1-Page Summary

In Tiny Habits, Stanford behavioral scientist BJ Fogg argues that the best way to change behavior is to start small. Fogg encourages us to drop any moral judgment about “good” and “bad” habits and view our behavior scientifically, using specific behavior design skills to engineer lasting changes.

The Fogg Behavior Model

The Fogg Behavior Model is a simple formula that lets you pick apart the components of any particular behavior. This formula is B = MAP, where B is Behavior, M is Motivation, A is Ability, and P is Prompt. A behavior only happens when all three MAP variables are present at the same time.

Let’s look at each of these components in turn:

- Motivation is less important than most of us think. It’s unreliable, it’s hard to budge, and some of our motivations are unconscious or conflict with one another. On top of that, motivation can be especially difficult to muster when we’re stressed.

- Ability is how easy or difficult it is for us to do the behavior. We can work with Ability in two ways: by improving our own skills, or by making the behavior easier (the central method in Tiny Habits).

- The Prompt is your reminder to do the behavior. Without the Prompt, it doesn’t matter how high your Ability and Motivation are—the behavior won’t happen.

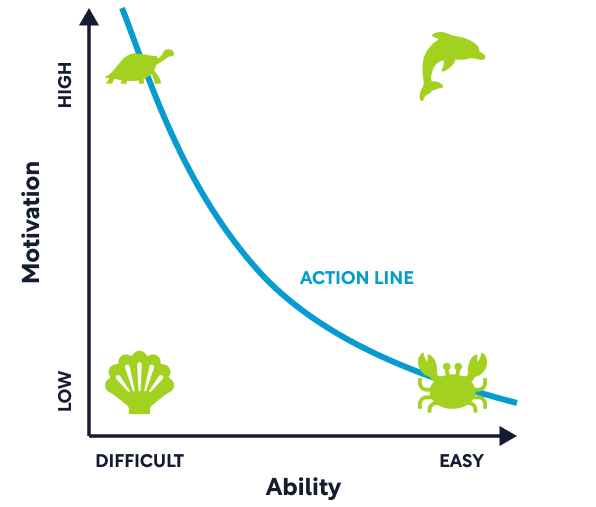

The Action Line is a graphical representation of this model, plotting Motivation on the horizontal axis and Ability on the vertical axis. In the graph below, the blue star is a behavior that’s very easy to do and for which you have a moderate level of motivation. It sits far above the action line, so when you’re exposed to the prompt you’ll have no problems doing this behavior. The green star is a behavior that’s much more difficult. Though you have almost as much motivation as for the blue star behavior, the high level of difficulty means that even with a well-designed prompt you won’t get above the Action Line and manage to do the behavior.

The Behavior Design Process

The Behavior Design process is the method we use to convert the Fogg Behavior Model into a new habit. It consists of seven steps, which we move through one by one to convert a vague aspiration into a lasting habit.

1. Pinpoint your exact aspiration or outcome. Get very clear on what exactly you want to achieve. The clearer your aspiration is, the more likely your new habit is to succeed.

For example, let’s say your aspiration is to be less tired during the day. But when you really think about the root of the problem, you might realize that a better aspiration is “Get better sleep.” You use this as the starting point for your design.

2. Brainstorm possible behavioral solutions. Write your aspiration in the middle of a page or whiteboard and put a circle around it. How many different specific behaviors can you come up with that might help you achieve this? Be wacky and creative as well as logical and realistic, and aim to write down at least 20 different behaviors. When you’re finished brainstorming, you’ll have a diverse Swarm of Behaviors (“Swarm of Bs”) that you can use in the next step.

For example, let’s continue with the aspiration “Get better sleep.” You might come up with the following behaviors: “Buy a blackout curtain,” “Try a white noise machine,” “Move to somewhere quieter,” “Try aromatherapy,” “Stop napping during the day,” and so on. When you have your initial set of behaviors, look over them and make sure they’re as specific as possible. For example, you could change “Try aromatherapy” to “Take a hot lavender-scented bath.”

3. Identify the Golden Behaviors. To find your Golden Behaviors, you engage in a process called Focus Mapping. To Focus Map, write your Swarm of Bs on individual index cards. Then draw up some axes as shown here: The vertical axis shows the impact of the behavior, while the horizontal axis shows its feasibility.

First, think only about the vertical axis. For each of the cards, ask yourself: Will this be an efficient way to achieve my aspiration? If the behavior is likely to be high-impact, put it near the top. If it’s not, put it near the bottom.

Then think only about the horizontal axis. For each of the cards, ask yourself: Is this realistic? Do I really want to do this? Move the cards to the left or right based on your answer.

You should end up with a few behaviors in the top right-hand quadrant. These are your Golden Behaviors. For example, you might find that “take a hot lavender-scented bath” is both high-impact (lavender and baths have both been shown to positively affect sleep) and feasible (you have a bathtub, you enjoy using it, and you often have some free time in the evening).

Choose a small number of these (one to five) and focus only on them in Steps 4 to 7. If you don’t have any behaviors in that quadrant, create another Swarm of Bs and try again.

4. Find the tiny version. The core of Tiny Habits is making any new habits so small that they’re completely unintimidating. By doing this, you’re protecting them as much as possible from the vagaries of motivation. This often results in a behavior that’s so tiny that it seems absurd: turning on the stovetop burner, putting on your walking shoes, flossing one tooth. This may feel silly, but go with it. Tiny actions can be surprisingly powerful.

There are two ways you can create a tiny version of a behavior. You can figure out what the very first step (Starter Step) of the behavior is and go with that. Or you can do a part of the behavior for a very short time (Scaled-Back Version). For example, let’s say that “take a hot lavender-scented bath” is one of your Golden Behaviors. A Starter Step for this behavior might be taking out the lavender oil and unscrewing the cap. A Scaled-Back Version might be running some hot water in the sink, adding a few drops of lavender oil, and inhaling the scent for a couple of minutes.

5. Choose your prompt. Remember, no behavior happens without a prompt. Once you’ve identified which tiny behavior you want to introduce into your life, you need to find a good prompt to remind you to do it. You can tie this prompt to yourself (some kind of internal emotional or physical cue), your context, or an action in a pre-existing routine. Action-based prompts are special in Tiny Habits. They’re called Anchors.

For example, a person-based prompt for the lavender bath might be “when I feel tired at night.” For a context-based prompt, you could leave the lavender oil bottle in the bathroom where you can see it. And for an Anchor, you could decide to do your tiny habit right after you’ve put the kids to bed.

6. Celebrate. Celebration is incredibly important in Tiny Habits. In fact, celebrating well is a habit in its own right, one that we can cultivate to make us happier, more resilient, and nicer to be around. Experiment to find some celebrations that work for you. Aim for celebrations that make you feel “Shine”: an authentic sense of accomplishment and happiness. Perhaps your best route to Shine is raising your fists in victory, or humming a snatch of the theme song from Rocky, or nodding your head quietly to yourself in affirmation. A genuine celebration immediately after you do your habit helps your brain to encode and automatize the behavior sequence, so it’s important not to skip this step.

For example, a good celebration for the tiny behavior of unscrewing the cap on the lavender oil bottle might be smiling wide, yawning, and stretching luxuriously.

7. Repeat, refine, and upgrade. The Behavior Design process is like an experiment. Play around with the sequence and modify things as you go. If your tiny habit isn’t working, go back to your Swarm of Bs and pick another one. If the prompt you’ve chosen is unreliable or if you’ve become good at ignoring it, pick another one. Remember that if a new habit fails, the problem isn’t you—it’s how the habit has been designed.

When repeating, refining, and upgrading, you gradually expand the Tiny Habit to make it less tiny. You allow it to grow naturally, not pushing yourself to build it up too fast or getting down on yourself if you mess up. In time, your tiny habit of unscrewing the cap on the lavender oil bottle may evolve into a luxurious hour-long bubble bath. Sometimes, of course, you won’t have time for this, and sometimes you won’t have the motivation. The important thing is to keep the habit alive by unscrewing that bottle cap every day.

Shedding Bad Habits

Though Tiny Habits wasn’t initially designed to help people get rid of bad habits, you can also apply the Fogg Behavior Model and the Behavior Design process to “reverse engineer” habits out of your life. This doesn’t apply to serious addictions, however—Tiny Habits aren’t a substitute for professional help.

To begin with, we can classify habits into three types: Uphill Habits, which we have to work to keep going (going to the gym every day, getting up early, cleaning the kitchen), Downhill Habits, which we have to work to stop doing (scrolling through social media, sleeping through the alarm, eating fast food), and Freefall Habits, which are almost impossible to stop (serious addictions). When applying Tiny Habits to bad habits, we’re talking about the Downhill Habits.

How to Eliminate Downhill Habits

We usually use the word “break” when talking about stopping a bad habit, but this metaphor doesn’t work in the Tiny Habits context. A better metaphor is a complicated snarl of knots in a string. We’re unraveling this tangle one knot at a time. When approaching a tangle like this, you work on the easiest, most accessible part first.

To eliminate an existing habit, apply the Fogg Behavior Model and the Behavior Design process in reverse.

If the behavior is already happening, there must be a regular convergence of Motivation, Ability, and Prompt in your daily routine. Can you disrupt one or more of these factors to stop the behavior from happening?

- Can you reduce your Motivation to do the behavior? (This is hardest; leave it until last.)

- Can you reduce your Ability to do the behavior? (This is a good bet. Think about ways to make the activity physically harder, mentally harder, more expensive, and more time-consuming.)

- Can you get rid of the Prompt, or at least reduce its effectiveness? (Perhaps you can stop walking down the junk food aisle at the supermarket, or silence your phone, or delete a social media app.)

Apply the Behavior Design steps. Go through the seven steps of Behavior Design to design away the existing behavior. Perhaps the overall problem is “Eating junk food.” Create a Swarm of current Bs that feed the general problem, for example: “Eating a chocolate muffin in my morning break,” “Ordering hamburgers when I’m too tired to cook,” “Eating ice cream when I’m feeling down,” and so on. Which of these will be easiest to stop? Focus on that one first. See if you can manipulate the Ability and Prompt dimensions to design it away and introduce a healthier version in its place. And don’t forget to celebrate when you do your new, healthier habit.

When the first habit has fallen away, pick the second-easiest knot to untangle, and patiently work through the rest of them one by one. If you’re struggling, it may help to:

- Substitute a new habit for the old one. Remap the prompt so that it prompts you to do another behavior. Ideally, this behavior should be both easier and more motivating than the one you’re trying to get rid of. This is very individual, but someone who loves flowers could, for example, walk past the bakery to the florist and buy a beautiful bunch of flowers.

- Refashion the prompt. Find the prompt that triggers your unwanted behavior and begin to associate it with a new behavior. For example, if you usually open the fridge and grab the first thing you see in there, open the fridge and take three deep breaths instead. Remember to celebrate to lock in this new response.

- Experiment. If it doesn’t work the first time, choose another new behavior and try again. Remember that if you’re shopping for shoes, you usually don’t buy the first pair you try on. Treat finding the substitute behavior like shopping for shoes. If one pair doesn’t fit, keep looking.

- Try a substitute behavior for a limited period (three days; a week) and evaluate after that.

- Get to know your own weak points and take advantage of them. For Fogg, making a behavior physically difficult is the best way to get rid of it.

- If nothing changes, leave the bad habit alone for a while. Go back and sharpen your behavior change skills on other changes. Come back to the habit later.

It’s important to work skillfully with emotions when breaking bad habits. In both cases, we take judgments such as “character” and “weakness” out of the equation. When unraveling old habits, we bypass the feelings of shame and powerlessness that often accompany habits we’d like to stop.

Changing in a Group

When applying the Behavior Design process in a group, first make sure you have some experience applying it to yourself individually. This gives you confidence that you can iron out any bugs as they come along.

When leading group change, you can take either of two roles: the Ringleader or the Ninja. The Ringleader, perhaps a formal authority figure or a family member who’s read Tiny Habits and wants to apply it, openly explains the Fogg Behavior Model and guides the group through the Behavior Design steps. The Ninja, perhaps a team member lower down on the hierarchy or the parent of teenage children, slips Behavior Design principles into general discussions to make sure the change process stays on track.

For example, during Focus Mapping, a Ringleader might draw the Impact and Feasibility axes on a whiteboard and ask group members to come up and arrange Swarm of B index cards. A Ninja might highlight Impact and Feasibility by asking the group, “But how effective will this actually be?” and “Can we really get ourselves to do this?”

The Future of Tiny Habits

Through Tiny Habits, the tiniest changes in our behavior can ripple out and have far-reaching effects, both in our own lives and in the lives of others. The method has worked with hundreds of individuals and families, often leading to profound positive changes in people’s identities or in family dynamics. Large organizations, such as hospitals, are also turning to Fogg for help with problems like employee burnout. He’s found that the method is as effective for groups as it is for individuals, but it needs to be tailored to fit every time.

Fogg envisages a future in which we can use his behavior change methods to tackle complex global problems, one Tiny Habit at a time.

Introduction

In Tiny Habits, Stanford behavioral scientist BJ Fogg argues that the best way to change behavior is to start small. Based on years of experience running a Stanford lab and helping people make changes through monthly Behavior Design Boot Camps, Fogg encourages us to drop any moral judgment about “good” and “bad” habits and view our behavior scientifically, using specific behavior design skills to engineer lasting changes. Through Tiny Habits, Fogg argues that the tiniest changes in our behavior can ripple out and have far-reaching effects, both in our own lives and in the lives of others.

(Shortform note: The book is structured in a series of overlapping circles: Fogg introduces models, methods, and examples of people who have succeeded with the Tiny Habits approach and circles back to them throughout the book, adding more information each time. This summary rearranges the book’s content so that each chapter covers a self-contained principle.)

What Is Behavior Design?

Many of us have tried to make behavior changes in the past. Sometimes we succeed; more often than not, we fail. And we blame ourselves for the failure. But often we are not the problem. We just haven’t designed the change properly.

If you’ve tried and failed to make a change, the Behavior Design approach may be the answer.

The Information-Action Fallacy

Most approaches to behavior change are built on the belief that if people have enough information about why they should make a change, they’ll make it easily and immediately. Fogg calls this the “Information-Action Fallacy” because lasting behavior change is rarely this simple.

We tend to believe that motivation is the only ingredient in behavior change. We think that if we can just build up our motivation enough, we’ll make the change. This leads to self-judgment when we fail. We believe that we failed because we lack self-discipline, or we’re weak, or we lack character. This shame stops us from trying again.

Behavior Design stops you from getting caught in this cycle. In Behavior Design, we look at behavior patterns scientifically and with curiosity. If you fail to introduce a habit, it’s because the habit is badly designed. Simply redesign it and try again.

Positive emotions, rather than negative emotions, are the key. We change best when we feel good. Tiny bursts of celebration help our brains to “wire in” the changes automatically.

The best example of the Behavior Design approach is the Tiny Habits method.

Tiny Habits

Why should we work with tiny habits?

Tiny Habits are:

- Low on time demand. Many of us have full lives and little time to fit in new habits. The idea of a daily ten-second habit is less daunting (and more realistic) than a half-hour one. The typical Tiny Habit takes under 30 seconds. You can do many of the habits suggested in the book in under five seconds. This means you can fit them in easily, no matter how busy you are.

- Effective immediately. A well-designed Tiny Habit is one you can start right now.

- Psychologically safe.

- Wobbles—even faceplants—are part of the process. Babies fall all the time when they’re learning to walk, but it doesn’t hurt much because they’re already close to the ground. If you don’t succeed with your new habit the first time, you’re not a failure: Just stand up, tweak something, and try again.

- Tiny Habits are private. The changes are so small that nobody else needs to know. This means you can operate without any pressure, as well as avoiding You also avoid potential sabotage attempts by others.

- It’s impossible to fail. It’s all an experiment—so if it’s not working, just fiddle with the controls and try again.

- The self-compassion that you practice through Tiny Habits ripples out into your general approach to life.

- Set up for growth. Tiny Habits generate momentum that, over time, helps you accomplish bigger and bigger tasks. You can create an ecosystem of carefully chosen small new habits that together have a big impact.

- Willpower-independent. Motivation, or willpower, isn’t reliable. It comes and goes in waves, so we can’t depend on it to build consistent habits. In Tiny Habits, the target habits are so small that we need very little motivation to do them.

- Fun. The essence of Tiny Habits is play and experimentation. There’s no grim “do or die” mentality—you deliberately focus on activities that you want to do. And all Tiny Habits sequences include an instant celebration, which teaches your brain to do the behavior again.

- Tried and tested. Throughout the book, Fogg gives examples of his own experience creating Tiny Habits. He also includes many anecdotes about the experiences of others who’ve attended his Behavior Design boot camps and online courses.

The Structure of a Tiny Habit

The structure of a Tiny Habit is like a sandwich, with the behavior in the middle. A good mnemonic is ABC:

Anchor: The point in your regular routine that your Tiny Habit will be tied to

Tiny Behavior: The new habit in simple form

Immediate Celebration: Some brief but meaningful way to create positive emotions after you’ve executed your Tiny Habit successfully.

Let’s say you want to introduce the habit of going for a walk after your morning coffee. Your Anchor might be rinsing the cup and setting it down to dry. Your Tiny Behavior might be putting your walking shoes on. And your immediate Celebration might be punching the air and shouting “Yes!”

“Recipes” for Tiny Habits

To capture the experimental feel of Tiny Habits, Fogg translates this sequence into a “recipe.”

1. After… [Anchor]

2. I will… [Tiny Behavior]

3. To celebrate, I will … [Celebration]

Here are some example recipes:

- After I put my coffee cup in the dish drainer, I will put my walking shoes on. Then I will punch the air and shout “Yes!”

- After I brush my teeth, I will floss one tooth. Then I will smile.

If you like, you can write your habit recipes on physical recipe cards for quick reference.

As with any recipe, if it doesn’t turn out well, experiment with the ingredients and proportions and try again.

Terminology

Throughout the book, Fogg refers to three key frameworks he’s invented to codify and communicate his Behavior Design approach. These are the Fogg Behavior Model, the Behavior Design Process, and the PAC Person.

The Fogg Behavior Model is a way of thinking about behavior. It sees all behavior as directly caused by a combination of three things: Motivation, Ability, and Prompt. The formula for this model is B = MAP. You’ll learn about the Fogg Behavioral Model in Chapter 1.

The Behavior Design Process is a method for behavior change based on the Fogg Behavior Model. The method has seven steps that are divided into three broad phases: Selection (Steps 1-3), Design (Steps 4 and 5), and Practice (Steps 6 and 7). You’ll find information about Selection in Chapter 2, Design in Chapter 3, and Practice in Chapter 4.

The PAC Person is a heuristic for thinking about the resources available when executing a behavior. It shows us that there are three main types of resources available at any given moment:

- Person (qualities relating to the individual);

- Action (qualities relating to the action being performed); and

- Context (qualities relating to the environment the individual is in).

For example, we can use the PAC Person to talk about where motivation comes from. The person components are your intrinsic enjoyment of the activity and how interested you are in doing it. The action components are any rewards or punishments for doing the activity. And the context components are any social influences on the activity, as well as conducive and non-conducive physical environments.

Tiny Habits is a name that refers to the entire set of processes and models, as well as to the scaled-down habits that are the centerpiece of Fogg’s approach. A Habiteer is anyone who practices the Tiny Habits method.

Because the Behavior Model and the PAC Person have some acronym letters in common (P for Prompt and Person; A for Ability and Action), references to these acronyms can occasionally be confusing. Wherever there’s any ambiguity, we’ll remind you of what each acronym letter means in context.

The Fogg Behavior Maxims

The two Fogg Behavior Maxims serve as Fogg’s reference point with his work training others in Tiny Habits. If you’re helping people to design their own behavior in the future and get tangled up in all of the steps and stages, referring back to these maxims will simplify things.

Behavior Maxim #1: Help people do something they already want to do.

Behavior Maxim #2: Help people feel successful.

For now, you’re focusing on yourself. To apply the maxims, rephrase them maxims as questions to ask yourself throughout the process: “Does this help me do something I already want to do?” and “Does this help me feel successful?”

Example: The Maui Habit

Fogg invented this habit in Maui and has taught it to thousands of people at his boot camps. It’s a good way to start the day on a positive note.

Recipe:

After my feet touch the floor in the morning,

I will say, “It’s going to be a great day,” while feeling confident and optimistic.

To celebrate, I will smile.

Try incorporating this habit into your morning routine. Experiment with the recipe that works best for you.

You can change the anchor: “When I open my eyes…” or “When I look in the mirror…”

Adapt the habit to your circumstances. You don’t want this to feel fake. So if you know you have a challenging day ahead, you can use uncertain intonation and say, “Well, something great is going to happen today…”

In Chapter 1 of this summary, we’ll break down the Fogg Behavior Model, considering Motivation, Ability, and Prompts in detail. In Chapters 2 to 4, we’ll look at how this model is applied in the Behavior Design process when focusing on one person (yourself). While Chapters 2 to 4 chapters talk about how to build in new habits, in Chapter 5 we’ll learn how to use Behavior Design to get rid of habits that aren’t serving us. In Chapter 6, we’ll broaden our application of Behavior Design past the individual and learn a range of strategies for changing as a group. Chapter 7, the Conclusion, revisits the Fogg Behavior Maxims and shows how we can apply them to improve people’s lives on a large scale.

Exercise: Choose a Habit to Work On

Think about an area of your life that might benefit from the Tiny Habits approach.

What’s the habit that you’d most like to cultivate in your life right now? How can you create a Tiny Habit recipe for this behavior?

Recipe:

- After… [Anchor]

- I will… [Tiny Behavior]

- To celebrate, I will … [Celebration]

Exercise: Try the Maui Habit

Experiment with the Maui Habit, a great way to start or continue the day on a positive note.

At this moment, how are you feeling? List any emotions or thoughts that come up.

Close your eyes and say, “It’s going to be a great day,” feeling genuinely confident and optimistic as you say it.

How do you feel now? What’s changed?

How might you integrate this habit into your daily life? List some possible Anchors for the habit. (For example: When my feet touch the ground in the morning; when I look in the mirror; the first time I walk into my office every day.)

Chapter 1: The Fogg Behavior Model

The Fogg Behavior Model is a simple way of breaking down the components of a particular behavior. This helps us to understand the causes of the behavior, which in turn lets us pinpoint any problem elements and address them directly.

In this chapter, we’ll look at each component of the Fogg Behavior Model in turn, and we’ll learn about the Action Line, a way of visualizing how the Fogg Behavior Model applies to any given behavior. We’ll also discuss why motivation isn’t the best starting point for building lasting new habits and introduce some alternative, more reliable jumping-off points.

Fogg Behavior Model: B = M A P

Behavior (B): The specific action we’re considering.

This formula applies to any human behavior, from dropping dirty clothes on the floor to climbing Mount Everest. This means that the model applies regardless of culture or environment, and regardless of the ease or difficulty of the behavior.

Motivation (M): Your desire to execute the behavior.

Motivation fluctuates wildly from day to day and from behavior to behavior. Here, we’re talking about the motivation you have at the exact time you’ll execute a given instance of the behavior.

Ability (A): Your capacity to execute the behavior.

This includes two main dimensions: your own skills related to this behavior, and the difficulty of the behavior itself.

Prompt (P): The cue that reminds you to execute the behavior.

While motivation and ability can vary, prompts are binary. You either notice them or you don’t.

For a behavior to occur, M, A, and P must all be present simultaneously. If one is missing, the behavior won’t happen.

The model builds in individual differences. M, A, and P for a given behavior vary widely between individuals, and will even be different for the same individual in different contexts and at different times. Experimenting with all of these variables will teach you the best way to configure your new habits.

Note that this model does not model the general characteristics of a behavior. Instead, it applies to one instance of the behavior at a given point in time.

For example, let’s say you want to introduce the behavior of going to the gym. Your motivation to do this will vary from moment to moment. Your ability will also vary: Sometimes it’s easier to go to the gym (perhaps when you have less going on at work) and sometimes it’s more difficult. And at any point in time, you may or may not have a prompt reminding you to go to the gym.

The model doesn’t help us much with the general idea of going to the gym, because there’s so much variation in M, A, and P. But if we think instead about going to the gym right now, the motivation and prompt components are more fixed. Now we can apply the model with more accuracy.

Tiny Habits uses the Fogg Behavior Model as its basis.

The Action Line

By looking at the “Action Line,” we can work out whether or not a behavior will be performed.

Let’s plot Motivation and Ability as the axes on a graph. The Action Line is a curve marking the threshold at which an action will be performed.

In this graph, the blue star is a behavior that’s very easy to do and for which you have a moderate level of motivation. It sits far above the action line, so when you’re exposed to the prompt you’ll have no problems doing this behavior. The green star is a behavior that’s much more difficult. Though you have almost as much motivation as for the blue star behavior, the high level of difficulty means that even with a well-designed prompt you won’t get above the Action Line and manage to do the behavior.

Ability and Motivation are complementary. If you have more ability (or if the action is easier), you need less motivation to get over the Action Line. If you have less ability, you’ll need more motivation to get over the Action Line. This is why if you’re extremely motivated to do something but the activity is very difficult (such as lifting a car to save someone pinned underneath), you still have a chance of getting over the Action Line.

If a behavior is currently below the Action Line, how can you lift it above the curve? You can target any of M (Motivation), A (Action), or P (Prompt).

If motivation isn’t going to change, target A or P.

For example, housework in a shared household is a common point of contention. Here’s one problem that arose in Fogg’s household. His partner wanted him to wipe down the shower every time he used it, but the habit just wasn’t sticking.

Fogg analyzed M, A, and P. There was motivation (a shared desire for a clean shower) and a clear prompt (turning off the water), but the behavior wasn’t happening. Why? He realized that he simply didn’t understand what “wipe down” meant in this context. With what? How?

So he asked his partner to show him how to do it. After his partner had demonstrated exactly what to do, Fogg’s ability increased, pushing the behavior over the Action Line.

The Fogg Behavior Model is about design, not about character judgment. Notice that there’s no “self-discipline” or “moral fortitude” axis.

Example: Katie’s social media habit

We can see the Action Line at work in the situation of Katie, a successful executive. Katie had one troublesome habit that consistently fell above the Action Line: scrolling through social media on her phone after her alarm went off at 4:30 am, not leaving her enough time to go to the gym.

To conquer this social media habit, Katie examined M, A, and P in turn.

Her motivation was to stay in touch with family and friends. Knowing that this motivation would be hard to change, she moved on to Ability.

Scrolling through social media in bed is incredibly easy, so there were opportunities here to make it harder. Katie experimented with several options, eventually finding that keeping her phone in the kitchen overnight made the behavior hard enough that she wasn’t tempted.

As the prompt for this behavior was the phone itself, putting the phone in the kitchen also removed the prompt. Katie bought an alarm clock for her bedroom, which woke her up without the temptation of social media.

After this adjustment, Katie successfully banished the bad habit and started going to the gym immediately after she woke up.

Katie’s experience exemplifies many of the specific Behavior Design techniques that we’ll learn about in more detail in later chapters.

Breaking Down the Fogg Behavior Model

Recall that the structure of the Fogg Behavior Model is B = MAP. Let’s consider Behavior, Motivation, Ability, and Prompt in turn.

What Is a Behavior?

Most people confuse behaviors, aspirations, and outcomes.

An aspiration is a desire for something abstract (become a lawyer; get rich). An outcome is similar to an aspiration, but more concrete (pass the bar exam; earn 30% more in commissions. A behavior is much more specific: it’s something you can do at a given time (open a law textbook; make a sales call).

We don’t use the word “goal” in Behavior Design because it isn’t clearly defined—it could apply to any of the above.

Think of your aspiration as the top of a cliff face you’re climbing. Your behaviors are like the jutting pieces of rock you hold onto to pull yourself higher. There’s no prescribed way to climb the rock—you choose the path—but the behaviors that support you should be solid and dependable.

You can disambiguate between behaviors and aspirations or outcomes with one question: Can I do it at a given time (for example, right now)?

Fogg encountered this common confusion between behaviors and aspirations in his consulting work at a bank. The bank had introduced a new initiative to encourage people to put aside a $500 emergency fund. He asked the staff, “What behavior do you want people to do?” They answered, “Save $500.” He replied, “OK, all of you save $500 right now.” This made them realize that they needed to be more specific in their suggestions—to target the “how” and not the “why.”

The “how” is the step that most people overlook. The strength of Behavior Design is that it makes “how” the focus. Think of Marie Kondo’s smash hit books on tidying up. These books don’t focus on why you should be tidying up. They take you through the concrete steps of how to do it. (Shortform note: Read our summary of Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up.)

M: Motivation

Motivation is your desire to execute a specific action (such as “go for a jog”) or category of actions (such as “do exercise”).

You can think about motivation as a force that draws you toward certain actions and pushes you away from others. A desire for love, for example, pulls you toward a relationship. An aversion to physical exertion pushes you away from strenuous exercise.

We can sort different motivations according to the PAC (Person, Action, Context) dimensions.

- Person: What does the person want to do?

- Action: What external benefit or reward is available? Are there any punishments for doing or not doing the behavior?

- Context: Is the environment (physical and social) helping or hindering?

Motivation can be powerful in helping us with difficult or one-time actions (more on this later), but we shouldn’t rely on it for long-term behavior change. Here’s why.

Motivation Is Complicated

Motivation is unreliable. Motivation is like that one friend you have who’s the life of the party. She’s terrific to have a few drinks with, but would you rely on her to pick you up from the airport?

Motivation comes in waves. It ebbs and flows on large and small timescales. Something that feels like no big deal when you’re surfing the motivation wave can become insurmountable when you’re wallowing in the trough. Motivation can vary:

- Daily—Willpower is known to be highest in the morning.

- Seasonally—Weight Watchers has consistent peaks and troughs in their signups throughout the year (peaks in January and after Labor Day; troughs in November and December in the lead-up to food-saturated holidays).

- Depending on the circumstances—If you eat lunch at 1 pm, you’ll be more tempted by a pizza at 12:30 than at 1:30.

Some motivations are more consistent, but these are much less common. Examples of these might be wanting to spend more time with your pet or wanting your child to succeed.

Competing motivations can pull us in opposite directions. You may want to reduce the sugar in your diet, but you may also really want that chocolate chip cookie.

Motivation can be opaque. Often we don’t have a clear understanding of our own motivations. This means that subconscious motivations can rise up out of nowhere and sabotage our efforts.

Working With Motivation

To work intelligently with motivation, we need to do the following.

Avoid Abstractions

Often we try to motivate ourselves with abstract aspirations: “eat healthier,” “save more money,” “reduce stress.” But these are not specific behaviors. Dreams and aspirations are not bad things. We need them as human beings. But to turn them into habits, we need the extra “How?” step.

Aiming to motivate specific behaviors is the key. We can substitute the above aspirations with “eat an apple after lunch every day,” “set up an automatic direct debit of $50 per month to a savings account,” and “meditate for ten minutes every day.”

Understand That Motivation Is Not the Key to Long-Term Change

Motivation is only one of three “ways in” to a new habit (the others are Ability and Prompt), and it’s usually the most difficult. Think about the following three ways to enter a building. Ability is like opening the door and walking in. Prompt is like driving into the parking lot. And Motivation is like parachuting down, landing on the roof, and picking the lock on the rooftop door.

Motivation alone is not enough. Suppose someone offers you a million dollars to lose ten pounds right now. There’s no way you can do this, even if your motivation is off the charts. Focus on A and P first.

In Tiny Habits, Motivation Is Already Present

- Through Focus Mapping (more on this in Chapter 2), you choose only habits that you’re already motivated to do.

- This makes Tiny Habits different from other approaches.

- In Tiny Habits, “I want to” is more important than “I should.”

A: Ability

Now that we’ve considered M (Motivation), let’s turn to the next variable in the B = MAP formula: A (Ability).

The best way to make a change is to keep things simple. But this isn’t usually how we approach change. We want to go “all in” on new changes, turn our lives upside down, and see fast results.

Sometimes bold action is necessary and helpful. For example, you might quit your job to pursue your dream of running a sub-2:30 marathon. But to create sustainable change in daily life, less is more. If you want to introduce a running habit, start by putting on your running shoes.

The Importance of Simplicity in Business

Most successful companies begin by targeting the Ability dimension: They make our lives easier by offering something very small and specific. This simplicity encourages people to use the product and develop habits that rely on it.

Instagram was founded by Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger. (Krieger is a former student of Fogg’s.) They analyzed Burbn, an unsuccessful location-sharing app, and found that the feature users liked most was photo sharing.

This focus on photo sharing targeted a Golden Behavior: something that people were already motivated to do. Systrom and Krieger built a new app around this Golden Behavior, simplifying the process into a short sequence of clicks. By making photo uploads so easy, they targeted the Ability component of B = MAP, pushing photo-sharing behavior on the app well above the Action Line. They only added more features after their users had a well-established habit.

Now Instagram has over a billion users and is worth over $100 billion. Businesses that offer complex features right from the start often fail—so if you’re offering a new product or service, aim for simplicity first.

Example: Sarika and the Stovetop Burner

One person who manipulated Ability with great success was Sarika, a project manager in Bangalore. Though successful at work, Sarika had a lot going on behind the scenes: She had bipolar disorder, and she was trying to come off her medication and manage the symptoms with a combination of healthy eating, exercise, therapy, and meditation. Developing and maintaining a routine was especially important, because any variations in the routine would act as early warning signs for episodes of mania or depression.

Unfortunately, Sarika found routine extremely difficult. The only thing that worked was to create little toeholds via the Tiny Habits method.

She introduced the habit of turning the stove burner on when she went into the kitchen in the morning.

She introduced the habit of putting her meditation cushion in the middle of the room, sitting on it, and taking three breaths.

She introduced the habit of putting out her yoga mat and stretching for thirty seconds.

These Tiny Habits grew into cooking herself breakfast, meditating consistently, and exercising. On days when she reverted to only turning on the burner or only doing thirty seconds of stretching, she didn’t beat up on herself—she celebrated because she had kept her habit alive. In time, Sarika noticed that practicing Tiny Habits had made her more emotionally resilient, probably because of the non-judgmental attitude toward stumbles and challenges.

When you target Ability, you find a way to make the activity easier for yourself. You can use the PAC (Person, Action, Context) dimensions for this:

- Improve your skills (P);

- Make the activity easier (A); or

- Design your environment to boost your chances of doing the activity (C).

We’ll cover these more in Step 4 of the Behavior Design sequence (“Find the Tiny Version”) in the next chapter.

P: Prompt

With M (Motivation) and A (Ability) clear, let’s turn to P: the Prompt.

The Prompt is the immediate trigger for a behavior. Without the prompt, the behavior won’t occur.

Prompts are ubiquitous in our daily lives. If we refer back to the PAC Person, we can see that prompts come from three sources:

- Person: prompts that originate in your own body or mind. Feeling hungry and suddenly remembering that you need to call your grandmother are person prompts.

- Action: prompts related to the activity you’ve just finished doing. Stepping out of the shower and then immediately drying off, or sitting down at the computer and immediately checking your email, are action prompts.

- Context: prompts that come from your environment. Your pet reminding you it’s time for their dinner, a text message notification sound on your phone, and a red light when you’re driving are all context prompts.

Prompts can be either natural (bright sun comes out and you put on your sunglasses) or designed (you hear a smoke alarm and evacuate the building).

Prompts Have a Binary Structure

Prompts are binary (either you respond to them or you don’t). This contrasts with ability and motivation, which both vary within a wide range.

A prompt is like a switch: Without a well-timed prompt, there is no behavior, even if your ability and motivation are both high.

These days, our prompt landscape is very cluttered, and it’s easy to ignore most prompts by default. If you want to make sure you’ll pay attention to a prompt when it comes around, the design of the prompt is key.

We’ll talk about the practical side of prompts—selecting and implementing them—in Chapter 3.

Exercise: Rethink Motivation

Dethrone motivation as the go-to solution for behavior change.

What habit have you tried to create (or break) in the past by relying too much on willpower or motivation?

Why was relying on motivation a problem in this case? (Did your motivation ebb and flow? Did you have conflicting motivations? Were your goals too abstract to be motivating?)

Given the information in this chapter, what other approaches might you try? (For example, could you make the activity easier? Could you change the prompt?)

Exercise: Map a Behavior on the Action Line

Learn to work with Motivation, Ability, and the Action Line.

On a piece of paper, draw a vertical axis for Motivation and a horizontal axis for Ability. Now draw in the Action line curve.

Think of one new habit you’d like to create and one unhelpful habit you’d like to break. Plot both behaviors. Where does each sit in relation to the Action Line? Are they close to the Action Line (easier to change) or far away?

Take the new habit you’d like to create. List some ways you could manipulate ability to lift this above the Action Line.

Chapter 2: Behavior Design Phase 1—Selection

In this chapter, we’ll start applying the Fogg Behavior Model, which we discussed in Chapter 1, to the following practical question: How do we build positive new habits into our lives? The complete Behavior Design process consists of seven steps divided into three broad phases: Selection, Design, and Practice.

Steps in Behavior Design

The seven steps in Behavior Design are as follows:

Selection

1. Pinpoint your exact aspiration or outcome

2. Brainstorm possible behavioral solutions

3. Identify the Golden Behaviors

Design

Find the tiny version

Choose your prompt

Practice

Celebrate

Repeat, refine, and upgrade

In this chapter, we’ll discuss Phase 1 (Selection), consisting of Steps 1 to 3. We’ll talk about Phases 2 and 3 in later chapters.

1. Pinpoint Your Exact Aspiration or Outcome

What exactly are you aiming to achieve?

Often our aspirations are vaguer than we realize. The clearer the aspiration, the more targeted your behavior design can be.

Sometimes we misfire when creating aspirations. It helps to consider carefully where we really want to end up. For example, if your aspiration is to cut back on caffeine, what exactly are you aiming for? To feel less anxious? To sleep better? To manage blood pressure? Would it be more efficient to approach these targets in other ways?

You can use both aspirations and outcomes as a starting point. However, aspirations are better to start with because they’re usually less rigid—and therefore less daunting—than outcomes.

2. Brainstorm Possible Behavioral Solutions

Once your aspiration or outcome is clear, come up with as many behaviors as you can that might help you to get there. The goal here is volume, not practicality.

Don’t go into detail or get stuck on elaborating any of your ideas. As soon as you’ve generated an idea, tell yourself, “OK, and what else?” Aim to create a “Swarm of Behaviors” (“Swarm of Bs”).

Use the Magic Wanding approach. If you had magical powers and infinite resources, what would you do? Move to a tropical island? Get a job that pays double? Hire a live-in housekeeper? Let your optimism do the talking, and be creative. The Swarm of Bs should be as diverse as you can make it. There should always be some answers that surprise you alongside the obvious, logical ones.

It may help to generate ideas under three categories: one-off behaviors (for example, deleting a social media app from your phone or buying a set of high-quality kitchen knives for food prep); fresh habits to cultivate; and unhelpful habits to drop.

After you have your Swarm of Bs, check that the Bs are well-defined. Take any that are fuzzy or poorly defined (for example, “snack on fruit once a day”) and see if you can make them clearer and crisper: “Eat an apple every day after lunch.”

If you’re not sure how to define your behavior clearly, ask yourself three questions.

- Is it a one-off behavior, or will you repeat it?

- What exactly will you be doing? (Remember the advice from the previous chapter on the difference between behaviors, outcomes, and aspirations. Ask yourself if it’s possible to do the behavior you’ve written down right now or at a particular point in the future.)

- When will the behavior happen?

The “when” question is optional. If there’s no obvious answer, hold off on defining this for now and address it when you work with the prompt (Chapter 3).

3. Identify the Golden Behaviors

Once you have your Swarm of Bs, you’re ready for Focus Mapping.

Here’s how to do Focus Mapping:

1. Write all of your brainstormed behaviors on index cards.

2. On a large flat surface, set up an axis as follows:

3. Arrange cards. Stage 1: Impact. For now, only consider the vertical axis. Take each card individually and ask yourself: Will this be an efficient way to achieve my aspiration?

- If you think it will, put it toward the top of the Impact axis.

- If you don’t think it will, put it toward the bottom.

At the end of Stage 1, all of your index cards should be lined up along the vertical axis, with the most effective at the top and the least effective at the bottom.

4. Arrange cards. Stage 2: Feasibility. Now only consider the horizontal axis. For each card, ask yourself: Is this realistic? Because Tiny Habits is about feeling good and minimizing motivation struggles, a good substitute question is: Do I really want to do this?

Imagine yourself doing the behavior. Does it feel good? Do you feel any resistance? It’s important to listen to even slight feelings of resistance.

5. Look at the top right-hand quadrant. There should be at least two to three behaviors there that feel familiar, easy, and “right.” These are your Golden Behaviors.

If there are no behaviors in the top right-hand corner, go back and generate another Swarm of Bs. If there are any one-off behaviors on the list, prioritize these. They often solve the problem faster.

How Not to Choose Target Behaviors

Here are some common behavior matching methods that don’t work:

- Random guessing. Don’t look out the window at a random cyclist, buy all the gear, slog through one commute to work, and realize it’s not for you. Be as methodical as you can in this process. Set yourself up for success through design—don’t depend on luck.

- Inspiration from the internet. The internet is a context-free minefield of unrealistic inspiration. Steer clear unless a behavior you see really seems to suit you and fit into your life.

- What worked for someone else. If your mother tells you she’s gone cold turkey on coffee by substituting herbal tea, this doesn’t necessarily mean the same approach will work for you.

Tiny Behaviors are tailored. Yours should feel like they’re made just for you.

Exercise: Pilot the Selection Phase

Sketch out Steps 1 - 3 of the Behavior Design Process for a habit that’s meaningful to you.

Step 1. Pinpoint your exact aspiration or outcome.

Generally speaking, what would you like to achieve? Is it an aspiration (an abstract idea) or an outcome (a concrete result)?

Is this aspiration or outcome really targeting the underlying problem? Will implementing good habits in this domain have a direct effect on the problem? If not, come up with a new aspiration that better describes what you want to achieve.

Step 2. Brainstorm possible behavioral solutions.

Now you’ll create a diverse lineup of behaviors (“Swarm of Bs”) that might help you to achieve your aspiration and outcome.

If it’ll help you to focus, you could set a timer for two or three minutes. Include:

- One-off behaviors (deleting a social media app from your phone; buying a set of high-quality kitchen knives for food prep)

- Fresh habits to cultivate

- Unhelpful habits to drop

Step 3. Identify the Golden Behaviors.

In this step, Focus Map to find your ideal behavioral targets for change. Write your Swarm of Bs on index cards, Post-it notes, or small pieces of paper. Sketch the axes below on a large piece of paper. (Shortform note: You could also do this digitally, using a tool such as Google Jamboard that allows you to move around digital Post-its.)

Step 1: Impact. Arrange your behaviors along the vertical axis by looking at each and asking the question: Will this behavior help me to achieve my aspiration or outcome?

Step 2: Feasibility. Consider each behavior individually, asking the question: Can I realistically get myself to do this behavior? Move each behavior to the left or right on the horizontal axis according to the answer.

Which behaviors have ended up in the top right corner? Do they feel inviting and achievable?

Chapter 3: Behavior Design Phase 2—Design

The complete Behavior Design process consists of seven steps. We looked at Steps 1 to 3 in Chapter 2. Now we’ll learn about Steps 4 and 5, which comprise the Design phase of the new habit.

Selection

Pinpoint your exact aspiration or outcome

Brainstorm possible behavioral solutions

Identify the Golden Behaviors

Design

4. Find the tiny version

5. Choose your prompt

Practice

Celebrate

Repeat, refine, and upgrade

4. Find the Tiny Version

How do we make behaviors so easy that they shoot up above the Action Line?

We have two options for making behaviors easier: practicing more and working with the Ability Chain.

Practice

With each repetition a behavior gets easier, pushing it further to the right on the Ability axis. However, repetition isn’t the answer for all behaviors.

The Ability Chain

You can visualize the Ability component in B = MAP as a chain with five links: time, money, physical effort, mental effort, and compatibility with existing routines. As with all chains, the Ability Chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

To target Ability effectively, we use two questions: a discovery question and a breakthrough question. The discovery question diagnoses the weak link. The breakthrough question tells us how to strengthen it.

Diagnosing the Weak Ability Chain Link

The discovery question is: What is making this behavior difficult?

“Difficult” doesn’t have to mean very difficult—it refers to any amount of difficulty that is stopping you from doing the behavior.

Often our perception of the difficulty is more important than the actual difficulty of an activity.

We can break down the discovery question into five parts, one for each chain link:

- Do I have enough time to do this?

- Do I have enough money to do this?

- Does this require a lot of physical effort?

- Does this require a lot of mental effort?

- Can I incorporate this easily into my daily routine?

Let’s say you want to start eating blueberries as a daily snack.

- Time. Eating blueberries doesn’t take a lot of time.

- Money. Fresh blueberries can be quite expensive.

- Physical effort. Eating blueberries doesn’t require much physical effort.

- Mental effort. Eating blueberries doesn’t require mental effort.

- Daily routine. It’s easy to incorporate eating blueberries into most daily routines.

The weak link for this habit seems to be money. Because fresh blueberries are expensive, perhaps you don’t buy enough when you go to the store to be able to eat them every day.

Because money is the weakest link, this should be the target of your solution. Buying blueberries frozen or in bulk might be the trick to establishing this habit in your life.

Strengthening the Weak Ability Chain Link

Once we’ve diagnosed the problem, we need to generate solutions.

The breakthrough question is: How can I make this easier? We can use the PAC acronym for this: Solutions can be Person-based, Action-based, or Context-based.

Person. Change something about yourself to make the activity easier. This means “skilling up”: increasing your skills to make the activity easier in the future. You can skill up through:

- Watching YouTube videos (there’s a video for pretty much everything)

- Reading a book

- Taking a class

- Asking someone to teach or show you how to improve

Skilling up is most natural during a motivation surge. Take advantage of motivation surges to skill up—this investment will make a difference later, when your motivation is low.

Action. Change the action itself to make it easier (more on this in a moment).

Context. Change something about your environment to make the activity easier. You can work with context through:

- Investing in a helpful tool (such as better dental floss, a salad spinner, or good walking shoes)

- Rearranging your environment (store something where you can reach it, reorganize the fridge)

Manipulating the action itself is a key strategy in Tiny Habits. If you shrink the behavior enough, you can do it no matter how low your motivation sinks. There are two ways to approach making behaviors tiny:

1. Starter step. This is the very first “baby step” towards the behavior you want to cultivate. It can create a surprising amount of momentum. For example:

- Desired behavior: Walk for 30 minutes daily. Starter step: Put on your walking shoes.

- Desired behavior: Tidy up after meals. Starter step: Stack the plates.

- Desired behavior: Cook yourself breakfast. Starter step: Turn on the stove burner.

2. Scaling back. This is a pared-down version of the behavior you want. For example:

- Desired behavior: Walk for 30 minutes daily. Scaled-back version: Walk to the front gate.

- Desired behavior: Tidy up after meals. Scaled-back version: Put dishes in the sink.

- Desired behavior: Cook yourself a healthy breakfast. Scaled-back version: Make instant microwave porridge.

In all cases, it’s important to keep the target behavior tiny. Don’t get excited and make the baseline behavior more ambitious—especially not early on. If you cooked yourself a gourmet breakfast yesterday, it’s perfectly fine to just turn on the burner today. The most important thing is to keep the tiny habit alive.

Your New Habit Is Like a Plant

When you start a Tiny Habit, you’re planting a seedling. If you don’t water this seedling a little bit every day, it will die. Daily watering, even with only a few drops of water, keeps the plant alive.

With consistent daily watering, the seedling starts to grow roots, making it more stable. It also starts to naturally grow bigger and taller. After an extended period of daily watering, the plant will be strong enough to withstand storms and will be flowering in all kinds of unexpected ways.

Consistent Tiny Habits can carry you through unexpected life “storms” such as illness and psychological adversity. These habits often ripple out and have unexpected positive effects on other areas of your life.

Consistency Is Key

Completing the behavior consistently is like watering your plant faithfully. It only needs a few drops of water every day, but without that baseline, the plant will wither and die.

Tiny Habits should feel easy, and growing them should feel like fun, not like a chore. It doesn’t matter how elaborate your habit becomes over time—the low baseline is always the same tiny version, and doing more is always optional.

Example: Flossing One Tooth

For years, Fogg had problems developing a daily flossing habit. Immediately after dentist visits he felt very motivated, but this motivation quickly disappeared within a few days. As a behavior scientist specializing in habits, this was quite embarrassing!

He examined the flossing habit using the above five questions, and—surprisingly—found that physical effort was the weak link. Fogg’s teeth are particularly close together, so it’s hard work to get the floss in and out, and the floss often breaks and gets lodged between his teeth. So he targeted the physical effort dimension by testing out 15 different types of floss, finding the best fit for his teeth, and scaling back to a habit of just flossing one tooth.

After two weeks, he was flossing all of his teeth twice daily. He eventually became something of a floss connoisseur, signing up for a personalized tour of a floss factory while on a trip to Dublin. On days of particularly low motivation, he still flosses just one tooth.

After you’ve manipulated the Ability dimension to find a promising Starter Step or Scaled-Back Version, you’re ready to design your prompt.

5. Choose Your Prompt

As with motivation and ability, prompts can be based on P (Person), A (Action), or C (Context).

In Person prompts, you remind yourself to do the action. The most reliable subset of these is using primary physical needs as your reminder. For example, you feel hungry, so you eat.

Here’s an example. Fogg wanted to do pushups throughout his day. He decided to use peeing as the prompt, and now has an established habit of doing at least two pushups immediately after he pees.

But person prompts can be unreliable, especially if they rely on your memory.

In Context prompts, something in your environment reminds you to do the action. Post-its, notes on your hand, phone notifications, reminders from others, and putting something where you can see it are all examples of context prompts.

Context prompts can become overwhelming, and it’s easy to become habituated and start to ignore them. We can manage context prompts in our environment by silencing our phones, hanging up DO NOT DISTURB signs, and directing people to certain communication channels (for example, not using text messaging for work purposes).

Context prompts can be effective, but design is important. If a context prompt isn’t working, design another prompt and try again.

In Action prompts, an existing action in your routine prompts a new action. For example, brushing your teeth prompts you to floss, setting your coffee on the desk prompts you to look at your To Do list, hanging up your coat when you get home prompts you to play with the dog.

This is like computer code: if you get the sequence right, there’s a predictable outcome.

Action prompts are the “secret sauce” of Tiny Habits and are also known as Anchors. We first encountered Anchors in the Introduction, in the ABC Tiny Habit recipe mnemonic: Anchor, Behavior, Celebration.

The key to an effective prompt is after. The desired behavior should be executable immediately after the prompt. A well-designed prompt has a clearly defined ending, and this ending serves as a cue for the desired behavior.

Advice on Implementing Anchors

Morning routines are better because they’re more stable. Later in the day, our routines are more likely to fall apart. Analyze your desired new habit and tailor the Anchor accordingly. Where does the habit fit best into your routine?

There are a few different ways to pair new habits with Anchors. These are, from most to least effective:

Pair by location. Can you find an Anchor that you already do in the same place? (Pair a new habit in the garden with something you already do regularly in the garden.)

Pair by frequency. How often do you want to do the new habit? (Pair a new once-a-week habit with something you already do once a week.)

Pair by objective. Can you find an Anchor that shares a common goal with your new habit? Note that this is very personal. If your morning coffee is a signal to jump into your work day, you could pair it with looking over your To Do list. But if it’s about quiet, reflective time, you could pair it with taking three deep breaths.

Sarika, whom we met earlier, paired watering her houseplant with taking a drink of water herself. This way, when she nourished the plant with water she also nourished herself.

Bad Anchors don’t match any of the above. “After I take a shower, I will sort the laundry” doesn’t match location, frequency, or objective. This new habit has a low chance of success.

Anchors need to be clear. If an Anchor isn’t working, perhaps it’s not clear enough. To solve this, look for the “Trailing Edge”: the exact moment when the action ends.

For example, “after I get home from work” is a fuzzy Anchor. Does getting home from work end when you walk in the door? When you put down your bag? When you change out of your work clothes? Find the Trailing Edge and anchor the new habit to that.

It helps to look for a final action that gives you a sensory cue, for example:

- The sound of the water turning off as a cue to wipe the kitchen bench.

- The sound of a car door closing as a cue to write a task on a Post-it.

If it helps, look for a strong Anchor first and then decide which behavior to pair with it. Are there any regular actions in your daily routine with clear-cut edges? What new habit could you introduce there?

If an Anchor doesn’t work, keep experimenting. Change the recipe to see what works best. By experimenting, you’re improving your skills in pairing habits with Anchors in the context of your own preferences and routine.

You’ll know when something feels right.

Using Prompts in Business

Fogg believes that successful businesses of the future will rely less on context prompts and more on action prompts. For example, a medical insurance company might ask its customers about their daily routines and use this information to tailor its reminders to clients.

Example: Amy and the Car Door

Habiteer Amy owns her own business and she’s struggling to accomplish business-related tasks. Each morning, she drives her daughter Rachel to school. After she says goodbye to Rachel (more specifically, when Rachel closes the car door), Amy drives immediately to a free nearby parking space and does her Tiny Behavior: writing her most pressing task for the day on a Post-it note. She then drives home and puts the Post-it on the wall near her desk. On most days she goes on to do the task, and this generates momentum for completing other pending tasks. On some days, she doesn’t do the task—but as long as she’s written it on the Post-it, the habit is secure.

This prompt of Rachel closing the car door is effective because:

- It’s linked to a sensory cue (sound of car door closing)

- It’s the first task in Amy’s work day

- It fits seamlessly into her existing daily routine.

Special Types of Tiny Habits

There are a few types of habits that are built on special prompts. “Meanwhile Habits” are small habits that you can use to fill otherwise useless or dead time. “Pearl Habits” are habits that take prompts that would otherwise trigger negative emotions or unhelpful behaviors and turn them into prompts for positive emotions and helpful behaviors.

Meanwhile Habits

You can introduce “Meanwhile Habits” while waiting for something else to happen. For example, you could do a Meanwhile Habit when:

- Standing in line

- Waiting for the shower water to heat

- Waiting at a red light

- Vacuuming the house

In Meanwhile Habits, unlike other types of habits, the prompt is the beginning of a particular situation rather than the end. The purpose of Meanwhile Habits is to fill otherwise empty fragments of time, so these habits will stay tiny rather than growing bigger.

Pearl Habits

Like pearls, Pearl Habits start with an irritation and grow into something beautiful. When creating a Pearl Habit, you convert a periodic annoyance in your environment into the prompt for a positive new habit.

Here’s one example of a Pearl Habit. Fogg had an air conditioner in his bedroom with a noisy thermostat that clicked whenever the A/C turned on and off. This woke him up, which was annoying. Instead of installing a new thermostat, he experimented with using the click as an Anchor reminding him to relax the muscles in his face and neck. Now he’s happy when he hears the click, because it’s helping him to sleep rather than waking him up.

Here’s another, more impressive example. Amy (of the closing car door prompt) was going through an acrimonious divorce in which her husband regularly insulted and verbally assaulted her. She turned her husband’s behavior into a prompt to do something nice for herself.

This changed how she reacted to the insults. She began to accept them with more equanimity, and even welcome them: His bad behavior became an opportunity to watch her favorite movie or book a massage.

Over time, her ex-husband saw that his insults weren’t affecting her anymore, and he gradually stopped behaving badly. The kids, who in the past had had to watch the abuse, also benefited. The relationship between Amy and her ex-husband improved so much that after a few years they worked together to throw their daughter’s graduation party.

Exercise: Work With the Ability Chain

Identify strong and weak links in the Ability Chain.

The “Ability Chain” has five links: time, money, physical effort, mental effort, and compatibility with daily routine. Think of a specific habit that you’d like to implement, or that you’ve been trying to implement without success. Assess each link in the chain individually. Which is the strongest? Which is the weakest?

Any chain is only as strong as its weakest link. How could you strengthen the link that you’ve identified as being weakest?

Exercise: Use Starter Steps and Scale Back

Practice creating your own Tiny Habit.

There are two types of Tiny Habits that you can implement: “starter step” and “scaling back.” A stater step is when you isolate the very beginning of the behavior. (For example, if you want to start drinking a big glass of hot water with lemon every morning, a starter step might be putting the kettle on to boil.)

Pick one or more new habits you’d like to introduce and list a few possible starter steps.

A scaled-back version is a smaller version of the whole behavior. A scaled-back version might be making the lemon water and taking one sip.) For the same habit(s) you considered above, list a few possible scaled-back versions.

Exercise: Create a Pearl Habit

How might you turn an annoyance into a cue for positive change? In Pearl Habits, you transform events that usually prompt you to react negatively into prompts for a positive habit. (For example, Fogg turned the noise of an air conditioner into a prompt to relax.)

Think of a few stimuli that usually annoy you or trigger a negative reaction.

Which stimuli have the potential to become a Pearl Habit? What positive behavior could you use them to prompt?

Chapter 4.1: Behavior Design Process Phase 3—Practice (Celebration)

The Behavior Design process consists of seven steps. We’ve covered Steps 1 to 5 in Chapters 2 and 3. Now let’s look at the remaining steps, which comprise Phase 3 of the process: Practice. As there’s a lot of detail here, we’ve split Phase 3 into two chapters. In Chapter 4a we’ll look at Step 6 (Celebration), and in Chapter 4b we’ll look at how to repeat, refine, and upgrade the habit.

Selection

Pinpoint your exact aspiration or outcome

Brainstorm possible behavioral solutions

Identify the Golden Behaviors

Design

Find the tiny version

Choose your prompt

Practice

6. Celebrate

- Repeat, refine, and upgrade

We first encountered Step 6 (Celebration) in the “recipe” in the Introduction:

We first encountered Step 6 (Celebration) in the “recipe” in the Introduction:

- After… [Anchor]

- I will… [Tiny Behavior]

- To celebrate, I will … [Celebration]

We now have a good understanding of the first two ingredients, the Anchor and the Tiny Behavior. But what exactly does a Celebration look like?

Step 6. Celebration

As we saw in the Introduction, we change best when we feel good. But feeling good can be more complicated than you might think. How do we make ourselves feel good about a new habit? In the most challenging cases, how can we cut through the years of negative emotional baggage and “self-trash-talk” that have accumulated around this behavior? The answer is Step 6 in the Behavior Design process: celebration.

Celebration is absolutely fundamental in Tiny Habits. Fogg writes in this chapter that if a reader takes away one thing from the book, it should be the value of celebrating our tiny successes.

Despite this, many Habiteers (even professional coaches) are inclined to skip it. Some don’t take it seriously because it doesn’t seem important. Others feel self-conscious or silly about celebrating.

Because of this, celebrating is the very first skill you should tackle when starting out with Tiny Habits. Once people implement this step, it changes their whole outlook. Many actually start wanting to do their new habits just so they can celebrate afterwards.

Celebration is the core of Fogg Behavior Maxim #2: Help people feel successful. Note that this isn’t “Help people be successful.” Actual success, externally measured, isn’t important. It’s the ability to feel successful that we’re aiming for—which for many of us can be even more challenging than achieving external success.

Celebration is important because through celebration we cultivate the important skill of making ourselves feel good. This is important not only when working with new habits, but also in building emotional resilience in the face of challenging life circumstances.

Above all, celebration is a way to practice being kind to yourself. Many of us could use some extra skills in this area. Celebration helps us defy society’s unrealistic expectations about behavior change and switch to a gentler, more sustainable way of being.

In fact, if you have children or if you spend time caring for someone else’s children, try to cultivate their celebration of small successes wherever you can. Children are naturals at celebration, so this shouldn’t be hard. Building in celebration now will help later on, when social norms start to dampen this natural exuberance. Habiteers consistently say that they wish they’d learned this particular skill earlier, as practicing it has changed their lives in radical ways.

Celebration is only necessary when establishing a habit. After the habit has grown strong roots, you don’t need to keep celebrating—though you certainly can if you want to!

Shine

“Shine” is the feeling you’re aiming to access through celebration. Fogg invented this term after realizing that English didn’t have a good word to capture the feeling he was talking about: “authentic pride” came closest, but wasn’t succinct or accurate enough.

Shine is a feeling of mingled joy and success. You get this feeling when an authority figure you admire praises you, or maybe when you’re relaxing in the sun on a beach or cuddling with your child or pet. We’ll give you a list of suggested celebrations later on. Try out a few of those to see if they invoke a feeling of Shine for you.

Celebration in Tiny Habits: Origin Story

Fogg’s tooth-flossing Tiny Habit was introduced in Chapter 3 as a new habit that was the seed for the Tiny Habits method. It was also the habit that taught Fogg the importance of celebration. The remainder of the flossing story is as follows:

It was a very stressful time in his life. His nephew had just passed away, his business was failing, and everything felt like it was on the verge of falling apart. He thought, “If everything else is collapsing around me, at least I can accomplish one thing—I can floss one tooth.”

He flossed one tooth, then smiled at himself in the mirror and silently said, Victory! Immediately after that, he felt an emotional shift. The emotion made him want to floss again so he could feel good again amidst all the difficulty.

This celebration became a stable positive point in his day when everything else was unstable and difficult. He introduced celebration when cultivating other habits and noticed that it helped him automate the habit faster. He also noticed that he could access the same feeling via different types of celebrations (a thumbs-up, a visualization, an encouraging phrase said to himself silently).

After making these observations, Fogg combed the scientific literature on celebration (which was surprisingly sparse) and observed the public celebrations of athletes, looking for common threads.

Though there aren’t many scientific papers published specifically on celebration, there’s a huge body of work on the brain’s reward system and how it works.

The Mechanics of Celebration

Conscious celebration allows you to harness powerful brain networks to your new habit.

The brain network we’re “hacking” through Tiny Habits is the reward system. This system has evolved over millions of years to keep us alive, healthy, and safe.

Whenever you feel good, your brain notes and reinforces the actions you performed to get there. This means that experiencing pleasure helps you to encode new behaviors. When you experience pleasure (or, more specifically, an outcome that yields a “reward prediction error,” in that the outcome was better than you expected), your brain releases a shot of dopamine. This dopamine helps to lock in the habit.

What Are Rewards?

Like “goal,” the word “reward” is conceptually fuzzy, and its technical meaning is frequently lost in translation between academic research and self-help books. Because of this lack of precision, the word “reward” isn’t used much in Tiny Habits.

For many people, “If I go to the gym now, I’ll watch a movie tonight” is a reward. But in the technical sense (and the sense that matters to us here), this isn’t the case.

It helps to distinguish between “incentives” and “rewards.” The difference is timing. Incentives are ways to encourage a particular behavior. The benefit can appear well into the future. Examples of incentives are:

- “If I keep the kitchen counter tidy all week, I’ll buy that new blender I’ve been eyeing in the store.”

- “If you sell 100 products this month, you’ll get a 20% sales bonus.”

Incentives can certainly motivate you to do something, but they don’t have a direct effect on your brain.

Rewards are tied to the behavior in real time: You take a bite of chocolate and a delicious taste fills your mouth, or you finish a presentation and the audience begins to clap.

Rewards need to occur either while the behavior is happening or very shortly afterwards (ideally within milliseconds). This is because dopamine is metabolized quickly in the brain.

Celebrations, like Tiny Habits, should be tailored for best results.

Characteristics of a Great Celebration