup of chemicals in water formed a cellular organism, which then formed multicellular organisms, and eventually into thinking, talking humans.

Some organizations quash self-organization, possibly because they optimize toward performance and seek homogeneity, or because they’re afraid of threats to stability. This can explain why some companies reduce their workforces to machines that follow basic instructions and suppress disagreement.

Suppressing self-organization can weaken the resilience of a system and prevent it from adapting to new situations.

Hierarchy

In a hierarchy, subsystems are grouped under a larger system. For example:

- The individual cells in your body are subsystems of the larger system, an organ.

- The organs are in turn subsystems of the larger system of your body.

- You, in turn, are a subsystem of the larger systems of your family, your company, and your community, and so on.

In an efficient hierarchy, the subsystems work well more or less independently, while serving the needs of the larger system. The larger system’s role is to coordinate between the subsystems and help the subsystems perform better.

The arrangement of a complex system into a hierarchy improves efficiency. Each subsystem can take care of itself internally, without needing heavy coordination with other subsystems or the larger system.

Problems can result at both the subsystem or larger system level:

- If the subsystem optimizes for itself and neglects the larger system, the whole system can fail. For example, a single cell in a body can turn cancerous, optimizing for its own growth at the expense of the larger human system.

- The larger system’s role is to help the subsystems work better, and to coordinate work between them. If the larger system exerts too much control, it can suppress self-organization and efficiency.

How We Fail in Systems

We try to understand systems to predict their behavior and know how best to change them. However, we’re often surprised by how differently a system behaves than we expected.

At the core of this confusion is our limitation in comprehension. Our brains prefer simplicity and can only handle so much complexity. We also tend to think in simple cause-effect terms, and in shorter timelines, that prevent us from seeing the full ramifications of our interventions.

These limitations prevent us from seeing things as they really are. They prevent us from designing systems that function robustly, and from intervening in systems in productive ways.

Systems with similar structures tend to have similar archetypes of problems. We’ll explore two examples of these; the full summary includes more.

Escalation

Also known as: Keeping up with the Joneses, arms race

Two or more competitors have individual stocks. Each competitor wants the biggest stock of all. If a competitor falls behind, they try hard to catch up and be the new winner.

This is a reinforcing loop—the higher one stock gets, the higher all the other stocks aim to get, and so on. It can continue at great cost to all competitors until one or more parties bows out or collapses.

A historical example was the Cold War, where the Soviet Union and the United States monitored each others’ munitions and pushed to amass the larger arsenal, at trillions of dollars of expense. A more pedestrian example includes how advertising between competitors can get increasingly prevalent and obnoxious, to try to gain more attention.

Fixing Escalation

The solution is to dampen the feedback wherein competitors are responding to each others’ behaviors.

One approach is to negotiate a mutual stop between competitors. Even though the parties might not be happy about it or may distrust each others’ intentions, a successful agreement can limit the escalation and bring back balancing feedback loops that prevent runaway behavior.

If a negotiation isn’t possible, then the solution is to stop playing the escalation game. The other actors are responding to your behavior. If you deliberately keep a lower stock than the other competitors, they will be content and will stop escalating. This does require you to be able to weather the stock advantage they have over you.

Addiction

Also known as: dependence, shifting the burden to the intervenor

An actor in a system has a problem. In isolation, the actor would need to solve the problem herself. However, a well-meaning intervenor gives the actor a helping hand, alleviating the problem with an intervention.

This in itself isn’t bad, but in addiction, the intervenor helps in such a way that it weakens the ability of the actor to solve the problem herself. Maybe the intervention stifles the development of the actor’s abilities, or it solves a surface-level symptom rather than the root problem.

The problem might appear fixed temporarily, but soon enough, the problem appears again, and in an even more serious form, since the actor is now less capable of solving the problem. The intervenor has to step in and help again to a greater degree. Thus the reinforcing feedback loop is set up—more intervention is required, which in turn further weakens the actor’s ability to solve it, which in turn requires more intervention. Over time, the actor becomes totally dependent on—addicted to—the intervention.

An example is elder care in Western societies: families used to take care of their parents, until nursing homes and social security came along to relieve the burden. In response, people became dependent on these resources and became unable to care for their parents—they bought smaller homes and lost the skills and desire to care.

Fixing Addiction

When you intervene in a system:

- Try to first diagnose the root cause of the issue. Why is the system unable to take care of itself?

- Then design an intervention that will solve the root cause, and that won’t weaken the system’s ability to take care of itself.

- After you intervene, plan to remove yourself from the system promptly.

More System Problems

Read the full summary to learn more common system problems:

- Policy resistance, where a policy seems to have little effect on the system because the actors resist its influence. Example: The war on drugs.

- The rich get richer, where the winner gets a greater share of limited resources and progressively outcompetes the loser. Example: monopolies in the marketplace.

- Drift to low performance, where a performance standard depends on previous performance, instead of having absolute standards. This can cause a vicious cycle of ever-worsening standards. Example: a business loses market share, each time believing, “well, it’s not that much worse than last year.”

Improving as a Systems Thinker

Learning to think in systems is a lifelong process. The world is so endlessly complex that there is always something new to learn. Once you think you have a good handle on a system, it behaves in ways that surprise you and require you to revise your model.

And even if you understand a system well and believe you know what should be changed, actually implementing the change is a whole other challenge.

Here’s guidance on how to become a better systems thinker:

- To understand a system, first watch to see how it behaves. Research its history—how did this system get here? Get data—chart important metrics over time, and tease out their relationships with each other

- Expand your boundaries. Think in both short and long timespans—how will the system behave 10 generations from now? Think across disciplines—to understand complex systems, you’ll need to understand fields as wide as psychology, economics, religion, and biology.

- Articulate your model. As you understand a system, put pen to paper and draw a system diagram. Put into place the system elements and show how they interconnect. Drawing your system diagram makes explicit your assumptions about the system and how it works.

- Expose this model to other credible people and invite their feedback. They will question your assumptions and push you to improve your understanding. You will have to admit your mistakes, redraw your model, and this trains your mental flexibility.

- Decide where to intervene. Most interventions fixate on tweaking mere numbers in the system structure (such as department budgets and national interest rates). There are much higher-leverage points to intervene, such as weakening the effect of reinforcing feedback loops, improving the system’s capacity for self-organization, or resetting the system’s goals.

- Probe your intervention to its deepest human layers. When probing a system and investigating why interventions don’t work, you may bring up deep questions of human existence. You might bemoan people in the system for being blind to obvious data, and if only they saw things as you did, the problem would be fixed instantly. But this raises deeper questions: How does anyone process the data they receive? How do people view the same data through very different cognitive filters?

Introduction: Seeing Things as Systems

What is a system? A system is 1) a group of things that 2) interact to 3) produce a pattern of behavior.

Many things in the world operate as systems.

- The human liver is a group of cells that interact to detoxify the blood, among other functions. The liver is, in turn, part of the larger system of the human body.

- A football team consists of a group of players on the field, each with a specific role that interacts with the others. The team also consists of coaches, support staff, and fans.

- Within the system of a corporation, people, machines, and information work together to achieve the corporation’s goals. This corporation then takes place within the larger system of the economy.

Systems may look different on the surface, but if they have the same underlying structure, they tend to behave similarly.

- For example, consider the simple system of a bathtub. There is a spout that adds water to the system, and a drain that removes water from the system. If the spout adds water faster than it drains, the bathtub will fill and the water level will rise. Conversely, if the drain removes water faster than the spout adds water, the bathtub will empty.

- Now consider the system of the world population. From a system point of view, it looks similar to the bathtub. The birth rate adds people to the population; death removes people from the population. If the birth rate exceeds the mortality rate, the population will rise. If people die faster than they are born, the population will fall.

In reality, if you look deeper, the world population is a much more complex system—it’s subject to the economy, health science, and politics, each of which is its own complicated system. But from a certain simplified vantage point, the bathtub and the world population behave similarly.

Understanding the underlying system and how it behaves may be the best way to change the system.

Cause and Effect Isn’t Enough

When we try to explain events in the world, we tend to look for simple cause and effect relationships.

- An oil company is blamed for greedily driving up the price of oil.

- When you get sick, you blame the cold virus for attacking your body.

- Drug addiction is blamed on the weak fortitude of the people addicted to drugs.

This simplicity is reassuring in some ways. Turn this knob, and you solve the problem—easy. In turn, it becomes easy to blame people who do not turn the knob the way you want it to be turned.

However, reality tends to be more complex than simple cause and effect relationships, because they are a product of complicated systems. Systems consist of a large set of components and relationships; a system’s behavior is not the result of a single outside force, but rather the result of how the system is set up.

- The oil company’s actions could not cause global oil prices to rise, if the system didn’t allow it to exert this control. This relates to how readily people consume oil, the lack of viable energy alternatives to oil, and national pricing policies. All these system properties make economies vulnerable to oil suppliers.

- A flu virus could not make you sick if your body did not create the conditions that allowed it to thrive. The virus is not attacking you—it is interacting with the system of your body.

- Drug addicts participate in a system that includes drug sellers who want to make money; governments that make drugs illegal and enforce laws with police; nonaddicts who influence how society balances punishing criminals versus rehabilitating them.

When viewed from this system lens, causing change is much more difficult than applying a single cause and expecting an effect. It requires an upheaval of the system itself, with all its components and connections.

- You cannot neutralize an oil company’s power over an economy without also changing how people and companies consume oil and the availability of viable alternatives to oil.

- You cannot eradicate drug addiction without also changing the laws around drugs, the economic incentives for drug distribution, and the mindset of the voting public.

Without understanding the system that produces a problem, you cannot design effective solutions that solve the problem. Indeed, many “solutions” have worsened the problem because they ignored how the system was set up.

This book will teach you to be a systems thinker.

- First, you’ll learn the definition of a system and how a system is set up.

- Then, you’ll see the “systems zoo”—a variety of examples of systems and how they behave.

- Finally, you’ll learn why systems often behave unexpectedly and common problems in changing systems.

As a systems thinker, you’ll begin to see systems everywhere, and you’ll look at the world in a new way. In so doing, you’ll be more effective at restructuring systems to achieve the outcome you want.

Part 1: What Are Systems? | Chapter 1: Definitions

A system is composed of three things:

- Elements: The individual things in the system

- Interconnections: The relationships between the elements

- Purpose or Function: What the system achieves

To define it more cohesively, a system is a set of elements that is interconnected in a way that achieves its function.

Many things in ordinary life are systems. Let’s define how a professional football team is a system:

- Elements: The players, the coaches, the field of play, the ball

- Interconnections: The rules of football, the way players in specific roles interact with each other, how the coaches instruct the players, how the laws of physics govern how the ball moves

- Purpose: To win football games, to have fun, to make money

As you look around the world, you’ll see systems everywhere. So what is not a system? A set of elements that are not interconnected in a meaningful way or overall function is not a system. For example, a pile of gravel that happens to be on a road is not a system—it’s not interconnected with other elements and does not serve a discernible purpose.

In this chapter, we’ll dive deeper into understanding the three attributes of a system. We’ll then understand how systems behave over time, and how the interconnections can drive system behavior.

(Shortform note: in this chapter we’ll develop an extended example of a football team beyond what’s contained in the book, but in a way that’s consistent with its ideas. You should actively apply the ideas to develop your own examples of systems, such as a corporation, a university, a tree, or the government.)

Describing a System

Let’s go deeper into understanding the three attributes of a system.

Elements

Elements are usually the most noticeable. They are the things that make up the system. The football team consists of players, coaches, and a ball. If you zoom out a bit further and define a larger system, the elements can also include the football fans, the city the team resides in, the staff that supports the team, and so on.

Elements don’t need to be tangible things. The system of a football team also consists of intangibles like the pride that fans have for their team, the reputation of players in the league, or the motivation to practice.

You can define an endless number of elements in any system. Before you go too deep down this rabbit hole, start looking for the interconnections between elements.

Interconnections

Interconnections are how the elements relate to each other. These interconnections can be physical in nature. Take the football team again:

- The players line up in a particular formation, with specific roles in specific places

- The individual players pass the football to each other

- The players maneuver themselves against and around the opposing teams’ players

- The team’s fans surround the players in a circular arena to watch the game

Interconnections can also be intangible, often through the flow of information.

- During a game, the coach receives information from the field, then decides on a strategy and communicates that strategy to the quarterback

- A television broadcaster communicates the information about the game to an audience nationwide

- Outside of games, the training staff uses information from the game to decide how to develop the players

- A player receives information from his agent about openings at other teams

The information interconnections may be harder to see at first, but they’re often vital to how the system operates.

Purpose

The purpose or function is what the system achieves.

Of the three elements, the purpose is often the hardest to discern. It’s not often made explicit, such as in the case of a tree.

The best way to figure out a system’s purpose is to see what it actually does. The way a system behaves and its result is a reflection of the system’s purpose.

- A football team’s purpose is often to win games. But looking at its performance of individual players, you might find that their purpose is to make more money or attract attention.

- A national government may communicate that its purpose is to take care of the poor and reduce inequality, but if it makes little effort toward this goal, it’s not actually a function of the system.

- Many systems don’t have explicitly stated purposes, so, once again, you can observe what it does. What is the purpose of a tree? To grow as large as it can within its lifetime; to spread seeds and reproduce itself; to compete against other plants for limited resources.

A vital purpose of most systems is to perpetuate itself.

Which Aspect Is Most Important?

Which of the three aspects of a system is most important? The elements, interconnections, and purposes are all necessary, but they have different relative importances.

To think about this, consider changing each item in a system one by one.

Changing elements: You can change the individual players and coaches, but if you keep the same interconnections and purpose, it’s still clearly a football team. Likewise, you can change the members of the US Senate or a corporation, but they still maintain their identities. Thus, the specific elements are usually the least important in the system. (Shortform note: This is related to the Ship of Theseus thought experiment.)

Changing interconnections: Changing the interconnections can dramatically change the system. Imagine changing the rules of the game from football to rugby, while keeping the same players. Or imagine a system where the players paid money to watch the fans. These are certainly not recognizably football teams, even if all the elements remain the same.

Changing purpose: Changing the purpose can also be drastic. What if the goal of the team were to lose as many games as possible? What if the purpose were to make news headlines? The system would be very different, even if the elements and interconnections stayed the same.

Therefore, typically, the purpose is often the most important determinant of a system, followed by interconnections, then by elements.

However, sometimes changing an important element can also change the interconnections or the purpose. Changing China’s leadership from Mao to Deng Xiaoping dramatically changed the nation’s direction; even though the one billion people and millions of organizations were exactly identical, their interconnections and their purpose became very different.

How Systems Relate to Each Other

Because you can now see systems everywhere you look, you might have seen that systems can be composed of other systems, and so on in a fractal-like pattern.

For example:

- Each player on a football team is himself a complex system, consisting of his organ systems, his thinking, his own motivations.

- The multiple players together form a system of the playing team on the field.

- The players with the coaching staff form an overall system at a team level.

- The team combines with its fans and the overall city to form another system.

- The team combines with the other teams in the sport to form another system at the league level.

- The league combines with the other sports leagues in the world to form another system.

The systems can thus get quite complex, as we’ll explore throughout the summary.

The individual subsystems may have conflicting purposes from the overall system purpose, which can lower function of the system. For example, if the individual players on a football team care more about their personal reputation than the success of the team, the overall team system will perform poorly. For a system to function effectively, its subsystems must work in harmony with the overall system.

Exercise: Define a System

Pick a system that you want to understand better. If you can’t think of one, here are suggestions: your employer; your favorite store; your political party; an organism.

What are the major elements of the system?

What are the key interconnections between these elements? Think about physical interconnections, as well as intangible ones based on transferring information.

What are the major purposes of the system? Remember, look at what the system actually does, not what its stated purpose is.

Chapter 1-2: System Behavior

Next, we’ll understand how systems behave over time, by considering stocks and flows. This forms the basic foundation that lets us build up into more complex systems.

Stocks and Flows

A stock represents the elements in a system that you can see, count or measure. It can be commonly thought of as an inventory, a store, or a backlog.

Flows are the means by which the stocks change over time. Inflows increase the level of stock, while outflows decrease the level of stock.

Let’s take a simple system: a bathtub.

- The stock is the amount of water in the tub.

- The inflow is water coming from the faucet into the tub. This raises the stock.

- The outflow is the drain that removes water from the tub. This decreases the stock.

This can be drawn on a stock-and-flow diagram, as here:

The clouds signify wherever the inflow comes from, and wherever the outflow goes to. To simplify our understanding of a system, we draw boundaries for what’s important for understanding the system, and ignore much of the outside world.

Many systems are analogous to the bathtub:

- In fossil fuels, the stock is the reservoir of fossil fuels. Mining lowers the stock, while natural processes increase the stock.

- The world population is a stock of people. The population grows with births and shrinks with deaths.

- Your self-confidence is a stock. It grows with compliments and personal triumphs. It shrinks with project failures and insults.

System Dynamics

Systems like bathtubs and world populations are usually not static. They change over time—the inflows and outflows change, which causes the stocks to change.

Let’s consider how you can change the flows in a bathtub, by manipulating the inflow and the outflow:

- The bathtub starts off empty. You plug the drain and turn on the faucet. This causes the water level (or the stock) to rise.

- When the bathtub is full, you turn off the faucet. The water level stays the same, because water is neither flowing in nor out.

- You open the drain. The water level starts decreasing.

- At some point halfway, you turn on the drain again. The water is flowing in at the same rate that it’s leaving, so the water level stays the same.

This behavior can be put on a graph, which visualizes the system over time.

Systems thinkers use graphs to understand the trend of how a system changes, not just individual events or how the stock looks currently.

The bathtub should be an intuitive model, and it’s simple as it represents just one stock, one inflow, and one outflow. But from this basic example you can find a few general properties of systems:

- If the inflows exceed the outflows, the stock will rise.

- If the outflows exceed the inflows, the stock will fall.

- If the outflows balance the inflows, the stock will stay the same, at a level of “dynamic equilibrium.”

Where We Focus

As humans, when we look at systems, we tend to focus more on stocks than on flows. (Shortform note: This might be because the stock is much more obvious and tangible than the flows. This is also related to how elements in a system are more easily recognizable than the Interconnections.)

Furthermore, we tend to focus more on inflows than on outflows.

- When thinking about how the world population is growing, we naturally think about how increasing births must be driving the trend. We think less about how preventing death through better medical care also grows the population.

- Likewise, a company that wants to increase its headcount does so instinctively by hiring more people. It doesn’t often think as hard about how to reduce the outflow of people who quit or are fired.

Changing the outflows can have very different costs than changing the inflows.

Properties of Stocks and Flows

Stocks take time to change. In a bathtub, think about how quick it is to change the inflow or outflow. It takes just a second to turn on the faucet. It takes minutes to fill the tub.

Why do stocks change so gradually? Because it takes time for the flows to flow. As a result, stocks change slowly. They act as buffers, delays, and lags. They are shock absorbers to the system.

From a human point of view, this has both benefits and drawbacks. On one hand, stocks represent stability. They let inflows and outflows go out of balance for a period of time. A stock buys you time to solve the problem and experiment.

- A car’s gas tank gives the car operational stability. The engine can draw gas from the tank as it needs it. In contrast, imagine if you had to provide gas every second to the car at exactly the moment it needed it, or the engine would shut down. The storage tank gives the car system stability.

- Your bank account stores money and gives your life stability. If you get fired from your job, the inflow of money will stop, but you can take money from your stock to continue living and figure out how to solve the problem.

- Likewise, inventories for retail stores help them deal with different rates of buying. Water reservoirs help farmers deal with fluctuations in rainfall.

On the other hand, a slowly-changing stock means things can’t change overnight.

- If we cut down all the trees in a rainforest, they can’t be planted overnight. They can only be replenished as quickly as the inflow of new trees.

- If a population’s skills become meaningless because of technology, you can’t re-educate the workforce instantaneously. It takes time for the information to work its way through the system and to flow to the population.

If you understand that stocks take time to change, you’ll have more patience to guide the system to good performance.

Decisions Influence Stocks

As agents in a system, we make decisions to adjust the level of a stock to where we think it should be.

- Your financial decisions depend on the stock of money in your bank account. If you feel you have too little money, you decrease spending and increase earnings to increase the stock of money.

- If a store has too much inventory, it runs sales or increases ads to decrease stock.

If you look at the world through a systems lens, you’ll see a large number of stocks, and flows that adjust the levels of stocks.

Feedback Loops

Systems often produce behaviors that are persistent over time. In one type of case, the system seems self-correcting—stocks stay around a certain level. In another case, the system seems to spiral out of control—it either rockets up exponentially, or it shrinks very quickly.

When a behavior is persistent like this, it’s likely governed by a feedback loop. Loops form when changes in a stock affect the flows of the stock.

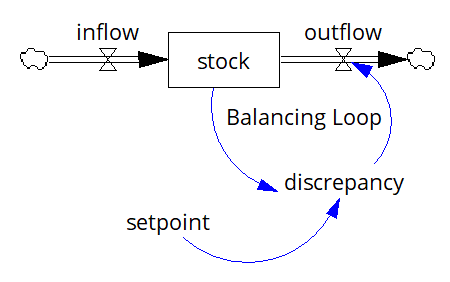

Balancing Feedback Loops (Stabilizing)

(Shortform note: Balancing feedback loops are also known as negative feedback loops or self-regulation.)

In balancing feedback loops, there is an acceptable setpoint of stock. If the stock changes relative to this acceptable level, the flows change to push it back to the acceptable level.

- If the stock dips below this level, the inflows increase and the outflows decrease, to increase the stock level.

- If the stock rises above the acceptable level, the inflows decrease and the outflows increase, to decrease the stock level.

An intuitive example is keeping a bathtub water level steady.

- If the level is too low, plug the drain and turn on the faucet.

- If the level is too high and the water spills out of the tub, open the drain and turn off the faucet.

Your bank account is another example of balancing feedback loops.

- If the stock of money is below what’s acceptably comfortable to you, you’ll likely work more and spend less money.

- In contrast, if you have a windfall and money rises above your acceptable level, you’ll likely work less and spend more.

Balancing feedback loops tend to create stability, and they keep a stock within an acceptable range.

In a stock-and-flow diagram, balancing feedback loops look something like this:

A property of balancing feedback loops is that the further away the stock is from the desired level, the faster it changes.

- A boiling cup of water cools its temperature more quickly than a lukewarm cup of water.

- For your personal finances, you would behave much more extremely if you suddenly became bankrupt, than if you lost $100.

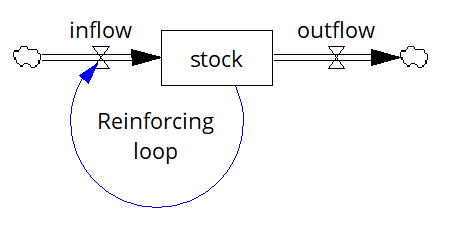

Reinforcing Feedback Loops (Runaway)

(Shortform note: Reinforcing feedback loops are also known as positive feedback loops, vicious cycles, virtuous cycles, flywheel effects, snowballing, compound growth, or exponential growth.)

Reinforcing feedback loops have the opposite effect of balancing feedback loops—they amplify the change in stock and cause it to grow more quickly or shrink more quickly.

- As a stock level increases, the inflow also increases and the outflow decreases, causing the stock level to further rise.

- As a stock level decreases, the inflow also decreases and the outflow increases, causing the stock level to further decrease.

Here are examples of runaway loops in the positive direction:

- The more people there are in the world, the more they reproduce, which increases the stock of the world population.

- A healthy national economy grows in a reinforcing loop. In a nation, the more factories and people you have, the more you can produce. The more you produce, the more you can invest back in more factories and educating people.

In a stock-and-flow diagram, reinforcing feedback loops look something like this:

Rule of 72

Since we think about compound growth a lot, there’s a rule of thumb called the Rule of 72 that lets you calculate the time it takes a stock to double. Take the current growth rate in percent, divide 72 by that number, and you’ll get the number of periods it takes to double.

For example, if your annual growth rate of investments is 4%, it will take 72 / 4 = 18 years to double. If it grows at 6%, it will take 72 / 6 = 12 years to double.

(Shortform note: The book cites the rule of 70, but 72 tends to be more commonly used, since more numbers divide evenly into 72 than 70.)

Here are examples of runaway loops in the negative direction:

- In agriculture, plant roots help retain soil. The more that soil is eroded, the less roots can grow, which causes more erosion.

- In a natural emergency, a store may have a sale on its goods. The lower the stock of a good like toilet paper, the more fervently people want to buy it, which causes the stock to shrink further.

Systems Thinking

As you continue looking at the world through a systems lens, you’ll see feedback loops everywhere.

In fact, here’s a challenge: try thinking of any decision you make without a feedback loop of some kind. Can you think of any?

You might start finding that many things influence each other in reciprocal ways. Instead of pure cause and effect, you might see that the effect actually influences the cause.

- If population growth causes poverty, does poverty also cause population growth?

- If the government makes a bad decision for the nation, did the nation do something to cause the government to make that bad decision?

Invert your thinking. If A causes B, does B also cause A?

This type of systems thinking makes blame much more complicated. It’s not an easy cause and effect relationship. It’s a system of interconnected parts and complicated feedback loops.

Exercise: Feedback Loops

Think about everyday systems and how feedback loops affect them.

Can you think of any decision you make where a feedback loop is not involved? What is it?

Think harder—in what way does what you’re deciding about influence what you decide?

Think of a recent time where you blamed a problem on something. Phrase it as “A caused B.” (Try not to think about a single person making a mistake, but rather about a system-level problem, such as a political or societal issue.)

Now invert the situation. Is it possible that B caused A? How could this be true?

Chapter 2-1: Building More Complicated Systems

In reality, systems are much more complex than the simple examples we’ve covered so far.

- A single stock may not just have an inflow and outflow, but really have multiple flows in and out, as well as multiple balancing and reinforcing loops working in opposite directions.

- A single flow may affect dozens of stocks.

- Feedback loops affect each other, reinforcing each other or balancing each other.

For example, the world population has an inflow representing birth rate, but birth rate is influenced by a vast number of inputs, such as the overall economy, healthcare, and politics, which are themselves complex systems.

In this chapter, we’ll take what we’ve learned and build up to more complicated systems, which are simplistic models of real-world systems. The author calls this collection of systems a “zoo,” which is an appropriate metaphor. Like in a zoo, these animals are removed from their natural complex ecosystem and put in an artificially simplistic environment for observation. But they give a hint of patterns in the real world and yield surprisingly insightful lessons.

One Stock + Two Balancing Loops

First, we’ll look at a system with one stock and two balancing loops that compete against each other. We know that a balancing loop tries to bring a stock back to a setpoint. What happens when two balancing loops have different setpoints but act on the same stock?

The concrete example we’ll use is a thermostat that heats a room that is surrounded by a cold environment.

- The stock is the temperature of the room.

- One balancing loop is the cold outside environment, which constantly absorbs heat from the room that leaks through the walls and windows. This loop tries to bring the room’s temperature down to the cold outside temperature.

- The other balancing loop is the thermostat and the furnace, which tries to bring the room’s temperature up to the thermostat temperature.

The stock and flow diagram looks like this:

So how does the system behave? It depends on which balancing loop is stronger:

- If the room insulation is airtight and the furnace is strong, the heating loop is much stronger. The temperature will be consistently maintained near the thermostat setting (say, 68°F).

- If the room is very leaky (say, a window is broken) and the furnace is weak, the cooling loop is much stronger. The temperature will hover closely to the outside temperature (say, 30°F).

Where exactly the room stabilizes its temperature depends on the relative strength of the balancing loops. The stronger loop will drive the stock closer toward its setpoint. The general takeaway: in a system with multiple competing loops, the loop that dominates the system determines the system’s behavior.

One implication of two competing loops is that the stock levels off at a point near to the stronger loop’s setpoint, but not exactly at it. If a thermostat is set to 68°F, the room temperature will level off slightly below 68°F, because heat continues to leak from the stock even as the furnace generates heat. (For this reason, people often set the thermostat to a bit above the temperature they want, or thermostats temporarily overshoot to bring the temperature above the setpoint.)

The strength of the loops may also vary over time. For example, the outside temperature drops during night and rises during day. Thus, the cooling loop is stronger at night and weaker during the day. If the heating loop stayed at the same strength throughout the day, then you’d find the room temperature would drop more at night than during the day. By understanding the strengths of the loops and how they fluctuate over time, you can predict the room temperature.

A thermostat is fairly unimportant in the grand scheme of things, but think about how this system applies to your paying off credit card debt. To pay off the debt, you need to pay not just the current bill but also cover the interest generated while you’re paying—otherwise, you will never quite pay off your bill. This applies equally to the national debt.

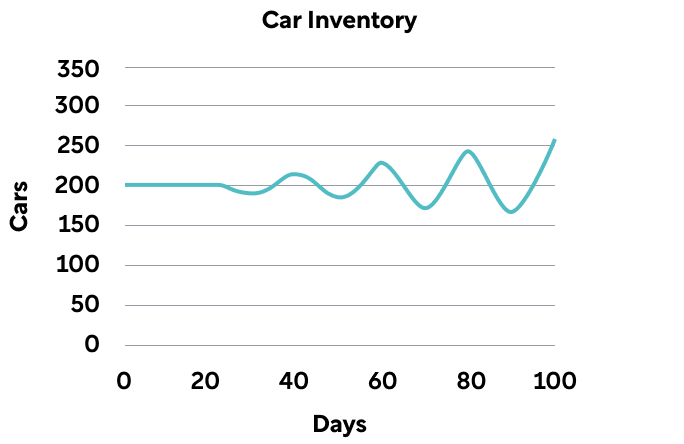

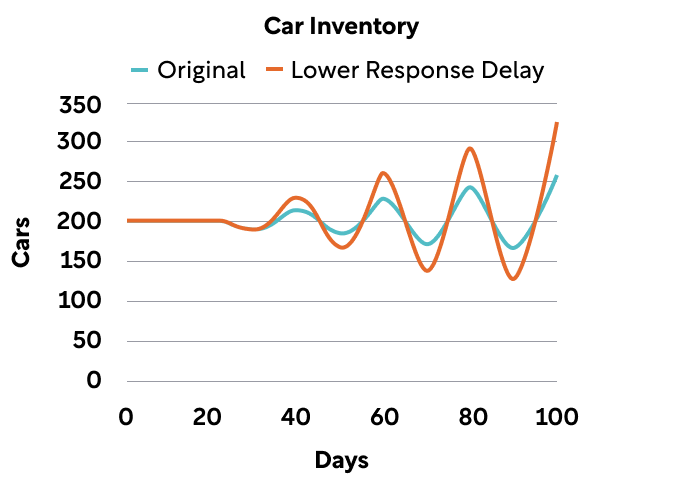

One Stock + Two Balancing Loops, With Delay

We’ll now take the system we just discussed—one stock with two balancing loops—and introduce delays. Delays are common in the real world. It takes time to transmit information, to process the information, to act on the information, and to get the result of your actions. All of these delays disrupt how the system behaves.

For this example, imagine the manager of a car dealership who has to stock her car lot for sale:

- The stock is the inventory of cars on the lot.

- One balancing loop is the outflow of cars as customers buy them.

- The other balancing loop is the inflow of cars from the manufacturer. In response to too low of a stock, the manager orders cars from the factory.

The manager wants to keep the inventory at a set number of cars to cover ten days’ worth of sales. In an ideal world, every time a customer drives a car off the lot, a new one instantaneously appears to replace it. The car stock is kept at exactly the same number.

Of course, reality doesn’t work this way. In practice, there are several key delays that hamper the response time:

- A perception delay: instead of deciding based on each day’s data, the manager averages out the inventory changes over the past three days. This prevents the manager from overreacting to short-term fluctuations, but it introduces a delay in case of a major sudden change.

- A response delay: instead of ordering all the cars she needs at once, the manager meters out the order over three days. This again avoids over-corrections.

- A delivery delay: it takes a week for the factory to get the order and deliver the cars.

At an equilibrium, these delays aren’t a big deal. The manager can figure out the typical rate of car sales and adjust for all the delays. The car lot stays at a steady number.

But let’s look at a new situation—say there’s a sudden, permanent increase in daily car sales of 15%. In the long run, since the manager wants to stock 10 days’ worth of cars in the lot, she needs to increase her inventory. Again, in an ideal world, the cars would just appear instantaneously on the lot without any delay, and she’d be set.

But the real world has delays. What’s the effect of all of these delays? Surprisingly, the delays cause oscillations:

Why does this happen? In essence, the delays cause decision making that falls out of sync with what the car lot really needs:

- While the sales increase, the manager is averaging sales to make sure the sales boost is real. When she’s sure it’s real, she increases her orders to the factory.

- However, there’s a delay of a week for the cars to arrive. During this time, the inventory keeps shrinking. The car lot is now well under its ideal car count and still dropping. The manager panics and increases the orders of cars.

- At long last, the cars from her first orders arrive. They gradually replenish the inventory and for a moment the car lot is at the ideal inventory size.

- But the largest orders the manager recently placed in a panic are still coming. The manager can’t cancel the orders.

- As the cars pile up, the manager wonders how she’s going to get rid of all the cars. She freezes her orders to the factory.

- As the car deliveries stop, the sales keep happening, and the inventory gets drawn down again. The whole cycle repeats.

As an analogy, if you’ve taken a shower where it takes a long time for turning the knob to do anything, you’ve experienced the wild, unpleasant oscillations in water temperature. You don’t get quick feedback on your actions—if the water’s too cold, you turn the knob all the way hot; then it gets scalding, and you quickly clamp it down; then the water gets too cold, and so on.

Fixing Oscillations

Oscillations can cause more problems.

How do you fix this? One intuitive reaction is to see the delays as bad. Surely, shortening the reaction time should solve the problem! The car manager decides to shorten her perception delay, reacting to two days’ data instead of three, and shortening her response delay, ordering the entire shortfall in one go, rather than spacing it out.

This actually makes things worse. The oscillations increase dramatically:

(Shortform note: this graph is an approximation to illustrate the point. System analysts build quantitative models to produce more accurate charts.)

In essence, shorter delays cause larger overreactions—at the car lot’s lowest points, the manager places large orders multiple times in succession. This causes a huge buildup of cars, which takes a long time to draw down. The cycle repeats.

Counter-intuitively, the better reaction to oscillations is actually to slow reaction time. Oscillations are a sign of overreacting. The manager should under-react—if she increased her delays from 3 days to 6 days, the oscillations would dampen quite a lot:

The Importance of Delays

As you’ve seen, delays affect systems a lot, in somewhat unpredictable ways. That’s why systems thinkers are obsessed with identifying delays and studying their impact.

This example just represents a single simple car lot. Imagine things like this happening throughout the broader economy, in hundreds of thousands of places, all interconnected. All the car lots around the world are connected to the manufacturer, which is connected to the parts makers, who are connected to suppliers of steel, rubber, electronics. Every single member here has its own idiosyncratic delays and oscillations—imagine the coordination it takes to produce new cars and ship them nationwide!

One Stock + One Reinforcing Loop, One Balancing Loop

Next, we’ll look at a system with one stock and two loops that compete against each other—one reinforcing, and one balancing.

The concrete example we’ll use is the world population.

- The population is the stock.

- The reinforcing loop is birth rate—the more people there are, the more who reproduce. By itself, this leads to natural exponential growth.

- The balancing loop is deaths—the more people there are, the more who die. (Shortform note: In essence, the setpoint of this balancing loop is 0, and the further away from 0 the stock is, the more people who will die.)

The stock and flow diagram looks like this:

As with the previous system, the relative strength of the two competing loops determines how the stock changes over time.

- If the birth rate is higher than the death rate, the population will grow exponentially. This is where the world overall currently is.

- If the death rate becomes larger than the birth rate, the population would shrink. (This can happen if the birth rate plummets, or the death rate skyrockets, or both.)

- If they are equal, the population will stay the same.

Different circumstances can drive the relative strength of the birth or death loop:

- Data suggests that as countries get wealthier, birth rates fall. Therefore, poorer countries with high current birth rates may not retain high birth rates as their economies develop.

- A lethal, contagious disease could drastically increase the death rate. For instance, during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, projections of populations in areas with high HIV prevalence had to account for higher mortality.

- Birth rate could also fall due to social factors, such as lower interest in raising children or fertility issues.

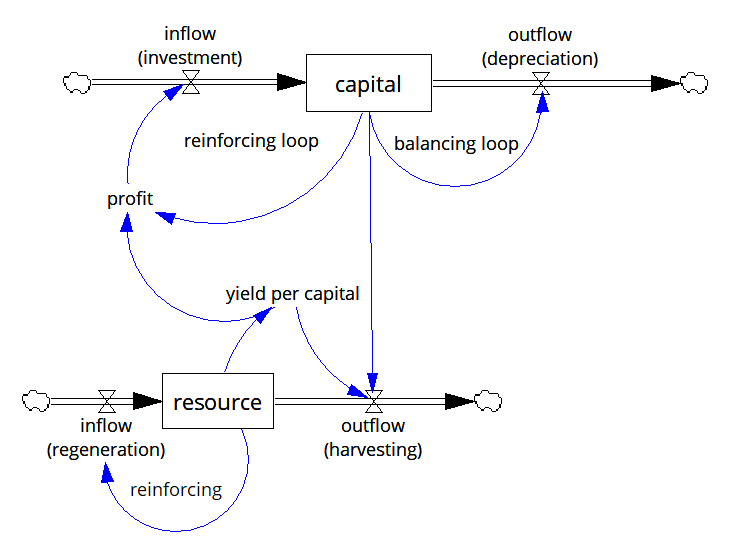

The System of the Economy

The economy works similarly to the world population, in that it fits the same system model of a stock, one reinforcing loop, and one balancing loop:

- The stock is capital. These are assets that do useful work, such as factories, machines, and labor.

- The reinforcing loop is reinvestment. The excess output that is produced can be reinvested into producing more capital stock, which in turn increases output.

- The balancing loop is depreciation, or the decrease in the usefulness of the capital stock. This includes machines breaking down and labor skills becoming obsolete.

As with the world population, the strength of the two loops determines the behavior of the system. If reinvestment is stronger than depreciation, the capital stock will rise. Otherwise, the capital stock will fall, and the economy will decline.

And, again, changing the circumstances can change the strengths of the loops. New technology that reduces the breakdown of industrial machines decreases depreciation. Inversely, political actions that reduce reinvestment can weaken an economy.

You can see how two systems that look very superficially different actually behave similarly. This is the type of insight that systems thinking yields.

And of course, the population and economy are inextricably intertwined. People contribute labor to the economy and they consume within it; likewise, the economy affects the population’s birth rates and death rates. Systems can get complicated very quickly.

Chapter 2-2: Two-Stock Systems

So far we’ve just focused on one-stock systems. In the models, we haven’t worried too much about where the inputs came from and how much there were—the population model assumes infinite food, the thermostat model assumes infinite gas to the furnace.

But in the real world, the inputs have to come from somewhere. In a system model, the inflow into a stock comes from another stock, which is finite. This finite stock causes a constraint on growth—the population can’t grow forever, and the economy can’t grow forever.

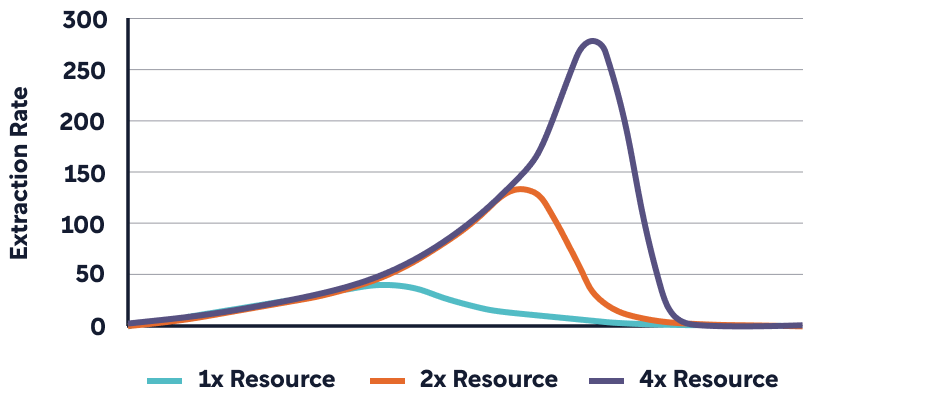

We’ll explore this here with two system models, one with a non-renewable stock (oil mining) and one with a renewable stock (commercial fishing). Changing whether the stock is renewable changes the implications of how growth ends.

Renewable Stock and a Non-Renewable Stock

Consider a reservoir of oil underground. The stock of oil is finite. There is an outflow as the oil is mined. (Shortform note: There is also a very slow inflow of generation of fossil fuels through geological processes, but this occurs over millions of years and is so slow that it’s irrelevant in this situation.)

The company that decides to mine this oil reservoir is a system. The system looks a lot like the system of the economy we just discussed: there is a capital stock (for example, building a mining rig), an inflow of investment in a reinforcing loop, and an outflow of depreciation in a balancing loop.

These two systems are connected by one element—the profit from the oil that is mined. Simplistically, the more oil that is mined, the higher the total profit, which is reinvested into the capital stock; this higher capital stock then mines the resource at a faster rate. In this simplistic system, the capital stock would just grow exponentially, mining faster and faster until the stock is depleted.

But we’ll add one complication to this system—the oil gets harder to extract as the stock goes down. In the real world, this is true—the oil gets deeper and needs more drilling to access, or it becomes more dilute and more costly to purify.

This builds a more complicated feedback loop that ties together the two systems:

- The more oil that is extracted, the more the profit, and the more reinvestment into capital.

- The more capital, the faster oil is extracted, and the lower the stock.

- The lower the stock, the more costly it becomes to extract oil, and the lower the profit.

- The lower the profit, the lower the capital investment rate.

This feedback loop leads to a predictable behavior of the system:

- While the oil is easy to extract, profit grows and is reinvested in capital.

- At a certain point when the stock gets low enough, the marginal barrel of oil becomes unprofitable to extract.

- Since profits have dwindled, it no longer makes sense to reinvest in capital stock. The stock depreciates over time, which causes the extraction rate to fall.

- The stock is not depleted to zero—a certain amount of oil remains in the ground, too costly to mine.

Oil companies clearly know this behavior, so before an oil field runs out, they’ve already invested in discovering new oil sources elsewhere.

Implications of the System

Now that you understand the behavior of the system, nudges to different points in the system can influence its behavior:

- New technology can increase the efficiency of extracting oil, thus decreasing the cost. This can allow a reservoir that was unprofitable 40 years ago to become profitable again. (Shortform note: This is what hydraulic fracturing technology, or “fracking,” enabled—a way to extract natural gases that were previously unprofitable to capture.)

- So far, we have been fixing the price per oil barrel. In reality, price fluctuates.

- If the price of oil suddenly skyrockets, oil mines that were unprofitable at a certain cost of mining can become profitable again.

- In contrast, if the price of oil plummets, many oil fields shut down, since the cost of operating exceeds the price of oil they extract. (Shortform note: When oil prices plummet, say due to price wars between foreign oil producers, it might sound good for the average consumer. But it’s bad for the domestic energy industry (oil rigs need to shut down and workers are laid off), and it’s also bad for investment in alternative energy development (there is less incentive to develop alternatives when fossil fuels are cheap).)

The book explores a final consequence of this system—increasing the size of the stock does not proportionately increase the time that the resource lasts. If the size of the oil reservoir doubled, the reservoir would not last for double the amount of time. This is because the capital stock grows exponentially—even if the global oil reservoir were instantaneously doubled, at a capital growth rate of 5% per year, the peak extraction time would only be extended by 14 years (recall the rule of 72 from earlier). And the higher capital stock grows, the steeper the plummet when the stock becomes depleted (in real terms, these are jobs that disappear and communities that are battered).

(Shortform note: While the book steers away from explicit political statements, the implication is that the more we reinvest in harvesting a nonrenewable resource like fossil fuels and avoid developing alternatives, the higher the capital stock and extraction rate will grow, and the steeper the fall will be when the resource depletes.)

Two Renewable Stocks

We also depend on stocks that are renewable, that replenish themselves after we harvest from them. Examples include lumber from trees we can replant, and farming animals and plants that we can replenish.

Let’s consider the example of fishing from the ocean. The extraction system of capital stock is the same as with oil mining, except instead of oil rigs, the capital stock represents fishing vessels. The capital stock has an inflow of reinvestment, and an outflow of depreciation. The capital stock determines the harvest rate of the fish.

However, the stock it is harvesting from is now renewable—the fish population has a runaway loop that creates an inflow of more fish.

There are a few nuances to the situation:

- Like oil, the lower the fish population, the more expensive it becomes to catch them, and the less profitable fishing is.

- Below a certain stock level, the regeneration of fish may stop—when there are too few fish, they find it harder to find each other and mate. This can cause extinction of a species.

Depending on how the fishing industry behaves, we can arrive at very different system outcomes.

Outcome 1: Dynamic Equilibrium

The fishing industry can balance its harvest rate so that it matches the inflow rate of fish. The fish population is held at a constant stock level.

This also requires that the industry constrain its level of capital stock to be steady. It reinvests in capital stock only to balance the rate of depreciation, thus keeping the harvest rate steady. If it invested any more, the capital stock would rise, and the harvest rate would increase beyond the replenishment rate of the population. This leads to the next system outcome.

Outcome 2: Overfishing, with Oscillations

Here, the industry’s harvesting rate exceeds the replenishment rate of the population. Oscillations appear because there is a natural feedback loop at work:

- For some time, the harvest rate increases and reinvestment increases, thus decreasing the fish stock.

- As the fish stock decreases, it becomes more costly to farm fish. The inflow of reinvestment into capital stock decreases, and the capital stock level decreases due to depreciation.

- As the stock decreases, the harvest rate decreases, allowing the fish to replenish itself.

- As the fish stock rises, fishing gradually becomes more profitable again, thus encouraging more reinvestment, and restarting the oscillation cycle.

As with the car manager on her car lot, oscillations appear in the system due to delays. It takes time for the fishing industry to respond to a declining fish population by reducing investment, and it takes time to reinvest once fishing is good again.

This might not be a deliberate malicious action by the industry—a new fishing technology like deep-sea fishing nets may increase fishing efficiency and reduce costs. However, the oscillations have real human impacts—due to the long times it takes to replenish a fish population, this might introduce cycles extending over decades, which in turn affect jobs and communities.

Outcome 3: Overfishing to Extinction

Here, the industry harvests the fish population beyond the point of replenishment. When there are too few fish in the sea, they don’t find each other and they can’t reproduce enough to overcome the fishing rate.

What happens is a wipeout of the fish population, which in turn destroys the fishing industry. Without careful management, the industry may, without knowing it, drive itself out of business.

A few factors make extinction more likely:

- External factors like pollution may harm the population’s reproduction rate. This raises the critical point below which replenishment is no longer possible.

- If there are long delays in recognizing a dwindling resource stock, and in slowing capital growth in response, the capital stock can grow too quickly and overwhelm the resource.

Questions to Understand a System

We’ve seen a series of system models and connected them to real-life situations. You might now see the benefit of systems-level thinking—it can clarify a situation and how it is likely to unfold in the future.

As you try to view the world with a systems lens, these three lines of questioning will help you more accurately understand the system:

1. What are the driving factors of the system? Would the driving factors affect the system as described?

- Is the model good? Does it reflect the actual dynamics of the system?

2. What is causing the driving factors?

- Are there feedback loops at work? Surely the cause influences the effect, but does the effect influence the cause?

- What other factors external to the system affect the driving factors?

- For a population’s birth rate and death rate, might economics, social trends, and medical technology be involved?

3. How likely are the driving factors to unfold as predicted?

- This is guessing the future, which is inherently inaccurate. But you can weigh the likelihood of different possibilities, and simulate the future in those different scenarios.

Part 2: Understanding Systems | Chapter 3: Why Systems Perform Well

Systems are capable of accomplishing their purposes remarkably well. They can persist for long periods without any particular oversight, and they can survive changes in the environment remarkably well. Why is that?

Strong systems have three properties:

- Resilience: the ability to bounce back after being stressed

- Self-organization: the ability to make itself more complex

- Hierarchy: the arrangement of a system into layers of systems and subsystems

We’ll discuss each one in more detail.

Resilience

A resilient system is able to persist after being stressed by a perturbation.

- The human body avoids disease by foreign agents, repairs itself after injury, and survives in a wide range of temperatures and food conditions.

- An economy can work its way out of a grave unexpected event and out of recessions.

Think of resilience as the range of conditions in which a system can perform normally. The wider the range of conditions, the more resilient the system.

Resilience doesn’t mean that the behavior is static or a flat line. Dynamic systems, like the year-long oscillation of a tree growing in spring and shedding leaves in fall, can be resilient as well. Resilience just means that the normal behavior of a system persists through perturbations.

What Creates Resilience?

The stability of resilience comes from feedback loops that can exist at different layers of abstraction:

- There are feedback loops at the baseline level that restore a system, like what we’ve talked about. To increase resilience, there may be multiple feedback loops that serve redundant purposes and can substitute for one another. They may operate through different mechanisms and different time scales.

- Above the baseline loops, there are feedback loops that restore other feedback loops—consider these meta-feedback loops.

- Even further, there are meta-meta feedback loops that create better meta-loops and feedback loops.

To understand this, consider the human again. The body has baseline feedback loops that regulate our breathing and injury repair without our thinking about it. Above this, we also have a brain that can consciously regulate our behavior, discover drugs that influence our bodily feedback loops, and design economies that help us discover drugs. The human body is thus a remarkably resilient system.

Problems from Ignoring Resilience

At times, we design systems for goals other than resilience. Commonly, we optimize for productivity or efficiency. This can make the system very brittle—it narrows the range of conditions in which the system can operate normally. Minor perturbations can knock the system out of balance.

Examples include:

- Modern agriculture, which has biologically selected for cows that produce more milk than is natural. To compound the problem, farmers then apply growth hormones to stimulate milk production, which further diverts the body’s resources from health. The cow has become less resilient, is more susceptible to being sick, and thus requires antibiotics to ward off infections.

- Just-in-time manufacturing, which brings parts to the manufacturer just when it is needed. This is efficient because it reduces inventory, but it makes the system more vulnerable to shocks in the supply chain.

- Large organizations can lose their ability to respond to changes in the marketplace because the information and decisions have to struggle through too many layers.

Beware of designing a system that is brittle and cannot heal itself after a perturbation.

Self-Organization

Self-organization means that the system is able to make itself more complex. This is useful because the system can diversify, adapt, and improve itself.

Our world’s biology is a self-organizing system. Billions of years ago, a soup of chemicals in water formed a cellular organism, which then formed multicellular organisms, and eventually into thinking, talking humans.

What Creates Self-Organization?

While self-organization can lead to very complex behaviors, its cause doesn’t need to be complex. In fact, a few simple rules can give rise to very complex behavior.

(Shortform examples: The biological development described above occurred through the combination of a few simple rules:

- Life is encoded in DNA, which gives rise to the proteins and biochemical systems that allow an organism to function.

- Mutations in DNA create variations that change the organism’s ability to survive; the organism passes these mutations to its offspring.

- Through natural selection, the organisms that can reproduce more successfully do so, thus driving evolution of the population.

From these rules, a unicellular organism can ultimately lead to humans.

Similarly, the economy, a complex system, largely works with a few simple rules, such as:

- Use money as a medium of exchange

- Allow people to benefit their own self-interest by producing things of value to other people

Simple rules like these can allow an apple farmer to trade with a furniture maker, and ultimately give rise to a complex economy, consisting of a vast web of relationships that functions productively without any global supervisor.)

Problems from Ignoring Self-Organization

Self-organization produces unexpected variations. It requires experimentation, and tolerance of whole new ways of doing things.

Some organizations quash self-organization, possibly because they optimize toward performance and seek homogeneity, or because they’re afraid of threats to stability. This can explain why some companies reduce their workforces to machines that follow basic instructions and suppress disagreement.

Suppressing self-organization can weaken the resilience of a system and prevent it from adapting to new situations.

Hierarchy

In a hierarchy, subsystems are grouped under a larger system.

There are many nested layers in the hierarchy of our world. Let’s take you as an example:

- The individual cells that make up your body are highly complex systems in their own right.

- Together, the cells work together as organs, forming the larger system of the human organism.

- You work as part of a larger system of multiple people, such as a family, a company, and your local community.

- These systems of people form larger systems such as cities, states, and nations. And, altogether, these form a worldwide human system.

As systems self-organize and increase their complexity, they tend to generate hierarchies naturally. For example:

- A single business founder has too much work, so she hires support staff and oversees them.

- A single cell developed into multicellular organisms, with each cell having specialized roles within the organism.

Why Hierarchy?

In an efficient hierarchy, the subsystems work well more or less independently, while serving the needs of the larger system. The larger system’s role is to coordinate between the subsystems and help the subsystems perform better.

The arrangement of a complex system into a hierarchy improves efficiency. Each subsystem can take care of itself internally, without needing heavy coordination with other subsystems or the larger system.

This arrangement reduces the information that the subsystem needs to operate, preventing information overload. It also reduces delays and minimizes the need for coordination.

For example:

- Your pancreas senses blood glucose and secretes insulin, without needing to ask your legs or your brain whether it’s ok.

- (Shortform note: In a market economy, people can sell and produce goods on the marketplace, largely without needing to coordinate with other subsystems or authorities. Imagine if, before selling your goods in a yard sale, you needed to contact the central government for permission, contact another bureaucracy for pricing, then contact other households who were also planning yard sales.)

Problems from Ignoring Hierarchy

In a hierarchy, both the subsystems and the larger system have their role. If either deviates from the role, the system’s performance suffers.

The subsystems work to support the needs of the larger system. If the subsystem optimizes for itself and neglects the larger system, the whole system can fail. For example:

- Individual football players are subsystems within the larger system of the overall team. If a single football player cares more about individual glory and not the victory of the team, he may run plays in a way that causes the team to lose.

- A single cell in a body can turn cancerous, optimizing for its own growth at the expense of the larger human system.