1-Page Summary

In Ways of Seeing, published in 1972, art critic John Berger argues that throughout history, the way we see art has been manipulated by a privileged minority to preserve their social and economic dominance.

This text challenges the idea that to understand and appreciate works of art, we need experts to “translate” them for us. Rather, Berger urges us to pull back the curtain and look at the images before us with our own eyes.

Ways of Seeing is a collection of seven untitled essays, three of which are visual and contain no text. The essays can be read in any order, and while each essay focuses on a different topic, there are connecting themes of perspective (“ways of seeing”) and mystification.

In this guide, we’ve created a chapter for each of the five topics that Berger discusses in his book. Within each chapter, we present Berger’s analysis of how the topic is currently approached by art critics and the public, if and how mystification is present, and how he believes we should shift our thinking (in other words, our “way of seeing”). We examine Berger’s arguments, add historical background on both the artwork Berger analyzes and the landscape in which Berger is writing, and compare Berger’s ideas to those of contemporary art and culture.

What Is an Image?

An object, living being, or landscape that exists before your eyes in real life is a sight. The couch you are about to sit on, the floor beneath your feet, and the flowers you see in the garden outside your window—these are all sights. An image is a sight that has been reproduced or recreated. The sight becomes an image when it is separated from the place and time in which it truly exists (or existed). A painting, a video, even a photograph—these are images.

Berger says that once a sight becomes an image, it’s no longer an exact record of what was. The act of reproducing a sight inherently adds a subjective value to the image. Rather than being a historical record of the sight, it’s now a record of how someone saw the sight…and how you are seeing the image now.

(Shortform note: When an image is continuously reproduced, you might imagine the meaning being skewed each time—similar to the childhood game of Telephone. With each iteration, a nuance is added or a distortion takes place.)

Our Experiences and Beliefs Influence What We See

Berger argues that our beliefs, experiences, and knowledge strongly influence what we see. Imagine three people are looking at the same image of an iceberg. The person who is concerned with climate change will instantly assign a symbolic meaning and see a melting iceberg within a rapidly heating planet. The person who has been to Alaska will see a landscape that is familiar and majestic. The third person, a history buff, will see what caused the sinking of the Titanic. In each case, the belief, experience, or knowledge influences what the person sees.

(Shortform Note: One study found that the amount of context we receive influences how we interpret visual information. Particularly, when there is little to no context, we tend to fill in the blanks ourselves and think more critically. When given context, our brains naturally move toward it (also known as confirmation bias) and we’re less likely to diverge from the information given. This supports Berger’s argument that what we believe influences what we see.)

The Meaning of Mystification

Berger uses the term mystification throughout Ways of Seeing, and though there are contextual clues as to the implications of the word, he speaks as if the reader is already familiar and provides only one line of definition: “Mystification is the process of explaining away what might otherwise be evident.” Because this term is used so heavily in the text, we’ve added a breakdown of mystification, from its literal definition to the economic context in which it’s used:

- Dictionary definition of mystification: “an obscuring especially of capitalist or social dynamics (as by making them equivalent to natural laws) that is seen in Marxist thought as an impediment to critical consciousness.”

In Marxism, mystification refers to the intentional deceiving of the majority working class (proletariat) by the minority upper/middle class (bourgeoisie) to preserve their wealth. Berger takes this framework of mystification and applies it to the way art is critiqued and owned—particularly the idea that throughout history, art historians and the wealthy elite have obscured ideologies hidden within the art. Though he doesn’t use the term in a strictly Marxist sense, there are clear parallels between the two and it can be inferred that Berger’s Marxist beliefs influenced his perception.

The European Tradition of Oil Painting

The primary topic Berger discusses in Ways of Seeing is the European tradition of oil painting, which he says occurred between the years 1500 and 1900. The technique of oil painting (mixing pigment with oils to create a medium) was around long before the Renaissance, but it became an art form during this period because, for the first time, there was a need to develop and perfect the technique. This need was primarily due to the subjects being depicted: food, pedigreed animals, expensive objects, land, and so on. Tempera and fresco paintings couldn’t produce the intense realism that oil painting could, so to depict these subjects in a way that essentially placed them in the room—the desired effect—oil painting was necessary.

Why Oil Paints Are the Best Medium for Realistic Paintings

Tempera is an egg-based paint that produces muted colors and dries very quickly. Fresco painting is the process of using watercolor paints on wet plaster, which also dries quickly. In both of these mediums, the artist doesn’t have the luxury of taking his time. He also has less control over the paint and mistakes are difficult to fix.

Oil paints, on the other hand, have an extremely long drying time—depending on the solvent used to thin the paint, it can take days, weeks, months, or even years in some cases, to fully cure. This allows the artist to work very slowly and deliberately. The texture of oil paints lends them well to blending, which can produce seemingly infinite shades of color. Unlike other mediums, the colors of oil paints are vivid and saturated, which allow them to be layered on top of one another to create depth and texture, as well as fix mistakes.

Norms of the Tradition: Oil Paintings as a Depiction of Wealth

Berger argues that European oil paintings from 1500-1900 were almost entirely focused on displaying wealth. He explains that oil painting rose to prominence beginning with the Renaissance largely because of its ability to accurately depict tangible items. This made it an excellent medium for depicting subjects that represent wealth and power:

- Expensive objects

- Feasts

- Pedigreed animals

- Land ownership

- Portraits

- Mythology

- Genre paintings

- Colonization

- Nudes

The Hierarchy of Genres

While all the listed subjects depicted or symbolized power, for some viewers, the genres they represented weren’t created equal. From the 17th century onward, many academics believed in a strict ranking of artistic genres based on their perceived aesthetic and moral value.

The first hierarchy of genres was established in 1667 by Andre Felibien, a theoretician of French classicism. He ranked the categories in the following order, from most to least valuable:

History paintings: Paintings with mythological, religious, historical, or literary subjects. The paintings must contain an intellectual or moral message.

Genre paintings: Paintings depicting everyday life.

Portraits

Landscapes

Still lifes

Expensive Objects

Consider this painting by Holbein. If you look closely at what is being depicted, it oozes wealth. Berger describes to us the materials being displayed: marble, velvet, fur, and silk, among others. The men display their privilege through items like books, globes, scientific tools, and musical instruments—symbols of the educated class.

These men surrounded themselves with their most expensive and class-validating possessions and hired an artist (Holbein) to paint them. And this was the norm. Why? That is the question that Berger urges us to consider.

THE AMBASSADORS BY HOLBEIN 1487/8-1543

Achieving Texture With Oil Paints

Berger describes how Holbein painted the textures of velvet, marble, fur, silk, wood, and metal all in one painting. How is this achieved? Most artists agree that experimentation is the best way to learn about texture. Start by playing with the following factors:

Brush stroke: Dabbing, swooping with pressure, lightly sliding, and so on, all produce different looks on the canvas.

Viscosity of the paint: For thick texture (impasto), use the paint straight out of the tube with no medium to thin it. For thinner paints, add a solvent, such as turpentine or mineral spirits. Don’t add too much or your paint will become soapy.

Dry mediums: Try adding sand, pumice, or glass beads to your paint to add an unexpected texture. Use a pallet knife or disposable brush when applying this, as it can ruin your good paint brushes.

Food, Pedigreed Animals, and Land Ownership

Just as expensive objects represent wealth, so did great feasts, expensive pedigreed animals, and ownership of land. These were things that the working class didn’t have, and the wealthy elite who commissioned paintings were proud to have them. Berger says that thousands of paintings from the tradition fell into one of these categories.

(Shortform note: Cornell University conducted a study of more than 750 Western food paintings from the years 1500 to 2000, similar to the years Berger discusses. They added that the foods displayed were often exotic, native to non-Western lands. Fruits were also heavily featured, when in reality vegetables were much more readily available. The study authors warn art lovers to not use these images as a historical record of what was actually eaten at the time; rather, liberties were taken in order to appear as elite as possible.)

Mythology

According to Berger, paintings of ancient myths and religious stories were the most respected category of painting. Because the wealthy elite were educated, they were the minority in society who had access to these myths. But instead of inspiring their wealthy owners to live up to the morality depicted in the paintings, Berger says the paintings instead served only to confirm its owners’ high perception of themselves because they were educated enough to know the stories being told.

Shortform Commentary: A Modern-Day Mythological Painting—Leda and the Swan

Painted in 1962 as one of a set of six, Leda and the Swan is a modern-day mythological painting by Cy Twombly. It’s immediately apparent that this painting is done in a different style than the mythological oil paintings of the European tradition, yet it meets the criteria of the genre. The painting is based upon the Greek story of Zeus seducing Leda by taking the form of a swan. This particular painting sold for over $50 million in 2017, demonstrating that the market value for this genre still tops the hierarchy list previously discussed. Another member of this set currently resides at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Genre Paintings

“Genre” paintings were the opposite of mythological images. Rather than depicting morality and virtue, the genre paintings depicted unrefined vulgarity. The subjects of these paintings were the working class—nameless individuals going about their lives. The genre paintings that follow the tradition depict the working class as poor, but happy. Often, the subject is even smiling outward at the viewer of the painting, presumed to be a member of the bourgeoisie. Berger says this depiction isn’t realistic, but that it kept the wealthy from feeling guilt about their privilege (mystification).

(Shortform note: Many of the masters of the “genre” genre came from the Netherlands, including Vermeer and Steen. The most common scenes depicted included social events, daily pleasure, soldier life, and scenes of drunkenness.)

Colonialism

Just as myth paintings assured elites that they too were moral and therefore deserving of their wealth, paintings that depicted colonized people and places reminded elites that (in their view) their culture was superior and therefore justified violent conquest. Berger explains that the painting in itself (a commodity) and the subject it depicted both contributed to this view.

(Shortform note: Postcolonial theory is a body of thought that claims we cannot understand the world we live in without considering how imperialism and colonial rule has shaped it. “Post” is added to the word colonial because it primarily focuses on colonialism from the 18th to 20th centuries, but the theory doesn’t imply that colonialism has ended.)

The Mystification of European Oil Paintings

Because of the subjects depicted in paintings from this time period, as well as the monetary value the paintings hold as commodities, European oil paintings are ripe for mystification. One of the most prominent ways that art is being mystified today is in how it’s represented and explained through art theory and history. According to Berger, the artists and works that are most represented by museum docents and historians don’t accurately reflect the norms of the European oil painting tradition. As a result, the history of the time is invisible to the viewing public, which means they’re unable to learn from it.

The rise of the oil painting coincided with the rise of the free art market in Europe. Almost all paintings during this time were done on commission, in large part because of the expense of the venture. The wealthier a person was, the more paintings he could commission. Because the paintings were commissioned, the patron had control over what the painting depicted. Berger explains that this is a form of mystification, because if you study the paintings from this time period, you are not seeing a record of what was—you are seeing how the wealthiest class of people wanted to be portrayed. These depictions protected their social status, which is inherently connected to wealth, for all of history.

(Shortform note: Berger explains how mystification benefits the wealthy, but he doesn’t provide a clear argument for how demystification of centuries-old paintings would affect modern-day capitalism. We might infer that if the masses were to understand the class stratification and oppression of the past, they might be more likely to recognize it in modern society and challenge its authority.)

Nudity and Objectivity

Nude women were a prominent subject in European oil painting. Berger points out that in the same way oil paintings depicted wealth using images of land and objects, women were also seen as property to be flaunted. Nudes, Berger says, are characterized by the objectification of the female “subject,” who through the assumed gaze of the male viewer is made into an object.

Nude women in European oil paintings appear for the benefit and use of the assumed male viewer, who Berger calls the “spectator-owner.” He calls them this because the man who owns the painting “owns” the nude woman, and (in his mind) he’s also the reason why the nude woman is there—to display herself for him, the spectator.

(Shortform note: According to Berger, the nudes of the oil painting tradition were highly focused on the spectator-owner and featured the male gaze within the paintings as well. Today’s nudes are less focused on being desirable, and more focused on breaking taboos. In many examples, the woman touches her own body and exudes a sexuality that up until recently was viewed as a character flaw. Since the “Me Too” movement of 2017, women have moved toward unapologetically embracing their sexuality and rebelling against the historical objectivity of their bodies.)

Naked Versus Nude

Not all naked paintings are nudes. According to Berger, to be naked is to be yourself, and to be seen by others for who you are—it is vulnerability and honesty. To be nude, on the other hand, is to hide oneself and be seen by others as an object—usually for sexual fantasy. We can’t know for sure what the subject in an image is feeling, but Berger says there are three primary distinctions between nudes and nakedness that you can visually see in an image:

- The nude is conventionally attractive—the woman’s body is depicted in a way that satisfies man’s desire in a given time period. Nakedness will display “flaws” by conventional standards.

- The nude is present for the purpose of being viewed—she is visibly aware that she is the object of a man’s attention, evident by her eyeline and/or body positioning. Nakedness contains no exhibitionism or voyeurism. The woman is simply living her life as anyone would, which occasionally requires being naked.

- The nude is passive and still—often portrayed lying down in the supine position, the nude is inanimate, just as an object would be. Her face is placid or coy. Nakedness is portrayed using motion and expression—a towel slipping, a woman moving lustfully or appearing surprised, are examples that show that she’s a living human.

When speaking in terms of percentage, Berger explains that nudes are common in European oil paintings, and nakedness is rare. He infers that the rarity exists because the image of a naked woman that doesn’t “belong” to the spectator-owner is not marketable.

(Shortform note: Sir Kenneth Clarke, Berger’s primary adversary, argues that to be naked is to be without clothes and to feel exposed or embarrassed because of it. It’s a vulnerable state of being. To be nude, he says, is intentional and comfortable. A nude represents a particular society’s ideal figure. This means that a nude in one country or one time period will be different than that of another.)

The Impact of Reproduction

The invention of the camera (and therefore a means to reproduce images) forever changed how art was viewed, understood, and appreciated. For the first time in history, art could travel to the viewer, and the viewer could be anywhere in the world. As one form of mystification lifted, room was made for a different sort—the intentional distortion of meaning through physical manipulation of the image.

Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Era of Mechanical Reproduction”

Berger notes that his discussion in this section draws heavily on philosopher Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Work of Art in the Era of Mechanical Reproduction.” Benjamin argued that reproduction of art devalues what he calls its “aura,” or its special, noble, meaning-giving power, which is present in the original work. Without connection to its physical place or the special moment-in-time quality of art that makes it timeless, art is open to political co-option.

Reproduction Removes the Art From Its Intended Home

The original meaning of a painting is distorted each time it’s viewed in a new location. Imagine that you’re viewing a painting of Jesus Christ on a crucifix. You’re standing in front of the original painting in a beautiful cathedral, surrounded by hushed whispers, ornate stained glass, and soaring ceilings. Now imagine you are looking at a replica of that same painting, and it’s hanging on the wall of your grandmother’s living room. It’s reasonable to assume that your reaction (and your interpretation of the work) would differ between the two experiences.

(Shortform note: While smartphones are undoubtedly a way art and music are divorced from place, some artists are using smartphones to create intentional place-based work. Using GPS, a Washington D.C. band created an album that you can only hear if you’re at the National Mall, listening on your phone. If you walk too far away from the Mall, the album won’t play.)

Reproduction Breaks the Whole Into Parts

Before reproduction, paintings were only ever viewed and analyzed in their entirety. After reproduction, paintings could be interpreted based on individual sections. Why would someone display part of a painting rather than the whole thing? Berger explains the motivation: When a person has the freedom to pick and choose which sections of a painting to display, they gain control over the message that it sends. (Shortform note: Modern technology has made cropping photos easy and instant. Nearly every smartphone has a photo editing feature where you can separate an image into parts in the blink of an eye. It’s considered unethical for journalists to crop a photo if it’s going to change the meaning of the photo, but some news outlets engage in this behavior anyway.)

Proximity to Words

The content of the words placed beneath or beside an image isn’t as important as the way it changes how we interpret the image. Berger notes that when a piece of art stands alone, the viewer takes it in (along with the setting, as we discussed earlier in this chapter) and draws meaning. When words are present, however, that creative process is halted. Instead, the image becomes an illustration of the words.

(Shortform note: A modern-day example of words changing the meaning of an image can be found in memes. A meme is a digital image that is copied over and over with slight variations and passed along, usually for the sake of humor.)

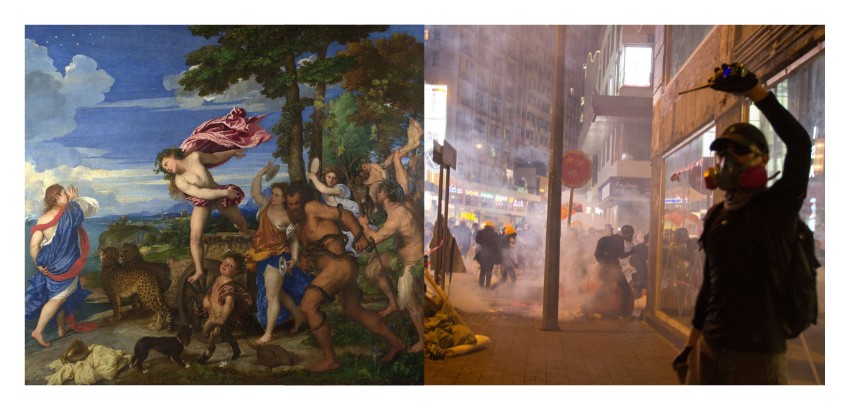

Proximity to Another Image

Just as words can alter the meaning of an image, two images placed side by side can have the same effect. Berger argues that what is seen immediately after an image, when there is no chance for digestion, changes its meaning. (Shortform note: This is another strategy often used by the media to convey a particular message. For example, a newspaper might print a photo of a protest directly next to a photo of a politician. This doesn’t mean the protest is about him, but that’s the meaning derived by their proximity.)

Advertisements in the Modern Age

We can see a throughline from traditional oil painting to modern advertisements.

Every advertisement you see offers a different product or service, but Berger explains that they all promise the same thing: An improved life. By spending money on this or that, your life will become more fun, more relaxing, more convenient. You will improve as a person. Others will envy you and emulate you. (Shortform note: The examples that Berger uses almost entirely focus on the promise of being envied. Today, advertisements tend to focus more on offering convenience. We can infer that the demands of the time dictate what is being promised to the consumer.)

Advertisements and Reproduction

Most advertisements don’t explicitly display fine art, but when they do, Berger points out that they use all of the techniques discussed in the chapter on reproduction: Separation of art from its original home, breaking of the whole into parts, as well as proximity to words and other images.

Advertisements and Oil Paintings

Berger draws a direct lineage from the oil painting tradition to advertisements of the modern age, with one clear distinction: who the viewer is. Instead of reflecting wealth and desire back to the wealthy and desired, as oil paintings did, ads use the qualities of oil paintings (desirable objects that can be bought and sold, the self-satisfied expressions of owners and elites of the past) to reflect an ideal of wealth, desirability, and status to the average person. Instead of enforcing a clear, rigid class system, as oil paintings did under aristocracies, ads enforce the less rigid but still clear class system of the present, where it’s technically possible, but unlikely, to rise to the top in wealth and status.

(Shortform note: Advertisers have been shown to cater their methods and choices of products based on the customer’s socio-economic status, so they do have an incentive to keep their customers within the classes they’ve already identified.)

Mystification of Advertisements

Berger argues that the public (especially members of lower economic status) is subjected to constant mystification through advertisements. The true state of the world is hidden or obscured by advertisements every single day, and though they promise a better life, their goal is to maintain the status quo. As soon as you buy whatever is being advertised to you, there is something new being offered—the goalpost constantly moves just out of reach. (Shortform note: Facebook has recently come under intense scrutiny for their advertising practices, with many claiming that their algorithms are discriminatory and oppressive. Lawsuits against Facebook have been launched by the ACLU, the U.S. Department of Housing and Development, the Fair Housing Act, and more.)

Shortform Introduction

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger argues that throughout history, the way we see art has been manipulated by a privileged minority to preserve their social and economic dominance.

This text challenges the idea that to understand and appreciate works of art, we need experts to “translate” them for us. Rather, Berger urges us to pull back the curtain and look at the images before us with our own eyes. Using Marxist-feminist theory, Berger demonstrates how the elite mystifies art analysis, and by doing so, preserves the very capitalism that he is criticizing.

About the Author

John Berger (b. 1926, d. 2017) was a modern renaissance man: He was a painter, teacher, poet, Booker Prize winning novelist, essayist, screenwriter, playwright, journalist, and—most famously—art critic. He is best known for his BBC television series “Ways of Seeing” and its companion book: Ways of Seeing. Berger was born, raised, and educated in London, England, but spent the second half of his life in France, where he died at the age of 90.

Though never an official member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, Berger kept close ties with the association and was a leading figure in the British New Left—a political movement with strong ties to Marxist thought and which advocated for a range of progressive changes to society. Berger’s social and political views greatly influenced his work.

Publicly Available Works by John Berger:

- Read Ways of Seeing (1972)

- Watch “Ways of Seeing,” the original television series on BBC (1972).

The Book’s Publication and Context

Publisher: Penguin Books (1972)

Historical Context

“Ways of Seeing”—the BBC documentary series on which this book is based—was broadcast in January of 1972, and Ways of Seeing was published later that year. At this time in history, the Western world was in the throes of social, political, and cultural transformation. Beginning in the 1960s, enough time had passed following World War II that society shifted from an emphasis on rebuilding to a focus on social issues. Marginalized groups (particularly women and racial minorities) were fighting for equal rights, and hippie culture prioritized self-realization over materialism. Berger’s ideas were presented at a time when society was ready and willing to embrace a shift in perspective—especially to one that criticized the establishment.

Intellectual Context

“Ways of Seeing” has been heralded as a revolutionary response to Kenneth Clark’s 1969 BBC art program, “Civilisation,” which traces European art history from the Middle Ages to the early 20th century. In his program, Clark argues that art holds an inherent meaning that only an experienced art historian can uncover; in other words, there is a correct way to interpret art if you are educated and experienced enough.

Berger held a decidedly different perspective: that the meaning of art is relative to who views it, along with its place and time in history. Berger was also deeply concerned with class stratification and the contributions and circumstances of people traditionally left out of art history, whereas Clark (who hailed from a wealthy family) wasn’t.

While Clark set an example for a means of public conversation about art, Berger’s arguments have been more foundational to modern discourse. In 2018, the BBC series “Civilisations,” by Simon Schama, Mary Beard, and David Olusoga took up the project of updating and expanding the concept of “Civilisation” to cover world art history, not just European art history. Though it’s a direct line to Clark’s original, many commentators say the series owes a greater debt to John Berger and “Ways of Seeing” for its emphasis on individual and cultural relativity.

The Book’s Impact

Berger’s ideas in Ways of Seeing inspired fierce debate on both sides of the Atlantic and spurred what has been described as a revolution in the way we think about art and art history. Today, Ways of Seeing is a foundational text in many college art courses and has sold over a million copies.

The Book’s Strengths and Weaknesses

Critical Reception

Following Berger’s death in 2017, critics took a renewed interest in Ways of Seeing. Contemporary reviews of the 50+ year-old book are overwhelmingly positive, with many noting how relevant Berger’s views still are today—particularly regarding the exploitation and voyeurism of the female form.

Of the critiques of the series (and, therefore, the book), one pattern emerged: Critics take issue with the way Berger describes the European tradition of oil painting—most commonly, they disagree with his stance that the “masters” broke with conventional methods and, as a result, shouldn’t be used to analyze the time period’s painting traditions.

Commentary on the Book’s Approach

Ways of Seeing is a collection of seven untitled essays, three of which are visual and contain no text. Berger informs the reader that these essays can be read in any order, and while each essay focuses on a different topic, there are connecting themes of perspective (“ways of seeing”), and mystification.

In the book’s introduction, Berger emphasizes that his text isn’t a prescription for one way to think about and interpret art; rather, it’s an invitation to think critically about the way art is presented to us and how we’re told to interpret it.

Our Approach in This Guide

In this guide, we’ve created a chapter for each of the five topics that Berger discusses in his book. In addition, we’ve added a section in the first chapter that presents background information on Marxist feminism and mystification—two themes that Berger weaves throughout the five topics.

The five topics include:

- How we see art—literally and figuratively

- The European tradition of oil painting

- Nude paintings and the objectivity of women

- The invention of the camera and the impact of reproduction

- Advertisements of the 20th century

Within each chapter, we present Berger’s analysis of how the topic is currently approached by art critics and the public, if and how mystification is present, and how he believes we should shift our thinking (in other words, our “way of seeing”). We examine Berger’s arguments, add historical background, and compare Berger’s ideas to those of contemporary art and culture.

Chapter 1: How We See

Berger begins with an in-depth look at how we see, arguing that before we can analyze how we see art, we must first understand how we see images in general. The concepts in this section are the vocabulary and foundation for Berger’s overall thesis, so in addition to the basics of how we see, we’ve added an explanation of Marxist feminism and mystification.

What Is an Image?

Foundational to art analysis is the concept of what an image is. Berger makes a clear distinction between a sight and an image.

An object, living being, or landscape that exists before your eyes in real life is a sight. The couch you are about to sit on, the floor beneath your feet, and the flowers you see in the garden outside your window—these are all sights.

An image is a sight that has been reproduced or recreated. The sight becomes an image when it is separated from the place and time in which it truly exists (or existed). A painting, a video, even a photograph—these are images.

Berger says that once a sight becomes an image, it’s no longer an exact record of what was. The act of reproducing a sight inherently adds a subjective value to the image. Rather than being a historical record of the sight, it’s now a record of how someone saw the sight…and how you are seeing the image now.

(Shortform note: When an image is continuously reproduced, you might imagine the meaning being skewed each time—similar to the childhood game of Telephone. With each iteration, a nuance is added or a distortion takes place.)

Seeing Is Subjective

Images are inherently subjective—a human reproduced the sight (creating an image), another human is viewing the image, and no human can be completely objective. Berger explains that even with a photograph, which is generally considered a more accurate reproduction than a painting, the photographer makes dozens of conscious and subconscious decisions that affect the message conveyed—lighting, positioning, filters, focus, and so on. The viewer then looks at the photograph and interprets what he sees based on a lifetime of experiences that inform his perspective.

(Shortform note: The fact that seeing is subjective is beneficial to the industry of art itself. The phrase “It’s an art, not a science” is a direct reflection of the subjective nature of art.)

Our Experiences and Beliefs Influence What We See

Berger argues that our beliefs, experiences, and knowledge strongly influence what we see.

Imagine three people are looking at the same image of an iceberg. The person who is concerned with climate change will instantly assign a symbolic meaning and see a melting iceberg within a rapidly heating planet. The person who has been to Alaska will see a landscape that is familiar and majestic. The third person, a history buff, will see what caused the sinking of the Titanic. In each case, the belief, experience, or knowledge influences what the person sees.

(Shortform note: One study found that the amount of context we receive influences how we interpret visual information. Particularly, when there is little to no context, we tend to fill in the blanks ourselves and think more critically. When given context, our brains naturally move toward it (also known as confirmation bias) and we’re less likely to diverge from the information given. This supports Berger’s argument that what we believe influences what we see.)

To See Is to Place Yourself Within the Image

Berger argues that when you see an image, you place yourself within it. If you look at an advertisement for a Hawaiian resort, for example, you’ll imagine what it would feel like to be there. You generate ideas about how it would feel, smell, look, and so on, based on your beliefs, experiences, and knowledge. This act of inserting yourself into the image can happen in the blink of an eye and without your consent. It’s the reason we wince when we see a movie character break a bone—we don’t always want to place ourselves in the image, but we do it anyway.

Berger warns that if we’re manipulated into believing an image has a certain meaning, we place ourselves into that meaning. And if the meaning is obscured (mystified) altogether, then we’re deprived of the history that may benefit us in our present. He argues that the elite have been doing this to the working class since the Renaissance, and in later chapters, we’ll take a look at the examples he uses to illustrate this argument.

(Shortform note: Placing yourself within the image doesn’t necessarily mean that you agree with the message that’s being communicated. A famous quote from F. Scott Fitzgerald tells us that “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time…” Perhaps Berger doesn’t give the public enough credit to believe they can experience the image without becoming swept away by its belief system.)

Marxist Feminism and Mystification

Berger’s arguments are complex, and though he references them, he doesn’t provide concrete background information about Marxism or feminism, or a clear definition of mystification. For those reasons, it’s helpful to have an overview of these themes before diving in.

Marxist Feminism

Marxist-feminist theory is based upon the belief that gender inequality and capitalism are inextricably linked, and that women are the greatest sufferers of capitalistic societies. In The Communist Manifesto (originally published in 1848), Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels detail how the Bourgeoisie treated women as both property and a means for production.

The book was written at the tail-end of the Industrial Revolution, which gave rise to capitalistic society. The roles of women drastically changed during this time period—women and children commonly worked alongside men in factories (at one-third to one-half the salary of men), and women were expected to perform unpaid labor at home as well. The machines of capitalism could keep running as long as women remained financially dependent upon their working husbands and continued to produce more workers (children) via procreation.

Fast forward 124 years to 1972, when Berger wrote Ways of Seeing. Feminism took center stage during the 1960s and 1970s, and the public had a renewed interest in Marxist and socialist theories. Berger was an active member of the British New Left and kept close ties with the Communist Party of Great Britain, both of which were heavily involved in the feminist movement. Although a great deal of this book analyzes works produced hundreds of years before The Communist Manifesto was written, Berger uses his political point of view and art history knowledge to draw direct comparisons between the class stratification of that time period and the capitalism of modern advertisements: Specifically, how they both objectify and oppress women.

The Meaning of Mystification

Berger uses the term mystification throughout Ways of Seeing, and though there are contextual clues as to the implications of the word, he speaks as if the reader is already familiar and provides only one line of definition: “Mystification is the process of explaining away what might otherwise be evident” (found on page 15-16).

Because this term is used so heavily in the text, we’ve added a breakdown of mystification, from its literal definition to the economic context in which it’s used:

Dictionary definition of mystify: “to perplex the mind; to make obscure”

Dictionary definition of mystification: “an obscuring especially of capitalist or social dynamics (as by making them equivalent to natural laws) that is seen in Marxist thought as an impediment to critical consciousness.”

In Marxism, mystification refers to the intentional deceiving of the majority working class (proletariat) by the minority upper/middle class (bourgeoisie) to preserve their wealth. In a commodity society such as capitalism, products are made by workers but owned by the workers’ boss, who can sell them for however much he wants. All of the profit from the sale goes to the boss (owner) while the worker receives a set wage. The worker, the labor that goes into the creation of these commodities, and the disparity between his wage and the profit that he generates for his boss, are all invisible—hidden, mystified—to the consumer. This mystification ensures that the rich will get richer and the poor will remain poor.

Berger takes this framework of mystification and applies it to the way art is critiqued and owned—particularly the idea that throughout history, art historians and the wealthy elite have obscured ideologies hidden within the art. Though he doesn’t use the term in a strictly Marxist sense, there are clear parallels between the two and it can be inferred that Berger’s Marxist beliefs influenced his perception.

Exercise: Analyze an Image Using Your Beliefs, Knowledge, and Experience

Berger tells us that what we believe, know, and have experienced influences our interpretation of images. Analyze your own reaction to an image using these insights.

Take a look at the painting below. In 1-2 sentences, what does the image make you think or feel?

What is one belief you hold that may have influenced your reaction?

What is something you know that influenced your reaction?

Finally, what is an experience you’ve had that influenced your reaction?

Chapter 2: The European Tradition of Oil Painting

Every topic discussed in Ways of Seeing connects back to the European tradition of oil painting. Berger argues that understanding the dominant form of art from this period in Europe is key to understanding Western history and social order. Because so many paintings from this era are heralded as markers of artistic and cultural achievement in Western culture, he says it's crucial to understand the politics involved, and why they’ve been erased from (or mystified in) art history.

“The Tradition”

The primary topic Berger discusses in Ways of Seeing is the European tradition of oil painting, which he says occurred between the years 1500 and 1900. This is not a defined period of art history because there were several movements that occurred within it (Romanticism and Realism to name two), yet Berger recognized that this is a distinct period with overlapping norms, hence his classification of the medium and time period as a “tradition.”

While oil painting took off at the beginning of the Renaissance (around the year 1400), Berger argues that the artistic norms of this time period were not fully established until the beginning of the 16th century. The norms continued until Impressionism and Cubism took over at the turn of the 20th century.

The technique of oil painting (mixing pigment with oils to create a medium) was around long before the Renaissance, but it became an art form during this period because, for the first time, there was a need to develop and perfect the technique. This need was primarily due to the subjects being depicted: food, pedigreed animals, expensive objects, land, and so on. Tempera and fresco paintings couldn’t produce the intense realism that oil painting could, so to depict these subjects in a way that essentially placed them in the room—the desired effect—oil painting was necessary.

Why Oil Paints Are the Best Medium for Realistic Paintings

Berger states that tempera and fresco paintings weren’t realistic enough to satisfy the artistic desires of this time period. What made oil paints a superior medium for this purpose?

Tempera is an egg-based paint that produces muted colors and dries very quickly. Fresco painting is the process of using watercolor paints on wet plaster, which also dries quickly. In both of these mediums, the artist doesn’t have the luxury of taking his time. He also has less control over the paint and mistakes are difficult to fix.

Oil paints, on the other hand, have an extremely long drying time—depending on the solvent used to thin the paint, it can take days, weeks, months, or even years in some cases, to fully cure. This allows the artist to work very slowly and deliberately.

The texture of oil paints lends them well to blending, which can produce seemingly infinite shades of color. Unlike other mediums, the colors of oil paints are vivid and saturated, which allow them to be layered on top of one another to create depth and texture, as well as fix mistakes.

Norms of the Tradition: Oil Paintings as a Depiction of Wealth

Berger argues that European oil paintings from 1500-1900 were almost entirely focused on displaying wealth. He explains that oil painting rose to prominence beginning with the Renaissance largely because of its ability to accurately depict tangible items. This made it an excellent medium for depicting subjects that represent wealth and power:

- Expensive objects

- Feasts

- Pedigreed animals

- Land ownership

- Portraits

- Mythology

- Genre paintings

- Colonization

- Nudes

The Hierarchy of Genres

There are ranking systems that exist for genres of the European oil painting tradition, which sorts categories of art forms in terms of value. The first hierarchy of genres was established in 1667 by Andre Felibien, a theoretician of French classicism. He ranked the categories in the following order, from most to least valuable:

History paintings: Paintings with mythological, religious, historical, or literary subjects. The paintings must contain an intellectual or moral message.

Genre paintings: Paintings depicting everyday life.

Portraits

Landscapes

Still lifes

Expensive Objects

Consider this painting by Holbein. If you look closely at what is being depicted, it oozes wealth. Berger describes to us the materials being displayed: marble, velvet, fur, and silk, among others. The men display their privilege through items like books, globes, scientific tools, and musical instruments—symbols of the educated class.

Berger explains that traditionally, art critics explain paintings such as this in terms of technical mastery. The brushstrokes required to accurately depict velvet are quite different from that of marble, or of a human face for that matter. While technical analysis has its value, Berger acknowledges, what is too often missing (mystified) from analyses is what is plainly before our eyes: These men surrounded themselves with their most expensive and class-validating possessions and hired an artist (Holbein) to paint them. And this was the norm. Why? That is the question that Berger urges us to consider.

THE AMBASSADORS BY HOLBEIN 1487/8-1543

Achieving Texture With Oil Paints

Berger describes how Holbein painted the textures of velvet, marble, fur, silk, wood, and metal all in one painting. How is this achieved? Most artists agree that experimentation is the best way to learn about texture. Start by playing with the following factors:

Brush type: Stiffer bristles are more appropriate for applying thick paint, while thinner more delicate brushes can be used for thin applications.

Pallet knives: Instead of using a brush, you can apply paint with a pallet knife to achieve a “frosted cake” look.

Brush stroke: Dabbing, swooping with pressure, lightly sliding, and so on, all produce different looks on the canvas.

Viscosity of the paint: For thick texture (impasto), use the paint straight out of the tube with no medium to thin it. For thinner paints, add a solvent, such as turpentine or mineral spirits. Don’t add too much or your paint will become soapy.

Dry mediums: Try adding sand, pumice, or glass beads to your paint to add an unexpected texture. Use a pallet knife or disposable brush when applying this, as it can ruin your good paint brushes.

Food, Pedigreed Animals, and Land Ownership

Just as expensive objects represent wealth, so did great feasts, expensive pedigreed animals, and ownership of land. These were things that the working class didn’t have, and the wealthy elite who commissioned paintings were proud to have them. Berger says that thousands of paintings from the tradition fell into one of these categories. Here is an example of each:

STILL LIFE WITH A LOBSTER BY DE HEEM 1643

(Shortform note: Cornell University conducted a study of more than 750 Western food paintings from the years 1500 to 2000, similar to the years Berger discusses. They agree with Berger’s assessment that paintings of feasts were intended to cause envy and display social status. They added that the foods displayed were often exotic, native to non-Western lands. Fruits were also heavily featured, when in reality vegetables were much more readily available. The study authors warn art lovers to not use these images as a historical record of what was actually eaten at the time; rather, liberties were taken in order to appear as elite as possible.)

LINCOLNSHIRE OX BY STUBBS 1724-1806

(Shortform note: Many modern art historians say that animals appear in Renaissance paintings as metaphors. Ermines, dogs, birds, and rabbits are listed as recurring animals in religious and secular paintings. Livestock, particularly pedigreed livestock, is not listed among them—which begs the question, is it possible that the ox in this painting is symbolic? Or is it simply an expensive animal standing next to a wealthy man as a display of ownership?)

HENEAGE LLOYD AND HIS SISTER, LUCY BY GAINSBOROUGH 1727-1788

(Shortform note: Gainsborough is heralded as being a master of the portrait and the landscape, but we can infer that Berger would disagree with this assertion. Berger argues that landscapes are natural features that are not owned. If you look closely at Gainsborough’s landscapes, nearly every one shows the landowner standing proudly within it. The J. Paul Getty museum website also describes landscapes as being the “natural world,” but provides examples that include human structures upon them. We can gather that the nuanced definition of a landscape is still up for debate.)

Mythology and “Genre”

Mythology

According to Berger, paintings of ancient myths and religious stories were the most respected category of painting. Because the wealthy elite were educated, they were the minority in society who had access to these myths. But instead of inspiring their wealthy owners to live up to the morality depicted in the paintings, Berger says the paintings instead served only to confirm its owners’ high perception of themselves because they were educated enough to know the stories being told.

Although oil paints are excellent for depicting tangible objects, Berger says intangible concepts like morality and spirituality were difficult to achieve through the medium. As a result, these paintings had a flatness to them, and were more self-serving than examples of artistic mastery.

TRIUMPH OF KNOWLEDGE BY SPRANGER 1546-1627

Shortform Commentary: A Modern-Day Mythological Painting—Leda and the Swan

Painted in 1962 as one of a set of six, Leda and the Swan is a modern-day mythological painting by Cy Twombly. It’s immediately apparent that this painting is done in a different style than the mythological oil paintings of the European tradition, yet it meets the criteria of the genre.

The painting is based upon the Greek story of Zeus seducing Leda by taking the form of a swan. This particular painting sold for over $50 million in 2017, demonstrating that the market value for this genre still tops the hierarchy list previously discussed. Another member of this set currently resides at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Genre Paintings

“Genre” paintings were the opposite of mythological images. Rather than depicting morality and virtue, the genre paintings depicted unrefined vulgarity. The subjects of these paintings were the working class—nameless individuals going about their lives. This is quite different from the commissioned paintings that immortalized the patron’s name in the title of the work.

The genre paintings that follow the tradition depict the working class as poor, but happy. Often, the subject is even smiling outward at the viewer of the painting, presumed to be a member of the bourgeoisie. Berger says this depiction isn’t realistic, but that it kept the wealthy from feeling guilt about their privilege (mystification).

Another mystification in the genre paintings is the hidden message that the poor are less deserving of nice things. This is accomplished by depicting the subjects as sloppy and haphazard. Often their objects are strewn about without care. It implies that a person’s economic status is the result of their virtues, or lack thereof.

Berger points out that the paintings that broke with tradition and showed the darker, grittier side of poverty rarely sold—the people who were able to afford these paintings didn’t want to see this reality.

THE MERRY FAMILY BY STEEN 1668

Genre Paintings’ Moment in the Spotlight

The “hierarchy of the genres” placed the genre artform beneath history paintings, and Berger himself spends far less time discussing this category as compared to that of the history paintings. However, in 16th century Northern Europe (especially in the Netherlands), genre paintings were among the most popular. The rise of Protestantism brought with it a desire for humble works of art—a deviation from the ornate and awe-inspiring frescos of the Catholic church. In fact, the Protestant church rejected frescoes altogether (historians believe this is at least partially due to the climate in Northern Europe: It was too humid for frescoes to dry properly).

Many of the masters of the “genre” genre came from the Netherlands, including Vermeer and Steen. The most common scenes depicted included social events, daily pleasure, soldier life, and scenes of drunkenness.

Colonialism

Just as myth paintings assured elites that they too were moral and therefore deserving of their wealth, paintings that depicted colonized people and places reminded elites that (in their view) their culture was superior and therefore justified violent conquest. Berger explains that the painting in itself (a commodity) and the subject it depicted both contributed to this view.

THE EAST OFFERING ITS RICHES TO BRITANNIA BY SPIRIDIONE 1737-1781

Ways of Seeing and Postcolonial Theory

Postcolonial theory is a body of thought that claims we cannot understand the world we live in without considering how imperialism and colonial rule has shaped it. “Post” is added to the word colonial because it primarily focuses on colonialism from the 18th to 20th centuries, but the theory doesn’t imply that colonialism has ended.

Postcolonial theory emerged in the 1980s as part of a larger conversation that includes feminism and critical race theory. The theory is not so much a set of beliefs as much as it is a lens from which to view history.

Note: An important additional category that existed within the tradition was that of the female nude. It was such a prominent category, and it’s discussed so heavily by Berger, that the next chapter of our guide is dedicated to it.

The Mystification of European Oil Paintings

Because of the subjects depicted in paintings from this time period, as well as the monetary value the paintings hold as commodities, European oil paintings are ripe for mystification.

One of the most prominent ways that art is being mystified today is in how it’s represented and explained through art theory and history. According to Berger, the artists and works that are most represented by museum docents and historians don’t accurately reflect the norms of the European oil painting tradition. As a result, the history of the time is invisible to the viewing public, and is unable to be learned from.

Berger says that hundreds of thousands of paintings fulfilled the norms of the tradition (the ones discussed here as well as in the next chapter), and only a few hundred broke with it. It’s those few that are hailed as the greatest examples of the genre, but Berger argues that they aren’t examples of the tradition at all; rather, they are (and should be recognized as) exceptions to the rule. This isn’t to say that Berger doesn’t respect these artists; quite the opposite, in fact. Because they broke the rules of the tradition, they pushed art forward, which he says is worthy of reverence in itself.

Some of the artists Berger references in this regard are Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Turner, among others. As you can see below, these artists’ most prominent works don’t fall under the established categories (norms) of the tradition.

From left to right:

- The Night Watch by Rembrandt, 1642

- The Milkmaid by Vermeer, 1657/8

- Fishermen at Sea by Turner, 1796

Each of the artists represented above are known for their excellence in a particular theme:

Rembrandt painted in several genres but is best known for his prolific work in portraiture. His portraits broke with tradition by portraying true human emotion and character rather than a static body placed near evidence of wealth.

Vermeer is known for his masterful work of the “genre” genre. He broke with tradition by showing the working class without implications of moral depravity.

Turner was a versatile artist who is best known for his landscape paintings. He broke with tradition simply by depicting landscapes in their natural, non-owned state.

How Wealth and Capitalism Are Protected by Mystification

According to Berger, oil paintings were mystified at the time they were created, and they continue to be mystified today. In both instances, they protect the economic and social order of capitalistic societies.

The rise of the oil painting coincided with the rise of the free art market in Europe. Almost all paintings during this time were done on commission, in large part because of the expense of the venture. The wealthier a person was, the more paintings he could commission. To have a house filled with commissioned paintings was a display of wealth and a point of pride. Because the paintings were commissioned, however, the patron had control over what the painting depicted.

Berger explains that this is a form of mystification, because if you study the paintings from this time period, you are not seeing a record of what was—you are seeing how the wealthiest class of people wanted to be portrayed. These depictions protected their social status, which is inherently connected to wealth, for all of history.

ARCHDUKE LEOPOLD WILHELM IN HIS PRIVATE PICTURE GALLERY BY TENIERS 1582-1649

(Shortform note: Berger explains how mystification benefits the wealthy, but he doesn’t provide a clear argument for how demystification of centuries-old paintings would affect modern-day capitalism. We might infer that if the masses were to understand the class stratification and oppression of the past, they might be more likely to recognize it in modern society and challenge its authority.)

Exercise: Breaking With the Tradition

Berger says that the vast majority of oil paintings from this time period fall into the norms of the tradition, but there are a minority that break the conventional rules and are exceptional. Test your eye and see if you can identify the paintings that agree or break with the tradition.

Examine the images below. In your opinion, do they follow the norms of the oil painting tradition or are they exceptional? Why or why not? (Remember, the norms of the tradition lie in the paintings’ subjects and values: displays of wealth, mythology, and so on.)

ADMIRAL DE RUYTER IN THE CASTLE OF ELMINA BY DE WITTE 1617-1692

LANDSCAPE IN FLANDERS BY RUBENS 1577-1640

Chapter 3: Nudity and Objectivity

Nude women were a prominent subject in European oil painting. Berger points out that in the same way oil paintings depicted wealth using images of land and objects, women were also seen as property to be flaunted.

Nudes, Berger says, are characterized by the objectification of the female “subject,” who through the assumed gaze of the male viewer is made into an object. Men who were wealthy or powerful enough to buy and commission oil paintings wanted nudes for the same reason they wanted oil paintings of valuable objects: to remind others and themselves that they were rich, powerful, and desirable.

Nude women in European oil paintings appear for the benefit and use of the assumed male viewer, who Berger calls the “spectator-owner.” He calls them this because the man who owns the painting “owns” the nude woman, and (in his mind) he’s also the reason why the nude woman is there—to display herself for him, the spectator.

RECLINING BACCHANTE BY TRUTAT 1824-1848

Berger notes that the nude woman is often being viewed by two or more men: A male within the painting, and the spectator-owner. Despite being desired by one or more men within the painting, the woman shows her loyalty to the spectator-owner through eye contact or by positioning her body to face him. Berger says that the owners of these paintings enjoyed and requested this because it made them feel dominant in an imaginary competition.

Look at how in the following examples, the nude woman is receiving attention within the painting, but her gaze and body language focus outward toward the spectator-owner:

ALLEGORY OF FORTUNE BY DOSSO DOSSI 1538

NELL GWYNNE BY LELY 1618-1680

SUSANNAH AND THE ELDERS BY TINTORETTO 1555-1556

Contemporary Nudes

According to Berger, the nudes of the oil painting tradition were highly focused on the spectator-owner and featured the male gaze within the paintings as well. Today’s nudes are less focused on being desirable, and more focused on breaking taboos. In many examples, the woman touches her own body and exudes a sexuality that up until recently was viewed as a character flaw. Since the “Me Too” movement of 2017, women have moved toward unapologetically embracing their sexuality and rebelling against the historical objectivity of their bodies.

Naked Versus Nude

Not all naked paintings are nudes. According to Berger, to be naked is to be yourself, and to be seen by others for who you are—it is vulnerability and honesty. To be nude, on the other hand, is to hide oneself and be seen by others as an object—usually for sexual fantasy. We can’t know for sure what the subject in an image is feeling, but Berger says there are three primary distinctions between nudes and nakedness that you can visually see in an image:

- The nude is conventionally attractive—the woman’s body is depicted in a way that satisfies man’s desire in a given time period. Nakedness will display “flaws” by conventional standards.

- The nude is present for the purpose of being viewed—she is visibly aware that she is the object of a man’s attention, evident by her eyeline and/or body positioning. Nakedness contains no exhibitionism or voyeurism. The woman is simply living her life as anyone would, which occasionally requires being naked.

- The nude is passive and still—often portrayed lying down in the supine position, the nude is inanimate, just as an object would be. Her face is placid or coy. Nakedness is portrayed using motion and expression—a towel slipping, a woman moving lustfully or appearing surprised, are examples that show that she’s a living human.

A central difference between nudes and naked paintings relates to Berger’s discussion of perspective. The “owner-spectator” of a nude is expected and entitled to be ogling at the woman, because she is his property. The viewer of a “naked” painting, on the other hand, is intrusive, or at the very least a surprise. The woman belongs to no one and isn’t posing for the viewer.

Consider the following examples of nude versus naked paintings:

Nude

ODALISQUE WITH SLAVE BY INGRES

The woman is lying in a supine position with her body presented to the spectator. The position is unnatural yet she is motionless like an object. Her facial expression is blank. Her skin and the contour of her body are flawless and statuesque.

VENUS AND THE LUTE PLAYER BY TITIAN 1565-70

The description of Odalisque With Slave can be directly applied here, with the addition of a male admirer to whom the woman pays no attention.

Naked

HELENE FOURMENT IN A FUR COAT BY RUBENS

The woman is looking at the spectator, but her body is not positioned as a presentation to him. She is covering herself as her towel slips, showing lifelike motion and modesty. Her facial expression is neither placid nor coy and could be interpreted as showing affection or familiarity. Her legs display realistic cellulite rather than the smoothness of a marble statue.

DANAE BY REMBRANDT 1606-1669

The motion and expression of this woman is enough to render it a naked painting and not a nude. Though her body faces the spectator, there is no indication that her attention is on him. She gestures to the side as if speaking to someone, something an object would not do. Her exposure appears to be an intrusion rather than an intentional display.

When speaking in terms of percentage, Berger explains that nudes are common in European oil paintings, and nakedness is rare. He infers that the rarity exists because the image of a naked woman that doesn’t “belong” to the spectator-owner is not marketable. Rather, these paintings were done by the painter not to present merchandise to a buyer, but to simply highlight the beauty of the naked form as well as the complexity of the woman. For these reasons, Berger says “naked” paintings should be considered exceptions to (not examples of) the European oil painting tradition.

(Shortform note: Sir Kenneth Clarke, Berger’s primary adversary, argues that to be naked is to be without clothes and to feel exposed or embarrassed because of it. It’s a vulnerable state of being. To be nude, he says, is intentional and comfortable. A nude represents a particular society’s ideal figure. This means that a nude in one country or one time period will be different than that of another.)

Mystification of the Nude

Now that Berger’s definition of a nude is firmly established, we can explore how this trend was and is mystified.

As Berger explains, the vast majority of paintings that depicted nudity were commissioned by wealthy men who wanted the illusion of owning the woman. The image was catered to his tastes in order to please him. This obscures the reality of what women actually looked like, how they behaved, and what their attitudes were toward their surroundings. What we are left with is not a record of how women were, but as of how the spectator-owners saw them, and how the painters depicted them.

By depicting women as a prize to be won, paintings from this time period oppressed women by creating competition among them and manipulating their perspective of their own gender. Berger explains that as long as women believe they belong to men, and that they must fit a conventional and submissive standard to be desirable, the men can maintain social, economic, and political control.

Filters: The Modern Mystification of Women

Berger notes that we don’t have an accurate idea of what women looked like during this time period because their image was manipulated and painted for the enjoyment of the male viewer. A similar phenomenon is taking place in social media in the 2020s—the use of filters.

Hundreds of filters exist that can be placed over photos and videos (even live) with one tap of the finger on a smartphone. Though all genders use filters, the primary users are female.

A filter is essentially a set of image manipulations that can be applied simultaneously and instantly. One moment you look like yourself, and in the next, you look like someone completely different. Their existence has changed beauty standards across the world and mystifies what women really look like. Just as we don’t have a clear understanding of what women looked like during the Renaissance, if someone 100 years from now looks back on photos from social media today, they too wouldn’t know how women of the 2020s truly looked. Rather, they will see the idealized image of the time, which is constantly in flux.

Exercise: Determine if Naked Is Nude

Berger uses set criteria to distinguish nudes from nakedness. Try out this particular way of seeing by analyzing 20th-century portraits using his methodology.

In each of these images, do you consider the subject to be nude or naked, according to Berger’s definitions? Why?

H.G. WITH STANDING NUDE BY MOSES SAWYER CIRCA 1950

RECLINING NUDE BY CRAIG NELSON CIRCA 1965

UNTITLED (NUDE FIGURE) BY VINCENT, LATE 20TH CENTURY

Chapter 4: The Impact of Reproduction

The invention of the camera (and therefore a means to reproduce images) forever changed how art was viewed, understood, and appreciated. Berger notes that for several hundred years, fine works of art were segregated from the working class, only to be enjoyed and understood by the wealthy elite. Now, for the first time in history, art could travel to the viewer, and the viewer could be anywhere in the world.

As one form of mystification lifted, room was made for a different sort—the intentional distortion of meaning through physical manipulation of the image. In this section, Berger lists all of the different ways someone can change the meaning of a work of art (intentionally or unintentionally) simply through the act of reproducing it.

Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Era of Mechanical Reproduction”

Berger notes that his discussion in this section draws heavily on philosopher Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Work of Art in the Era of Mechanical Reproduction.” Benjamin argued that reproduction of art devalues what he calls its “aura,” or its special, noble, meaning-giving power, which is present in the original work. Without connection to its physical place or the special moment-in-time quality of art that makes it timeless, art is open to political co-option.

Reproduction Removes the Art From Its Intended Home

Reproduction allows people from all over the world, from all backgrounds, to view paintings that they might otherwise never see. The vast majority of the world’s population hasn’t been to the Louvre in Paris, yet nearly everyone is familiar with the Mona Lisa, which resides there. In many ways, Berger says, this is a wonderful thing. It allows people from all economic situations to access art equally—in theory, that is.

The reality, Berger points out, is that the original meaning of a painting is distorted each time it’s viewed in a new location. Imagine that you’re viewing a painting of Jesus Christ on a crucifix. You’re standing in front of the original painting in a beautiful cathedral, surrounded by hushed whispers, ornate stained glass, and soaring ceilings. Now imagine you are looking at a replica of that same painting, and it’s hanging on the wall of your grandmother’s living room. It’s reasonable to assume that your reaction (and your interpretation of the work) would differ between the two experiences.

Before reproduction was available, Berger points out that paintings were usually commissioned with the location already in mind. The artist knew the setting in which the painting would be displayed, and he would use the information accordingly. The original intention of the artist is lost when a work of art is reproduced and displaced.

Smartphones and Place-Based Art

In 1600, you could only see a particular painting if you and that painting were in the same room. While that’s not exactly true for music, because different musicians could play the same song for different audiences, music was still singular in the sense that there was no way for you to hear a particular performance unless you were there while it was happening. The camera and recorded music made it possible for exponentially more people to see reproductions and hear recordings in exponentially more settings. The smartphone has done the same to an even greater degree.

While smartphones are undoubtedly a way art and music are divorced from place, some artists are using smartphones to create intentional place-based work. Using GPS, a Washington D.C. band created an album that you can only hear if you’re at the National Mall, listening on your phone. If you walk too far away from the Mall, the album won’t play.

Reproduction Breaks the Whole Into Parts

Before reproduction, paintings were only ever viewed and analyzed in their entirety. Even today, when you look at an original painting, your eye is likely to wander from one area to another; however, the entire work is in front of you—available for you to consider before deciding upon your interpretation.

After reproduction, paintings could be interpreted based on individual sections. Today, we interpret reproduced images in isolated sections all the time. Why the amputation? Why would someone display part of a painting rather than the whole thing? Berger explains the motivation: When a person has the freedom to pick and choose which sections of a painting to display, they gain control over the message that it sends.

A situation that occurs less often, but can be just as manipulative, is when paintings are displayed in video. The camera moves from one zoomed in portion of the painting to another until the whole painting has been shown. While on the surface this might seem the same as looking at the painting yourself, it isn’t. The choices that the cameraman makes, such as how long to linger over an image, or which order to display the images in, tells a story. He is in control of the narrative, not you.

In both of these cases, the viewer’s interpretation of the work is manipulated. As we’ll discuss in the next chapter, advertisers use this segmentation method frequently and skillfully—it’s a modern mystification of centuries-old art that supports capitalistic interests. As always, Berger encourages you to retain a skeptical eye and always ask yourself, “Who chose to display this image to me, and why?”

Cropping, Ethics, and the Media

Modern technology has made cropping photos easy and instant. Nearly every smartphone has a photo editing feature where you can separate an image into parts in the blink of an eye. It’s considered unethical for journalists to crop a photo if it’s going to change the meaning of the photo, but some news outlets engage in this behavior anyway.

In this thread, members of the public share examples of when the media has manipulated images to fit their narrative. One example of cropping shows former Vice President Pence and his wife walking at a nearly empty political rally. There are a few others walking alongside them, but the stands are empty. The next image shows the stands cropped out of the photo, which leaves the couple appearing to be in a crowd of people.

Reproduction Allows Proximity to Alter Meaning

Reproduction of an image allows people to place words or other images beside it, and proximity alone, Berger says, can alter the meaning of an image.

Proximity to Words

The content of the words placed beneath or beside an image isn’t as important as the way it changes how we interpret the image. Berger notes that when a piece of art stands alone, the viewer takes it in (along with the setting, as we discussed earlier in this chapter) and draws meaning. When words are present, however, that creative process is halted. Instead, the image becomes an illustration of the words.

For example, observe this painting by Titian with no context. Spend a few moments and try to make rudimentary sense of it:

Now, imagine that you saw this image reproduced in a magazine with the following words beneath it. Then study the image a second time.

Bacchus fights for his love, Ariadne, sacrificing human and animal lives in exchange for her devotion.

If you read the words before coming to your own understanding, your eyes will immediately search for visual information that supports the written meaning. (Shortform note: This caption was fabricated by us to illustrate Berger’s point. The image is titled: Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian 1520-1523.)

Shortform Commentary: Memes and the Power of Words

A modern-day example of words changing the meaning of an image can be found in memes. A meme is a digital image that is copied over and over with slight variations and passed along, usually for the sake of humor. Observe the “Disaster Girl” meme as an example of words changing the meaning of an image:

Proximity to Another Image

Just as words can alter the meaning of an image, two images placed side by side can have the same effect. Berger argues that what is seen immediately after an image, when there is no chance for digestion, changes its meaning. (Shortform note: This is another strategy often used by the media to convey a particular message. For example, a newspaper might print a photo of a protest directly next to a photo of a politician. This doesn’t mean the protest is about him, but that’s the meaning derived by their proximity.)

Using the Titian painting from the previous section, notice how the meaning of the painting shifts when it’s placed beside these two different contexts:

Reproduction Changes How We Value the Original Piece

Once works of art were able to be easily reproduced and disseminated, the images lost inherent value. They were too easy to come by. There was and still is, however, a great desire to see original works of art. Seeing a reproduction of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring isn’t particularly exciting, but most art lovers would be elated to stand before the original painting (currently located at Mauritshuis museum in the Netherlands). The interesting part is why…

According to Berger, the value of an original painting is now almost entirely due to its authenticity. That is, it’s valuable because it’s the original—not because it was a particularly skillful work, or because its meaning is profound. We stand in awe not because it was painted by our favorite artist, but because, “There’s the real one!”

Berger laments that modern visitors to museums often miss the point of the art entirely, and attend simply to be able to say they were in the presence of the Mona Lisa. Once again, he urges us to change our way of seeing.

Mona Lisa Voted Most Disappointing Tourist Attraction

In a 2019 poll, 2,000 Britons were asked what the most disappointing tourist attraction is. A whopping 86% of them chose the Mona Lisa. Often, a painting’s notoriety in itself creates an expectation of amazement or enlightenment. Museum-goers expect to step in front of a master work and gasp at the profound beauty. However, this is a recipe for disappointment. As Berger says, the value of paintings now largely rests in being an original, but this is a vacuous motivation for wanting to view a work of art.

Exercise: Manipulate Meaning Using Reproduction

In this chapter, we covered four ways that reproduction can be used to change the meaning of an image: removal from its original home, breaking the whole into parts, proximity to words, and proximity to another image. Test Berger’s theory by imagining how someone might manipulate an image.

Take a look at the image below. Using Berger’s theory, how could someone use words to manipulate the meaning of this image? Give an example.

Using the same painting above, describe another image that could be placed beside it that would affect its meaning. What new meaning would the side-by-side presentation give?

Chapter 5: Advertisements in the Modern Age